A Young Birder’s Take on Our Young Birders Event

Text and photos by Sayed Malawi, a high-school student and participant in this year's Young Birders Event August 15, 2012

A Great Horned Owl spotted during daylight was a highlight.

The group saw many breeding warblers, including this Chestnut-sided Warbler.

The weekend included tours and hands-on practice inside the Cornell Lab.

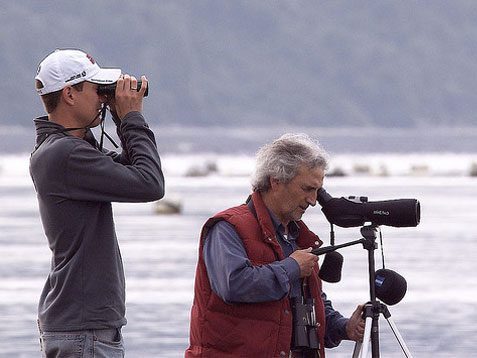

Standing at the edge of a scrubby patch of trees, Chris Wood was coaxing a rarity into view. The small bird, hidden by leaves and branches, chipped enthusiastically as it moved. Here and there I saw a leaf twitch or a twig shake as it made its way closer. Two adults and 10 teenagers waited, many of us hoping to get a glimpse of a life bird—a bird we’d never seen before.

Suddenly the Mourning Warbler appeared on an exposed log, offering a drop-dead look to myself and the other 11 people watching from just a few feet away. For a moment, it hesitated, as if it was so startled by the 12 humans that a few gray feathers had grown on its already silvery head. Then it was gone, chipping its way deeper into the brush.

The excitement of the moment took a little longer to dissipate. “That was my 350th,” said one teen from New Jersey. “As Mourning Warblers go, that was a really good look,” noted a more experienced birder from Connecticut. My own North America list isn’t quite at 350, but I was still happy with my lifer. After a little while we left the warbler in peace, and moved on.

It was an unusual occasion for an unusual bird. During the weekend of July 21, I traveled to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology with nine other aspiring young ornithologists hoping to learn how to take our interest in birds to the next level. I was taking part in the annual Young Birders Event, a weekend hosted by the Lab to expose a few lucky teens to a variety of careers involving birds. We were supervised each day by Chris Wood and Jessie Barry, Cornell Lab project leaders for eBird and the Merlin online identification project, respectively.

Birding with Chris and Jessie is something of a humbling experience. It’s not just that they can pick out a Canada Warbler chip note or a Pectoral Sandpiper several hundred yards away. The way that they are able to explain bird identification to those with much less experience is remarkable. I still don’t think I would be able to find that Pectoral, but I’m pretty sure I’d recognize it when someone else points one out. The highlight for me, though, wasn’t a warbler or a sandpiper; it was a Great Horned Owl seen in daylight. It appeared to have an injured eye, which turned its menacing blink into a charming wink.

Later the same day, we visited a special place to get even closer to a large variety of warblers: the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates, housed at the Cornell Lab. Led by Dr. Irby Lovette, director of the Lab’s Fuller Evolutionary Biology program, we explored Cornell’s specimen collection. We touched briefly on amphibians and fish, then made our way to the birds for an exercise in warbler phylogeny. Our goal was to organize a variety of warblers by placing them in groups on a phylogenetic tree, or putting them with their closest relatives. My group made a mistake with the American Redstart and Painted Redstart; despite their similar appearance, they are in fact not very closely related.

Nevertheless, I still feel pretty good about deducing that the Olive Warbler should come before the Yellow-breasted Chat on the evolutionary tree. Ornithologists are constantly revising our understanding of birds’ evolutionary relationships, and some of that work is done right here, in the Lab’s own PCR (polymerase chain reaction) lab. Here, Lab scientists analyze DNA in mediums like blood samples. Some of the discoveries made through this method lead to changes to the official American Ornithologists’ Union check-list, and eventually in the field guides we all carry. (One recent example is the removal of the beloved warbler genus Dendroica, which happened when those species were reclassified into Setophaga).

For some people, having the rare opportunity to explore the drawers in the bird collection was the highlight of the Night at the Museum. While I did have a good time roaming the collection (especially when I found a specimen of a Wallcreeper, a little-known creeperlike species I’ve always wanted to see—it makes its home on sheer cliffs at high elevations in Europe), I found the applications of the Lab’s collection even more interesting. In addition to the PCR lab, the Lab houses an ancient DNA laboratory, which can be used to analyze the genetic information from a tiny piece of a specimen, even ones that are centuries old.

More than anything else, I came away from the weekend with a broader view of what ornithology means today. The study of birds has evolved far beyond shooting specimens and even simply looking at them through a lens. Somehow, over the two days I spent at the Lab, I realized that a career with birds could mean studying them in the field, recording their sounds or images, building a computer program, or educating others. It’s comforting to be reminded that I’ll be able to learn about birds no matter which of these paths I choose.

For more information about the Young Birders Event, contact Jessie Barry at jb794@cornell.edu

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you