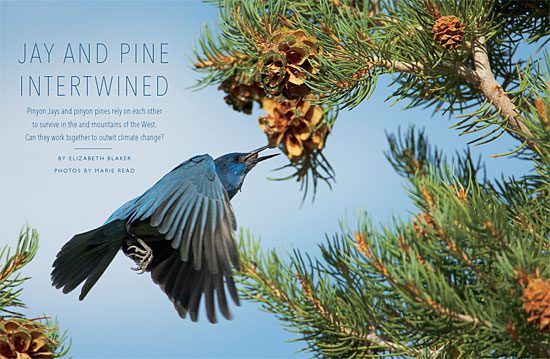

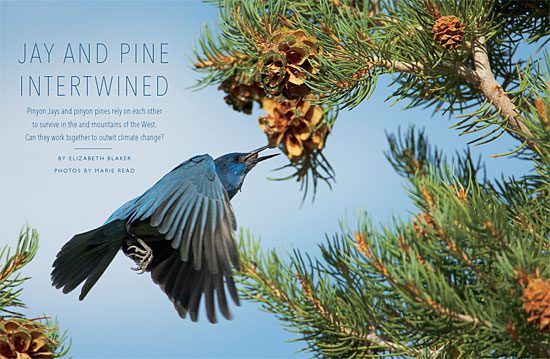

Jay and Pine Intertwined

By Elizabeth Blaker, Photos by Marie Read

October 15, 2012

Russ Benford felt bad about it, but trying to get mates to cheat on each other was part of his job as an ornithologist. Pinyon Jays are thought to be monogamous, as are humans, but are they any better at it than we are? To find out, Benford—a behavorial ecologist at Northern Arizona University—separated mated pairs of Pinyon Jays captured from forests in northern Arizona and placed them in aviaries with attractive members of the opposite sex. And he waited…

The cheating study is just one facet of research that Benford and other scientists across the western United States are exploring to learn more about Pinyon Jays. Much of the research these days focuses on how populations of these dusty-blue jays—a bit stouter than a scrub-jay, with a sharp beak adapted specifically for extracting seeds from the cones of pinyon pines—are faring as their favored habitat declines. After the U.S. Forest Service deemed pinyon-juniper woodlands to be of no commercial value, land managers from the 1940s to the 1960s set about trying to eradicate this habitat across the Southwest. Pinyon Jay populations plummeted.

The 21st century is setting up to be another tough time for pinyon pines, with frequent droughts and wildfires. Because of dwindling habitat, Pinyon Jays are classified as a species of concern by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

But Pinyon Jays are corvids, like crows and ravens, and therefore highly intelligent. And research has shown them to be highly adaptable to change. Although scientists are understandably alarmed by the species’ precipitous losses in numbers and habitat, they’re also cautiously optimistic. There’s reason to believe that Pinyon Jays may be smart enough to create a brighter future for themselves.

A Mutually Beneficial Relationship

The Pinyon Jay and pinyon pine share more than a name; their fates appear to be inextricably linked. The marriage of the Pinyon Jay to this tree has, over millennia, saved adult jays and their broods from starving during winter and early spring breeding seasons. In turn, the jays have helped disperse the seeds of pinyon pines. Eleven species of pinyon pines are found along with juniper trees in the vast woodlands of the semi-arid West. Most common are the two-needled pinyon and single-needled pinyon, which can hybridize with each other. Pinyons and junipers are usually short trees and sometimes twisted, with junipers more common at lower elevations and pinyon pines increasing in numbers at the upper reaches of the woodlands. Pinyon pine seeds are heavy and fat, rich in oils, and packed with protein and calories. They are too heavy to be dispersed by wind, so the pinyon tree needs animals to carry its seeds away from the parent tree and plant them.

That’s where Pinyon Jays come in. Some years pinyon pines produce bumper crops of seeds—so many seeds that even the greediest Pinyon Jay can’t eat them all. Because the seeds are available for only a couple of months, the jays cache seeds to eat later.

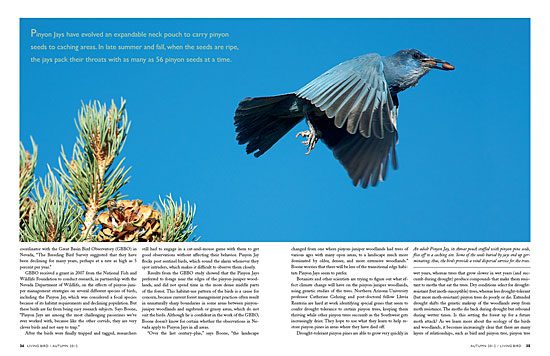

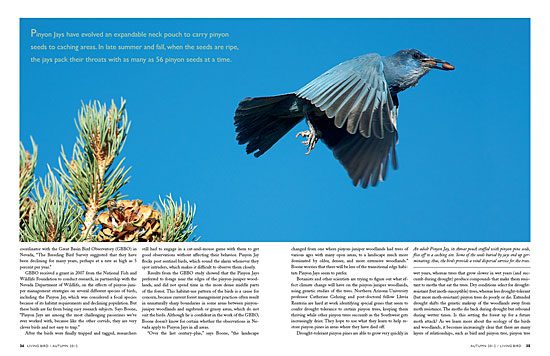

Pinyon Jays have evolved an expandable neck pouch to carry pinyon seeds to caching areas. In late summer and fall, when the seeds are ripe, the jays pack their throats with as many as 56 pinyon seeds at a time. When enough birds have full throats, flockmates shout rallying calls, and they fly off en masse to a treeless caching area, where they walk along shoulder to shoulder and poke the seeds into the ground like farmers sowing a crop. Benford’s experiments with captive Pinyon Jays indicate that they recall where they cached their seeds nearly 95 percent of the time. This leaves 5 percent of cached seeds in the soil where they have the potential to germinate—a win-win relationship for both bird and tree.

The relationship between Pinyon Jays and pinyon pines is so intimate, it even gets sexual. The mere sight of green pinyon cones stimulates reproduction in Pinyon Jays, according to research carried out near El Morro National Monument and other New Mexico sites in the 1960s and 1970s by University of New Mexico scientist J. D. Ligon. After seeing the green cones, male birds’ testicles increased in size and sperm production kicked in, and in females ovary development was stimulated. In years with few cones, Ligon found that the New Mexico Pinyon Jays sometimes didn’t breed at all. By examining the stomach contents of the birds, Ligon learned that when the pinyon seed crop is poor, Pinyon Jays resort to eating less-nutritous ponderosa pine seeds and juniper berries, but during these seed-poor years most chicks don’t survive to adulthood.

Dwindling Trees, Declining Birds

Unfortunately, the early stages of global climate change already appear to be causing die-offs of pinyon trees in the West. Meanwhile, Pinyon Jays are declining in numbers, and biologists fear that the relationship with the trees that has sustained the jays, and shaped the habits of both the tree and the bird, may now lead to the Pinyon Jays’ downfall. According to John Boone, research coordinator with the Great Basin Bird Observatory (GBBO) in Nevada, “The Breeding Bird Survey suggested that they have been declining for many years, perhaps at a rate as high as 5 percent per year.”

GBBO received a grant in 2007 from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to conduct research, in partnership with the Nevada Department of Wildlife, on the effects of pinyon-juniper management strategies on several different species of birds, including the Pinyon Jay, which was considered a focal species because of its habitat requirements and declining population. But these birds are far from being easy research subjects. Says Boone, “Pinyon Jays are among the most challenging passerines we’ve ever worked with, because like the other corvids, they are very clever birds and not easy to trap.”

After the birds were finally trapped and tagged, researchers still had to engage in a cat-and-mouse game with them to get good observations without affecting their behavior. Pinyon Jay flocks post sentinel birds, which sound the alarm whenever they spot intruders, which makes it difficult to observe them closely.

Results from the GBBO study showed that the Pinyon Jays preferred to forage near the edges of the pinyon-juniper woodlands, and did not spend time in the more dense middle parts of the forest. This habitat-use pattern of the birds is a cause for concern, because current forest management practices often result in unnaturally sharp boundaries in some areas between pinyon-juniper woodlands and sagebrush or grassy areas, which do not suit the birds. Although he is confident in the work of the GBBO, Boone doesn’t know for certain whether the observations in Nevada apply to Pinyon Jays in all areas.

“Over the last century-plus,” says Boone, “the landscape changed from one where pinyon-juniper woodlands had trees of various ages with many open areas, to a landscape much more dominated by older, denser, and more extensive woodlands.” Boone worries that there will be less of the transitional edge habitats Pinyon Jays seem to prefer.

Botanists and other scientists are trying to figure out what effect climate change will have on the pinyon-juniper woodlands, using genetic studies of the trees. Northern Arizona University professor Catherine Gehring and post-doctoral fellow Lluvia Renteria are hard at work identifying special genes that seem to confer drought tolerance to certain pinyon trees, keeping them thriving while other pinyon trees succumb as the Southwest gets increasingly drier. They hope to use what they learn to help restore pinyon pines in areas where they have died off.

Drought-tolerant pinyon pines are able to grow very quickly in wet years, whereas trees that grow slower in wet years (and succumb during drought) produce compounds that make them resistant to moths that eat the trees. Dry conditions select for drought-resistant (but moth-susceptible) trees, whereas less drought-tolerant (but more moth-resistant) pinyon trees do poorly or die. Extended drought shifts the genetic makeup of the woodlands away from moth resistance. The moths die back during drought but rebound during wetter times. Is this setting the forest up for a future moth attack? As we learn more about the ecology of the birds and woodlands, it becomes increasingly clear that there are many layers of relationships, such as bird and pinyon tree, pinyon tree and moth, and climate and pinyon tree, continuing down to the important communities of beneficial fungi and microbes that live in the soil at the trees’ roots.

A record dry winter and spring in 2002 to 2003 killed many of the Flagstaff-area Pinyon Jays, which Benford had been studying for years. Years of careful bird measurements taken by Benford and his predecessors Russ Balda, Gary Bateman, and John Marzluff allowed Benford to observe evolution in action. Birds that were a little heavier survived better than those that were slightly lighter. Pinyon Jays living in the area are now a bit bigger on average than they were prior to that drought. Male Pinyon Jays tend to be slightly heavier than females. Because of this, many females of mated pairs died, leaving widowed males. As Benford discovered during his “cheating spouse” experiment, Pinyon Jays are monogamous. He simply could not get them to cheat on each other, unlike other bird species he tested. The drought disrupted the social structure of the flock, but the birds adjusted by seeking new mates in other flocks or helping at the nests of their parents rather than raising their own broods.

Climatologists have suggested that global climate change may result in a period of chaotic weather patterns. The pinyon-juniper woodlands may be able to respond to some of these changes. Jacob Gibson, a Utah State University graduate student researcher who studies pinyon-juniper woodlands at the landscape scale, offers this hopeful observation: “There are many intricate ways with which distribution [of the pinyon trees] may persist where climatic conditions are becoming unfavorable.” Evidence from ancient packrat mounds reveals that pinyon-juniper woodlands have been moving north and south, and up and down elevation gradients, and more quickly than they could do without help. It is likely that the Pinyon Jays have helped the trees survive climate changes for thousands of years. Though the trees and birds are able to respond to periodic changes, global climate change may present the tree and the birds with a magnitude of change that outstrips their prodigious ability to adapt.

Fire is another problem that the Pinyon Jays must face, because fires are now sweeping through the West on an epic scale due to years of fire suppression. During the summer of 2010, Benford watched a wildfire destroy the breeding grounds of one of his Flagstaff, Arizona, study flocks. Pinyon Jays have home territories that they inhabit year after year. As the breeding grounds of the flock burned, Benford said, “I saw bird after bird, group after group, leaving their territory, which they would never normally do, and as they were flying, adult birds were giving juvenile begging calls.”

Pinyon Jays adapt physically and socially to short-term drought and to fire, and they can live, apparently quite well, in the midst of human housing developments—as long as they have stands of trees for roosting, pinyon seeds to eat, and large open areas nearby for caching.

“To conserve the species and improve its prognosis,” says Benford, “I think intelligent regional resource management plans should be developed, plans that include the widespread preservation of pinyon-juniper woodland and open areas.”

The future of the Pinyon Jay and its special woodlands is unclear. What is clear is that both the trees of the woodland and the Pinyon Jays are resourceful. Research is revealing a complex interplay among tree, bird, climate, and insects, a twisting, spiraling kind of dance.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you