Book Review: Gifts of the Crow, by John Marzluff and Tony Angell

Reviewed by Stephen J. Bodio

January 15, 2013

Many if not most books about birds deal with their appearance. This quarter, two very different books (Gifts of the Crow and Nature’s Compass) explore the less visible aspects of birds, although one is also a visual delight.

Gifts of the Crow records the further explorations of the award-winning team of John Marzluff and Tony Angell, and takes us deeper into what Bernd Heinrich called “the mind of the raven.” The authors state their thesis up front: “These animals are exceptionally smart…they use their wisdom to infer, discriminate, test, learn, remember, foresee, mourn, warn of impending doom, recognize people, seek revenge, lure or stampede other birds to their death, quaff coffee and beer, turn on lights to stay warm or expose danger, speak, steal, deceive, gift, windsurf, play with cats, and team up to satisfy their appetite for diverse foods, whether soft cheese from a can or a meal of dead seal.”

It is a strong statement considering that most people, even the scientifically sophisticated, tend to think of birds as more hard-wired and instinctual than mammals. But Marzluff and Angell make their case with ease, beginning with a description of how Betty, a New Caledonian Crow, fashions a wire hook to fish a piece of food out of a cylinder where she can see it but not touch it. As they explain, “this ingenuity—crafting a hook from a foreign material and using it to gain an unreachable reward in a new setting—requires, thinking, appraisal, and planning.”

The authors do not rely merely on anecdotes, though they tell good stories. The “Birdbrains” chapter analyzes the neurology and evolution of brain power, and there is a detailed chapter on the nature of language. They then examine “delinquency,” insight, play, emotion, and self-awareness, demonstrating that crows are capable of all. Marzluff and Angell provide examples ranging from the humorous to the poignant to the startling: “The engine of innovation is the willingness to try something new. Sometimes this can lead crows to smoke and drink.” Play can lead to what the authors call “delinquency”; I have seen a magpie, a close relative, pull a dog’s tail to distract him while another steals his food. As they entertain you with such anecdotes, they simultaneously educate the reader about tougher concepts: neurons, brain physiology, dopamine.

For example, they explain the neurochemistry of stress: “during stressful situations, opioid release is suppressed, and the influence of norepinephrine on neurons in the amygdala is less constrained so that more, and possibly different, connections can be made between the amygdala and other brain regions.” And how this becomes sadness: “We are convinced that crows and ravens gather around their dead because it is important to their own survival that they learn the causes and consequences of another crow’s death. We also suspect that mates and relatives mourn their loss.”

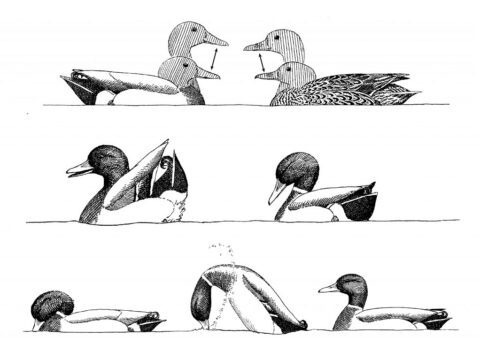

Angell’s illustrations are an integral part of the work, ranging from whimsical to straightforwardly scientific (an appendix of supplemental images makes brain structure clear). Given a choice of what to hang on my wall, I would pick the whimsical. Consider a worried-looking Charles Dickens “consulting” his raven at his desk; the crow lecturing dogs on the campus at Missoula; the cheerfully gruesome Tasmanian Raven on a roadkill “devil”; the crow rotating his head to puzzle out the details of a researcher’s upside-down mask.

We seem to be entering (or re-entering) a world where animals can be seen as complex beings. As the authors put it: “Our realization that the nature that we often take for granted includes animals that think and dream, fight and play, reason and take risks, emote and intuit, may be the greatest modern gift of the crow.”

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you