Searching for The Endemic Birds of Socotra Island, Yemen

By Mel White

April 15, 2013

The taxi driver speaks little English and I speak no Arabic, but he seems eager to talk as we rumble through the ancient streets of Sana’a. I imagine he doesn’t get many American passengers.

We’re heading for the airport, so the conversation starter is obvious: “Where are you going this morning?” he asks.

“To Socotra,” I say, wondering if he knows where it is.

“Ah, Socotra!” he says, and even in the predawn darkness I can see his big smile. He takes both hands off the wheel to give me two thumbs up. “Yemen,” he says, holding his left hand out to the side. “Socotra,” he says, stretching his right hand opposite.

“Different?”

“Very different,” the cabbie says. “Very peaceful, very beautiful.”

A few hours later, the Yemenia Airways 737 banks over the Arabian Sea, and I get a look at my island destination. Craggy cliffs rise along its western end, and long beaches of pale-yellow sand line much of the northern shore. Seasonal streams, known as “wadis” in Arabia, trace green paths through the scrubland. If from the air I can’t yet appreciate Socotra’s beauty, I can see that it’s as rugged and unpopulated as I’d read.

It’s not scenery that’s brought me here, though. This island off the Horn of Africa, just 80 miles long by 25 miles wide, ranks among the world’s top centers of endemism. No matter where you stand, from sea level to nearly a mile high in the central Hajhir Mountains, you’re within sight of something found nowhere else on earth.

Socotra is best known for some extremely odd plants, including the desert rose and the cucumber tree—the only tree in the gourd family—and for endemism that tops 30 percent for plants and lepidoptera, 90 percent for reptiles, 95 percent for land snails, and 100 percent for cave crustaceans. The island also hosts seven endemic birds, which I’m hoping to encounter as I roam its hinterlands.

Socotra’s small airport was built in 1999; before then, the only access to the island was by boat. Violent monsoon winds prevent sea landings for several months of the year—one factor contributing to Socotra’s centuries-long isolation. Another is that there’s simply nothing here that anyone cares about: no oil, no minerals, no timber or other resources to exploit—just 45,000 people who live by raising goats, fishing, and harvesting dates, and who speak an unwritten language that predates Arabic and is understood by only a handful of people off the island.

I’m met at the airport by Kay Van Damme, a Belgian biologist who’s been visiting Socotra annually for more than a decade and who’s become a dedicated advocate for the preservation of both the island’s ecosystems and its culture. After a brief period of scientific interest in Socotra in the late 19th century, the island was fairly well ignored until the airport improved access. Kay is one of several biologists who have renewed study of Socotra. He remembers that on his first visit in 1999, he and his companions were discovering new species daily by exploring caves, wading creeks, and even by simply walking the trails.

The winding road from the airport to the dusty capital city of Hadibu hugs the hilly coast, along the dazzlingly intense blue-green sea. At my hotel I’m greeted by dozens of one of Socotra’s special (though not endemic) birds, staring down at me from perches on walls and roofs. Egyptian Vultures have been in serious decline across much of their range—the population has fallen more than 50 percent in Europe and Africa, and even more in India—yet on Socotra they’re so common and unafraid that many visitors think these shaggy whitish birds are some kind of odd chicken. To appreciate them esthetically it’s best not to think about their dietary habits, since the yellow color of their bare facial skin is thought to result from eating feces. There are hundreds of Egyptian Vultures on Socotra, and their faces are very colorful.

Our party, including my excellent and entertaining driver-guide Ismael Mohammed Ahmed Socotri, immediately sets out for the Homhil Protected Area near the island’s eastern tip. The road, at first new and paved, soon becomes a dirt track as we pass through arid croton and jatropha scrubland, brightened here and there by the fuchsia flowers of the desert rose. Its blooms top a weirdly squat trunk, misshapen like something from a Salvador Dalí painting. (The species nameobesum is entirely accurate.) We climb to a limestone plateau dotted with dragon’s blood, the otherworldly tree that’s become the botanical symbol of Socotra, and frankincense, the tree whose aromatic dried sap was once as valuable as gold.

At a reservoir we pause to enjoy a small flock of Greater Flamingos, and I learn to my delight that Ismael is a birder himself. Not only does he know where to look for some of the island’s special species, he understands when I call out for him to stop so I can ogle a dickeybird in a roadside shrub.

Common Socotra birds new to me include Desert Wheatear, Black-crowned Sparrow-Lark, the very attractive Cinnamon-breasted Bunting, and the glossy-black, long-tailed Somali Starling. My first Socotra endemic is, not surprisingly, the most common of the island specialties: Socotra Sparrow, a Passer that flocks and chatters and looks like a House Sparrow, though it has more chestnut in its plumage.

The next day we hike into the Hajhir Mountains, and along the way Kay Van Damme tells me that the rugged granite spires towering above us are the result of three different periods of volcanism dating back 600 million years.

“This area we’re entering now has the highest density of endemic plants in the whole of Asia,” he says. Once part of the Gondwana supercontinent with Africa and India, Socotra was still connected to Africa and Arabia about 35 million years ago. Today it maintains flora and fauna with elements of Europe, Africa, and Asia. “As Arabia and Africa got drier, Socotra stayed green because it’s an island, and because of the monsoon,” Kay says. “Its diverse habitats acted as refugia for many species.” Over the past 20 million years Socotra has been joined by a land bridge to Africa at times of low sea levels, allowing species to move back and forth; at other times the sea covered most of the island except for the high Hajhir peaks, creating isolation and speciation.

A small bird with a decurved beak, probing flowers, becomes my second endemic: Socotra Sunbird. It lacks the iridescent colors of many of its relatives in theNectariniidae and proves to be fairly common throughout the island. It’s an important pollinator for Socotra flora, including a few of the endemic plants. We stop at a wadi for lunch and a third endemic arrives. Two Socotra Starlings hop around the streamside rocks, looking much like the Somali Starling, though with a shorter tail and different female plumage. Both shiny-black species show reddish wing patches in flight. Farther along the trail we spot birds representing resident subspecies of more widely distributed species: Long-billed Pipit, Southern Gray Shrike, and White-breasted White-eye.

The scenery gets even more spectacular as we ascend, with cliffs and eroded peaks looming higher and higher, until we arrive at the tiny village where we’re to spend the night. Thavahinitin, it’s called, or “place of small flat rocks”—a name that seems inadequate for one of the most beautiful landscapes I’ve ever seen.

The day’s blue sky darkens in the afternoon as clouds lower to obscure the mountaintops. This is Socotra’s famous “mist,” or heavy fog, which settles in nightly and nourishes rare and endemic plants in the highlands. Unfortunately, some of these are targets for collectors, who visit Socotra and smuggle out plants (and spiders and lizards and other species) for sale in Europe. Botanist Lisa Banfield, accompanying us to Thavahinitin, climbs a nearby hill to check on an ultra-rare succulent of the monotypic genus Duvalliandra, known to occur only within a half-mile or so of the village. She’s dismayed to discover several clumps missing, obviously dug up and removed by collectors.

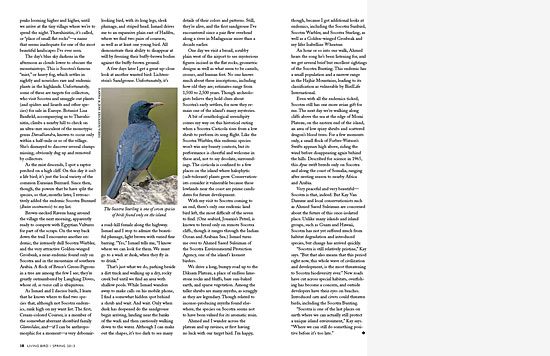

As the mist descends, I spot a raptor perched on a high cliff. On this day it isn’t a life bird; it’s just the local variety of the common Eurasian Buzzard. Since then, though, the powers that be have split the species, so that, months later, I retroactively added the endemic Socotra Buzzard (Buteo socotraensis) to my list.

Brown-necked Ravens hang around the village the next morning, apparently ready to compete with Egyptian Vultures for part of the scraps. On the way back down the trail I encounter another endemic, the intensely dull Socotra Warbler, and the very attractive Golden-winged Grosbeak, a near-endemic found only on Socotra and in the mountains of southern Arabia. A flock of Bruce’s Green-Pigeons in a tree are among the few I see; they’re greatly outnumbered by Laughing Doves, whose oh, so rococo call is ubiquitous.

As Ismael and I discuss birds, I learn that he knows where to find two species that, although not Socotra endemics, rank high on my want list. The first, Cream-colored Courser, is a member of the somewhat aberrant shorebird familyGlareolidae, and—if I can be anthropomorphic for a moment—a very debonair-looking bird, with its long legs, sleek plumage, and striped head. Ismael drives me to an expansive plain east of Hadibu, where we find two pairs of coursers, as well as at least one young bird. All demonstrate their ability to disappear at will by freezing their buffy-brown bodies against the buffy-brown ground.

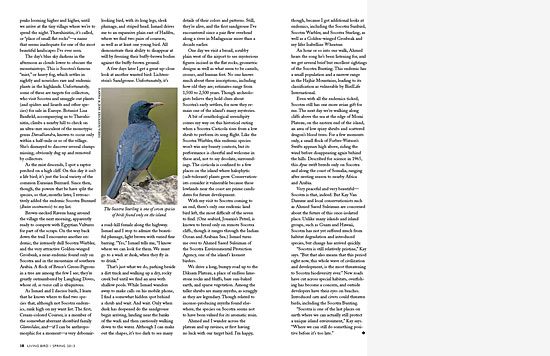

A few days later I get a great up-close look at another wanted bird: Lichtenstein’s Sandgrouse. Unfortunately, it’s a road-kill female along the highway. Ismael and I stop to admire the beautiful plumage, light brown with varied fine barring. “Yes,” Ismael tells me, “I know where we can look for them. We must go to a wadi at dusk, when they fly in to drink.”

That’s just what we do, parking beside a dirt track and walking up a dry, rocky creek bed until we find an area with shallow pools. While Ismael wanders away to make calls on his mobile phone, I find a somewhat hidden spot behind a shrub and wait. And wait. Only when dusk has deepened do the sandgrouse begin arriving, landing near the banks of the wadi and then cautiously walking down to the water. Although I can make out the shapes, it’s too dark to see many details of their colors and patterns. Still, they’re alive, and the first sandgrouse I’ve encountered since a pair flew overhead along a river in Madagascar more than a decade earlier.

One day we visit a broad, scrubby plain west of the airport to see mysterious figures incised in the flat rocks, geometric designs as well as what seem to be camels, crosses, and human feet. No one knows much about these inscriptions, including how old they are; estimates range from 1,500 to 2,500 years. Though archeologists believe they hold clues about Socotra’s early settlers, for now they remain one of the island’s many mysteries.

A bit of ornithological serendipity comes my way on this historical outing when a Socotra Cisticola rises from a low shrub to perform its song flight. Like the Socotra Warbler, this endemic species won’t win any beauty contests, but its performance is cheerful and welcome in these arid, not to say desolate, surroundings. The cisticola is confined to a few places on the island where halophytic (salt-tolerant) plants grow. Conservationists consider it vulnerable because these lowlands near the coast are prime candidates for future development.

With my visit to Socotra coming to an end, there’s only one endemic land bird left, the most difficult of the seven to find. (One seabird, Jouanin’s Petrel, is known to breed only on remote Socotra cliffs, though it ranges through the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea.) Ismael turns me over to Ahmed Saeed Suleiman of the Socotra Environmental Protection Agency, one of the island’s keenest birders.

We drive a long, bumpy road up to the Diksam Plateau, a place of endless limestone rocks and bluffs, bare sun-baked earth, and sparse vegetation. Among the taller shrubs are many myrrhs, as scraggly as they are legendary. Though related to incense-producing myrrhs found elsewhere, the species on Socotra seems not to have been valued for its aromatic resin.

Ahmed and I wander across the plateau and up ravines, at first having no luck with our target bird. I’m happy, though, because I get additional looks at endemics, including the Socotra Sunbird, Socotra Warbler, and Socotra Starling, as well as a Golden-winged Grosbeak and my lifer Isabelline Wheatear.

An hour or so into our walk, Ahmed hears the song he’s been listening for, and we get several brief but excellent sightings of the Socotra Bunting. This endemic has a small population and a narrow range in the Hajhir Mountains, leading to its classification as vulnerable by BirdLife International.

Even with all the endemics ticked, Socotra still has one more avian gift for me. The next day we’re walking along cliffs above the sea at the edge of Momi Plateau, on the eastern end of the island, an area of low spiny shrubs and scattered dragon’s blood trees. For a few moments only, a small flock of Forbes-Watson’s Swifts appears high above, riding the wind before disappearing again behind the hills. Described for science in 1965, this Apus swift breeds only on Socotra and along the coast of Somalia, ranging after nesting season to nearby Africa and Arabia.

Very peaceful and very beautiful— Socotra is that, indeed. But Kay Van Damme and local conservationists such as Ahmed Saeed Suleiman are concerned about the future of this once-isolated place. Unlike many islands and island groups, such as Guam and Hawaii, Socotra has not yet suffered much from habitat degradation and introduced species, but change has arrived quickly.

“Socotra is still relatively pristine,” Kay says. “But that also means that this period right now, this whole wave of civilization and development, is the most threatening to Socotra biodiversity ever.” New roads have cut across special habitats, overfishing has become a concern, and outside developers have their eyes on beaches. Introduced cats and civets could threaten birds, including the Socotra Bunting.

“Socotra is one of the last places on earth where we can actually still protect a unique island environment,” Kay says. “Where we can still do something positive before it’s too late.”

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you