Western Bluebirds Sing Like Their Neighbors, Not Necessarily Like Their Family

By Pat Leonard October 13, 2014

If you have an ear for dialects, you can probably take a good guess as to a person’s origins. The same words spoken by people raised in Brooklyn, Boston, and Bakersfield tend to sound different (though still recognizable). The tone and pitch of words are often influenced by the sounds heard and learned from within each individual’s neighborhood and family.

Family and neighbors also play a key role in the songs sung by Western Bluebirds, according to a two-year study published in the journal Animal Behaviour. Conducted at the Hastings Natural History Reservation in Carmel Valley, California, the study found that Western Bluebirds not only share their songs with relatives but with unrelated bluebirds that live nearby—i.e., the neighbors.

The researchers found that, no matter where they were raised, when male Western Bluebirds move to their own territories they share songs with their closest neighbors. That’s true whether the other birds are related or not, though they do a bit more sharing with nearby relatives. On the flip side, they rarely share notes with non-neighboring birds, even if they are related.

“It’s like speaking the dialect of the neighborhood you move into,” says study author Çağlar Akçay who led the research during his postdoctoral work at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “We wanted to find out if the birds learn from and share songs only with relatives—in which case the songs would function as a way to identify family—a ‘family signature.’ But if they learned and shared songs with nonrelatives too, then the songs could not stand alone as a means of recognizing kin.”

As a cooperatively breeding species, it’s important for a Western Bluebird to recognize close family. Male Western Bluebirds tend to breed next door to their parents, brothers, and sometimes grandparents, often sharing a boundary with a male relative’s territory. If dispersed males are unable to breed on their own, they will help raise the young in the nest of their parents, a parent and step-parent, a brother, or even a grandfather. Western Bluebird territories are variable but the longest song-sharing distance measured to date at the Hastings Reservation is 2.2 miles (3.6 km). A maximum sharing distance has not been determined.

Though females of the species also sing, they disperse farther away and only one-fifth as many stay in the study area. Also, females don’t sing during the pre-dawn chorus, and consequently they are harder to record. For these reasons, female Western Bluebirds were not part of this study.

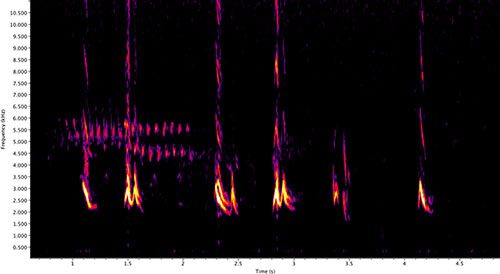

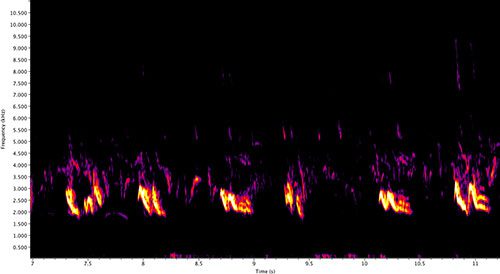

Male Western Bluebird songs were recorded for the study during the song-filled early dawn. Because the human ear isn’t up to the job when it comes to noting the subtle differences among the bluebird songs, the recordings were processed through sound analysis software to produce images, or spectrograms, of each note. Three independent judges compared spectrograms visually and agreed 98% of the time on which songs were shared and which were not. (More on how to read spectrograms.)

“On average, Western Bluebirds have eight or nine ways of making their pew sound and a couple variations for their chuck notes,” Akçay says. “These are the building blocks of their song.”

Akçay says it is the “acoustic signature” of each note type that matters for identification—meaning how the sound frequency is modulated. One note might have a very steep increase in frequency while another might be more gradual.

It’s not clear what advantage, if any, the bluebirds might gain by sharing songs with nonrelatives but Akçay says a number of theories could be investigated. Studies of other bird species have suggested that shared songs can be used to signal aggression between males, to indicate a male’s fitness for breeding, or as a way to reduce or avoid aggression among birds that are known to each other.

So what happens if a bluebird changes its territory or its neighbors change when new birds move in next door? Preliminary findings suggest the birds don’t completely change their repertoire but they do change.

“We actually had one individual that made a really big move from one year to the next,” Akçay says. “We had recordings of him both years and he kept 80 percent of his songs after the move. The other 20 percent were new songs adopted after the move.”

Akçay concludes, “The major takeaway here is that Western Bluebirds probably identify kin in a linear process—first noting through song that the other bird is a specific individual such as ‘Joe,’ or ‘Fred,’ then further noting, ‘Joe is my brother’ or ‘it’s Fred the neighbor who is not related.’ This second stage of classification may be helped by other cues such as behavior, appearance, and even smell in addition to shared song.”

The study is part of a 30-year research program conducted at Hastings Reservation by Janis Dickinson, who directs the Cornell Lab’s Citizen Science program and is a Cornell University professor. This long-term study, funded in part by the National Science Foundation, has provided a wealth of knowledge about social behavior on a large sample of birds with known social relationships, making these kinds of discoveries possible.

The study, Song sharing with neighbors and relatives in a cooperatively breeding songbird, was coauthored by Akçay and Dickinson with students Katherine L. Hambury (Cornell Lab), J. Andrew Arnold (Cornell Lab and Old Dominion University), Alison M. Nevins (Cornell Lab), all of whom contributed to recording, field experiments, and classification of vocalizations.

More about bird song:

- All About Bird Song is a free, seven-part interactive resource from the Cornell Lab

- Bird ID Skills: Songs & Calls contains a section on how to read spectrograms

- Bird Song Hero challenges you to recognize a bird’s song by its spectrogram

- Our Review: Best iPhone Apps for Learning Bird Songs

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you