Moneyball for Shorebirds: How Precision Analytics Are Changing Habitat Conservation

By Gustave Axelson

From the Autumn 2014 issue of Living Bird magazine.

Long-billed Dowitcher by Brian Sullivan October 31, 2014Two rice fields in California’s Central Valley—one so dry, the parched ground was cracked in patterns like a shattered windshield. On the other, a couple inches of still water was disturbed by the march of Long-billed Dowitchers, rhythmically pumping and probing like an advancing army of sewing machines.

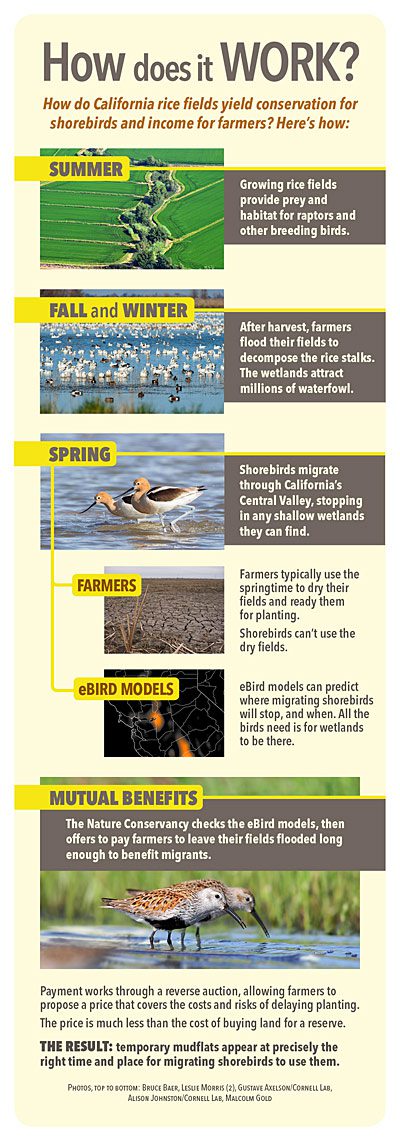

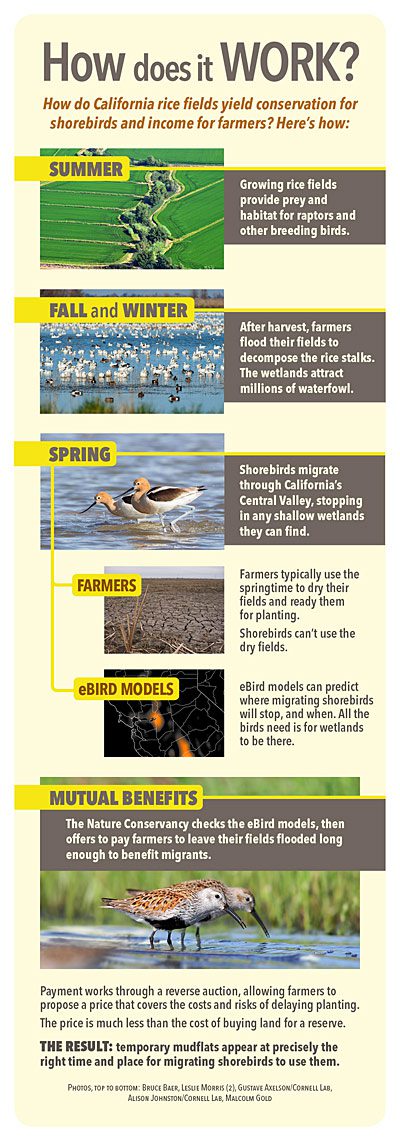

The dry field is what most of the 500,000 acres of rice country in between the Sierra Nevada and the Coast Range looks like in late winter, as farmers dry out their beds to prepare for seeding in spring. The latter is what just 2 percent of the Central Valley’s rice fields looked like last February, an anomaly holding 2 to 4 inches of water. But it was no accident. The farmer was paid to put the water there, in a wager that the birds would come. And eBirders helped place the bet.

In the midst of an epic drought in California, the worst in decades, rice farmer Amelia Harter flooded 170 acres—more than two-thirds of her farm—with a few inches of water, and in the process provided an oasis for these dowitchers and the other 24 species of shorebirds that make great intercontinental voyages along the Pacific Flyway. Before the California Gold Rush of 1849, this valley was all soggy with rivers, creeks, and sloughs that hosted birds by the tens of millions. Now more than 95 percent of the Central Valley’s natural wetlands have been lost. Rice fields represent the next-best surrogate habitat. During duck migration in fall and winter, these rice fields host more than 7 million waterfowl, one of the highest densities anywhere on earth.

Rice fields in California’s Central Valley are drained after harvest in the winter. During the epic drought, more of these rice fields are being left dry throughout the year.

The Nature Conservancy is paying rice farmers to keep water on some rice fields to create much-needed habitat for migratory shorebirds.

But by the end of January, duck-hunting season is over in California, and most farmers pull the plug and dry out their fields. That’s bad news for shorebirds, because their migration peaks from February into spring. Many shorebird species are of conservation concern and appear on the latest State of the Birds Watch List.

“When you look at the eBird maps, there’s clearly a mismatch,” said TNC California scientist Mark Reynolds. “There’s a lot of shorebird occurrence throughout the valley, but then the satellite imagery shows there’s not a lot of water availability on the ground.”

Last winter Reynolds and TNC California launched a first-of-its-kind conservation partnership with Cornell Lab of Ornithology information science director Steve Kelling and the eBird program to rectify that mismatch. The project combined precision big-data analytics from eBird—fueled by the more than 230,000 birder checklists submitted to eBird from California—with NASA satellite technology and a market-based mechanism to pay farmers to provide shorebird habitat, developed by TNC economists.

That’s how Harter came to flood her fields for the month of February, as part of a temporary contract with TNC California. “I always see bird watchers driving up and down the roads by the rice fields, looking at cranes and such,” she said. “We’ve always known our farm was good for birds.”

Harter was one of 40 rice farmers enrolled in the pilot program, called BirdReturns. More than 10,000 acres of rice fields were flooded in 4-, 6-, and 8-week contracts. It’s part of an emerging discipline in ecological science called dynamic conservation, where habitat is created over shifting periods of time and ranges of places to meet the changing needs of migratory wildlife. TNC called their flooded fields “pop-up wetlands,” like the trendy ephemeral restaurants that set the culinary scene abuzz.

“If I go to visit a city on vacation, I don’t want to buy a house. I want to find a hotel room,” explained TNC economist Eric Hallstein. “It’s the same thing here. We want to temporarily rent out habitat for these shorebirds, for just a few weeks of the year, when they’re passing through.”

The pop-ups produced some eye-popping results in their first year—surveys on the BirdReturns fields showed more than 220,000 birds representing 57 species, including every migratory shorebird species in the Central Valley. Recorded shorebird densities averaged well over 100 birds per acre in March, 10 times the number of shorebirds found in other areas outside the project.

A Good Deal for Farmers

Doug Thomas is mighty proud of his family farm at the doorstep of the Sutter Buttes. He watched the day’s first rays of sun bounce off the buttes as he gazed across the glistening water on his rice fields and reflected on how his family makes a living.

“A little bit of water goes a long way for shorebirds,” said the TNC’s Reynolds.

“We grow a crop that feeds people from the Pacific Rim to right here at home,” Thomas said, his hands tucked into the pockets of his Carhartt jacket. “If you eat a sushi roll in the United States, you’re most likely eating California rice.” (Buying California rice is one way to support bird-friendly habitat in the United States.)

When a Long-billed Curlew glided overhead, Thomas stopped midsentence to watch. Birds were a big reason he got into rice farming.

An Iraq war vet, Thomas served a tour of duty and then attended the University of California at Davis to earn a master’s degree in avian ecology. He was all set for a career as a waterfowl biologist, but when he and his wife had twins, he suddenly found himself looking for an immediate way to support his new family. His in-laws owned a rice-farming operation and offered Thomas and his wife an opportunity to join the family business.

“The way I looked at it, this was a way to manage 3,000 acres of wetland habitat exactly how I wanted, with no restrictions or government mandates, and make a living at it, too,” Thomas recalls.

Thomas was eager to participate in BirdReturns. On this winter morning in California, he patrolled the dirt embankments separating rice beds to check out the birds using the 170 acres he had flooded for the program.

“This drought is something else. This place usually looks like Ireland right now, with all the lush, ankle-high grass,” he shouted over his ATV as it kicked up a dusty trail. “But these guys are doing all right.” He stopped beside a shallow pool where about 50 Greater Yellowlegs worked the mudflats, heads down and highstepping on their mustard-colored stilts.

Thomas likes the BirdReturns program because it’s easy. “There’s no fines, no regulatory red tape,” he said. Hallstein, the TNC economist, says the model was designed to be friendly to farmers. Contracts are bid out in a reverse auction, which allows farmers to set their own price.

Thomas says that his affinity for birds aside, the program made fiscal sense for his farm.

“We’re being compensated for taking a risk, sure. By delaying our planting, we’re squeezing our seeding into four weeks instead of eight,” he said. “But from purely a business standpoint, you could not give a rat’s bottom about birds, and you’ll make enough money in BirdReturns to make it worth it.”

It was a good deal for TNC. To preserve shorebird habitat via the traditional, land conservation tools—outright purchase or conservation easement—would cost $3,000 to $4,000 an acre. Through BirdReturns, TNC rented the habitat for a small fraction of that cost.

But there was no guarantee the shorebirds would show up. In that respect, TNC was buying futures on shorebirds, betting that they had rented the rice fields in the right places during shorebird migration. It wasn’t a blind bet, though. They had insider information.

Something like this has never been done before, where citizen science joins with NASA imagery to provide habitat conservation—at the scale of a rice field.”

“It’s a little like a ‘Moneyball’ approach to conservation,” Hallstein explains, referring to the Michael Lewis bestseller (and subsequent blockbuster movie) Moneyball, about a high-tech new way to choose baseball players. “The same way the Oakland A’s transformed baseball through precision analytics and sabermetrics, we used big-data sets from eBird to apply analytics to selecting farms in locations with a high probability of bird occurrence. The better data allows us to be more efficient and precise in conservation.”

Conservation Meets Cosmos

The data analytics side of the BirdReturns equation resembled something like conservation meets cosmos.

“Something like this has never been done before,” said the Cornell Lab’s Steve Kelling, “where citizen science is joined with high-performance computing and NASA satellite imagery to provide habitat conservation at a very fine scale—at the scale of a rice field.”

The supercomputing on the eBird side was partially funded by NASA, along with the Leon Levy Foundation and the Seaver Institute. All three organizations saw this project as a way to connect space-age technology with on-the-ground conservation. For eBird, BirdReturns was a golden opportunity to flex its big-data muscles with tangible habitat benefits for birds.

eBird statisticians and computer scientists used the checklists in the database to build predictive models of where shorebirds would be present throughout the Central Valley in February and March. The results were like a weather map for birds, showing where clusters of shorebirds would congregate. These shorebird forecasts, paired with NASA imagery of surface water availability across the Central Valley, made it possible to see where wet habitat was needed.

”This project couldn’t have been situated in a better area for eBird, because the whole region is full of eBird checklists,” said Kelling.

Two of the eBirders sending in those checklists were Linda Pittman and Karen Zumwalt. They were birding some pools just west of Sacramento on a February evening, catching the last volleys of waterbirds over a gravel road before sunset. Both retired, they now bird fulltime. “They call us the ‘valley girls’,” chuckled Pittman, nudging Zumwalt with an elbow.

On this night they had already counted 50 Northern Pintails, 20 Great Egrets, 300 Tundra Swans, and eight Long-billed Curlews when something caught the corner of Zumwalt’s eye.

“Oh, there go some coots!” she said, smiling at the stocky little fellows flip-flopping across the road like snorkelers in flippers. Turns out, of all the 667 species on her life list, American Coots are Zumwalt’s favorite. “I don’t know; there’s something about them. They have cute feet.”

Together, Pittman and Zumwalt put up nearly 2,000 checklists on eBird last year. When they heard through the Central Valley Birding Club that their sightings were going to be used for a ricefields conservation project, they began plotting daytrips to places that hadn’t received much eBird coverage.

“Suddenly, it’s not just another birding trip. You know you’re contributing to scientific data collection and to actually creating habitat for the birds you see,” said Pittman. “It makes you bird a littler harder. It gives you the urge to cover everything.”

The Central Valley Birding Club organized several birding blitzes to get their 500 members out to target areas in an organized fashion, much like a formal bird survey might be planned. But unlike a professional monitoring program, which might cost several thousand dollars, the eBirders donated their data for free.

“This was the original vision for eBird,” says the Cornell Lab’s Kelling, “Directly applying bird-watcher checklists to the conservation of birds.”

Waves of Shorebirds

BirdReturns will be back this fall, but the market environment could be even more challenging. As the drought drags on, farmers may not receive their allotments from local and state water projects. The U. S. Department of Agriculture has forecast a 20-percent decline in California’s rice crop.

Hallstein, the TNC economist, says the market-based mechanism will still be able to put flooded rice fields in the Central Valley.

“Even in a drought, creating wetland habitat is still cheaper for some farmers than others. The reverse auction mechanism allows us to identify those farmers who can create habitat most economically,” he said. “We expect to pay farmers more on average for wetland habitat this year. Higher prices mean we’ll likely be able to pay for fewer acres total. But that’s okay, because we know that any habitat created during a drought year like this one is incredibly valuable for shorebirds, because it may be some of the only habitat available.”

Kelling and the eBird team are preparing new models of bird occurrence and abundance for the Central Valley this fall, as well as all along the Pacific Flyway. In the future, the Cornell Lab plans to reach out to regional and local conservation groups to get timely habitat on the ground for full-life-cycle conservation of species such as Dunlin, which nest in the Alaskan Arctic and winter as far south as Baja California.

Altogether, the Dunlin flocks recorded this spring in BirdReturns numbered more than 20,000 individuals, which represented about 20 percent of the entire Central Valley wintering population taking refuge in the project’s flooded rice fields. About 300 of those Dunlins were pecking around the muddy clumps in one of Amelia Harter’s fields one February afternoon, soon to be joined by a flock of incoming Long-billed Dowitchers, and then Black-necked Stilts.

So it went on throughout the day, wave after wave, an eBird predictive migration model come to life. The shorebirds didn’t know this water was put there for them. But Harter did.

“It feels like such a personal accomplishment to be able to provide this habitat for these shorebirds,” she said. “We’re part of their world here in the Pacific Flyway. I’m just glad we’re able to feed them as they come through.”

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you