Bird Cams Viewer Spots Montana Ospreys in Texas

By Michael Levin November 25, 2014

Live bird cams have all the makings of a Hollywood blockbuster. We get an intimate, birds-eye view of the stars, and can’t help but fall in love as we watch their story unfold. The birds are practically celebrities. So imagine the surprise of Sally Mitchell, an avid watcher of the Cornell Lab’s Montana Osprey cam, when she met one—all the way down in Texas.

Not 5 miles from her home in Rockport (near Corpus Christi), Mitchell was walking along the beach taking photographs of local egrets. “I heard an Osprey call,” she said, “which was unmistakable after having watched the nests so often online.” She looked around, camera swiveling, and spotted one sitting on a nearby light pole.

Peeking through the lens, Mitchell did a double take. A baby blue smudge on the bird’s left leg caught her eye, a band with bold, white writing reading “M8.” “I knew he must have been from Montana,” Mitchell said. It was the same kind of band the Montana Osprey Project uses to identify birds that hatch around Missoula.

Mitchell passed her photos along to Dr. Erick Greene, a professor at the University of Montana and part of the research team that runs the Montana Osprey Project. He quickly confirmed that he had banded this particular bird in July—appropriately enough, at a nest on the home field of the local baseball team, the Missoula Osprey—and only a mile and a half away from the Bird Cams Osprey nest in Hellgate Canyon, Missoula, Montana.

“The first picture I opened, I knew instantly it was one of our birds,” said Greene. “These are such rare events, and I just got this tingle.” The rarity of resighting a bird without any kind of tracking device cannot be overstated. Along with Rob Domenech of the Raptor View Research Institute, Greene has banded upwards of 200 Ospreys since the Montana Osprey Project began in 2006, and only three of those birds have ever been resighted.

Greene got back to Mitchell with the exciting news and asked her if she would give the bird a name. She settled on Emmett, a clever echo of his identification number.

Mitchell said she plans to keep watching and photographing Emmett during his stay in Texas. Dr. Greene looks forward to gaining new insights into Osprey behavior, much as he did with the Osprey cams. “The first time we put up a camera, in the first five minutes I was watching it, I was seeing stuff I’d never, ever seen before,” said Greene. Mitchell’s photography will help Dr. Greene fill in the gaps about a bird whose previous life we already know so much about.

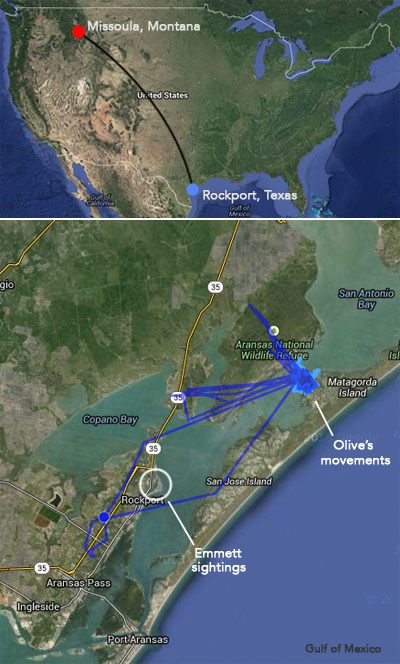

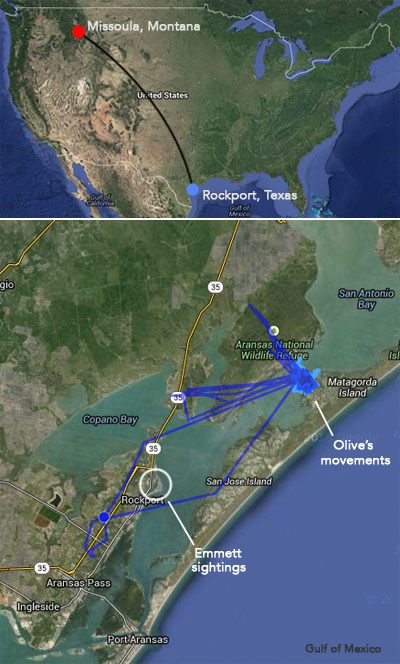

Turns out, Emmett isn’t the only Missoulian in eastern Texas, which is a popular wintering destination for Ospreys. Real-time location data shows that an adult female Osprey named Olive, who nested this year less than 15 miles from Emmett’s nest, has settled within 20 miles of him in Texas. She’s even given Rockport a flyby every now and again. Another Montana bird, named Rapunzel, is staying just up the coast near Galveston for the winter.

Other satellite tracking research has shown that Ospreys from certain breeding areas often do winter in the same regions. For instance, Ospreys from the Northeast work their way down the Atlantic coast, then island-hop through the Caribbean and Cuba to South America; whereas West Coast Ospreys tend to hug the shoreline and settle in Baja California. Midwestern Ospreys head south on similar paths but seem to disagree about which spot is best. Some peel off west to Mexico’s Pacific coast, while others head east for the Gulf of Mexico. Regardless, Greene said, having two birds end up so close to each other at both ends of their migration is rare.

Emmett’s migration remains pretty mysterious. We know he flew lengthwise across the country, logging at least 2,000 miles to make the trip, and that juvenile Ospreys figure out their own migration routes and destinations. What we don’t know is what the birds do while on the move, or why they choose certain areas to eventually settle down in.

“He probably won’t migrate back next summer—he’ll probably stay for another full year,” said Greene. Juvenile Ospreys stay up to four years in their wintering grounds, presumably honing their fishing skills so they can provide for a mate and young when the time comes. Take heart, Missoulians—and in a few years, keep an eye out for that M8 band. “Males tend to settle closer to where they are born,” Greene said. “My prediction would be that Emmett will probably end up somewhere in that general area [of Missoula] up in Montana.”

For now, Mitchell is more than content to have Emmett nearby. She sets out regularly to play paparazza. “I’ve checked his two favorite sites almost every day,” she said. She marveled at the sheer odds involved in spotting him—“When you think of the territory they cover and the birds that have been banded, that I should see him is miraculous,” she said.

So if you pass through Rockport any time soon, keep an eye out for blue bands and a white belly. Just be careful asking for any autographs.

More stories from our Bird Cams project:

- A “Birder on the Ground” Captures Lovely Behind-the-Scenes Photos of Cornell Hawks

- Behind the Scenes of Our Bird Cams Project

- Bird Cams Project Puts an Albatross Outside Your Window [Living Bird magazine]

(Dr. Erick Greene and the Montana Osprey Project are partners in the Cornell Lab’s Osprey cams. Tracking of Olive and other Montana Ospreys is conducted by Rob Domenech, the Raptor View Research Institute, and MPG Ranch—where you can follow further movements of Olive, Rapunzel, and other Ospreys.)

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you