The Redpolls are Coming! The Redpolls are Coming! (And Siskins, Too)

By Gustave Axelson and Emma Grieg February 3, 2015

Time to put out the call like Paul Revere—redpolls, as well as siskins, are making a southward push into the Lower 48 states right now in their winter migrations. (Just in time to be counted in the GBBC in a couple weeks!)

About every other year, cold winter winds blow flurries of two boreal birds—Pine Siskins and Common Redpolls— down from Canada to scatter about the Lower 48 states. It’s an irruption cycle driven, scientists think, by shortages in the crop of conifer seeds (such as spruces and pines) and catkins (such as birch and alder) in the North.

In search of food, flocks of siskins and redpolls travel south and fan out across the United States, often finding a steady supply of forage and refuge at backyard bird feeders. During the winter irruption of 2008–09, siskins were spotted at 50 percent of the 10,000 Project FeederWatch reporting stations across the continent, more than twice the typical count. The every-other-year irruption pattern would mark this winter for another irruption.

Marshall Iliff, a project leader for eBird, says the siskins are leading the way so far this winter.

“This year is a really good one for siskins,” Iliff says.”Whenever siskins reach Florida and south Texas, you know something special is afoot.

“Redpoll numbers are up from last year but have not measured up to winter 2012-2013, which was excellent. They do appear to be making a late January push, which is not unusual, so we can expect their numbers to increase along their southern margins into February and early March.”

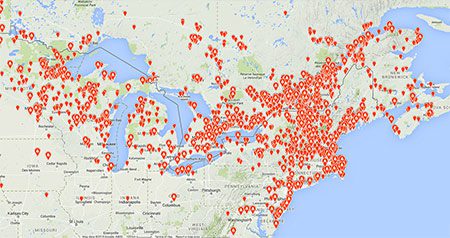

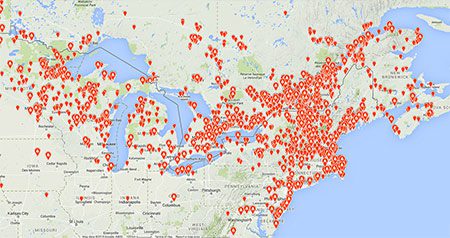

A look at recent eBird maps for each species shows just how far south these species are stretching.

Pine Siskin Spinus pinus

Gregarious flocks of Pine Siskins descend en masse when they find a source of seeds. At bird feeders, they’re all atwitter in frenzied motion, fluttering while they feed and making constant wheezing sounds (contact calls emblematic of the tight social bonds within their flock). Siskins are streaky brown finches that can be confused with House Finches and goldfinches, but they’ve got a small, sharply pointed bill—and telltale (though sometimes faint) yellow splashes near the wing tips and tail.

Siskins in steep decline

Unfortunately, the Pine Siskin was one of 33 bird species on the 2014 State of the Birds report list of Common Birds in Steep Decline. While their global population likely still numbers in the tens of millions, siskins counts in the annual Breeding Bird Survey have dropped more than 75 percent since 1966. They’re part of a suite of northern breeding birds that are under intense habitat fragmentation pressure from timber, oil, natural gas, and mineral extraction in the boreal forest of the northern U.S. and Canada. According to the Boreal Songbird Initiative, an area twice the size of Japan has already been cut out of the boreal forest, and one-third of what remains is already slated for industrial development of some kind.

Common Redpoll Acanthis flammea

Much like siskins, redpolls are peripatetic busybodies at bird feeders, emitting electric zapping calls as they bustle about gleaning seed. They are also brown streaky finches that gather in large communal flocks, and at first glance they also might be mistaken for a House Finch. But if you look closer, you’ll see a distinctive purplish-red cap cocked forward on their head, and black on their face around the bill—no other finch has that.

Look closely at your redpoll visitors

OK, you’ve got redpolls crowding around your feeder, but wait, one of them looks slightly different, paler than the rest with a snow-white chest. Congratulations, you’ve just won the redpoll lottery—a Hoary Redpoll, Acanthis hornemanni. Hoaries are a subtly different species, and during irruptions there’s a chance in every flock that one or even a few paler Hoary Redpolls could be mingling among the Common Redpolls. Hard-core birders will travel far and put forth a lot of effort to notch a Hoary on their life list. If you see one, enjoy it on your list while it lasts. Ornithologists are constantly bickering over whether there’s enough genetic evidence to support defining Hoary Redpoll as a distinct species, and someday soon Hoaries may be lumped back in with the Commons.

Feeder Tips for the Irruption

Your best bet for catching a wave in the siskin/redpoll irruption is hanging a thistle or nyjer seed feeder, either a plastic tube or a mesh sock. All finches love nyjer and thistle, but they’re especially effective at attracting siskins and redpolls by the flockful. They also may hang around sunflower seed feeders, scavenging seed bits left over from the bigger-billed birds that can open up sunflower shells. Flocks can be 100-birds strong or more, so if you get a rush you may want to put up multiple feeders. You’ll also find siskins dangling upside down on the seed heads of plants sticking up in your yard.

Where did all these birds come from?

Generally speaking, siskins and redpolls are from Up North, but their ranges are separated by degrees of latitude (see their range maps). Pine Siskins have a breeding range that runs across the boreal forest of Canada and the northern United States, with an offshoot that runs south among high-elevation conifer forests along the Rocky Mountains all the way to Central America. As for Common Redpolls, the best way to envision their breeding habitat is to look at the top of globe—their range stretches along the high boreal forest and tundra that circles the Arctic Ocean at the top of the world.

Happy Wanderers

Apart from their two-year irruption cycle, siskin and redpoll population movements can best be described as erratic. It’s almost as if somebody shook up a bottle of winter finches and let it spray across North America every other year. Research on Pine Siskins during the 2008–09 irruption appeared to reveal two possible patterns. Siskins caught and tagged with leg bands in the South (for example, Alabama and Georgia) were later recovered due north (Minnesota and Michigan), whereas siskins banded in the Northeast (New York and Pennsylvania) were found in the Canadian West (Manitoba and Alberta). So there could be two separate siskin travel highways, a north-south route and an east-west route. Redpolls, on the other hand, are all over the place. One redpoll banded in Michigan was found in Siberia; another banded in Belgium was recovered two years later in China.

Hardy Troopers in the Cold

Siskins and redpolls have excellent strategies for coping ramp up their metabolic rate and put on 50 percent more winter fat. Redpolls sometimes tunnel into the snow to spend the night in their own insulated snow cave. Both species have throat pouches for storing extra seed to eat later. Siskins can store as much as 10 percent of their body mass in their throat (the equivalent of 60 hamburgers for the average human), plenty of energy to get through a subzero night.

For more on redpolls and bird visitors to your birdfeeders:

- Project FeederWatch

- BirdCast: bird migration forecasts in real time

- Explore where the birds are with eBird

- Help Us Track Sick Birds With Project FeederWatch, a blog post with tips if you see any sick birds at your feeders

- From Many, One: How Many Species of Redpolls Are There?

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you