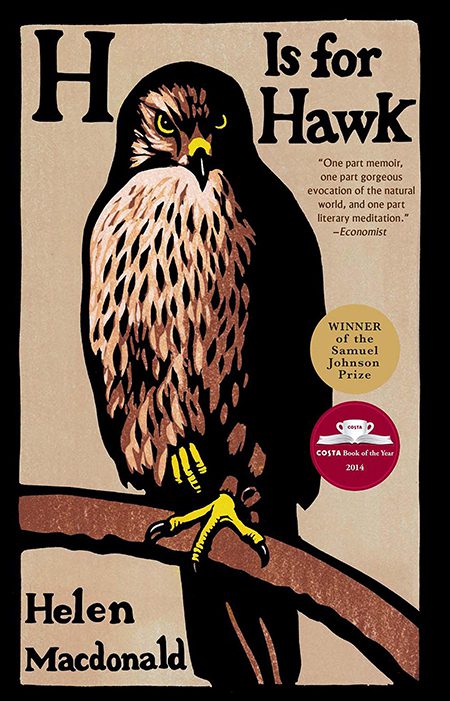

A Falconer Reviews Helen Macdonald’s Acclaimed Bestseller, H Is for Hawk

By Tim Gallagher, editor of Living Bird magazine March 23, 2015

Last fall, a remarkable memoir called H is for Hawk, by Helen Macdonald, took the United Kingdom by storm, winning two prestigious awards and rising to the top of the bestseller list. It’s just been released in the U.S. and promises to do the same here. Last fall, our own Living Bird magazine published a review that highlighted Macdonald’s lyrical writing —but as a lifelong falconer I also give her high marks for providing a window into the minds of falconers and their birds.

On the surface, H is for Hawk is a falconry book chronicling the training of a Northern Goshawk, and yet it is so much more. It is a brilliantly written memoir of the darkest time in Helen Macdonald’s life, as she struggled to cope with the sudden death of her father, noted photographer Alisdair Macdonald. The two had been close her entire life. Some of her fondest childhood memories are of hiking through fields together, with binoculars hung around their necks, as she looked at birds and he at airplanes.

What makes H is for Hawk special is how Helen Macdonald chose to deal with the grief she felt after her father’s death—by dropping out of human society and spending months alone, training and hunting with a hawk. This is not as strange as it might sound to a non-falconer. She had been working with raptors since childhood and was already an accomplished falconer. She knew that the kind of concentration required to train a hawk would be the best possible distraction for her. What is interesting is her choice of bird: a goshawk—one of the wildest, most difficult to train of raptors.

Macdonald is fascinated by falconry’s ancient roots, and she covers its history and lore excellently in parts of H is for Hawk and an earlier book, Falcon. It’s a fascination I share. As a 12-year-old, the first book I ever read about falconry was a translation of De Arte Venandi cum Avibus (On the Art of Hunting with Birds), by 13th-century Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. It felt almost like Frederick was speaking to me from across the centuries, guiding me in my earliest falconry endeavors. Many years later, I traveled across Italy, visiting important Frederick II sites—where he was born, where he lived at various times, where he died—and wrote about the experience in my book Falcon Fever. I ended my journey at the cathedral in Palermo, Sicily, leaving a pair of my Peregrine Falcon’s bells at the foot of Frederick’s sarcophagus—alongside the fresh flowers that people still leave there all these centuries later.

I’ve always felt a strong connection with falconers in centuries past. What I learned from Frederick and other authors was how different the training of a raptor is from any other kind of animal training. Hawks are not social animals like dogs or horses—or people. (Only a handful of species—such as the Harris’s Hawk—has any kind of social structure beyond the pair.) Most raptors are loners. There’s no warmth there. They come together as pairs to breed, but for most of the year they lead solitary lives. If they weaken; if they fall ill or become injured, they die. That’s it. There is no pack mentality. No dominance and submission. No hierarchy of power.

So punishment doesn’t work with hawks, only positive reinforcement. You feed them. You care for them. You must show them only kindness, no matter what a hawk might do to you. If it bites you, claws you, or grabs your bare hand, sinking its talons deep into your flesh, you must remain impassive, and wait—sometimes for a long time—until the bird deigns to release its hold. You must be a model of patience and gentleness with a hawk.

This is something I find endlessly fascinating about falconry: the fact that even if you’re a mighty king, or an emperor like Frederick II, you must come to your hawk, hat (or crown) in hand, like a supplicant. It’s an unusual relationship, the height of self-denial, perhaps most akin to that of a medieval monk, clad in a hair shirt and sitting alone without comfort of any kind in a cold stone cell.

The early stages of training a hawk (especially one that is wild-trapped or was raised in a free loft) are all about getting the bird accustomed to being close to a human. Sometimes it’s difficult even to get them to sit on your fist, let alone feel comfortable there. And you can’t even look at them, because, in the fang-and-claw world of predators, a fixed stare often precedes an attack. So you must look away, casting your eyes downward through most of the training process.

I remember all too well my early experiences in training a fresh-trapped Cooper’s Hawk—a mid-sized cousin of the goshawk—when I was in my teens. It was a lonely process—for the first two weeks walking back and forth late into the night with the bird on my fist: first in my room, then in my yard, and finally in the field, where I trained her to return to me when I blew a whistle. I’ll never forget the first time she caught wild game, a common House Sparrow, just three weeks after I trapped her. My mind filled with doubt. Would she let me approach her and pick her up from her kill? Or would she fly off with the bird she had caught and resume her life in the wild? She could easily have done that—but she didn’t. Instead she stepped easily up to my fist, finished her meal, cleaned her beak, and shook her feathers—called a “rouse” in falconry parlance, a sure sign of contentment.

At that moment I knew that all the hard work had paid off, and we were a team. I flew her for the rest of the season, during which she caught many more birds and a few rabbits. I released her back to the wild the following spring. This was an ideal situation for the hawk, which got through her difficult first winter—when a majority of young raptors die. And she was released in the mildest time of year.

All falconers are stoics—or at least we try to be. We train ourselves to hide our innermost feelings. We have to, or we’d never get anywhere in the training of a hawk. To these birds, we must always present ourselves as an unshakable rock—an impassive, immovable presence in their lives. Emotions make raptors nervous. They’re the only ones in this relationship who can show their feelings. Unfortunately, I think we falconers sometimes carry this impassivity into our human relationships, holding our feelings in check, hiding our emotional and spiritual anguish from everyone in our lives. In the darkest nights of our soul, we all too often stand alone—with a fierce, unloving raptor on our fist.

This is where Helen Macdonald was mentally and emotionally in the months following her father’s death. Even in the heart of Cambridge, she was cut off from her friends and family, by her own choice. But she did have two soul mates in this endeavor—a wild-eyed goshawk named Mabel and the ghost of author T.H. White, who had trodden this same path in the 1930s. White, famous for writing The Once and Future King, The Sword in the Stone, and other classics, dropped out of human society, moving into a hovel of a cottage in the English countryside to train a goshawk. It was an utter disaster, ending ultimately with the bird’s escape. White’s book, The Goshawk, chronicles his misadventures in great detail. I remember reading it as a teenager and cringing at times at his ineptitude with the hawk. And yet, his writing was so brilliant, I couldn’t help but read it again and again.

White never really stood a chance of succeeding with this hawk. He was a complete novice—had never even handled a bird of prey previously—and yet here he was, trying to train the most difficult raptor of all. This is something that a non-falconer reading The Goshawk or H Is for Hawk might not get. There’s a world of difference between, say, a falcon and an accipiter (such as a Northern Goshawk, Cooper’s Hawk, or Sharp-shinned Hawk). I’ve flown enough falcons and accipiters to know that they are vastly different animals. (It didn’t surprise me when DNA work revealed that falcons are more closely related to parrots than to accipiters.)

All of the accipiters can be difficult to train, but the goshawk is the worst, because it’s so big and strong and fierce. There’s even a falconry term called “yarak,” which refers to a state of bug-eyed, murderous intensity goshawks get into sometimes. They definitely have a reptilian edge to them. If birds are truly dinosaurs, perhaps it’s not difficult to imagine the goshawk’s distant kinship with Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor! White should never have attempted training a goshawk until he’d had some experience flying easier birds. (He did later go on to become an accomplished falconer, successfully flying a goshawk and a number of Peregrine Falcons and other birds.)

Helen Macdonald could certainly have taken the easy way out and spent that season of despair flying a well-tempered Peregrine Falcon or a Merlin, but she didn’t. She had demons to conquer—both hers and T.H. White’s. I won’t spoil it and tell you how things went with Helen and Mabel, but instead encourage you to read the book. H is for Hawk is a courageous tour de force of writing—emotionally honest and harrowing in its intensity. I’m grateful she was willing to share her story.

Tim Gallagher is the editor of Living Bird, the Cornell Lab’s member magazine. He’s pictured here at age 14, with a Red-tailed Hawk and its jackrabbit kill.

For more reviews:

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you