The Almost Impossible Task of Filming Songbirds in Flight

By Su Rynard

January 13, 2016Editor’s note: This is a guest post written by Su Rynard, the director of The Messenger, a documentary about songbird declines. We loved the movie (read our review), which features closeup, slow-motion film of songbirds in flight. We asked Rynard how she managed to capture such spellbinding footage—here she explains in both video and writing.

One of the most daunting tasks for any film director is the process of visualizing the film. While the idea for a documentary film featuring songbirds is exciting, these little creatures live high in the treetops, are not residents of one place, and most migrate at night, high in the sky, out of plain sight. How could we possibly film it? This was the question that kept me awake at night.

Many of you will remember the outstanding 2001 Oscar-nominated film Winged Migration, which showcased the immense journeys routinely made by birds. But that was a very different kind of movie: they worked with much larger birds such as geese and cranes, hand raised from birth, and filmed by 14 different cinematographers from ultralight aircraft, balloons, motorboats, and other craft. Easy right?

We were two small companies—SongbirdSOS Productions and Films à Cinq— with a tiny budget and, in my case, a home office. But we did have imagination, and in one of my many worried sleepless nights, the eureka light bulb went off. Enter AFAR!

The Advanced Facility for Avian Research is a globally unique research facility where people like Dr. Chris Guglielmo of Western University study avian physiology and behavior. Research done here helps us understand how birds meet the demands of long distance migration and respond to environmental stressors such as habitat change. The facility offers unique equipment—and it contains the world’s first wind tunnel for birds that is capable of simulating altitude conditions.

Lucky for us Chris agreed to meet with us and listen to our crazy proposition: to film tiny songbirds in emulated nocturnal migration in the AFAR wind tunnel.

Birds are wild creatures, so Chris had to obtain a permit from Environment Canada for every bird we filmed. In the spring, each bird had to be captured then safely housed in an aviary. AFAR had the most stringent guidelines to ensure the birds were healthy and well adjusted to their new surroundings. Over the next few weeks their staff worked for several weeks habituating the birds to fly in the tunnel and by summer we were ready to roll.

Related Stories

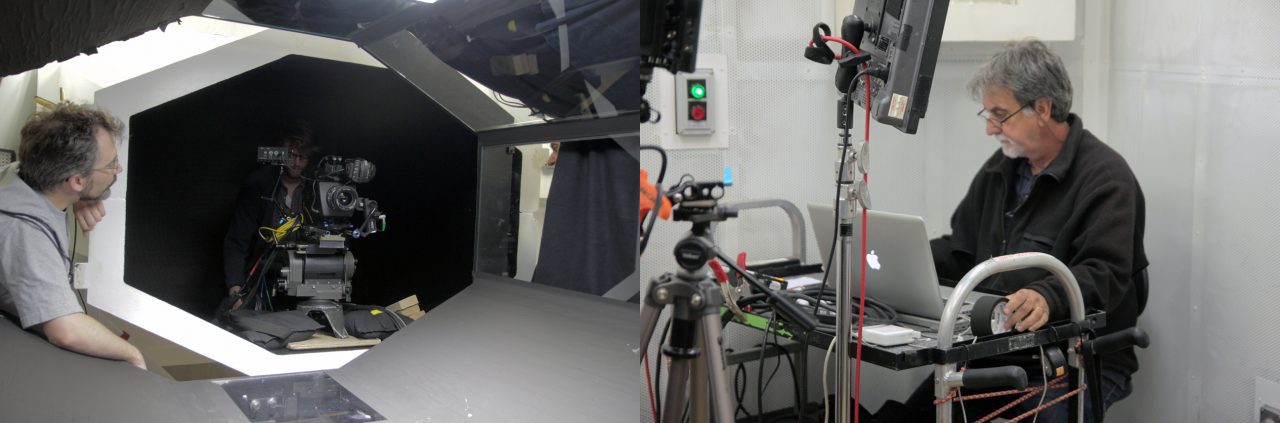

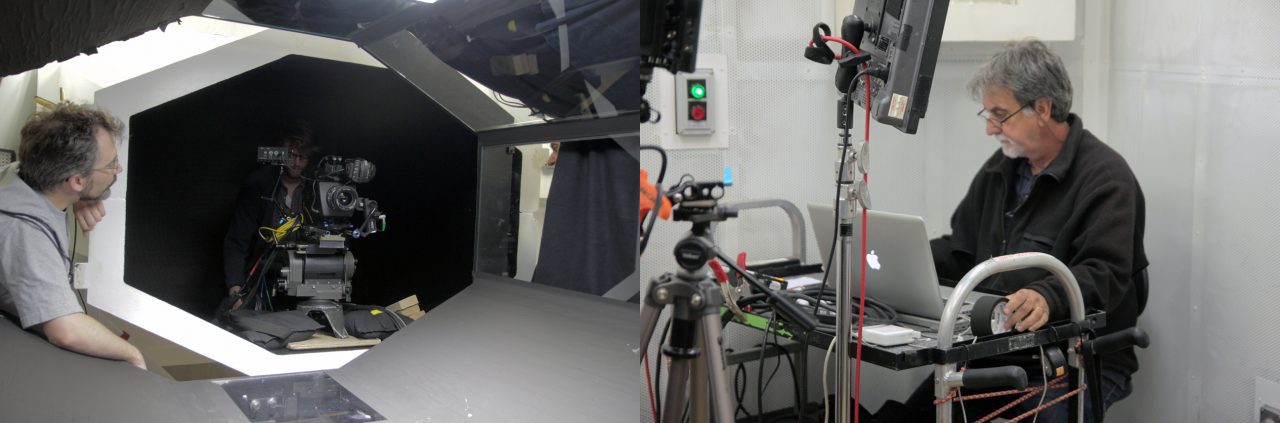

The filming was super intense and very challenging as we didn’t know if what we were trying to do could be done at all. With a small crew, a Phantom camera, and a series of very fast prime lenses, we set up for two days of filming. The camera allowed us to shoot at up to 1,000 frames per second, allowing us to take a quarter- to half-second of flight and transform it into a 5-10 second clip. But it could shoot for only 2 seconds at a time and could keep only about an inch in focus at any moment.

“One of the major difficulties,” cinematographer Daniel Grant recalls, “was that it is nighttime flying conditions that are being replicated for the birds in the tunnel, so the wind tunnel is kept very dark, and any light is likely to confuse the birds. But in order to record at high frame rates, you need quite a bit of light.”

Nonetheless, the results were spectacular. Dr. Christopher Guglielmo describes the experience as a positive one, “When you look at the kind of footage The Messenger shot, it’s unique. I’ve never seen anything like it and I think it is going to have a big impact on the way people look at birds, the way people think about science and the link between the research and the other things we want for these birds, for their conservation, and for the environment”

This is an excerpt from a longer article—read the full story at The Messenger website. Here’s where you can see The Messenger now. If it’s not playing near you, here’s how to request a screening.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you