Recreating a Home Where Buffalo Can Roam (and Burrowing Owls, Too)

By Ben Pierce

From the Summer 2016 issue of Living Bird magazine.

Burrowing Owl by Ray Hennessy via Birdshare. July 6, 2016The American Prairie Reserve north of the Missouri River Breaks in eastern Montana is a Burrowing Owl’s paradise, a vision of the American West where sweeping grasslands roll toward a limitless horizon. Here, the long-legged, little sandy owls find wide-open spaces and plenty of potential nest holes excavated by foxes, ground squirrels, and, most commonly, prairie dogs.

Such inviting environs for Burrowing Owls are getting harder to find in the modern West. The species once ranged as far east as western Minnesota, but as shortgrass prairie was plowed up and developed, fewer prairie dog towns were left to provide nesting habitat. Today the Burrowing Owl is listed as Endangered in Canada and Minnesota, Threatened in Colorado, and a species of special concern in seven other states, including Montana.

“We’ve taken the most productive land on the prairie and converted it to agriculture,” said Marco Restani, a professor of biology at St. Cloud State University who has studied Burrowing Owls in Montana. “If the prairie dogs disappear from poisoning or plague or plowing under, the Burrowing Owls are gone.”

According to the 2013 State of the Birds Report, 85 percent of grassland bird habitats are privately owned, meaning conservation for grassland birds requires cooperating with private landowners or outright buying them out. The former is a tricky exercise in relationship-building, while the latter is often cost-prohibitive. But the American Prairie Reserve is doing both, with the financial backing and business expertise of New York City investment bankers and Silicon Valley executives. And while it’s ruffling a few feathers among local ranchers, some conservationists say it’s the best hope for recreating and restoring a prairie ecosystem with large tracts of open land for threatened species such as Burrowing Owls, Ferruginous Hawks, Mountain Plovers, and Greater Sage-Grouse.

A Bold Plan to Save Montana’s Prairie

In 1999, the Nature Conservancy issued a report that identified areas of the Northern Great Plains critical to restoring the habitat of the prairie ecosystem. The findings highlighted the region near the Breaks as a top priority for grasslands conservation. Shortly after the report was published, the World Wildlife Fund launched a conservation initiative that concluded the best way to protect Montana’s shortgrass prairie was through the formation of a freestanding entity focused solely on preserving the ecological integrity of the Northern Great Plains. Dr. Curt Freese, director of WWF’s Northern Great Plains Ecoregion Program, organized the founding of the American Prairie Reserve in June 2001.

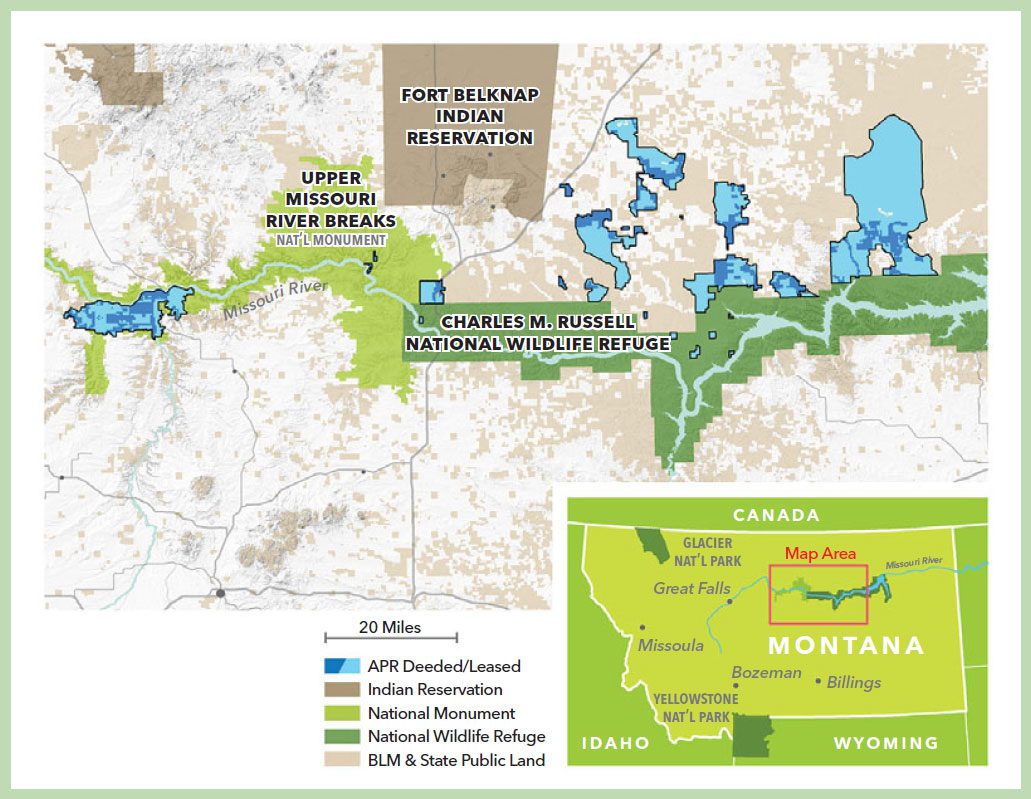

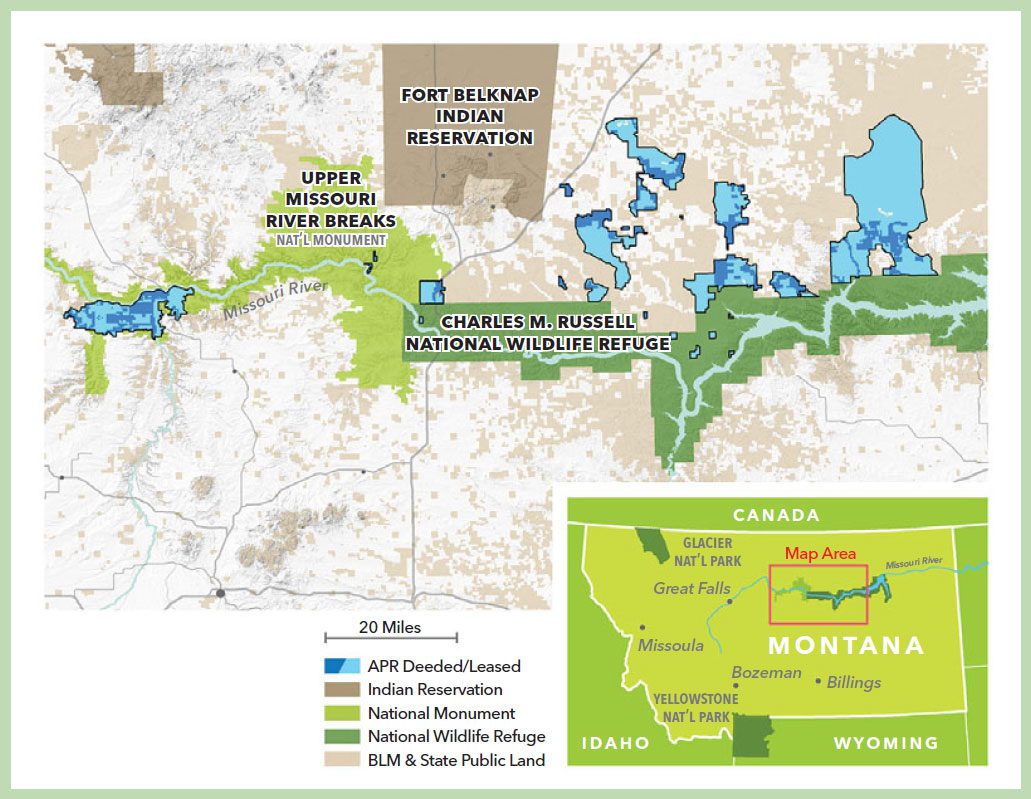

The nonprofit’s audacious and controversial mission is to stitch together a patchwork of 3.5 million acres of public and private property—connecting lands around the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument—to develop a contiguous prairie-based wildlife reserve complex 50 percent larger than Yellowstone National Park.

“The project will benefit bison, Burrowing Owls, Mountain Plovers, sage-grouse.”

—Steve Hoffman, executive director of Montana Audubon

Thus far, the reserve has acquired 305,000 acres of deeded and leased private, BLM, and state land. It is the largest privately funded conservation effort in the U.S., with thousands of backers who chip in $20 or so annually and many wealthy donors, including the Mars family, Swiss entrepreneur Hansjörg Wyss, and Telosa Software CEO Susan Packard Orr. The reserve’s president, Sean Gerrity, is a former Silicon Valley consultant who has recruited many venture capitalists to the cause.

“Being privately funded gives us more flexibility,” said Katy Teson, reserve marketing and content manager. “We can act quickly rather than having to move slower through the agencies.”

In 2005, the reserve reintroduced American bison to its prairie holdings. The 16 animals released that year were the first to inhabit that patch of Montana prairie in 120 years. Today, a herd of more than 500 bison share the land with other native prairie wildlife including the black-tailed prairie dog, which the reserve has identified as a keystone species due to its wide-ranging impact on the ecosystem. Prairie dogs, in turn, create and maintain Burrowing Owl habitat by digging out holes in the prairie and trimming the grasses around their towns.

“One thing about Burrowing Owls is that they are dependent on areas with low or little vegetation, so prairie dog towns are critical not just because of the burrows, but so the birds can see well to avoid predators,” said Steve Hoffman, executive director of Montana Audubon.

The reserve aims to create a sanctuary for all manner of native prairie species, including animals such as wolves and grizzly bears that have been pushed out of eastern Montana, in hopes that the public will come to see them, Teson said. She says the reserve could be the third point in a wildlife-watching tourism triangle connecting Yellowstone National Park to the south and Glacier National Park to the west, a Northern Great Plains equivalent to Africa’s Serengeti.

“The reason APR works where it does is because there is an opportunity to restore a large ecosystem where these species can find all that they need,” Teson said.

Not Everyone Is Buying In

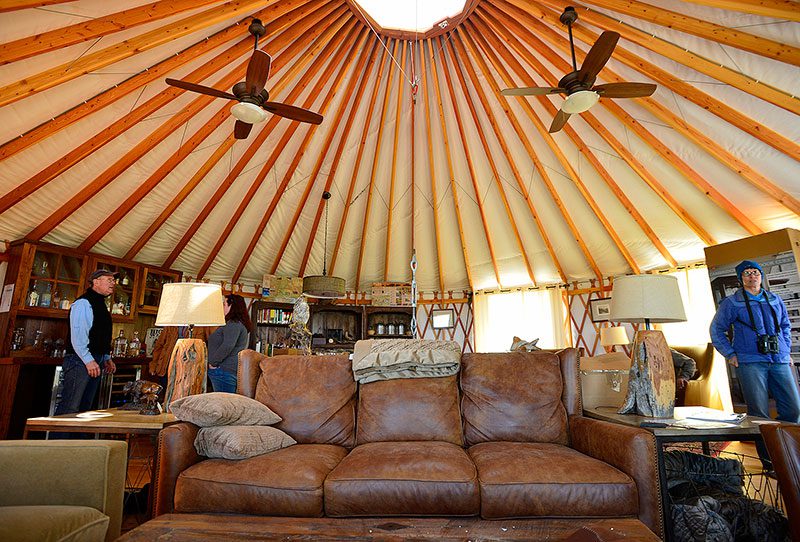

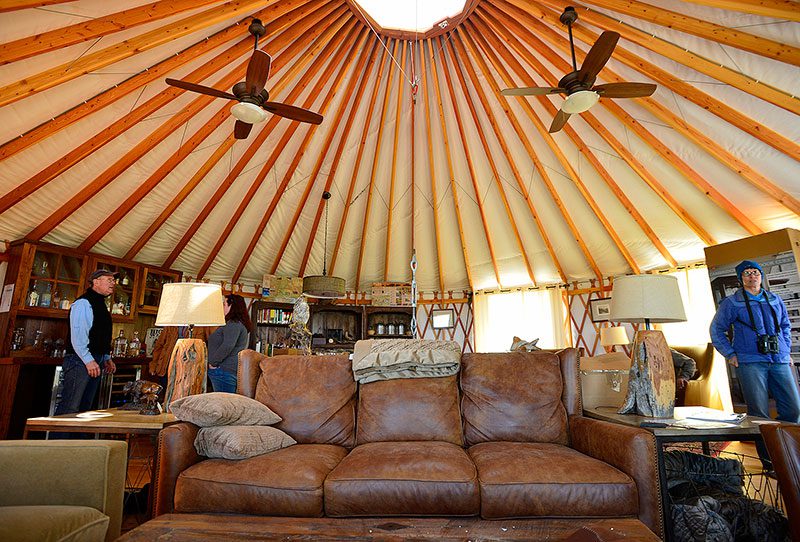

Many in the reserve region have deep concerns about the project. Residents whose ancestors pioneered the prairie are offended when they see Mercedes Benz vans shuttling reserve donors to air-conditioned yurts. And some statements from reserve spokespeople about the region—particularly regarding land stewardship and dwindling rural communities—don’t sit well with those who live on the prairie.

“The claim that the population is declining and the land needs to be claimed and repurposed is factually inaccurate,” said Taylor French, who operates a ranch with her husband in Phillips County. “The misrepresentation of Phillips County as a dying community is an injustice to the vibrancy and resilience of a population that has endured a series of hard times. However, it is also a disservice to the donors and public who trust an organization in their mission for conservation.”

“If a large corporation moved into town and out-competed the mom and pop shops it would make the headlines […], but because the businesses are ranches and the corporation is an environmental entity there is far from a national outcry.”

—Taylor French, local rancher

The reintroduction of bison and the reserve’s vision of converting agricultural land back to native prairie also strikes a nerve. Many ranching families in Phillips County have dedicated generations of good stewardship to restore the prairie from the devastation of the Dust Bowl. They view ranching as having a positive impact on the land and wildlife. Ranching families are also concerned that the reserve’s purchase of properties in the region is driving up land prices, and some fear the reserve ultimately intends to turn its landholdings over to the federal government.

“The main concern with APR’s land acquisition policy is that there is a scarcity of opportunities to acquire land in the area,” French said. “If a large corporation moved into town and out-competed the mom and pop shops it would make the headlines and everyone would sympathize with the small businesses, but because the businesses are ranches and the corporation is an environmental entity there is far from a national outcry.”

In an effort to bridge the gap with ranchers, the reserve founded a subsidiary for-profit company called Wild Sky Beef. Ranchers who partner with Wild Sky are paid a premium for their beef in exchange for wildlife-friendly ranching practices, including prairie dog conservation. Currently, Wild Sky is mostly selling beef to high-end restaurants and grocers on the coasts, but there are plans to expand retail sales throughout the country.

Wild Sky rancher Dave Crasco grazes 50 head of cattle on 1,000 acres in Phillips County. Crasco has seen evidence of black bear and plenty of coyote on his ranch, and he thinks one day grizzly bears will return to the prairie. He said working with Wild Sky hasn’t changed his operation much, and the added bonus he gets for his beef is welcome.

“I have a lot of friends in southern Phillips County where the most resistance is,” Crasco said. “I was only hearing their side of it, and then I got to see what APR was trying to do. The big misunderstanding is everyone thinks they are coming in and doing this radical takeover, but it is a willing buyer and a willing seller, so I don’t see what the problem is.”

Montana Audubon’s Hoffman says that the potential bird conservation benefits are worth the local backlash.

“APR is supporting the local tax base and they only buy from willing sellers,” he says. “The project will benefit bison, Burrowing Owls, Mountain Plovers, sage-grouse.”

But getting buy-in from all involved is often the hardest part of conservation.

“Anytime you have an entity buying up land, you are going to have controversy,” Hoffman says.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you