Racing to Save the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow

Photo essay by Dustin Angell

April 11, 2017

Only about 150 of the distinctive Florida subspecies of Grasshopper Sparrows remain.

Biologists for the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow Working Group perform a health assessment of a sparrow caught during a spring mist-netting effort.

A sparrow in hand is evaluated by scientists.

A parent feeds a chick.

Will the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow make it through the 21st century? Prospects seem bleak, but conservation teams offer reason for hope.

From the Spring 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

The Bird

The Florida Grasshopper Sparrow is one of America’s most imperiled birds. A sparrow subspecies found only in Florida’s dry prairie, it was listed as federally endangered in 1986 after a population decline of about 90 percent. Even with federal protections, the sparrow’s alarming decline continues today. Biologists from government agencies and conservation groups are conducting urgent field research to understand and combat the causes of decline and save this bird from extinction.

The Setting

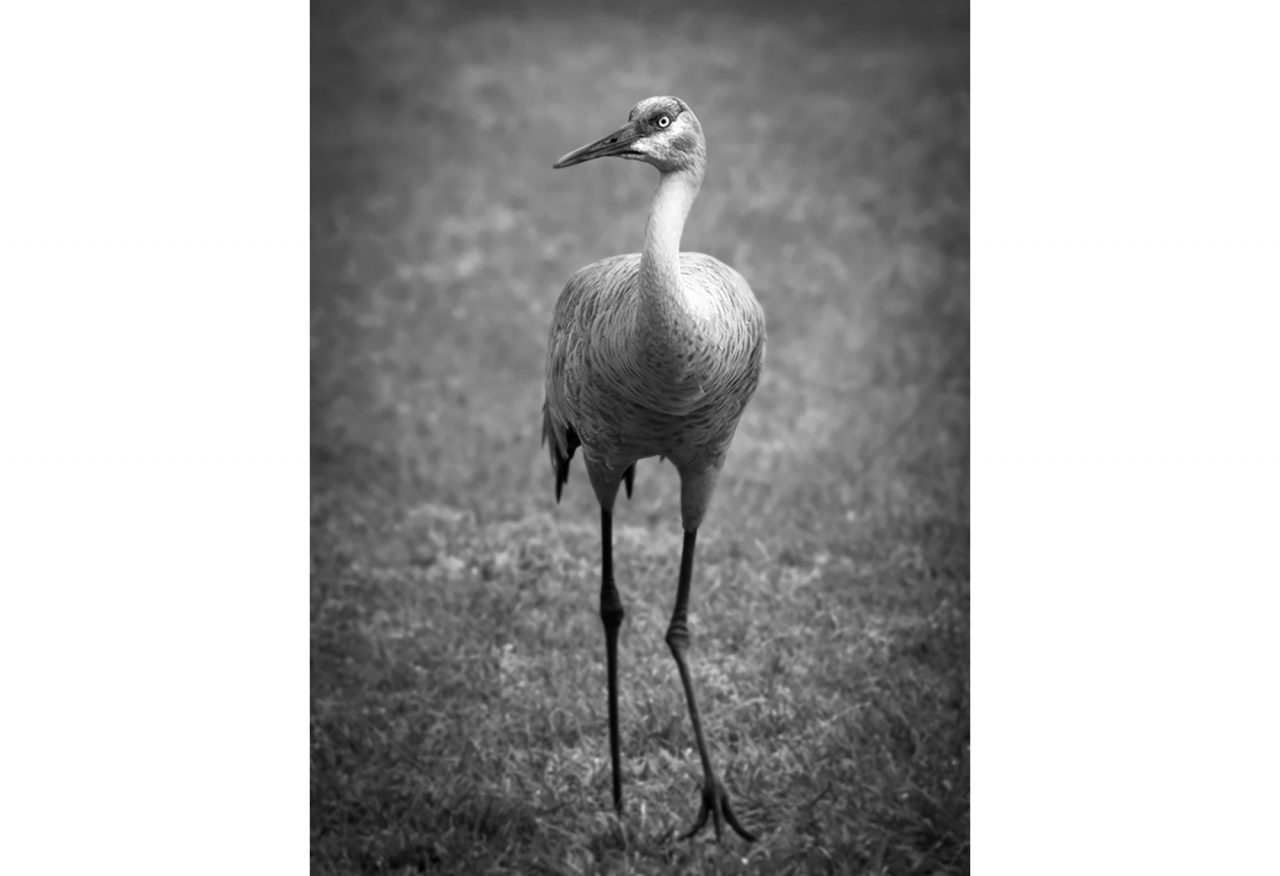

The Florida Grasshopper Sparrow is native to Florida dry prairie, a flat, treeless grassland interspersed with palmetto islands and dwarf oaks. Despite being called dry, this prairie often floods during the wet season from May to October. More than 20 bird species rely on habitat in and near the dry prairie, including Burrowing Owls, Sandhill Cranes, and Eastern Meadowlarks.

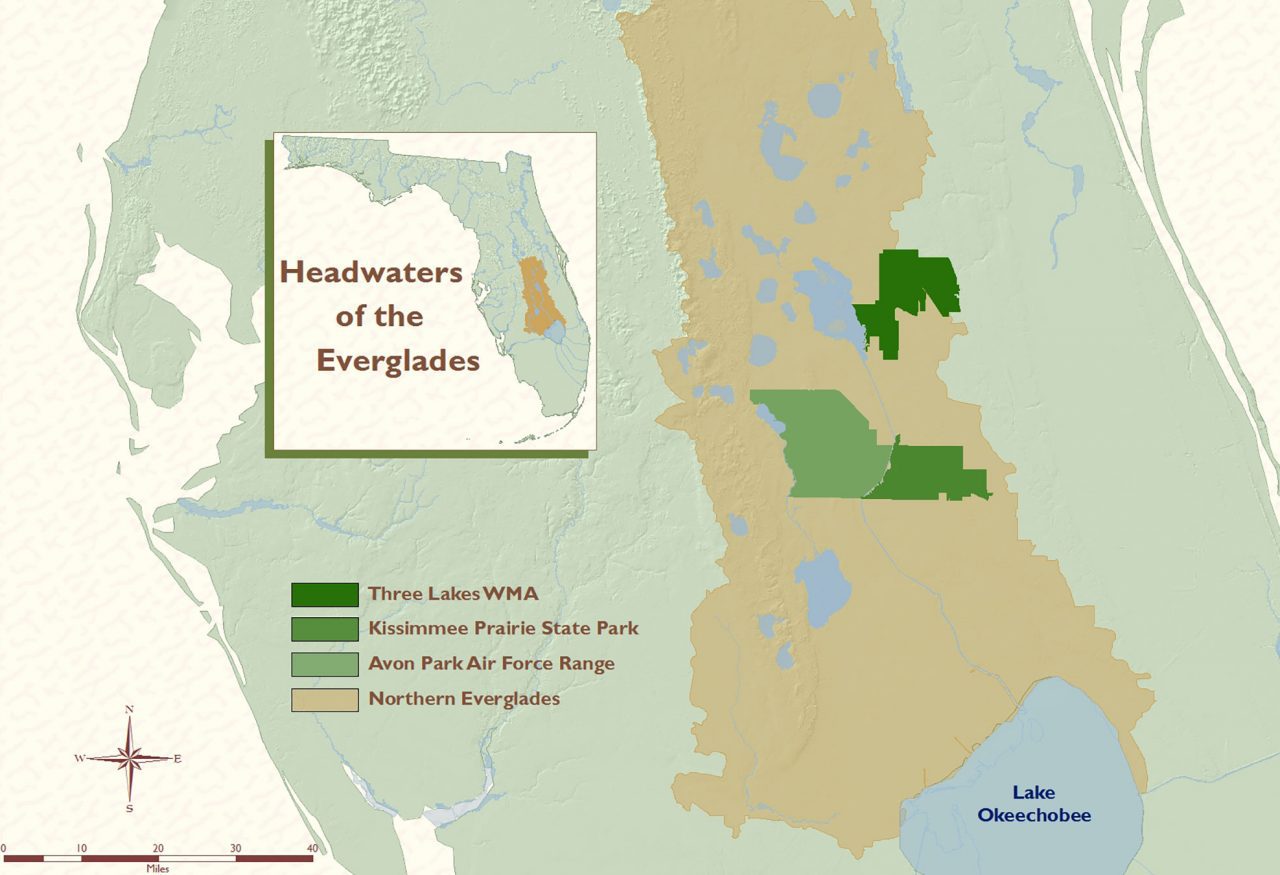

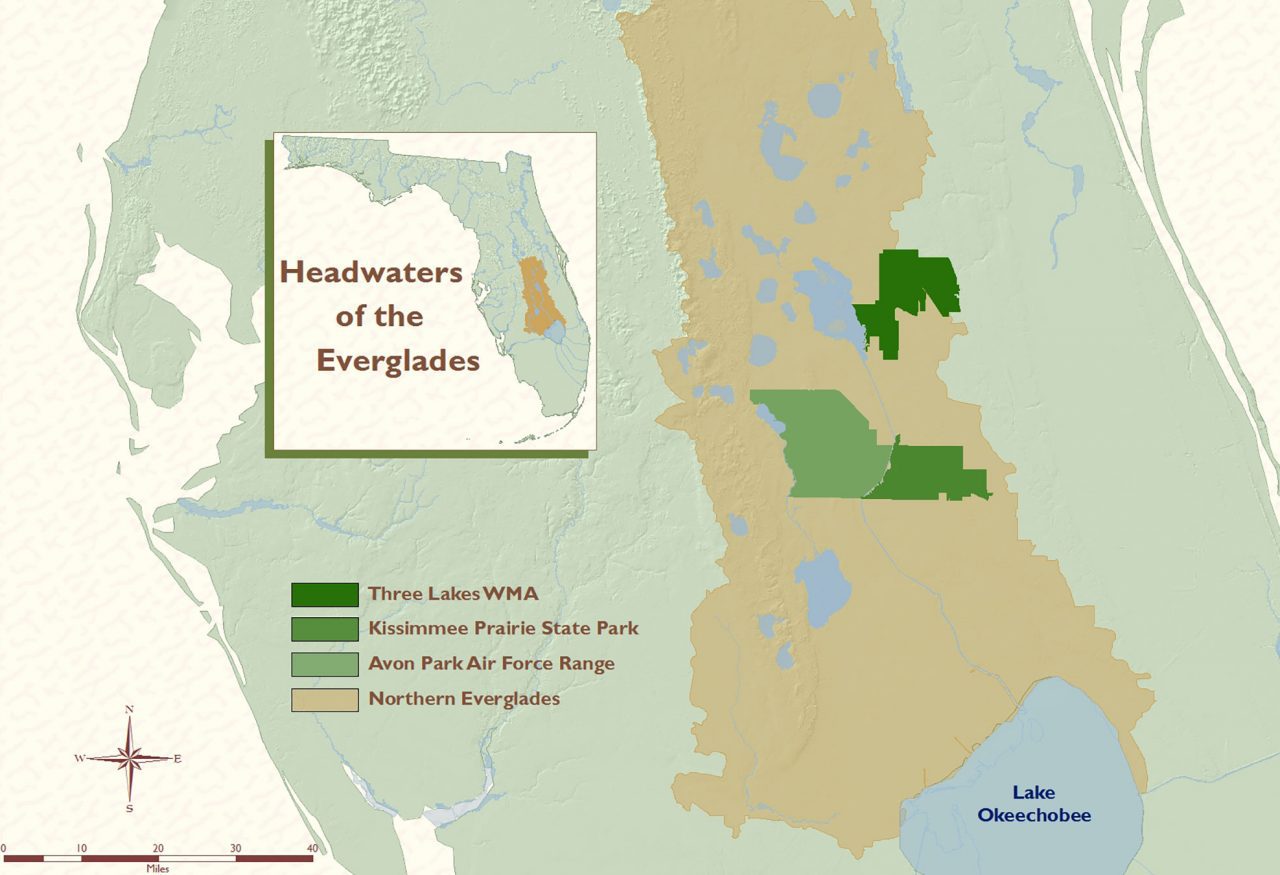

Florida dry prairie is within the headwaters of the Everglades, a mosaic of cypress swamps, pine forests, upland oak scrub, and grasslands. Less than 5 percent of the Florida dry prairie—the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow’s vital habitat—is left. The sparrows survive in only a few remnant populations in Florida.

Florida dry prairie, home to the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow.

The Florida dry prairie region lies within the headwaters of the Evergades.

Eastern Meadowlarks also live in dry prairie, and are another species in trouble.

The unique dry prairie region supports distinctive subspecies of other birds, including the Florida Burrowing Owl...

and the Florida Sandhill Crane.

The Decline

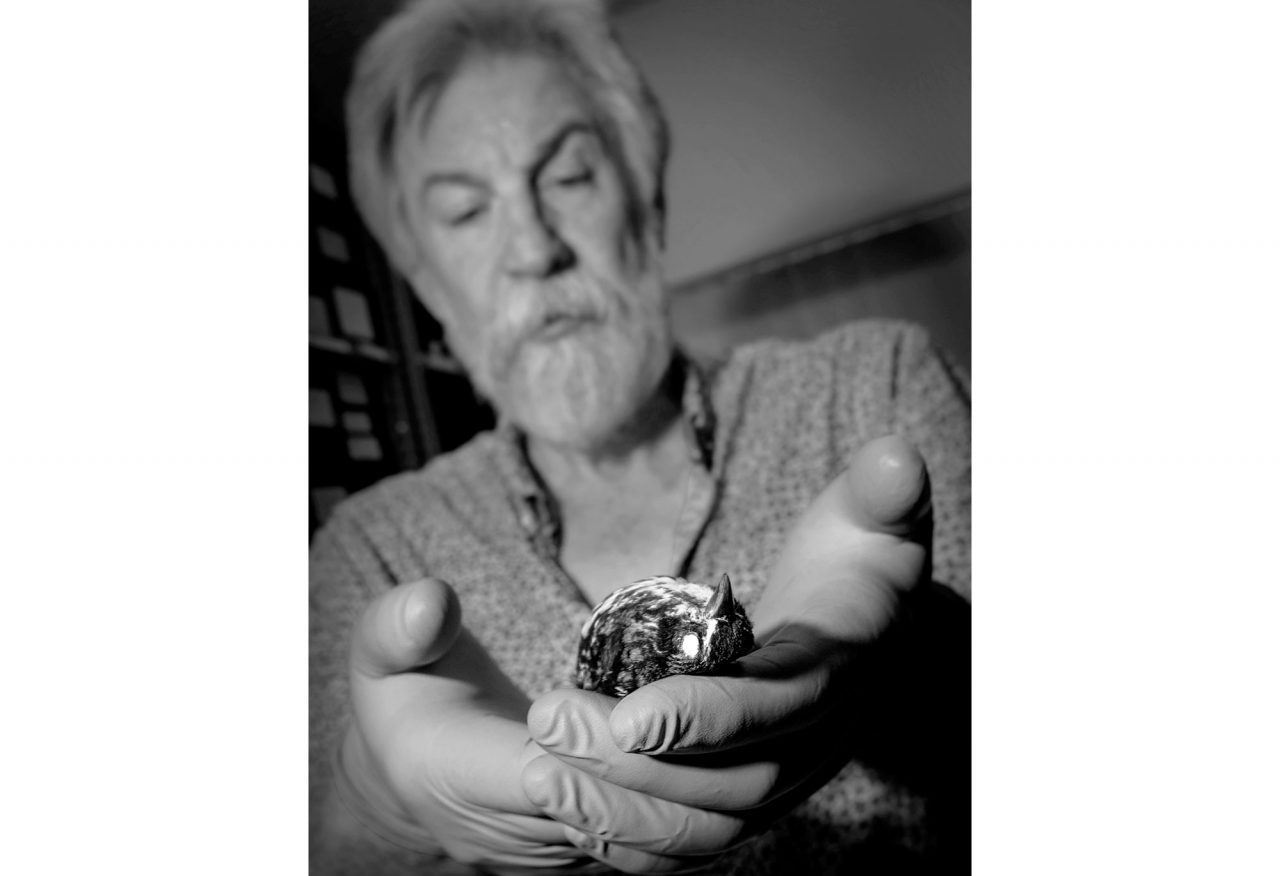

During the 20th century Florida saw the extinction of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, Carolina Parakeet, and Dusky Seaside Sparrow. A last-ditch conservation effort tried to save Dusky Seaside Sparrows in the 1970s. Captive breeding efforts were tried, but the bird still disappeared into extinction in 1987, a victim of habitat loss. The Dusky’s long shadow looms over current efforts to save the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow. Have scientists and conservationists learned enough in the last 30 years to save another imperiled Florida sparrow? Will society put that knowledge into action to save the bird?

Reasons for the decline include land uses as varied as cattle ranching, citrus growing, and clearing for housing developments, as well as predation by spotted skunks and—incredibly—the tiny, invasive fire ant.

In the late 1800s, large-scale land drainage for agriculture and development began in the northern Everglades. Much of what was once dry prairie is now pastures for cattle. Today, cattle ranchers play an important role in conservation by keeping land in grass rather than converting pastures into housing developments. But in the past dry prairie was drained and planted with exotic vegetation such as South American bahiagrass to create cattle pastures. These prairie-to-pasture conversions degraded the habitat quality of dry prairie.

And just in the last 75 years, Florida’s human population has dramatically increased from around 2 million to more than 20 million residents. Continued land development has fragmented the remaining dry prairie, which now exists in isolated habitat islands of conservation lands. Meanwhile, housing developments continue to expand and put pressure on Florida’s wildlands.

Citrus groves are almost synonymous with central Florida and the northern Everglades. Twice a year orange blossoms perfume the air of the region, but citrus has sometimes come at the expense of Florida’s birdlife. Many groves were planted on converted dry prairie that was likely home to Florida Grasshopper Sparrows in the past.

Dr. Reed Bowman of the Archbold Biological Station holds a specimen of the extinct Dusky Seaside Sparrow.

Much of what was once dry prairie in the northern Everglades is now pastures for cattle.

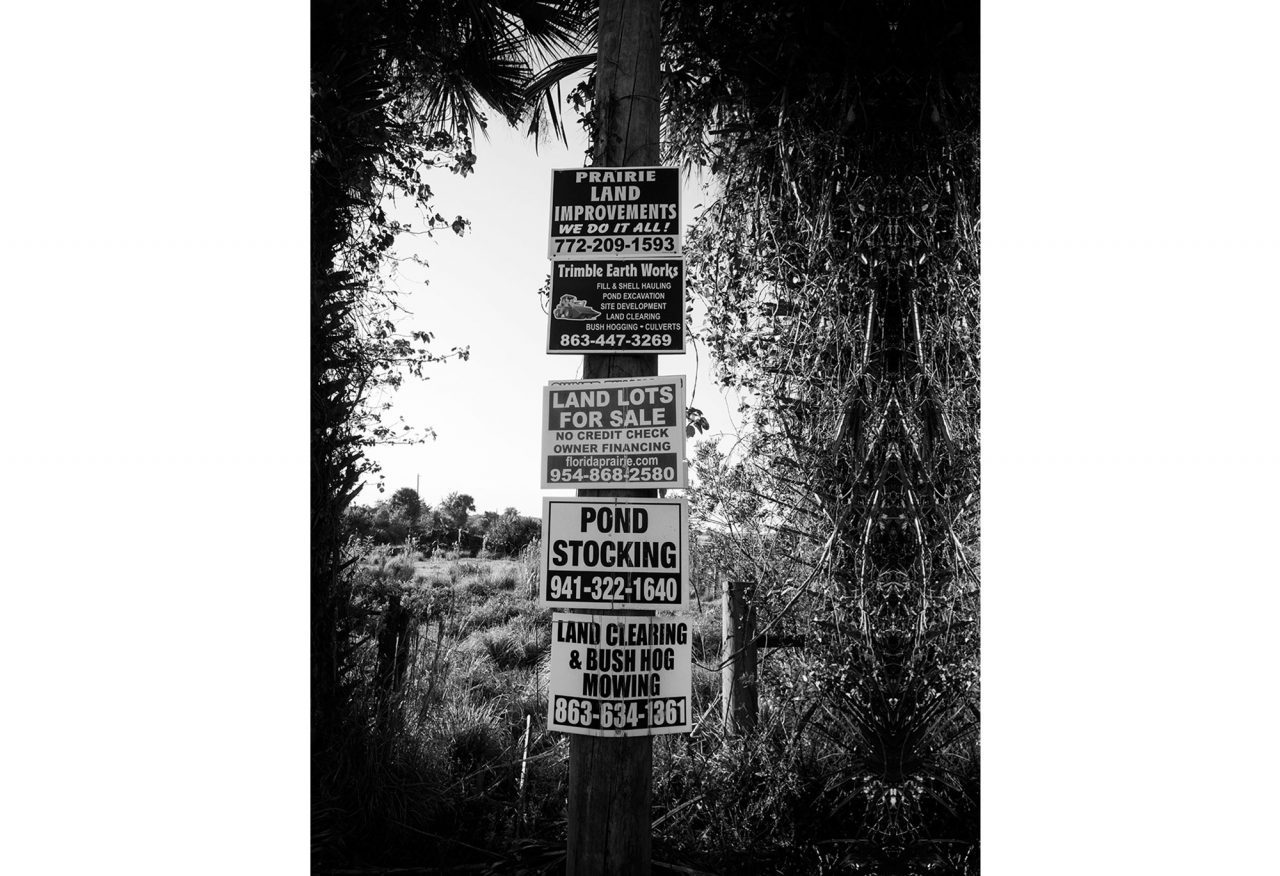

Florida's booming population also puts pressure on undeveloped land. For-sale signs are a common sight along the roads leading into Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park.

Twice a year orange blossoms perfume the air of the Northern Everglades. Sometimes citrus comes at the expense of Florida’s birdlife.

Some citrus groves are on converted dry prairie that was likely home to Florida Grasshopper Sparrows in the past.

Fire ants have spread throughout the dry prairies and are known predators of ground-nesting birds. Biologists have used boiling water to temporarily eradicate the ants near some Florida Grasshopper Sparrow nests.

Spotted Skunks eat eggs and chicks at Florida Grasshopper Sparrow nests.

Biologists are studying spotted skunk behavior in sparrow habitat to learn how to protect sparrow nests.

A scientist studying spotted skunk behavior.

Solutions

Habitat rehabilitation and management is critical if the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow is going to maintain a wild population. The entire population of wild Florida Grasshopper Sparrows is down to fewer than 150 birds. These last survivors of their species are closely monitored, and biologists use a number of approaches to ameliorate threats:

- Population monitoring: Using mist nets, biologists catch adults to check their health and use bands to track their survival.

- Nest protection: Biologists put up barriers to exclude predators and even rescue chicks from drowning in heavy rainstorms.

- Blood samples taken from adult Florida Grasshopper Sparrows tell researchers about the genetic and physiological health of the birds. So far, they have found no evidence of inbreeding, which can be a problem among small populations of endangered species.

- Prescribed fire removes trees that have encroached on the dry prairie and promotes the growth of native plants. It is a management tool used to mimic lightning-caused wildfires that were once common in Florida and played an important role in maintaining ecosystems.

- Captive breeding: After several years of consideration, and under the shadow of the Dusky Seaside Sparrow extinction (above), six Florida Grasshopper Sparrow chicks were taken from the wild in 2015 and brought to the Rare Species Conservatory in Loxahatchee. In 2016, additional eggs and nestlings were brought to the Rare Species Conservatory as well as the White Oak Conservation Center in Yulee.

Biologists use mist nets to catch adults, check their health, and band them.

Banding a Florida Grasshopper Sparrow.

The biologists also protect the nests with predator fences and even by rescuing chicks from heavy rainstorms.

Blood samples tell researchers about genetic and physiological health of the birds.

Prescribed fires help to mimic the effects of frequent lightning-caused fires that are a part of the dry prairie's natural system.

Captive breeding is a last-resort tool for saving species on the edge of extinction.

White Oak Conservation Center, in Yulee, is one of two sites where captive breeding is underway.

The Future

Will the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow make it through the 21st century? Or even the next decade? Prospects seem bleak, but there is reason for hope. More than 75 dedicated wildlife biologists in a working group have pledged not to give up. They continue to adapt and move forward with recovery plans. They cannot turn back the clock on the past 100 years of landscape changes, but through their persistence they seek to show that Florida can still make room for one of its smallest, most vulnerable birds.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you