A New Dawn for the Night Parrot

By Sarah Toner

June 12, 2017

From the Summer 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

“Next to the discovery of a new species, there is no event so exciting as the rediscovery of a lost one,” a biologist named Hugh Wilson wrote 80 years ago in a paper about Australia’s Night Parrot. At the time, there hadn’t been a confirmed sighting of a Night Parrot in 25 years, and despite his hopeful tone, there were to be no more sightings for the rest of the century.

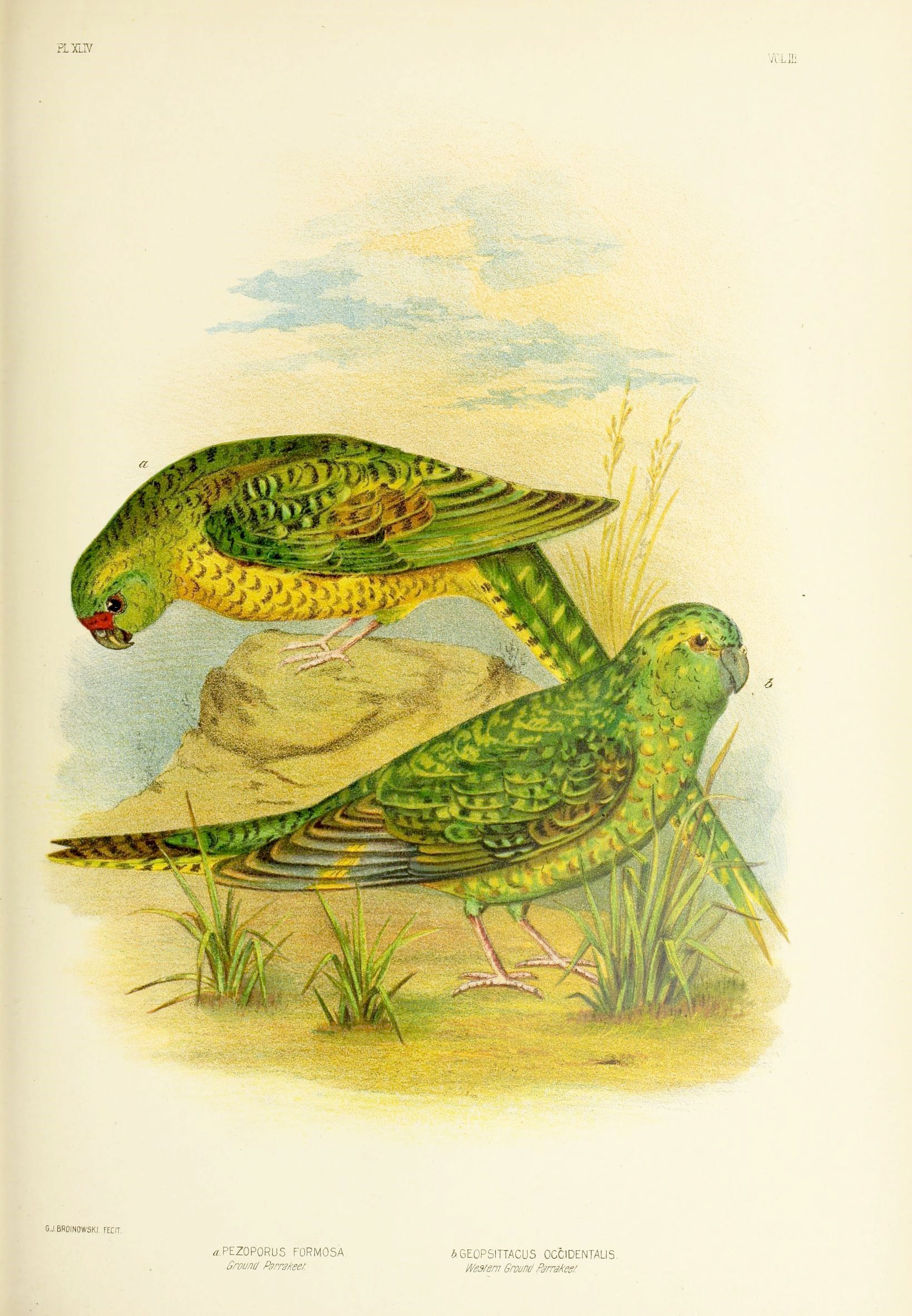

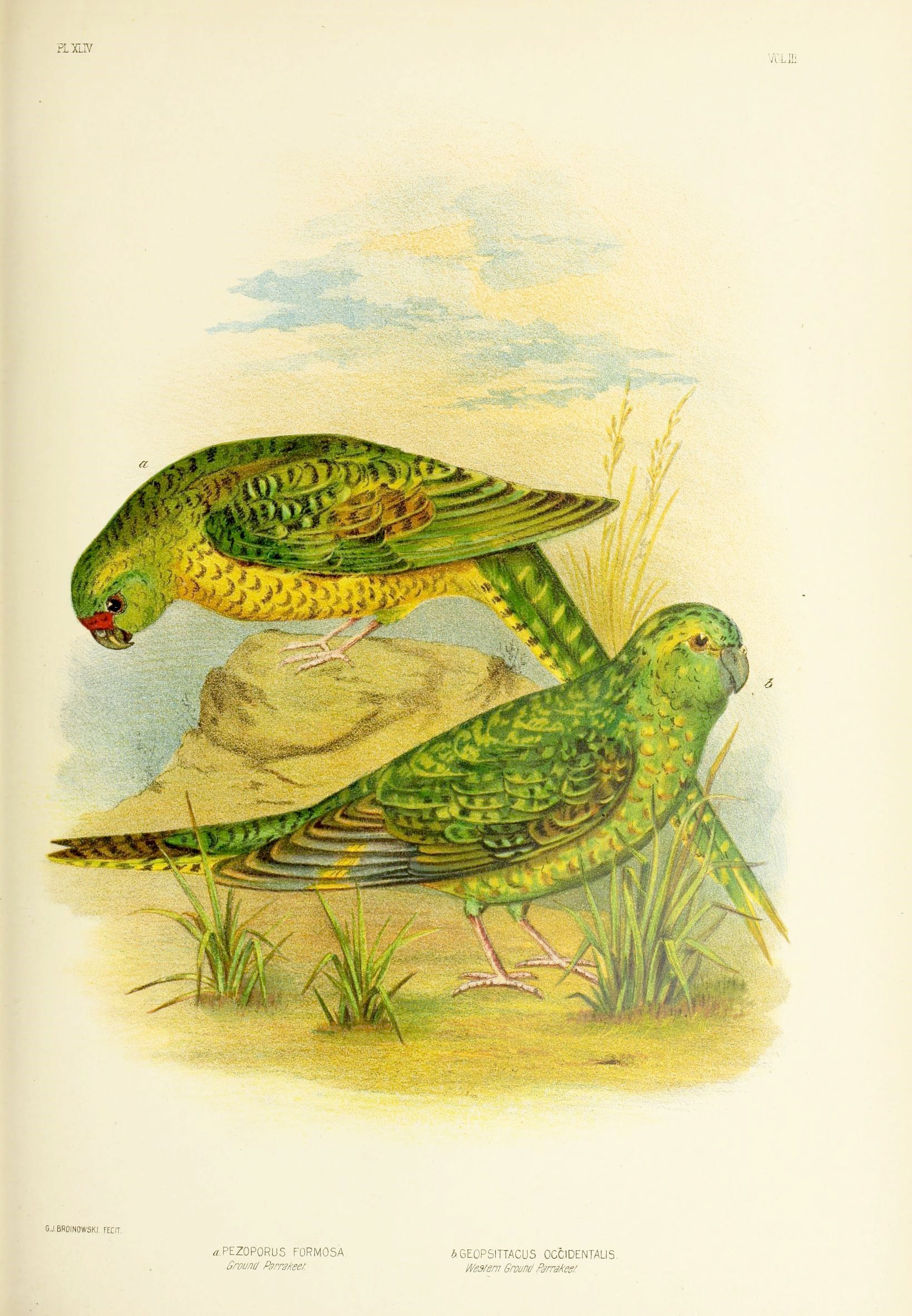

Even by the standards of Australian wildlife, the Night Parrot is an odd, almost fantastical creature. It’s a bright yellow-and-green parrot with big eyes and stubby legs that creeps through the driest regions of Australia beneath a spiky, almost impenetrable kind of grass called spinifex. It only comes out under cover of darkness. And until recently, no one even knew what it sounded like.

Night Parrots were recorded into the early 20th century, but Australia was changing. European settlement during the late 1800s brought invasive plants, predatory cats and foxes, and different fire regimes to the continent’s dry interior. Alongside many of Australia’s small desert mammals, Night Parrots drifted into extinction. Or so it seemed.

“If we had intentionally gone out and tried to make these things extinct, we couldn’t have done it better,” says Steve Murphy, a Night Parrot expert with the nonprofit Bush Heritage Australia.

Now, in just the last five years, a flurry of unexpected breakthroughs has changed the whole story. With two sightings on opposite sides of the continent, recordings of the bird’s call, a better understanding of their habitat, and even the discovery of a nest, a new view is emerging of this enigmatic bird.

Hope for the Night Parrot started to return in 1990, when a group of ornithologists stopped to bird along a remote highway in western Queensland. They happened to pull up beside a pile of feathers that turned out to be a roadkilled Night Parrot, a tantalizing confirmation that somehow, somewhere, a population endured.

Inspired by their story, a birder named John Young spent 15 years searching for that population. In 2013 his persistence paid off: he discovered Night Parrots in remote southwestern Queensland, the first living birds recorded in over a century.

Young had heard unfamiliar calls that he suspected were Night Parrots in 2008, but it still took five years before he successfully called a bird into a spotlight to get photo documentation. After his discovery, Bush Heritage Australia, state and federal governments, and scientists swung into action, protecting the location through a secret reserve known as Pullen Pullen and forming a Night Parrot Recovery Team.

Young’s audio recordings were kept under wraps to protect the few known birds, and only released in February 2017 to aid searchers in other parts of Australia (playback is still banned around Pullen Pullen). The hope was that birders equipped with the calls would be able to find new Night Parrot locations.

The very next month, 1,200 miles away from the Queensland site, four birders discovered a second population. “It was all very surreal,” says Nigel Jackett as he recalls flushing the first Night Parrot seen in Western Australia in over a century. For Jackett and his fellow birders, it was the culmination of a seven-year search that had begun even before Young’s discovery in Queensland.

More On Birds Coming Back From the Brink

Despite the timing, Jackett says the Queensland recordings didn’t help the group so much as confuse them. They heard strange calls, but “they didn’t really match the quality of the released calls… there’s definitely some sort of regional dialect,” he says. Instead, Jackett says their success lay in their understanding of Night Parrot ecology, pieced together from historic accounts and recent, undocumented sightings from a team led by Neil Hamilton of the Department of Parks and Wildlife in Western Australia, along with Tegan Douglas and Aneta Creighton. Traditional Martu landowners from the Matuwa/Kurrara Kurrara Indigenous Protected Area were also key collaborators.

With help from Hamilton, “we figured out that what these Night Parrots are likely to live in is very old spinifex,” Jackett says. “Once we tried that, it was actually the very first place where we found them.”

Ancient spinifex hummocks—some nearly 90 years old—are uncommon in Australia. Most were eliminated by massive fires fed by years of fuel build-up from European settlers’ fire suppression, leaving barely any old spinifex to shelter Night Parrots. Cats and foxes preyed on any parrots that were left, along with many of central Australia’s native mammals.

“Basically, if you’re a mammal [or a Night Parrot] in central Australia about the size of a rabbit, you’re either extinct or critically endangered,” Murphy says.

Despite these pressures, Night Parrots seem to have persisted in areas that managed to resist the changes. In the so-called “Channel Country” of southwestern Queensland, bare patches of rock surround spinifex hummocks, keeping them safe from fires. In Western Australia, networks of dry salt lakes, with soil too alkaline for plants to grow, serve a similar function. Better yet for the parrot, foxes are rare in both areas.

So if their habitat didn’t completely vanish, how did two different populations go unnoticed for a century? Hamilton thinks Night Parrots and other aridland birds and mammals have rebounded thanks to long-running restoration efforts. These include work to remove introduced cats and keep out spinifex-eating cattle and camels. Add to that a stroke of luck in the form of recent heavy rains, which cause spinifex to bloom and spur the parrots to call more frequently as they scramble to begin breeding, Hamilton says.

Jackett’s team made their discovery in the remote Australian outback in Western Australia, where the population density is 300 times lower than Wyoming, the least populated U.S. state.

“Where Night Parrots live is probably a thousand kilometers from any capital city, and it’s really a hostile place,” Jackett said. “You need to be fully self-sufficient. Where we were going, if it rained, we would have been trapped there for potentially a week.” On their expedition, the group traveled with a week’s food and water, a generator, and a backup vehicle.

Now that Night Parrots been found in two widely separated places, Jackett believes the birds may live on in other remote areas. “I think they’ve just been overlooked due to lack of knowledge about their ecology,” he says. “I think figuring out this habitat, a lot more birders are going to have the confidence to look for them in the right way.”

Murphy concurs: “One of the places that always jumps out at me is northern South Australia.” [Update: Researchers discovered evidence of Night Parrots living in South Australia in September 2017.]

While they’re still anything but common, there’s a good chance that more Night Parrots are out there in the Australian outback, foraging by moonlight in ancient riverbeds and slumbering by day in the thick, spiny protection of spinifex.

Sarah Toner is a Biological Sciences major at Cornell University (Class of 2019) and current president of the Cornell Student Birding Club. Her work on this story was made possible by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Science Communication Fund, with support from Jay Branegan (Cornell ’72) and Stefania Pittaluga.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you