What Does an Eclipse Sound Like? In 1963, We Found Out

By Marc Devokaitis

August 18, 2017

“The shades of night which accompany an eclipse of the sun have always intrigued mankind and caused him to pause, if only for a moment, to contemplate the mystery, the magic, the grandeur, and the extent of the universe of which he is a part.”

That’s the kind of sentiment that is drawing thousands of people to the path of the 2017 eclipse—but the words were written in 1963, by Peter Paul Kellogg, a professor of ornithology and bioacoustics at Cornell. And it’s what drew him to Maine for that year’s total eclipse, at 5:30 p.m. on July 20. Many people had come to Maine to see the eclipse, but Kellogg was there to listen, and to record bird songs.

As one of the pioneers of modern bird sound recording, it was natural that Kellogg was interested in capturing the vocal behavior of as many birds as possible during this rare occurrence. It was the first such total eclipse visible in the U.S. since 1932, and the first time wildlife recording technology was really up to the challenge of recording in the field. Yet he did his best to keep his expectations in check, writing:

“The eclipse does not influence many of the factors which affect bird song such as time of year and the physiological condition of the bird,” he wrote in the 1963 issue of The Living Bird. “It is also probable that the sudden interruption of an established diurnal routine is more confusing to some species or individuals than others. All these possibilities for variation in cause and effect…tend to keep the value of any observation a strictly local affair.”

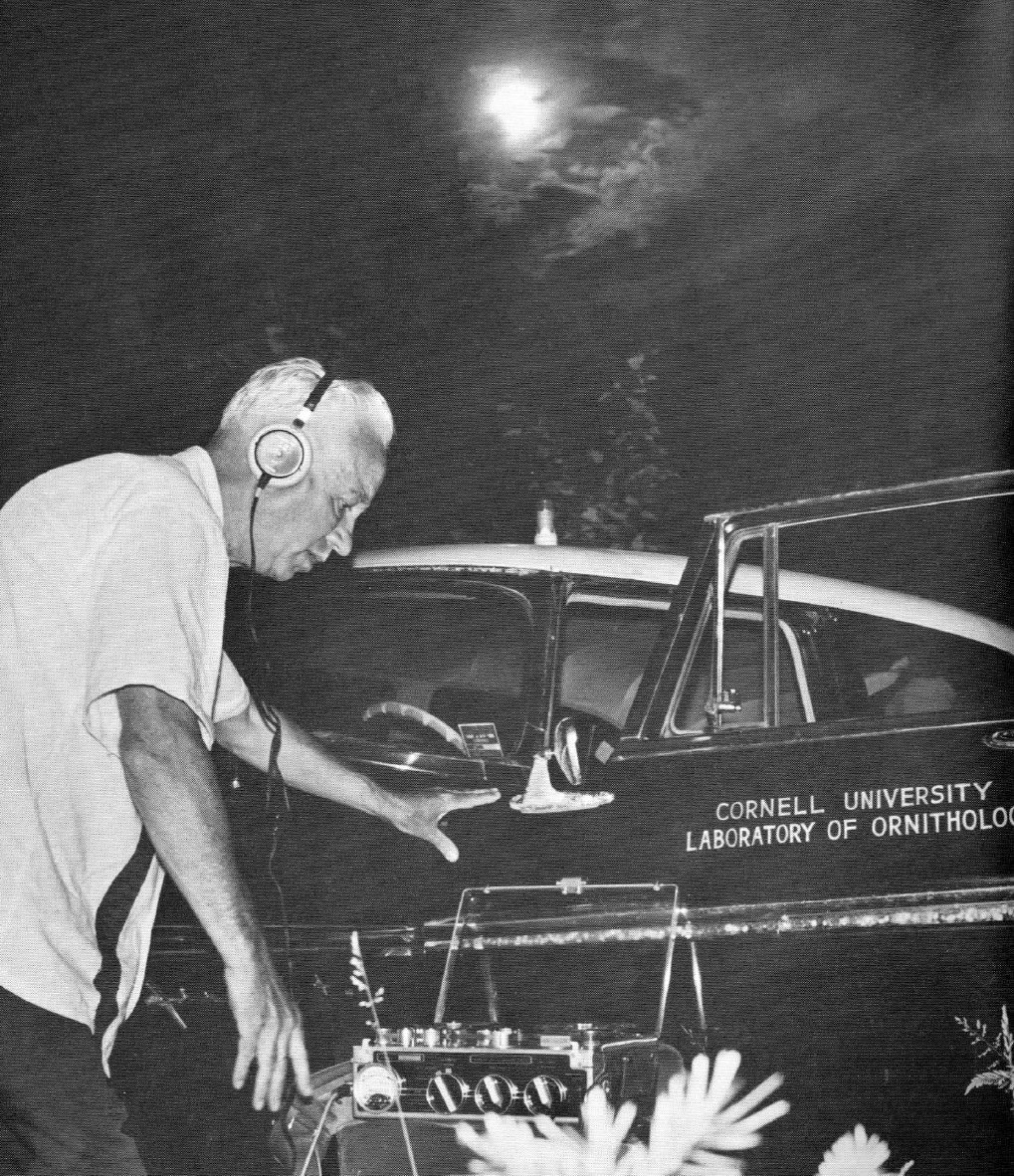

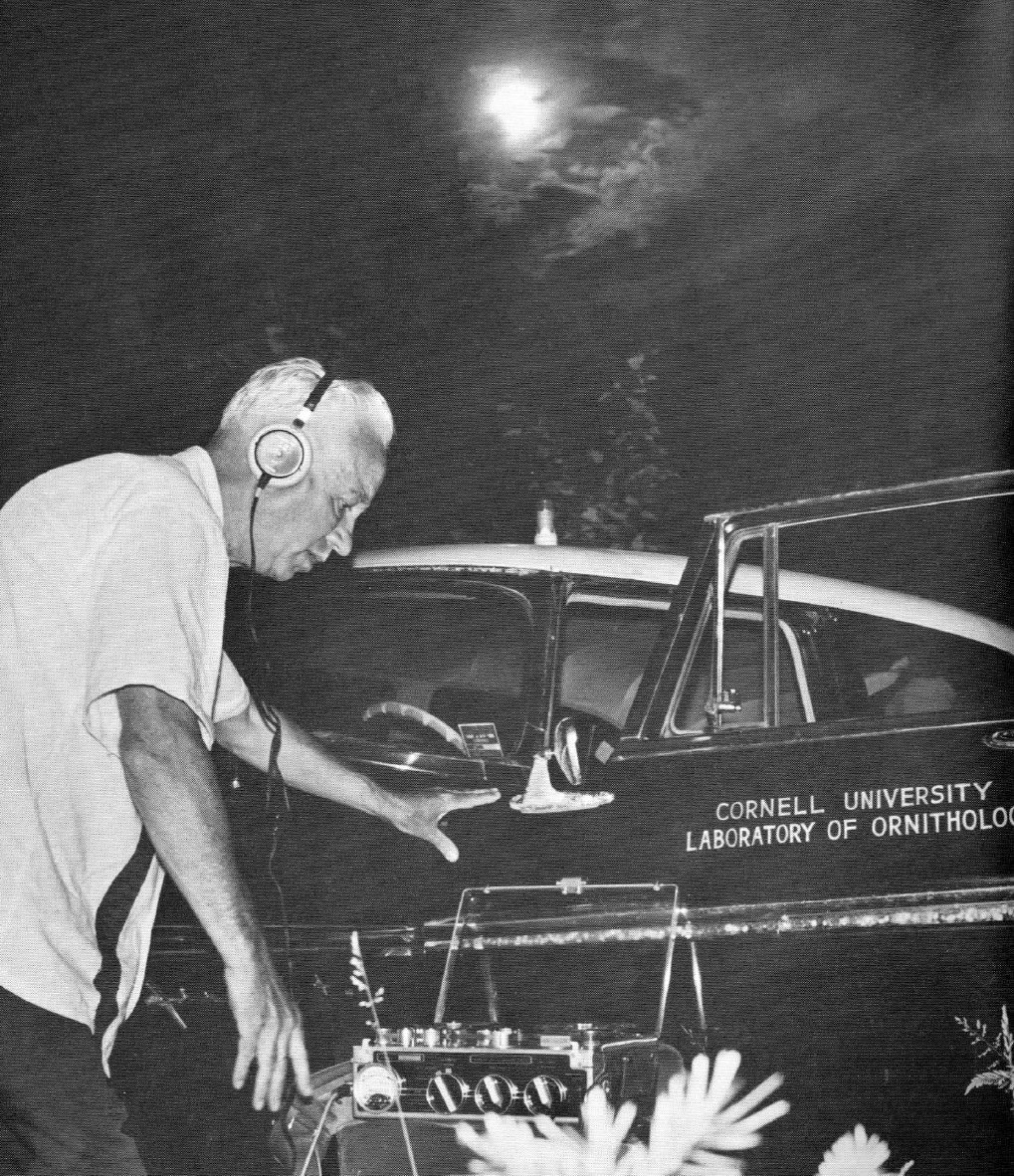

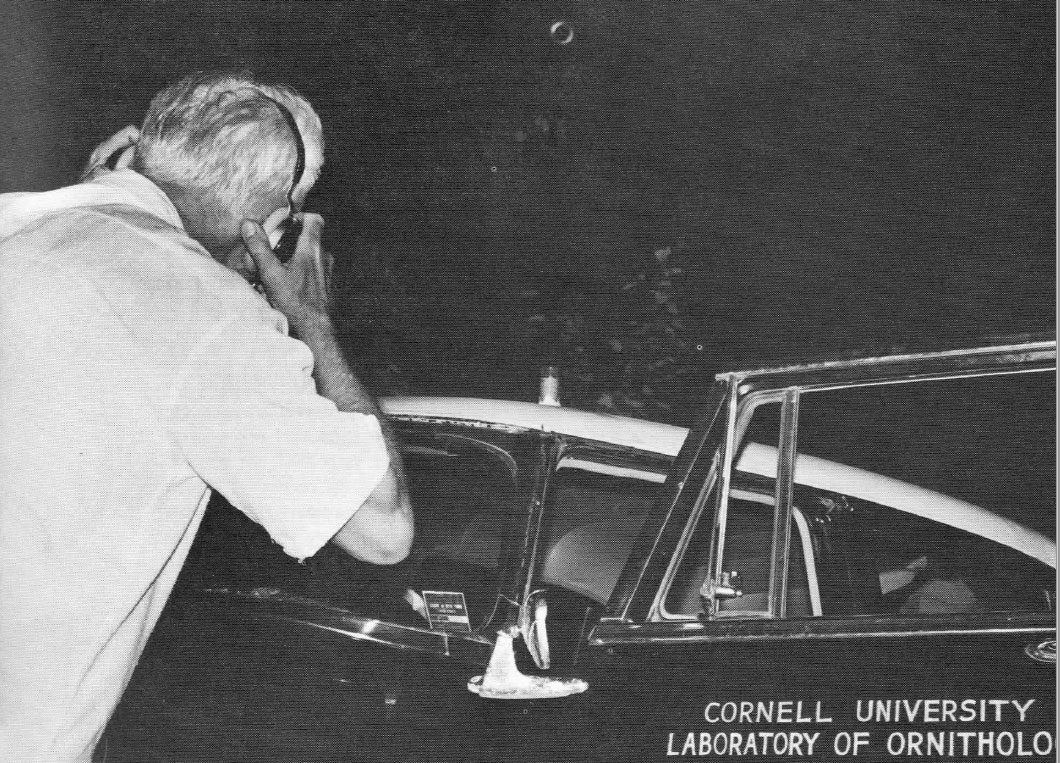

Nevertheless, as the event approached, Kellogg and colleague Calvin Hutchinson prepared. A local hunter described a promising patch of woods near Corinna, Maine. The pair drove their field vehicle, a 1950s sedan with “Cornell University Laboratory of Ornithology” hand-lettered on the door panel, down an old logging road and set up in a forest clearing.

A late afternoon in midsummer might not seem optimal for capturing bird song, but before the eclipse began the pair noted classic Maine woods birds such as Olive-sided Flycatcher, Hermit Thrush, Swainson’s Thrush, Veery, Myrtle [now Yellow-rumped] Warbler, Slate-colored [now Dark-eyed] Junco, White-throated Sparrow, Red-eyed Vireo, and American Goldfinch.

“When totality comes,” Kellogg wrote, “one gets more the impression of turning off a light rather than that of the gradual and normal twilight… more of a shock than we are accustomed to experience at dusk.” Totality lasted for about a minute, although Kellogg noted that his eyes took long enough to adjust to the darkness that it felt more like 20 seconds in all.

“As the darkness descended, bird song fell off noticeably but some species, according to our recordings, never did stop completely.” he wrote. “The per-chic-o-ree of the Goldfinch was heard clearly in the middle of the totality; the Hermit Thrush and Swainson’s Thrush sang weakly during the darkness; a Veery called.” Despite the short period of darkness—about twice the brightness of a full moon, he wrote—no Eastern Whip-poor-wills took the opportunity to sing. After the light returned, the first call was a spring peeper (frog), and then a White-throated Sparrow, a Hermit Thrush, and a Swainson’s Thrush.

Not knowing what to expect, Kellogg had opted for a directionless microphone rather than a parabolic. It allowed him to capture songs from all around, but yielded poorer recordings than he could have gotten by pointing a parabolic mic at a singing bird. “The results of our recordings are somewhat disappointing if viewed only from an entertainment point of view,” he wrote. “Perhaps the most profitable results of our brief expedition were some ideas as to how to conduct such a study in the future.” Among his tips:

- select an area “known for its quietness and abundance of bird life and song”

- watch, listen, and record in the area for at least a week before the eclipse

- use a light meter and compare sounds heard during the eclipse with singing under similar light levels at dawn and dusk on the day before and day after the eclipse

“Such a study, requiring both time and care, would presumably have to be done by enthusiasts rather than by paid observers,” Kellogg noted, in a nod to the field that would emerge over the next 50 years and become known as citizen science. Kellogg himself compiled a few reports from bird watchers elsewhere in New England: calling Common Nighthawks, White-throated Sparrows, and Swainson’s Thrushes near Mt. Katahdin; and a group of gulls near Marblehead Neck, Massachusetts, that took off for their roosting sites, only to turn around as soon as the light began to fill back in.

Just as Kellogg anticipated, in 2017 possibilities for joining in abound. Help study the eclipse using these eBird suggestions or by joining in with the California Academy of Science and iNaturalist.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you