In the Aerie of the Philippine Eagle

By Greg Breining

Photo by Kike Arnal. September 18, 2017From the Autumn 2017 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

It was the same grueling routine, but of course Neil Rettig was a senior citizen now—at 63, a good three decades older than he was in 1977, when he first climbed into the tops of 100-foot trees in the Mindanao jungle to photograph the Great Philippine Eagle.

His support crew in this century had better gear and safer techniques. But still.

Every morning at dawn, Rettig strung a climbing rope into the uppermost branches, climbed into his harness, hitched himself to the rope, and climbed like an inchworm—a foot at a time, brow sweating and arms burning—until he hoisted himself onto a cramped platform of boards screwed into the tree, and wriggled himself into a camouflage blind.

The crew had started on a hillside 97 yards from the eagle’s aerie, a heap of sticks tucked above a big knot of epiphytic plants so wrapped in vines and foliage that it was nearly invisible from the ground. The length of a football field was close enough for shots of eagle parents soaring through the forest canopy and flying into the nest, but still too distant to capture this majestic raptor’s personality and intensity.

Day by day, tree by tree, Rettig and his crew hoisted themselves above the ground and built new platforms, each incrementally closer than the one before. Each time they dreaded the thought that this might be the effort that would scare the parents from the nest, with the risk that they would abandon their single chick. But they were convinced it was a risk worth taking if they were to produce new film footage of one of the world’s rarest birds.

And that was the aim of Rettig’s return—to recapture the regal Philippine Eagle in all the majesty of today’s Ultra-HD film technology, to give Filipinos the most intimate look ever at their national icon, to peer right down into the nest and see the glint in the eyes of newly hatched chicks.

“I think the closer we can get to the eagle family, the more intimately we’re going to bring in the viewer and move people in the end,” Rettig explains. “And I think that’s really important, because we want to sway people. We want people to look at these images and say, yes, we have to save the Philippine Eagle.

Finally, they began work on a blind just 20 yards from the nest, hauling lumber up to the treetop, fastening a few boards in place, and then climbing down after an hour so the parents would return to the nest. It took days of intermittent labor, but at last the platform was complete. And best of all, when Rettig and his crew returned to the ground, the eagles returned. The crew was jubilant, smiling and slapping high-fives.

At daybreak, Rettig inched his way back up the tree and settled into his blind. He remembered how much fun this was, perched above the world in a wilderness of tree limbs he shared with eagles, an airy aerie of his own. He switched on his video camera. The telephoto lens put the adult eagle right in his lap, filling his viewfinder with its flamboyant pompadour of variegated feathers.

“When a Philippine Eagle looks right in your eye and makes eye contact it’s breathtaking,” Rettig says. “The crest flares up, those light eyes, those beautiful bluish eyes stare right at your eyes and that contact is riveting, powerful. They’re magnificent, they’re splendid, you know. It’s truly, truly a unique creature.”

The Power of Film Tells a Critical Conservation Story

Neil Rettig is an internationally renowned wildlife filmmaker who has worked for National Geographic, IMAX, and the BBC over a 40-year career built on the daring and difficult task of trekking into jungles for mountain gorillas, jaguars, Harpy Eagles, and—the Philippine Eagle.

He first traveled to the Philippines with two high school chums in 1977, having never seen the eagle or the country. On the insurrection-wracked island of Mindanao, the young men searched the rugged countryside for nests. Then for hundreds of hours they sat in treetop photography blinds and watched as Philippine Eagles hatched their eggs, raised their chicks, and hunted prey.

The payoff after a year and a half: a stockpile of 16-mm footage that stretched four miles, including breathtaking scenes, never filmed before, of a bird the world barely knew. Besides anchoring a feature story in National Geographic magazine, the images were made into films in three languages and donated to the local Philippine Eagle Foundation, which used them to spread the word about the plight of the eagle and its forest habitat.

“I think our original project and our original films may have bought the eagle time,” says Rettig. Over his four-decade, globe-trotting career, the striking intensity of the Philippine Eagle never left him. He always wondered if there would be an opportunity to update his work on the eagle—to capture new footage for conservation and do more to foster the love of Filipinos for their national bird.

In 2012, Rettig was back in the Philippines on assignment from National Geographic to film monitor lizards, and he took his wife, Laura Johnson, to see a captive Philippine Eagle in the Manila zoo.

I didn’t want to waste the last years of my life just sitting at home in retirement, when I could still climb a big tree. I wanted to go out and do something.~Neil Rettig

Johnson began to cry.

“They are the most regal, incredible creatures in the world,” she says. “We both got really emotional and decided we really have to try to make something happen again, knowing that the eagle is really critically endangered.”

“I vowed right then and there,” says Rettig, “I’m going to return to the Philippines.”

Back in the States, Rettig broached the subject of funding a second trip to the Philippines with longtime friend John Fitzpatrick, director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

“We just jumped,” says Fitzpatrick. “What better way to tell that story than to use an iconic top predator as the symbol of that forest? That’s what makes it an especially gripping and important conservation story. It’s not just saving the eagle. The eagle represents the entire future of the tropical forest of the Philippines.”

The Cornell Lab joined forces with Rettig and the Philippine Eagle Foundation—based in Davao City—on a conservation media initiative to tell the eagle’s story anew to Filipinos everywhere, from the most remote jungle villages to the highest levels of government.

The foundation was a key partner. The only conservation group that’s fully focused on the species’ conservation, the Philippine Eagle Foundation is breeding captive eagles; rehabilitating and releasing injured birds; and employing biologists and local “forest guards” to research, track, and protect the few eagles that remain.

Director Dennis Salvador says the foundation was on board from the beginning: “We think it will provide prestige and credence to what we do, but more importantly, elevate the status of and the plight of the eagle to where it should be.

“That’s on top of the world’s list of most endangered birds.”

So in 2013, Rettig returned to Mindanao to film one more massive eagle project before his body would no longer tolerate the abuse of climbing trees and swarms of insect pests.

“I knew the job wasn’t done,” Rettig says. “Producing new, beautiful images of the eagle could go a long way for conservation.

“I didn’t want to waste the last years of my life just sitting at home in retirement, when I could still climb a big tree. I wanted to go out and do something.”

The Ultimate Forest Predator

The Philippine Eagle is one of the largest eagles in existence, with a wingspan of 7 feet and the weight of a large female approaching 20 pounds. It has a greater length and wing surface than the Harpy Eagle and Steller’s Sea-Eagle.

It occasionally soars on thermals above the tropical forest, but the Philippine Eagle makes its living by diving and dodging through the forest canopy. Once called the “Monkey-eating Eagle,” it indeed does eat monkeys, but also flying lemurs, squirrels, civets, hornbills, and bats. It even stalks the forest floor like a winged velociraptor, snatching up lizards and snakes. Rettig has seen it clasp a tree trunk with its wings and use its talons to pluck prey out of a nesting cavity.

Jayson Ibanez, a Philippine Eagle Foundation biologist, says the Philippine Eagle is the ultimate forest predator, exquisitely designed by nature: “It has this magnificent crest of feathers, which it uses as a satellite dish to hone in on its prey. And as it hones in, it moves its head sideways. It’s like, I don’t know, zooming in on its prey. Then it flies silently across the forests, like a thief, surprising prey.”

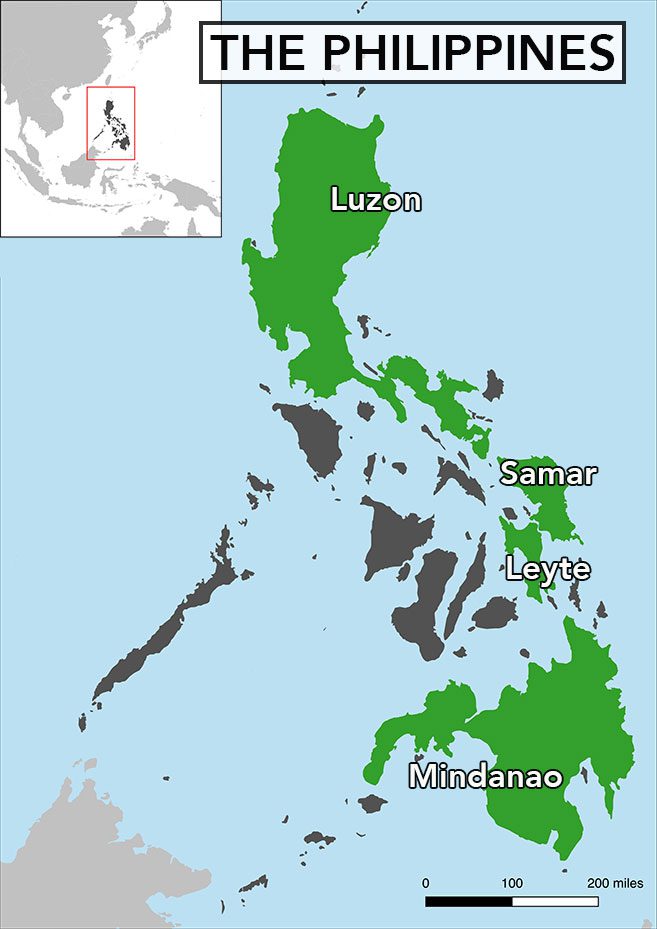

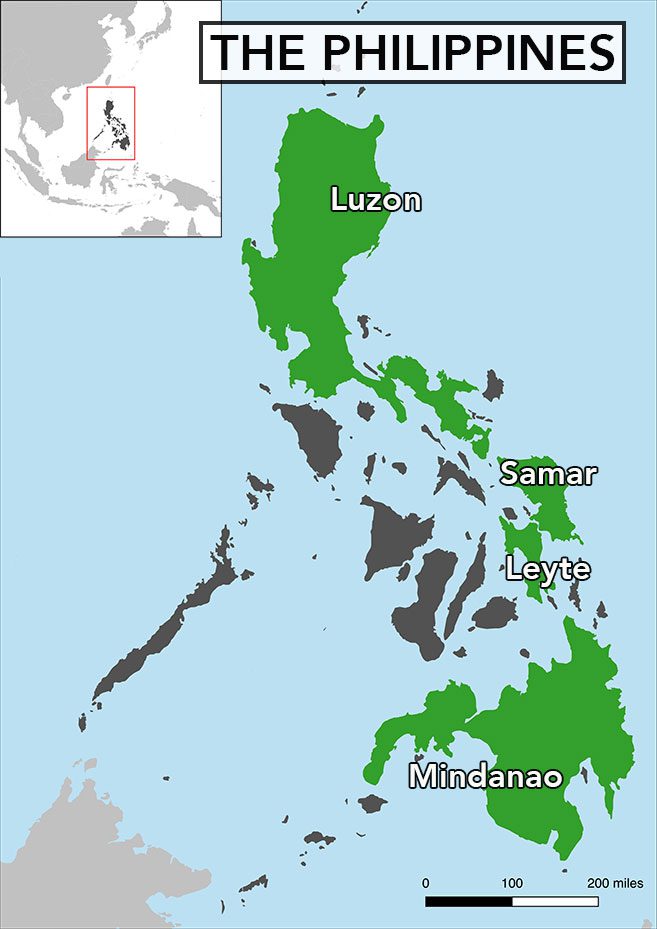

The eagle was unknown to Western science until it was reported by English naturalist John Whitehead in 1896. Since then, it has been found on only four islands—Luzon, Samar, Leyte, and Mindanao.

Purely a bird of the forest, the Philippine Eagle’s range once covered 90 percent of the Philippines. During nearly four centuries of Spanish rule and another half-century of U.S. colonization, the forests shrank. Logging accelerated as Japan imported wood to rebuild from the destruction of World War II. Then the regime of Ferdinand Marcos dispensed logging contracts as patronage, and heavy trucks carried logs from the forest day and night.

Marites Dañguilan Vitug, author of Power from the Forest: The Politics of Logging, says that “before all the massive logging that took place, primarily in the 1960s and 1970s, we had some of the most diverse forest ecosystems on the planet. From something like 70, 80 percent forest cover, we’re down to less than 20 percent.”

As lowland forest disappeared, eagles lost nesting sites and, more vitally, prey. The eagle’s range contracted to higher, more rugged terrain as loggers cut the lowlands. In 1965, Dioscoro Rabor, a noted Yale-educated Filipino zoologist, announced that the bird was in rapid decline. Soon after, the government established the Monkey-Eating Eagle Conservation Program. The effort really found its footing in the early 1970s with the arrival of several Peace Corps volunteers who worked with the government’s Parks and Wildlife Office.

One of the volunteers was Robert Kennedy, a graduate student from the College of William & Mary who first became acquainted with the Philippine Eagle at an American Ornithologists’ Union meeting in Buffalo, New York.

“This mounted specimen was in a corner of the museum and it was kind of like love at first sight,” says Kennedy. “The rockets went off, the whole thing. I said, ‘Okay this is what I want to study.’”

Kennedy helped the Philippine government survey the remaining population of eagles on the southern island of Mindanao in 1972–73, but a Muslim-Christian civil war forced him to leave. When he returned to the islands in 1977, Kennedy brought with him Neil Rettig, Wolfgang Salb, and Alan Degen. The three young men had recently filmed Harpy Eagles in South America. With a grant from National Geographic, Kennedy and the three filmmakers took off for Mindanao to make films of a rare, never-before-photographed eagle.

“That’s where it all started,” says Rettig, “this obsession with the Philippine Eagle.”

But first they had to find a nest. And a nest hadn’t been seen in years—at least by anyone in the government. Kennedy, Rettig, and the team split up to different parts of the island and found a nest in a remote jungle corner of Mindanao. Then they began spiking up nearby trees, hauling lumber into the canopy, building platforms, and filming.

They climbed up every day at dawn and endured torrential rains and clouds of bugs. Gnats pasted themselves to their eyelids. Hours passed when nothing happened.

Then one day Rettig noticed the female eagle began to shuffle on the nest. As she moved, Rettig spotted the egg beneath her cracking open.

Rettig and his assistants kept the film rolling as the chick grew. Every 10 days Kennedy climbed the tree and into the nest to weigh the chick. These were perilous visits. Once an eagle attacked, leaving a deep gouge in Kennedy’s motorcycle helmet. Even so, all was going to plan.

Then, when the chick was 27 days old, a catastrophe. As Rettig was filming, the chick refused morsels from its parent. It began shaking its head violently, gagging for several minutes. In a series of spasms, it died. Something, perhaps a bone, was lodged in its throat.

“The whole project fell apart,” Rettig recalls. “We went back to Davao, to our house, and we just sat there. What are we going to do next, you know?”

Then more disaster. Armed guards at the airport X-rayed the crew’s film of the chick. The only footage in existence of a Philippine Eagle nest was shot through with electromagnetic waves.

“It looked like the aurora borealis in every frame. Just curtains of light,” says Rettig. “That X-ray mishap probably destroyed three weeks of some of the rarest footage we got on the whole project.”

Still, Rettig and his team regrouped and carried on to look for another nest. After two months, they found one after tagging along with loggers on Mindanao.

“Because that’s where we could find eagles, in the forest that they were intending to cut,” says Rettig.

The eagle was nesting in a lauan tree marked with a blue X. A road had been cut right up to the tree. Machinery and bulldozers were staged to cut it.

“We were desperate,” says Rettig. “This was the perfect nest for filming.”

Rettig and Kennedy talked to the head of the logging company. Not only would he spare the tree, he said, he’d set the area aside as a sanctuary.

Then the government got involved, and it overreacted, expanding a no-cut zone around the tree to 2 kilometers and forcing farmers off their land.

“So all of the families, some of these were traditional peoples who had lived in those mountains from the beginning of time, they were going to lose their ancestral properties and everything else,” recalls Kennedy. “Well, they justifiably became angered. And who is responsible for this but a guy named ‘Bob Kennedy’. Right away there was a price on my head.”

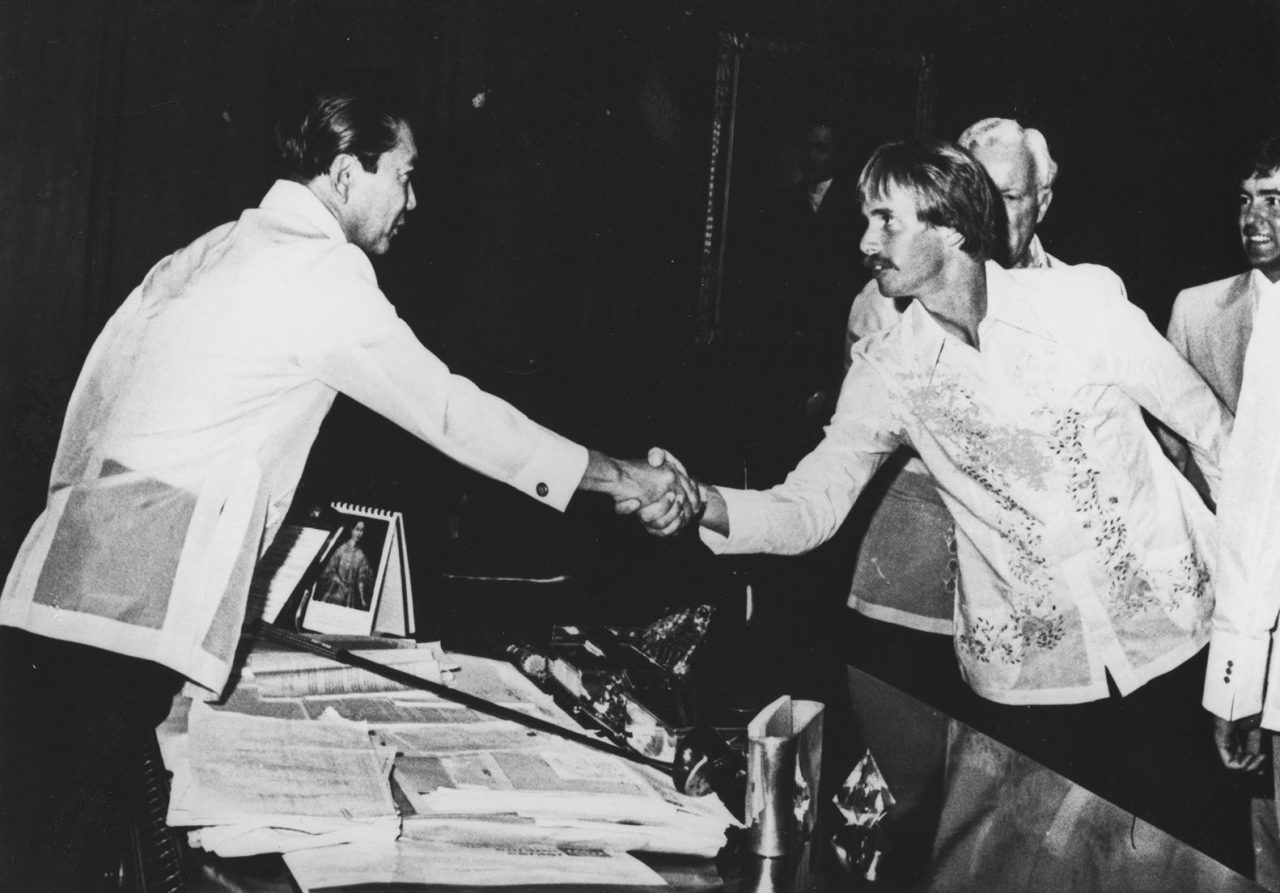

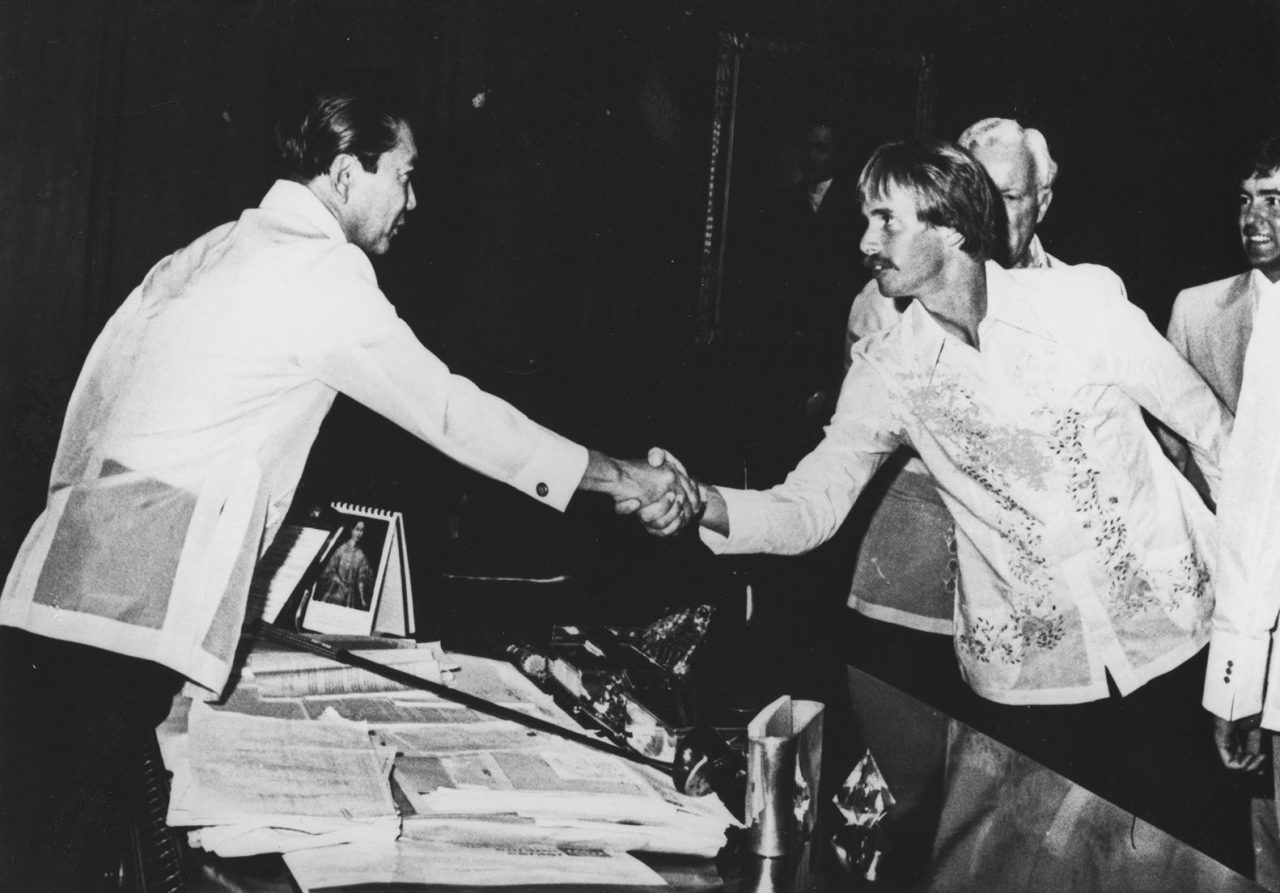

Kennedy went directly to President Marcos and convinced him to allow the people back on their land, which made it safe for the filmmakers to go back to work. Despite Marcos’s reputation for corruption and destructive logging, the Philippine president was a strong supporter of the filming effort in the late 1970s. After one crucial meeting with Rettig and Kennedy at the Malacañang Palace, Marcos renamed the “Monkey-eating Eagle” as the Philippine Eagle, an eminently more honorable moniker. Marcos also proclaimed the eagle to be the national symbol. Today, the Philippine Eagle appears on the nation’s currency, and it’s an emblem for many units of the Philippine Air Force.

Kennedy and Rettig left the Philippines in 1979 with exhilarating photos and film of Philippine Eagles flying, hunting, nesting, and caring for their young. The first film they completed, in 1981, has been shown to Filipino school kids and communities for more than 30 years. Rettig also produced a film about the eagle for the BBC.

Kennedy wrote “Saving the Philippine Eagle” for the June 1981 issue of National Geographic, illustrated with photography from the three cameramen. Kennedy climbed the tree and into the nest to weigh the chick. These were perilous visits. Once an eagle attacked, leaving a deep gouge in Kennedy’s motorcycle helmet. Even so, all was going to plan.

“At that time, National Geographic had a circulation of 10 million people. You could go to remote places of the Philippines and they could hardly afford food, but somebody in town had a subscription to National Geographic,” says Kennedy.

“And that film alone was so popular in the Philippines that one of their famous newspaper editors or editorial writers, he was so moved by that film that he urged all the Filipinos to fall behind to help save that bird,” Kennedy continues. “In fact, he ended up writing a check for 40,000 pesos out of his pocket, because he thought it was so important.

“It fueled a whole conservation movement,” Kennedy says, noting that today’s Philippine Eagle Foundation was created by the Philippine government as an offshoot of that first filming project. “There are a lot more people out there that are interested in trying to save it now than there ever were back in the ’60s and ’70s.”

A Philippine Eagle stands by its nest high in the forest canopy. Photo by Kike Arnal.

Rettig waited patiently from a treetop blind each day during the months-long nesting period. Photo by Kike Arnal.

A parent towers over its young, still-downy chick. Photo by Kike Arnal.

Both parents help to raise the chick. Philippine Eagles typically have one nesting attempt every other year, making them slow to recover from population losses. Photo by Kike Arnal.

A chick watches a parent return to the nest with food. Photo by Kike Arnal.

The Great Philippine Eagle was once known as the "Monkey-eating Eagle" for good reason. Photo by Kike Arnal.

A parent breaks off pieces of prey to feed its young chick. Photo by Kike Arnal.

Philippine Eagles hold large territories, making them particularly vulnerable as forests shrink due to logging and increased human settlement. Photo by Kike Arnal.

A parent flies over the large nest platform high in the canopy. Photo by Kike Arnal.

An eagle family at the nest. Photo by Kike Arnal.

The Pressures of a Growing Human Population

But the eagle isn’t saved. Population estimates of a secretive forest bird have always been a bit of a guessing game. A 2002 study, based on spacing between nests in suitable habitat, estimated that the maximum number of breeding pairs on Mindanao was between 82 and 233. Even the current total Philippine Eagle population estimate of 400 pairs is at best an educated guess.

But it’s clear the eagle’s forest habitat continues to shrink. Even though commercial logging was restricted in the 1980s and 1990s, illegal logging has continued as poverty-stricken villagers have followed logging roads deep into the forest and continued cutting trees for slash-and-burn farming. Estimates of remaining forest coverage range from about 20 percent to less than 10 percent, and much of what remains is fragmented and in poor condition.

At the same time, the population of the Philippines has nearly tripled since 1970 to more than 100 million.

“There’s a huge population of people that are just scraping a living off the land throughout the country,” says Kennedy, who with several coauthors wrote A Guide to the Birds of the Philippines. “And any available land, whether it’s forest or not, is pretty well taken up quickly by squatters in the mountains.

“That is the primary threat. The logging industry is certainly to blame to some degree, but they were regulated by the government to selectively log and then to allow for regeneration when they could log again. But the problem really was that the loggers would build roads to get that timber out, and that provided the avenue for people to migrate into the hinterlands. So it accelerated the total destruction of the rainforest in areas.”

Kennedy himself is pessimistic about the eagle’s future.

“I don’t give the wild population much hope unless the socioeconomics of the country change dramatically,” he says. “I don’t want to be a doomsday guy. I want to be as optimistic as possible, but I just don’t see how this eagle can hang on into the next century, unless they provide massive management, supplemental feeding to wild birds, maybe even artificial nesting structures.”

If there is a bright spot in the eagle’s future, it’s the Philippine Eagle Foundation, “probably the most successful conservation effort in Asia,” says Kennedy.

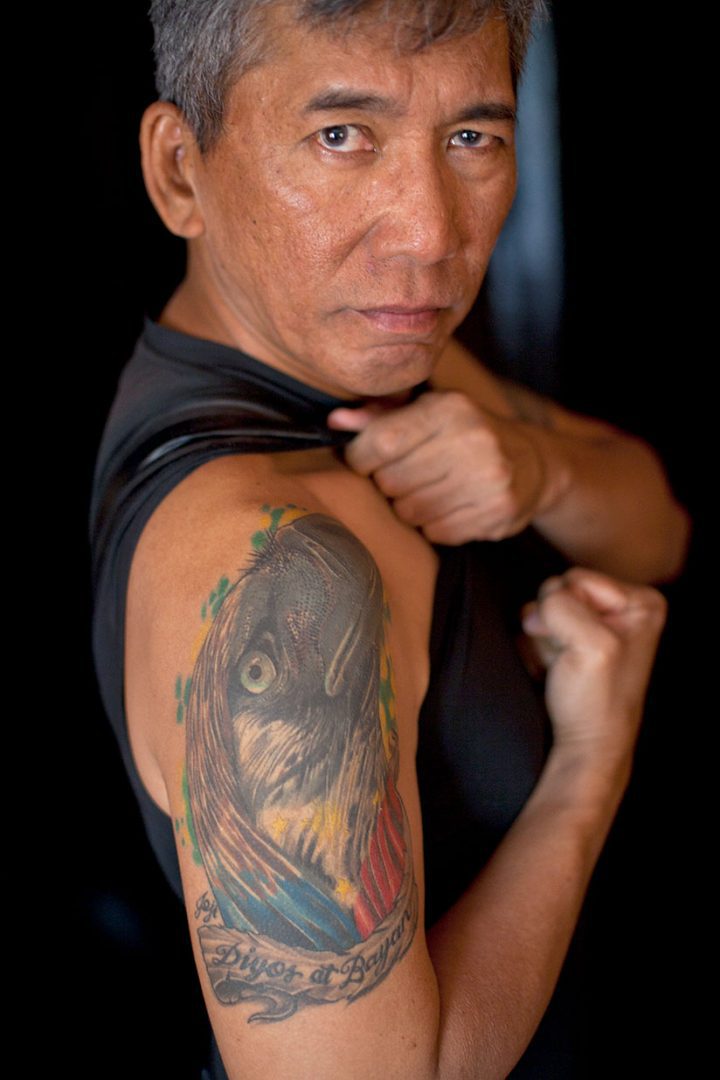

Cut loose from government support in 1987, the foundation has found private donors and grown to about 55 staffers, says director Dennis Salvador. The foundation has successfully bred and raised 27 Philippine Eagles in captivity since 1987, a strategy that may keep the species in existence if everything goes wrong in the wild. The foundation also rescues, rehabilitates, and releases injured eagles. Released birds are outfitted with GPS and radio transmitters so that biologists can track their recovery in the wild.

Last year an eagle that had been rehabilitated and released in 2010 made a nesting attempt, and even though the egg didn’t hatch, the attempt “underscores the potential of rescued birds,” says Ibanez, the foundation’s research and conservation director.

That eagle, released in one block of forest, followed a river corridor to another chunk of forest. Understanding how eagles move across the landscape allows the foundation to design management plans and forest corridors that help the birds make the most of their dwindling habitat.

“This gives us an idea of dispersal patterns, that they don’t fly outright from one big forest block to the other, but they use stepping stones or linear habitats,” says Ibanez. “This can guide restoration initiatives, to allow connectivity between forest fragments, and doing that through community-based reforestation, primarily of river systems.”

In another case, a young injured bird was nursed back to health in 20 days and released to its home.

“The parents took it in and resumed feeding of this young bird, which is also a big success in terms of rehabilitation protocols,” Ibanez says.

But tracking tagged birds has revealed a problem that has proved to be as vexing as habitat loss. People are shooting them at an alarming rate.

“We believe that many of these young birds do not survive into adulthood mainly because the forests are diminishing and when they cross open landscapes, they get shot or captured,” says Salvador.

On several occasions, foundation workers and volunteers have joyously and hopefully celebrated the release of a rehabilitated bird only to follow its transmitter months later to a pile of feathers and bones with the telltale marks of a bullet from a rifle or pellet gun. Ibanez reports that of 10 birds released since 2008, three were shot, one was illegally captured and died, and another disappeared and is believed to have been shot.

Since the birds breed every other year and produce only a single chick, the loss of every bird is devastating. “Just one crazy person can undo everything that we work for,” says Salvador.

The motivations for poaching range from food—one eagle was made into soup—to retaliation for pilfered chickens and piglets. Other shootings seem completely gratuitous. Ibanez blames a trophy culture: “The idea of shooting a really huge bird. It gives them this fulfillment.”

Though killing eagles is illegal, prosecution may be more effort than it’s worth. One prosecution took three years, says Salvador, “and the judge slapped him with a six-month sentence.”

Instead, the foundation is working with forest communities to reforest cleared areas and protect existing forest so the birds can travel and hunt in safety. It’s hiring local forest guards to deter crimes such as clearing trees and shooting eagles—and to provide jobs that give local residents a reason to value conservation. According to Ibanez, the foundation employs more than 700 local forest guards in 20 eagle territories.

Foundation workers and biologists have also found new areas of breeding eagles, on the island of Leyte, where the eagle was thought to have been extirpated, and in areas of the northern island of Luzon, where the species wasn’t known to occur.

The fieldwork can take workers into disputed territory—the more isolated for eagles, the more hazardous for humans.

“It is dangerous work, mainly because you don’t know when encounters between the rebels and the military will occur,” says Salvador. “So we find ourselves having to ask permission from the military to enter an area and make sure the other parties are aware that we’re operating in the area. Sometimes it’s difficult when you’re caught in the middle.”

Foundation staff have been caught in crossfire, with artillery shells exploding just 50 yards away. Salvador says that a colleague died in a crossfire exchange.

“Peace and order, especially in Mindanao, continues to be a big problem,” he says. “That’s really basically a fact of life in working in the forest. Not only in Mindanao, but in many areas throughout the country.”

At its Davao City headquarters, the foundation offers guided tours of the Philippine Eagle Center, along with educational presentations for school kids.

Rettig’s films from the 1970s have been a key part of the educational efforts, even if they are showing signs of wear and tear. The old, faded and grainy footage has still been the most important tool for spreading the story of the Philippine Eagle, says Salvador.

“It’s just so regal and big and nothing compares to [it],” he says. “You have to see to believe and begin to take pride in what we have, especially our countrymen.”

A Return Trip Brings Hope

In November 2013, Rettig returned to the Philippines. Arriving in Davao City, a city that had tripled its population to 1.6 million, he was stunned by the sheer humanity, noise, pollution, traffic, and congestion.

But compared to his first film project, when Rettig and crew were on their own in the search for eagles, this time they had plenty of help. The Philippine Eagle Foundation took them directly to nests.

“Without them, we couldn’t have done it,” says Rettig.

At dawn Rettig and his fellow cameramen again climbed high into the trees, remaining motionless, eyes glued to their viewfinders until sunset—the same swarms of gnats as before, the same long hours of tedium punctuated by glorious moments when adults flew into the nest, or the chick took its first clumsy wingbeats to a nearby branch.

All the time as Rettig watched a young eagle through his viewfinder, he wondered to himself, “Where will it go?”

“When I look at that, through that tunnel of vegetation, at that ancient scene, I think, what future does that little guy have? How’s he going to find his own territory, when all the surroundings here have been completely altered by human landscapes?”

One day an adult swooped into his viewfinder and knocked its mate off its perch. Rettig was filming a Philippine Eagle courtship behavior.

“They locked talons together, spiraled down, embracing each other, and then flared off at the last moment and soared in unison riding the winds up along this forested cliff face,” Rettig recalls. “They spent hours aerial like that all through that day. It was really almost like a celebration of life, a bonding event. It was beautiful to see. I’ve never seen anything like that.”

After six months Rettig had the images he needed—of adults swooping through the canopy, gently tending to the chick, even prowling the forest floor for prey. And this time, the Ultra-HD footage can be archived digitally and used forever.

In the three years since he completed filming, Rettig has worked with the Cornell Lab to produce several films for the Philippine Eagle Foundation to show in rural communities near eagle territories, and to school groups and families at the Eagle Center. A feature-length documentary—entitled Agila: Laban Ng Lahi (or Eagle: Fight of Our Race)—debuted on the largest TV network in the Philippines in June 2015.

“The images are really awesome,” says Salvador. “The high-definition cameras really do justice to the eagle, especially for people who have never been to a forest.”

Salvador says that if the Philippine Eagle is to be saved, it will require a mass movement among Filipinos everywhere for the country’s national symbol. And, he stresses, the eagle can still be saved.

“I don’t think it’s too late,” Salvador says. “I think we have a real chance of saving the eagles, even with the little we have left. It’s just a matter of political will and attitude of the Filipino people.”

The foundation’s Ibanez says the fight is not just for the future of the Philippine Eagle, but for Filipinos themselves.

“As Dr. Dioscoro Rabor said, ‘The Philippine Eagles are as Filipino as we are,”’ Ibanez says. “If we let deforestation destroy all our forests, if we let our fellow Filipinos shoot and hunt the Philippine Eagles, if the Philippine Eagles get extinct because of these wrong doings, it only means that we have lost our connection to the environment.

“And at the end of the day it would be the Filipinos who would suffer with the loss of our eagles and our forest.”

Freelance contributor Greg Breining has written about science and nature for the New York Times and Audubon. His story on Kirtland’s Warblers ran in Living Bird Summer 2017.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you