Laysan Albatrosses Survived the Feather Trade, Industrial Fishing, and Plastics. What’s Next?

By Hugh Powell

December 19, 2017

The following article has been excerpted from Facing Into the Wind: The Complicated Fate of the Laysan Albatross, which first appeared in the Summer 2014 issue of Living Bird, our member magazine.

Looking ahead at the 21st century, unfortunately it looks like sea-level rise is going to drown the Laysan Albatross’s current colonies, and land-use wrangles and predation are going to take down the colonies of the future. So where exactly is the hope for Laysan Albatrosses? Because there is reason for hope—and it resides in three unlikely sounding stories: feather hunting, fishing bycatch, and plastics.

The feather trade almost put an end to Laysan Albatrosses right at the start of the 20th century. In 1902, Japanese feather hunters began a wholesale destruction of Hawaiian seabird colonies to supply Western hat-makers. By the time feather hunting was banned in 1922, only an estimated 18,000 Laysan Albatross pairs were left in the world. (There had been an estimated half-million pairs on Laysan Island alone.) Their numbers began to improve—remarkably quickly for a bird saddled with a low reproductive rate. They reached 280,000 pairs in 1958 and have doubled again since then.

The next obstacle the 20th century had in store was industrial fishing—but it’s also a conservation success story in progress. Two kinds of fishing are particularly bad for albatrosses: drift nets that cover large expanses of surface water and longline rigs, which are used to catch many of our favorite seafoods: tuna, haddock, cod, swordfish, and Chilean sea bass, to name a few. The ships use lines up to 60 miles long.

As the global appetite for seafood increased, so did the scale of the problem. In 1991, an Australian biologist estimated that Japanese longline tuna fleets were setting 108 million hooks and killing a staggering 44,000 albatrosses per year. Drift nets placed in the high seas were killing as many as 27,500 albatrosses per year in the North Pacific alone.

The numbers were so unsettling that action was swift. Drift netting was banned in 1992 by international agreement (it still goes on in some national waters), and people started looking for ways to reduce longline bycatch.

To do this, biologists worked with fishermen. They needed methods that were straightforward, inexpensive, and didn’t reduce the fish catch. Fortunately, the industry was motivated.

“If you lose a lot of bait to birds, you don’t catch a lot of fish,” said Ed Melvin, who studies bycatch at the University of Washington. “So the motivation is there at two levels. Fishermen say albatrosses are the souls of fishermen. So I’m really optimistic that if we can come up with practical tools, they’re going to be used.”

In Alaska and Hawaii, fishing fleets were also motivated by the Endangered Species Act, which protected Short-tailed Albatrosses and green sea turtles. Ships that didn’t avoid bycatch could have their season shut down. Laysan Albatrosses benefited by extension.

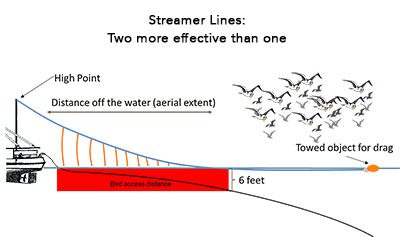

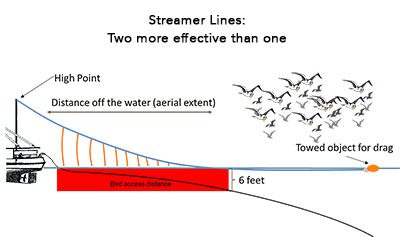

In the end, three fairly simple measures turned out to be about 90 percent effective when used together: First, hang gaudy streamer lines behind the ship to scare birds away from baited hooks until they sink out of view. Second, weight the baited lines so they sink faster. Third, bait the hooks at night, when most seabirds are less active.

What You Can Do

Of course, finding the answer is not quite the same thing as solving the problem. Fisheries use many different kinds of gear; fishermen speak many different languages; regulations and oversight are slow to be enacted.

But when drift nets were banned, bycatch of Laysan Albatrosses dropped from a high of around 30,000 per year to about 3,000 per year. When the Hawaiian tuna fleet adopted longline measures, it dropped again, from 1,500 per year to 100 per year. Bycatch is still regarded as one of the primary threats to albatrosses and petrels, but at least we’re not still searching for the way to fix it.

In the late 20th century emerged the problem of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch—the detritus of modern life that accumulates in the centers of ocean gyres. By one estimate, Laysan Albatrosses cumulatively feed five tons of plastic each year to their chicks. Kaloakulua, the chick on the Cornell Lab’s 2014 albatross cam, had plastic in her stomach by the time she was 4 months old.

Sometimes the animal you’re trying to save can surprise you, though. Plastics are less dangerous to albatrosses than has been suggested, Flint told me.

“They don’t eat plastics by mistake,” Flint said, “They seek them out and swallow them on purpose because they’re a substrate for flying fish eggs. If you walked around an albatross colony in the 1950s, you would find albatross carcasses full of pumice and sticks and wood.

“They’ve been eating natural plastics all their life,” she said, referring to the hard, sharp beaks of squid that are the albatrosses’ main food. Flint stressed that plastics do pose problems: they harm species lower on the food chain. They also accumulate toxins from the water and can pose a chemical threat when swallowed. But they do not necessarily cause albatross chicks to starve. Before fledging, most albatross chicks cough up plastic and squid beaks alike to clear their stomach before taking their first flight. Kaloakulua successfully regurgitated her “bolus” of stomach contents on June 1, 2014. This video shows a Kauai Albatross Network volunteer examining the plastic that it contained.

To read the rest of the article, click through to Facing Into the Wind: The Complicated Fate of the Laysan Albatross.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you