Who Lives, and Who Dies: Is Conservation “Triage” a Good Idea, or a Dangerous One?

By Sarah Gilman

Northern Spotted Owl by Alexander Clark. June 6, 2018From the Summer 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

When Mike Scott started working a job as a U.S. Fish and Wildlife service biologist in Hawaii in 1974, very little was known about the island chain’s forest birds. But the U.S. had just passed its landmark Endangered Species Act in 1973, and the islands were home to 20 of the birds included on the first endangered species list.

So over the next decade, Scott and three other researchers thrashed through sodden jungles to learn what birds still lived there, where, and in what numbers.

“It was 19th-century biology,” Scott recalls.

The survey results were disheartening. Several native forest birds, such as the Maui Akepa and the Poouli, had populations in the low hundreds; others like the Molokai Olomao were down to 20 individuals or fewer.

“We said … we should start the conversation about captive propagation,” recalls Scott, now an emeritus professor at the University of Idaho and an authority on U.S. endangered species policy. “The universal reaction was, we don’t know enough to be able to save them,” Scott says. So the agency didn’t follow through on captive-breeding programs.

In 1984, Scott transferred to the mainland to head USFWS efforts to recover the California Condor. It was immediately apparent to him that a choice had been made. The condor was also on the verge of extinction, and no one knew how to save it, either. Yet the federal government and partner organizations mounted a massive effort to pull condors from the wild for captive breeding. By 1987, when all the condors had been caught, there were just 27 in the world.

In 1987, the remaining 27 California Condors were caught and a captive breeding program started. Photo by Claudio Contreras/Minden Pictures.

That same year, the Kauai Oo sang its last song. illustration by Walter Rothschild PD-US.

During that same year—1987—biologists in Hawaii’s Alakai forest heard the eerie, descending notes of a dark, jumpy little bird with a gracefully curved bill: the Kauai Oo. It was a breeding song for a mate that would never answer, because that male Oo was the last of his kind. He was never heard again.

Today, after attention from biologists and millions of dollars in investment, the condor population has climbed above 450 birds, half of them flying free again in the wild. Meanwhile on Hawaii, several of the dwindling bird species pinpointed in the forest surveys are extinct, or likely so. “And nobody did anything,” Scott says. “There wasn’t much ruckus about it.”

As far as Scott knew, no one was presiding over a boardroom table pointing out who would live and who would die. But the USFWS, which stewards most species listed under the ESA, was neglecting some by default. In theory, that’s not supposed to happen. The law tasks the USFWS and the National Marine Fisheries Service with leading federal efforts to safeguard and recover all those species under their care. But legal experts say that courts allow the agencies a lot of leeway in deciding what proactive projects to undertake to benefit the more than 1,600 animals and plants listed for Endangered Species Act protection today.

Limited Funding Brings Tough Questions: Who Lives and Who Dies?

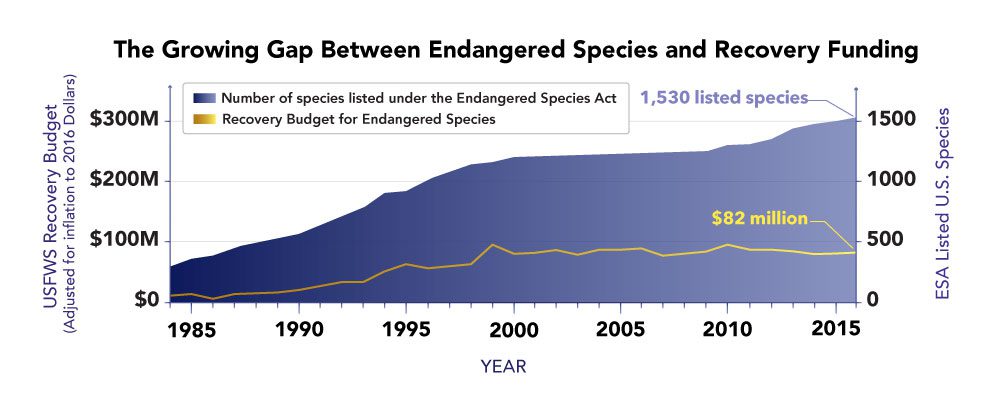

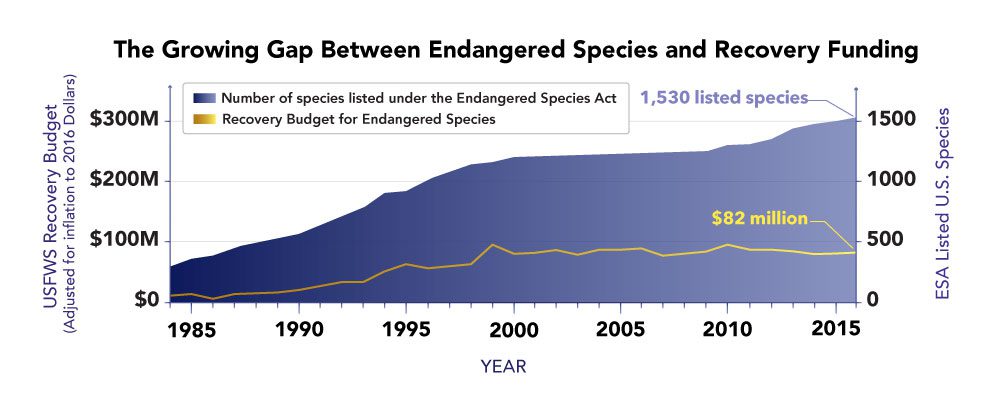

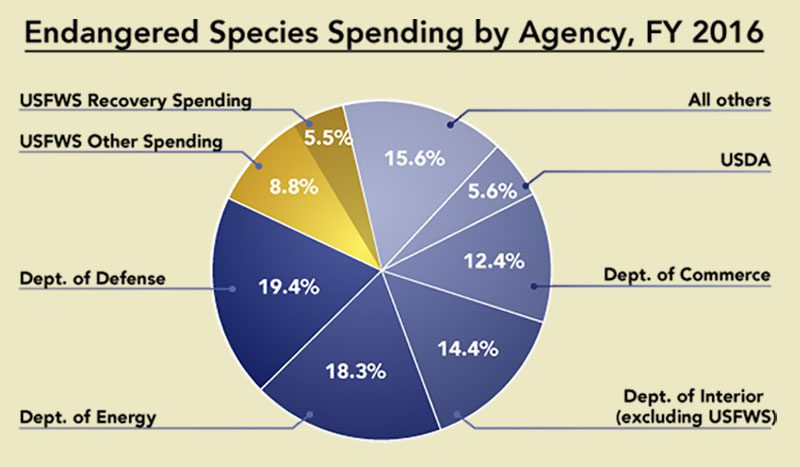

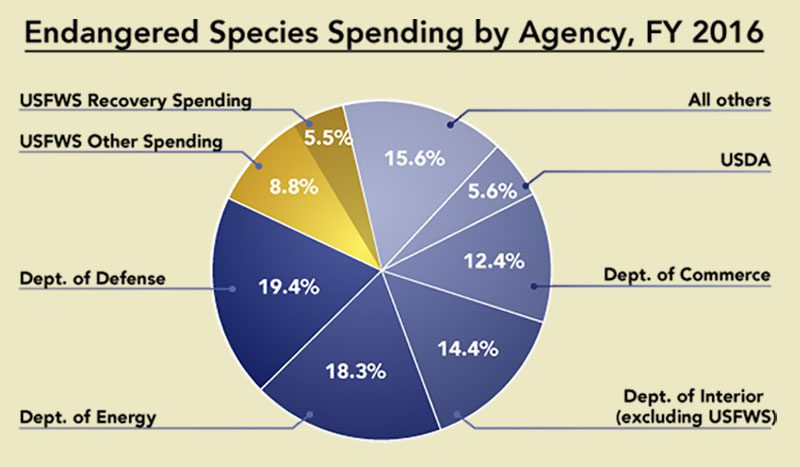

Meanwhile, ESA funding is scant and wildly disproportionate. According to a recent paper published in the journal Issues in Ecology, total ESA spending over the past 15 years would cover only about one-third of listed species’ recovery needs. In 2016 (the most current set of available numbers) nearly half the $1.4 billion federal investment into endangered species went to just 10 species, seven of them fish. Between 1998 and 2012, about 5 percent of ESA-listed species received more than 80 percent of ESA spending, while 80 percent of listed species received just 5 percent.

Every choice we make, there’s a consequence.

~Arizona State University biology professor Leah Gerber

What’s more, there are likely many more species in existential crises than now receive protection under the law. The Issues in Ecology paper says that the actual number of species at risk of extinction may be five to 10 times greater than the number of listed species. Yet the USFWS endangered species recovery budget has been stagnant for the past decade.

“The service is constantly juggling the demands of increasing conservation workload with limited resources,” says Jeff Newman, USFWS chief of restoration and recovery. “Most decisions we make prioritize certain work activities and species’ needs over others.” To help with that decision making, a team of scientists reached out to the agency with an offer to create a mathematical tool (see sidebar) that they hope will help it prioritize creatures and projects in a more systematic, transparent way, within its budget—the sort of information that could explain, for example, why condors got help, but not those struggling Hawaiian forest birds.

“Every choice we make, there’s a consequence,” says Arizona State University biology professor Leah Gerber, a primary investigator on the team developing the ESA prioritization tool. “Right now we’re sort of burying that.”

Adds Michael Runge of the U.S. Geological Survey, another primary investigator: “The point is how to most cost-effectively recover listed species.”

But for critics, such efforts can look like tacit acceptance of the problem’s root cause: a severe funding shortage. The question, they argue, shouldn’t just be how to stretch scarce dollars to cover more species, but how to get more money for endangered species conservation in a nation where Americans spend $80 billion a year just on soda.

“Prioritization should not have an artificial funding cap,” says Loyal Mehrhoff, who managed endangered species programs in Hawaii for five years as the field supervisor at the USFWS Pacific Islands office before retiring and accepting a position at the Center for Biological Diversity. “I find it almost impossible to believe that we don’t have enough money.”

Species Triage: The Knapsack Problem

In early media reports, the tool that Gerber and Runge are spearheading quickly attracted the label of triage—a term that’s sometimes considered a fighting word in conservation circles.

Everything that they put in means something else comes out.

~Hugh Possingham

In the triage metaphor, conservation is likened to battlefield emergency medical care, where biologists and officials must apply scarce resources to too many patients, ordering care to address the most pressing needs first. In some cases, that ordering may mean letting go of those that are unlikely to recover, too expensive, or less important.

The Nature Conservancy’s chief scientist, Hugh Possingham of Australia, helped pioneer mathematical approaches designed to tackle the issue of how to make such decisions. He describes the dilemma of working with a finite sum of money as a “knapsack problem”: If someone is camping and their pack can only support 20 kilograms, how should they decide what to put in it?

“Everything that they put in means something else comes out,” Possingham says. “I’m sure they’d like to have five kilograms of chocolate. But they might prefer to have a tent.”

In the United States, discussions to this effect are almost as old as the ESA itself. In the late 1970s, when the program had a budget of $10 million and 15 staffers, then-director Keith Schreiner told The New York Times that it would take 6,000 years just to list all the endangered species, let alone develop recovery programs for them.

In 1983, the USFWS began assigning ranks to ESA-listed species based on factors like degree of threat, taxonomic uniqueness, and feasibility of recovery. But according to a 2005 analysis by the Government Accountability Office and more recent reports and interviews, factors like office workload, Congressional earmarks, and the potential for attracting extra money through partnerships have mattered more than the rankings when it comes to which species got recovery money first.

In an effort to help the U.S. government use limited funds more strategically, Gerber began her project in 2015 with the support of the University of Maryland’s National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center. Over the next three years, through the beginning of the Trump administration, Gerber and a team of more than a dozen experts and USFWS staff met to refine an assessment tool for ESA resource allocation, provide feedback, and nail down details.

The stakes were clear. The ESA has led to some unequivocal successes, directly preventing the extinction of more than 200 species. Eighty-five percent of listed continental birds have either stabilized or increased under its protection, according to a Center for Biological Diversity review. But in other ways, implementation has been lacking. Fewer than 2 percent of all ESA-listed species have successfully recovered to the point of delisting. And around half of all listed species are either declining or still critically endangered. Of 1,125 ESA recovery plans Gerber reviewed in her own research, around 1,000 were inadequately funded, often devastatingly so.

“If people try to frame [the ESA] as trying to address a biodiversity crisis, then spending money the way we do now does not make sense,” says Timothy Male, executive director of the Environmental Policy Innovation Center, who also worked on Gerber’s project. The resulting tool would allow the agency to take another look at the numbers, comparing what it’s currently doing with what the tool suggests it could do. Its terms are not yet public. The scientists expect to release it later this year, after it has gone through peer review, at which point the USFWS must decide whether and how to use it.

In essence, the approach gives decision-makers a framework for weighting each species based on categories like taxonomic uniqueness, while also considering cost, benefit, and probability of recovery. The end result will be a ranked list of projects or species that best meet the government’s goals given a specified budget. The list, for example, could help the agency figure out which species need the most attention, or whether some hard-luck cases are sucking up resources while other species that the tool identifies as having a clearer chance of success are being neglected.

The outcome depends on what goals the agency sets. As Gerber explains it, if USFWS chose to maximize extinction prevention, the tool might tell the agency to tackle expensive, critically endangered species first. But if the agency chose to maximize the number of species recovered over a long time frame, the tool might tell the agency to favor those species with the best chances—those that are more abundant, or need less costly interventions.

Regardless of the approach’s outcome, though, any actions the agency takes would still come down to judgment: An ordered list would be only one of the many things the USFWS would consider as it aims to meet the legal obligations of the Endangered Species Act. The Nature Conservancy’s Possingham, who has also advised on Gerber’s project, puts it this way: “We’re giving [the USFWS] a tool, not an answer.”

Prioritizing Species Down Under

Trained in mathematics and decision theory, Hugh Possingham began developing some of the ideas behind the conservation triage approach while teaching at universities in Adelaide and Queensland, and serving as chair of a biological diversity advisory council to Australia’s federal government in the late 1990s and early 2000s. At the time, Australia based its funding decisions on which species made its critically endangered list. Because the approach didn’t take into account the limited amount of money available for endangered species, Possingham worried, it could lead to a larger number of struggling species going extinct over time.

“I find it alarming that in conservation, they don’t formulate problems properly,” he says. “What happens if there are 10 vulnerable species and they could be saved for $10,000 each, and one critically endangered species that could be saved for $1 million? If you pick the critically endangered species, then you’re letting 10 other species go.”

He and others produced a series of papers exploring mathematical approaches to investing wisely and actually maximizing species conservation.

Richard Maloney of the New Zealand Department of Conservation’s Biodiversity Group reached out to Possingham’s group with a problem. In New Zealand, more than 3,000 species are classified as imperiled in some way, with 800 at risk of extinction.

The ecological cost of losing any is especially high because it’s an island nation with high biodiversity; more than 70 percent of its 218 native bird species are endemic, found nowhere else in the world.

Yet in 2006, New Zealand’s Department of Conservation was struggling to keep up, managing just 22 percent of its threatened species, often inadequately.

“It was clear to us that the amount of planning … and work around threatened species didn’t match the scale of the problem,” Maloney says.

One of Possingham’s graduate students, Liana Joseph, began working closely with Maloney and the three produced a formula called the Project Prioritization Protocol, or “PPP.” The New Zealand government used the PPP to produce a draft list of 100 species prioritized for population enhancement, based on the urgency of their situation, whether helping them would ensure a broad representation of New Zealand taxa survive, and the cost effectiveness of working on them. In order to create the priority list, the department had to develop hundreds of species conservation plans with cost estimates.

The process has helped the Department of Conservation increase the number of species it’s actively managing. More than 500 threatened species are now benefiting from some kind of management, including 93 species that are receiving all the management they need to persist for the next 50 years. The department hopes to be fully managing 500 species for persistence by 2025, and keep ramping up from there.

Regardless of what values a PPP-generated list relies on, though, not all important imperiled species will make the cut. So the New Zealand Department of Conservation devised other programs, such as an iconic species management list for 50 charismatic creatures, including the kiwi—the country’s national bird. Advocates of the PPP process say developing a clearly articulated strategy not only gets more bang for conservation bucks, but it can also show specifically what managers could do if given more resources. In other words, the process of conservation planning with cost estimates can provide lawmakers with a compelling reason to boost funding.

That’s what happened in the Australian state of New South Wales, where the PPP process was also used in threatened-species planning, and conservation managers were able to use the strategy to secure an additional $100 million commitment from the state government over five years.

“That’s an unprecedented amount of money, in our agency, and nationwide,” says James Brazill-Boast, senior project officer with the New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage. Brazill-Boast says the new funding allowed his agency to triple the number of threatened species receiving attention, with more than 300 receiving comprehensive investment.

It will be decades before it’s clear in New Zealand or New South Wales whether managing more imperiled species translates to more species actually recovering in population numbers and range. But Maloney of the New Zealand Department of Conservation is firm on one point: “It’s not about giving up on stuff. It’s about saving the most things.”

The Moral Hazard Of Triage

Stuart Pimm thinks that, in the United States, there’s a good chance it actually would be about giving up on stuff.

The USFWS endangered species decision-making tool that Gerber, Runge, and others are developing is partially based on the PPP, and Pimm, a conservation biologist at Duke University, worries that the U.S. government might apply it very differently. Australia and New Zealand are “not everywhere,” he says.

New Zealand has a slew of bold governmental and cultural commitments to conservation—including a measure backed by the indigenous Māori people that puts the rights of a river on par with human rights, and a massive campaign to rid its islands of nonnative, invasive predators by 2050.

Meanwhile in the U.S., a perennial, fierce movement to gut the ESA is ramping up under a sympathetic presidential administration. Several bills introduced in the current Congress would significantly limit or alter the law’s implementation. In its first 18 months, the Trump administration twice unsuccessfully proposed to slash USFWS funding, including the ESA recovery budget and key grant programs that support listed species. And in April, the administration installed a noted proponent of rolling back ESA protections—former Texas comptroller Susan Combs—as acting assistant secretary for fish, wildlife, and parks. (The Austin American-Statesman newspaper reported that Combs has been involved in petitions to delist the endangered Golden-cheeked Warbler in Texas, despite that species’ critically low population earning a rating of “high conservation concern” on the State of the Birds Watch List.)

“The moral hazard of triage” is that it can give a patina of scientific justification to politically motivated decisions, argues Pimm. (Cornell Lab director John Fitzpatrick, in a 2018 Living Bird column, has a similar viewpoint.)

Daniel Rohlf, an ESA expert at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon, agrees that there is some danger there: “I think any time there’s an initiative that provides federal agencies with substantial discretion to make choices, you do run a risk that they will say something like, ‘Well, yeah, Mexican wolf recovery is controversial, expensive, and logistically challenging, so we’re just going to direct our funds to species that are less controversial and less challenging.’”

Still, he adds, given that conservation need is likely to continue to outstrip resources, if the agencies end up with “a rational policy for making these difficult decisions, I think that’s a good thing.”

Even those working on the ESA decision tool, such as consultant Timothy Male, acknowledge that the agency may have to consider updating its evaluation data for the tool to work well. The estimates of cost and feasibility of recovery that the tool would use come from documents that are largely out of date. Many recovery plans are 20 to 30 years old, and five-year status reviews meant to check progress are also critically behind.

For example, the Florida Scrub-Jay—an ESA-listed corvid with striking blue feathers that appears to sport the gray sweater vest and brows of a distinguished older gentleman—is decades overdue for a planning update. Its recovery plan is 28 years old, and its most recent status review was 11 years ago. Efforts to update conservation plans have bogged down with the USFWS, says John Fitzpatrick, director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, who has studied the bird in the field for more than four decades, and is cooperating with the agency.

“We know more about the biology of this species and what it needs than we know about any other endangered species on the list. And we could save it with a relatively small investment, frankly,” Fitzpatrick says. Instead, the Florida Scrub-Jay’s 90 percent population decline continues apace, and small populations are winking out due to development and fire suppression.

The application of Gerber’s tool may itself be limited by the sparse discretionary funds available to the USFWS for endangered species recovery. Certain actions, like mitigating impacts from federal projects, are compulsory under the ESA. That’s why so much of the ESA spending total goes toward fish, which are affected by projects such as hydropower dams. For example, the Bonneville Power Administration (part of the Department of Energy) operates dams in the Pacific Northwest, and it must shell out cash for mitigations like habitat restoration to help ensure that populations of ESA-listed salmon and steelhead trout persist despite development. Those sorts of expenditures account for a great deal of the $1 billion-plus total invested in endangered species each year, across nearly 30 federal agencies. The amount of money in the USFWS recovery budget, on the other hand, is much lower—just $84 million in 2017. And even much of that is tied up in things like staff salaries.

“There’s not enough discretionary money to make the difference no matter how you allocate it,” says Noah Greenwald, endangered species director at the Center for Biological Diversity. “The vast majority of species are not getting the money they need. Triage is not going to help that problem, and it might make it worse.”

Conservation scientists John A. Vucetich, Michael Paul Nelson, and Jeremy T. Bruskotter echoed that concern in a 2017 critique of the conservation-triage concept published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. While acknowledging that a government conservation agency has a responsibility to seek to spend its money wisely, they wrote: “a second responsibility is to advocate to its constituents the need to allocate enough resources for conservation. Given the severity of the shortfall, this second responsibility is arguably more critical…. To think otherwise may be analogous to arranging deck chairs on a sinking ship in the most efficient manner.”

Facing Extinction: “We need help.”

Even Possingham is reluctant to accept the low funding levels for the ESA in a nation as rich as the United States. “The U.S.,” he says bluntly, “has no excuse for not being able to recover all of those threatened species.”

Back in 1987—when every California Condor had been rounded up from the wild, and every Oo was gone—the last known Dusky Seaside Sparrow died in captivity in Florida. No bird has gone extinct on the U.S. mainland since, but a related species called the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow is perilously close to being next.

There are just 61 birds left in the wild. And the more than $1 million in federal grants and other funds that have helped support a Florida Grasshopper Sparrow recovery and captive breeding program have been spent down to $250,000, with little sign of more coming from the national office, despite the concerted efforts of local staff.

USFWS biologist Ashleigh Blackford, who works on the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow project, tries to sound upbeat: “We’re really familiar with working with small pots of money to make things happen.”

But the agency’s Florida State Supervisor of Ecological Services Larry Williams says the project is running into some hard financial realities: “I began to tell the team here, ‘We need to continue to invest in Grasshopper Sparrows’ most critical things, but we can’t let all of our budget go into Grasshopper Sparrows.’

“We have 120 other [ESA-listed] species we need to be helping to recover,” he says.

But, Williams adds, he also doesn’t want to abandon hope: “Just to be kind of direct, the main message we’re trying to get out to people is that we need help. This one is in critical condition.

“We need help.”

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you