A Galaxy of Falcons: Witnessing the Amur Falcon’s Massive Migration Flocks

By Scott Weidensaul

Background photo by Ramki Sreenivasan, Amur Falcon by Kevin Loughlin. June 13, 2018From the Summer 2018 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

For hours, we fishtailed and jolted along a rutted, muddy, single-track road through the low mountains, nervously watching the sun slide lower and lower. The forested, gently crumpled Naga Hills looked lovely in the late, buttery light, but we’d been repeatedly warned to be off the road before dark given the risk of bandits and armed insurgents in this remote and troubled corner of northeast India, not far from the northern border of Myanmar (Burma).

We had no idea how much farther ahead lay our destination, a village known as Pangti, or whether we’d actually reach it before nightfall. Worse, the skies around us were largely empty of birds—which was more than a typical birding-trip disappointment. My colleagues and I had come here, to the state of Nagaland, in search of what’s reputed to be the single greatest gathering of birds of prey on the planet. And I wanted to learn more about how a shocking conservation tragedy had, in a very short time, become a stunning conservation success.

By all accounts, the skies should have been alive with lithe, sickle-winged Amur Falcons, pausing here on their epic migration from eastern Asia to southern Africa. Instead, hour after hour we’d seen little in the air except a few swallows.

“I don’t know. This should be just a highway of falcons,” said Abidur Rahman, a young ornithologist from the neighboring state of Assam and our guide for this trip. We were by now skirting the Doyang Reservoir, a hydroelectric impoundment along which the birds normally roost by the tens of thousands. We saw four.

We pulled into Pangti just as the sun dropped below the horizon. The village sat at the peak of a broad, defensible ridge—typical of the Naga, a Tibeto-Burmese culture whose tribes were traditionally headhunters, each village warring constantly with its neighbors. Today, they are overwhelmingly Baptists, inhabiting a defiantly un-Indian part of India and trying for decades to break away on their own. Nzam Tsopoe, our host and the village’s assistant schoolteacher, greeted each of us in turn with a slight bow as he clasped our hands; he and his wife would be sharing their small, three-room house with us for the next week. Mrs. Tsopoe brought the evening meal from their dirt-floored kitchen—delicious pork that had seasoned for weeks in the smoke above the open cooking hearth, pots of sticky rice and dhal, long beans, and steaming boiled squash. As we ate, we tried to ease the kinks from our long-suffering bones.

There was a more immediate issue, though. Mr. Tsopoe introduced us to two young men, whom he said would be our guides in the morning. We asked them, are the falcons here? How many? “Um, one, two thousand,” one of the young men replied. Surely we’d misunderstood him, but no. Far from the sky-darkening multitudes we’d expected, he said, there were hardly any birds on the roosts at all. The monsoons, which usually end in September, had continued for week after rainy, flooding week through October, their southwesterly winds holding back the migrant falcons coming from the northeast. After two years of planning, and days of wearying travel, it seemed our journey had all been in vain.

A Conservation Sensation: Killing Grounds Become a Sanctuary

I slept poorly—partly because the Naga don’t use mattresses, and my wooden-plank bed had just a thin cotton blanket for a cushion, but mostly because the whole effort to come to Pangti now seemed to have been an enormous waste.

I had been lured here by news stories over the previous couple of years about Amur Falcons in Nagaland that seemed almost too good to be true anyway: Conservationists stumble upon a previously unknown concentration of raptors that is arguably the largest in the world, only to find that local hunters are slaughtering the birds at a wildly unsustainable rate. The news, and gruesome videos of the killing, catch fire online and ricochet around the globe. Yet within a year or so, the community decides to embrace protection and preservation; the killing grounds become a sanctuary, the trappers become guards and wardens, and residents of the village prepare to welcome birders.

As we would learn in the days to come, the bare bones of that story are basically correct. In 2012, a Naga conservationist named Bano Haralu, along with several colleagues from Conservation India, confirmed rumors that Amur Falcons had begun to gather each night by the hundreds of thousands in densely packed roosts along the Doyang Reservoir, with many more in neighboring areas—very likely the bulk of the entire global population. They also found that local fishermen, stringing their nets among the roost trees, were killing an estimated 140,000 falcons in just one 10-day period during the peak of the migration—-plucking the carcasses, smoking them over open fires to preserve them, then selling the birds in larger towns for badly needed cash.

The disturbing videos Haralu and her colleagues took, showing trappers ripping tangled falcons from the nets, and small boys bent beneath the weight of hundreds of dead and dying birds, went viral among outraged conservationists worldwide. Quickly, leading bird-protection groups within India and abroad, such as the Bombay Natural History Society and BirdLife International, decried the killing, as online petitions battered the government for action, and viewers around the world reacted with horror to the images.

“I witnessed a massive swarm of these little falcons flying into the South African town of Cradock to roost for the night,” one commenter wrote on YouTube. “There were tens of thousands and I stood in awe. I cannot believe that they are slaughtered like this in India. There must be a special hell reserved for these bastards.”

Of course, the reality was a bit more complicated—and less morally simplistic. In fact, Pangti and its neighboring villages agreed to abandon the hunt in surprisingly short order. In barely more than a year, the villages made a hard transition with serious economic consequences, giving up the income that falcon meat represented—partly because it was the right thing to do, and also because they’d been told by conservationists that tourism could make up the loss.

But as we’d found out, just getting to Pangti was not for the faint of heart, and not surprisingly, tourists have been thin on the land. Lying on my wooden bed, I wondered in the dark what happens when poor people make a wrenching decision, expecting an outcome that may take years to materialize, if ever.

“Oh, my God. Look. Look!”

Hot water, instant coffee, and tea were waiting for us at 3:00 a.m. when we climbed stiffly from bed. Along with Abidur and our drivers, with me for the trek was my friend Kevin Loughlin, owner of Wildside Nature Tours, who was exploring the feasibility of bringing American tourists to Pangti to see the falcons. For that, Kevin needed willing guinea pigs—me; Catherine Hamilton, a California bird artist whose participation was underwritten by Zeiss Sports Optics; and birders Peter Trueblood of California and his cousin-in-law Bruce Evans of Maryland, who thanks to a visa snafu would be joining us the following day.

The ride to the main roost site down by the reservoir took 45 minutes, and given the hour and the mood, no one had much energy or inclination to talk. Once or twice we were startled by the explosive warning “bark” of the small forest deer known as muntjacs off in the blackness. We covered the last half-kilometer on foot, still walking in silence, passing beneath tall elephant grass and arching bamboo. It was cool, with a light breeze and no stars, but soon I could see the silhouette of a 40-feet-tall wooden watchtower, newly built for visiting birders, which rose against the slightly lighter sky as we emerged along the edge of the lake. We climbed to a roofed platform just barely large enough for us, and waited.

Except for the chirping of frogs and the hushed voices of our guides below, there was no sound save for a dry rustle that I took to be the breeze in bamboo. But when Catherine raised her binoculars to peer through the murky twilight, she gasped.

“Oh, my God. Look. Look!”

Binoculars revealed what our eyes alone could not yet see—that the dimly lit air was filled with tens of thousands of falcons, rising in the gloom like a dense insect swarm from their roost a few hundred meters away and spreading out overhead. As the light grew, so did the number of birds, the whisper of their wings rising now to an omnipresent swish, like fast-flowing water. No one spoke; this time not from disappointment, but from awe.

“So…way more than a thousand,” I said at last. “Maybe…what? Fifty thousand? And that’s only what’s in the air.”

“Maybe twice that,” Catherine said in a hoarse whisper. Kevin was glued to the viewfinder of his camera, making the most of the growing light; Peter just stared, wide-eyed. For the next hour, the falcons would rise from the roost in a great tide, enveloping us in a chaos of wings and movement, then settle back down again until the air was empty. Then something—on one occasion, a jungle crow dive-bombing the trees—would set them off once more, and they would erupt in fresh waves tens of thousands strong, layer upon layer of slender birds on long, narrow wings, swirling in counterclockwise gyres.

Across the landscape, like smoke pushed by a light breeze, gauzy columns of thousands of falcons rose from other roosts and bent with the wind as they caught the morning’s first thermals. This went on for hours, each new, departing rush of birds seeming as though they must be the last in the roost—yet when we’d peer through our scope, the trees would appear as heavily laden with perching falcons as before.

A female and male Amur Falcon share a perch. Photo by Kevin Loughlin.

A male (top) and female Amur Falcon. These slim little raptors feeds largely on insects and are slightly bigger than an American Kestrel. Photos of male and female by Abhilash Arjunan/Macaulay Library.

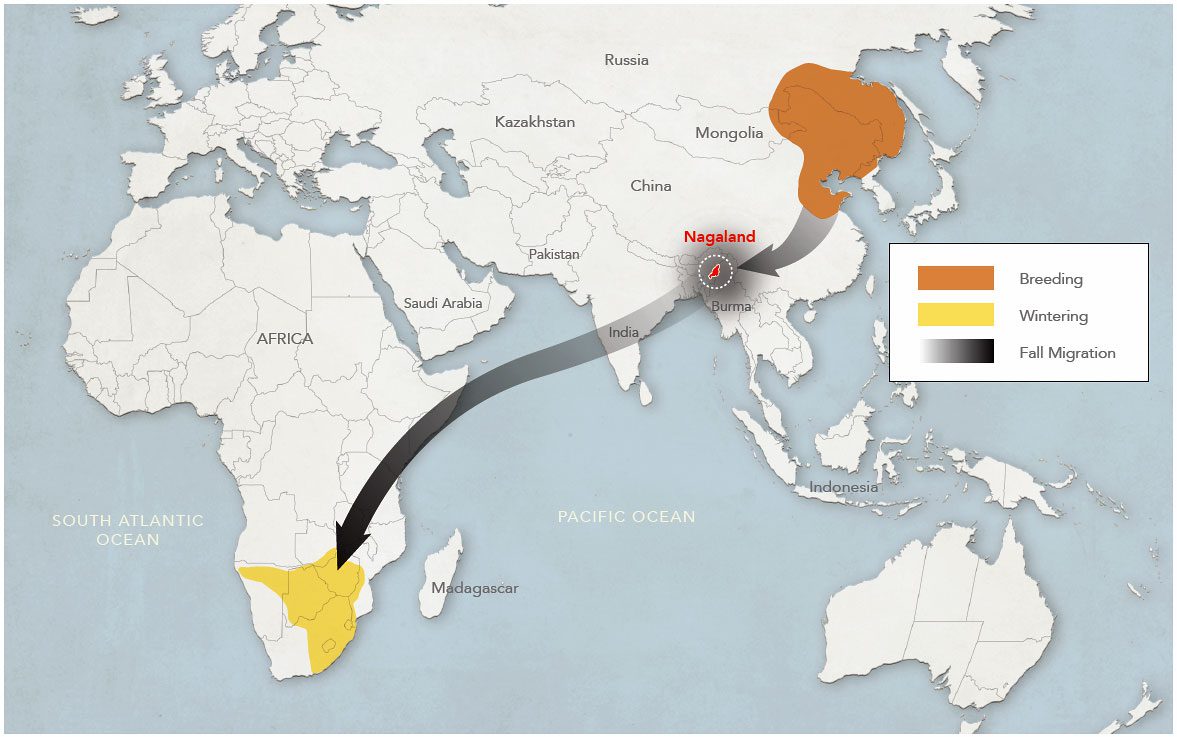

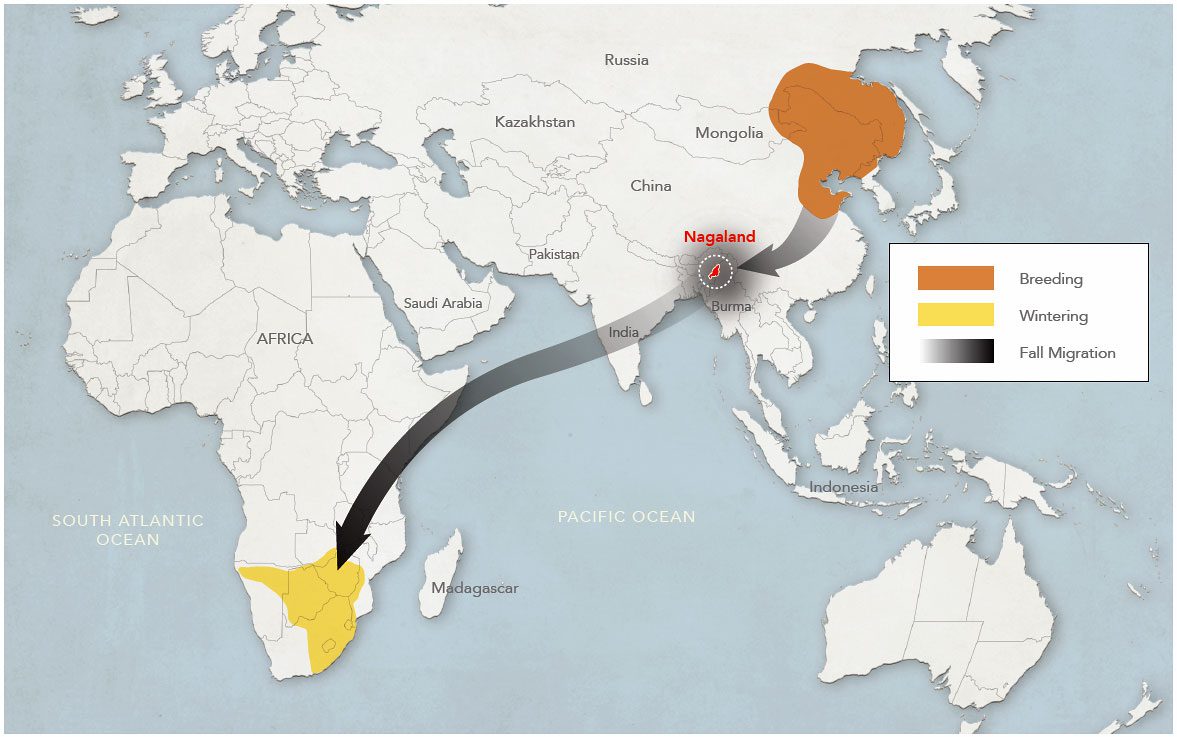

The Amur Falcon, a slim little raptor that feeds largely on insects, is slightly bigger than an American Kestrel. The males are dark gray above, paler below, with elegantly contrasting white wing linings and a splash of bright rufous on the thighs and undertail coverts. The females and juveniles are very different, their white undersides barred with black and lightly washed with buff on the chest, the face distinctly “mustached” after the fashion of most falcons. All ages and sexes have bright carmine legs and feet. The Amur was long lumped with the very similar Red-footed Falcon of western and central Eurasia. Amurs, however, breed in wooded margins and the edges of savannas from eastern China and North Korea to parts of Siberia and Mongolia (an area roughly a third the size of the Lower 48 in the U.S.), from which they make one of the longest migrations of any raptor in the world, some 8,000 miles one way to southern Africa.

In the process, they also undertake the greatest over-water crossing of any bird of prey, traversing as much as 2,400 miles of the Indian Ocean. Over water, the hot-air thermals and deflection currents that assist raptors migrating over land, allowing them to soar for hours and save energy, are largely absent. This means the falcons must beat their wings continuously on their transoceanic trip, which may take them four or five days. If they’re to survive, they must top off their tanks before they leave land.

And so in late October and early November, the migrant falcons pause for some weeks in Nagaland. At this same time of year, just after the monsoon, there is a great stirring underground as countless subterranean termite colonies prepare for the mating season. Worker termites chew tunnels to the surface, out of which emerge trillions of winged, inch-long fertile adults known as alates—fat-rich and the perfect food for an insectivorous falcon about to risk an ocean crossing.

A Bounty of Falcons Brings Manna From Heaven

It seems Amur Falcons have always stopped off in northeastern India during migration to feed on termites, but the completion of the Doyang Reservoir in 2000 dramatically altered the situation, for both the falcons and the local villagers. Although the Naga live in hilltop communities, their terraced fields, orchards, and rice paddies lie primarily in the valleys—in the case of Pangti, along the narrow flood plain of the Doyang River. While the 6,500-acre impoundment brought welcome electricity to the village, it also flooded many of those farms, including more than 2,000 acres of land cultivated by Pangti.

New fields on the mountain slopes were less productive, and wild elephants often trampled the crops. Some of the men shifted to fishing in the new reservoir, despite forests of sunken trees that tore up their nets. But the fishermen also noticed something they’d never seen before—that the falcons were now gathering in incredible numbers each autumn night in small groves of trees along the lake, then fanning out to hunt termites and other insects during the day.

Unlike most raptors, Amur Falcons are highly social most of the year. They travel in tremendous flocks, often with large numbers of Lesser Kestrels, and on their wintering grounds in southern Africa they gather by the hundreds or thousands each night in traditional, communal roosts. For reasons that remain unknown, the birds began to do the same on the Doyang, forming what may be the single greatest gathering of raptors in the world—pegged at about a million near Pangti alone, though no one has made a systematic count. Although some migration count sites such as Veracruz in Mexico tally up to 4.5 million passing raptors each season, only in Nagaland do raptors remain for long periods in such extraordinary numbers. Researchers are only now exploring how long the falcons stay and how much weight they gain while there.

The Naga, with their torn nets and flooded fields (and being the good Baptists that most of them are), couldn’t help but see all of this, simply and literally, as manna from heaven. By 2003, fishermen were shinnying up the roost trees in late afternoon, tying their monofilament nets among the branches and returning in the morning to retrieve hundreds of falcons.

Trading Slaughter For Safeguarding

“It was 2010 that I first came to this area with some birder friends, in the month of April. That’s when I first heard about the massacre,” Bano Haralu recalled as she poured us some illicit wine, Nagaland being an officially dry state. A Naga herself, Bano left the region as a young woman, earned a graduate degree in New Delhi, and became a respected television journalist specializing in India’s northeast. In 2010 she was helping the state produce a book on Nagaland’s birds, hence the trip to Doyang. She was initially skeptical of the accounts she heard—after all, in April there were no falcons to be seen. But the story stuck with her, and two years later, in autumn, she and her colleagues from Bangalore-based Conservation India returned to investigate.

We’d met Bano for dinner in a small wooden house in Pangti that serves as the headquarters for the Nagaland Wildlife and Biodiversity Conservation Trust, a nonprofit that she founded. She told us how in October 2012, she and her friends were staring in wonder at thousands of falcons perching on electrical wires by the reservoir when two Naga women happened by, carrying what Bano thought were 60 or so dressed chickens. They turned out to be plucked falcons. Later, in Pangti itself, “We saw birds in almost every home,” she said. Hundreds of plucked falcons, skewered through the head, hung smoking over fires; hundreds more, alive, were jammed into zippered mosquito nets that functioned as holding cages until they, too, could be killed. Trapping and selling falcons had become a universal cottage industry.

A typical Pangti kitchen, where the author enjoyed hearty meals of dhal, sticky rice, long beans, squash, and seasoned pork. Photo by Kevin Loughlin.

In years past, people collected and sold thousands of Amur Falcons as food for cookpots—but recognition of the birds' value as a natural spectacle has led to efforts to conserve them. Photo by Kevin Loughlin.

“It was overwhelming, you know. You don’t know where to start, what to do, what to say, how not to offend people, not create a scene,” Bano told us. But as the daughter of a decorated government official and a noted social activist, she knew how to get results. She called the district commissioner, prompting an official order reinforcing formal protection for the birds; the forest department deployed guards to enforce it, and a few arrests were made. It was clear that government authorities would no longer turn a blind eye to the killing, which was officially illegal.

That was the stick, but in the months that followed, conservationists presented the carrot to village leaders as they described the global migration of the falcons—and the worldwide revulsion expressed at the slaughter in Nagaland. Then Conservation India and the local wildlife trust launched a massive, multipronged community educational campaign with funds, materials, and support from BirdLife International, the Wildlife Conservation Society, the venerable Bombay Natural History Society, and other conservation groups. Conservationists started eco-clubs for children in Pangti and surrounding communities and gave “Amur Ambassador Passports” to those who pledged to protect the birds.

An Amur Falcon local-pride effort followed the same model that has worked elsewhere for other threatened birds in need of a PR campaign. Publicity events such as falcon-celebration festivals brought in governmental dignitaries to issue “Falcon Capital of the World” proclamations while choruses of schoolkids sang pro-falcon songs they had written themselves. Amur Falcon posters were plastered throughout the region. Baptist ministers were persuaded to preach pro-falcon sermons and conduct special church services, and villagers were given “Friends of the Amur Falcon” buttons. The former trappers and hunters formed the Amur Falcon Roost Area Union, which posted guards, certified guides, and worked with the landowners of the roosts to build viewing towers like the one we’d visited.

Betting on Birders

None of this obscured the fact that the community had taken a financial hit when it suspended the hunt. Villagers were able to sell four of the falcons for 100 rupees, Bano said, a little more than $1.50—a sizable amount, since just eight falcons would equal roughly a day’s wages in the region, and trappers were selling thousands a day at the peak of the season. For Pangti as a whole, the end of falcon-trapping meant foregoing about 3.5 million rupees annually, a huge sum in such a remote, cash-strapped area, especially because many people used that money to pay their children’s school fees.

One of them was Nchumo Odyuo, a slender, soft-spoken man who is a neighbor of the Tsopoes, a former trapper now active in the protective union. Losing the money from selling falcons was hard, he told me one morning as we watched hundreds of Amurs flying in to perch around the edges of a small teak plantation, some miles from the main roost; the birds preened in the sun, and occasionally dropped to the ground to snag large mantises or grasshoppers. Nchumo and his wife have several children at home, and two older kids at boarding school, the only choice for more than a grade-school education.

The villagers suffered a double blow, he told me—first they had lost much of their best farmland for the dam, then the trapping was taken away.

“At first [the residents] were angry, because the government has not compensated us. But slowly, we have understood. I am glad the falcons are protected. But I do wish I could eat one!” He laughed nervously. “They taste very good.”

“It was a huge loss of money,” Bano admitted, but some in the village saw the potential for tourism. Several families in Pangti invested in improvements so they could take in visitors; the Tsopoes, with whom we were staying, built a two-stall, Western-style bathroom in their side yard, and a dirt-floored washroom with a sink. (The Wildlife Trust of India built a small guest house in Pangti in 2017, but it wasn’t yet furnished or ready by the time of our visit.)

While the falcon trapping benefited most of the community, the new tourism-based paradigm helps a narrower segment, said Deven Mehta, a junior research fellow at the Wildlife Institute of India who is studying the diet of the Amur Falcons near Pangti. The primary beneficiaries now are guides like Nchumo; landowners like Nchumo’s uncle, on whose land the watchtower sits; and families like the Tsopoes who had enough extra cash to invest into creating homestay operations.

A lack of community-wide equity is a major problem, Mehta believes. And even with incentives, there is no guarantee that people will make the best long-term decisions. Since the last falcon season, Mehta said, trees on the edge of the main roost grove had been cut down to plant teak seedlings—a common agroforestry practice here, but one that obviously could threaten the whole local operation were the falcons to abandon the Pangti roost for a less disturbed site.

Although Pangti is far from the tourist track, we were pleasantly surprised to find we weren’t the only visitors. During our stay a few small groups from elsewhere in India—in twos and threes, and most (to judge from their lack of equipment) not birders—showed up at the watchtowers. An Indian documentary filmmaker and his friends spent several days, as did a large, enthusiastic birding group from Bangalore in southern India. I struck up a conversation with one of them, Ulhas Anand, and discovered we had several mutual birding friends from his time living in Philadelphia.

“The birding in Bangalore is incredible. We have some very bird-rich areas. But nothing like this,” he said, gesturing to the multitudes of falcons emerging from their roosts. Then he was gone—someone had spied a Philippine Brown Shrike along the edge of the lake.

In most wild parts of the world, conservationists abhor new roads. But Bano Haralu and others are glad there’s a road to Pangti, and they wish it was nicer. They see the awful condition of Nagaland’s roads–often cited as the worst in India—as a major hurdle to conservation, and the tourism that could support it. The peak of the falcon migration neatly coincides with the seasonal, post-monsoon opening of Kaziranga National Park in neighboring Assam state, a UNESCO World Heritage site that attracts visitors from around the world. (And for good reason: A week later, looking out on Kaziranga’s grassy floodplain, I counted 59 Indian rhinoceroses in a single, wide sweep of my binoculars, as wild elephants, buffalo, wild hogs, and swamp deer grazed and Pallas’s Fish-Eagles soared overhead.) Combining the two sites would be an ecotourism no-brainer, if the travel time between them was a couple of easy hours on a well-paved road instead of the bone-grinding, eight- or nine-hour marathon that travelers face now.

A Safe Place to Roost

Although the greatest spectacle in pangti was the morning liftoff, one evening we returned to the roost area at dusk, hoping to see the falcons come in for the night. Hiking down to the reservoir, we passed trails pushed through the dense vegetation—the paths of wild elephants, perhaps the same ones we’d heard trumpeting across the lake that morning. Songbirds flitted about in the failing light—White-browed Scimitar-Babblers, all lanky and brown; pairs of Red-vented Bulbuls; flocks of hyperactive Yellow-bellied Fairy-Fantails.

About 45 minutes after sunset, falcons began streaming in—first hundreds of birds a minute, then thousands, a sheet of movement against the band of orange and purple light on the west ern horizon. We were near the convergence of a great inrushing of wings and movement, coming from all points on the compass, like a black hole drawing everything toward itself. The falcons flew with smooth, languid wingbeats, mostly gliding toward the roost trees, the morning’s shivering noise of tens of thousands of rising wings replaced now with an almost eerie silence.

For now, the falcons are safe—not only in Pangti, but across Nagaland. The combination of more rigorous law enforcement and pervasive education campaigns has proven so effective that conservationists were unaware of even a single bird being trapped during the past several migration seasons. As interest in the Amur Falcon spreads throughout northeast India, reports have emerged of other major roost sites in neighboring states such as Assam and Manipur—and local movements in those places, as well, to end hunting and to protect and celebrate the raptors. Tourism is building slowly, as we saw. But Kevin plans to be back this autumn with a full group of Americans (and mattresses for their beds) to buttress the nascent industry.

The intensity of the flight only increased with darkness, as a nearly full moon rose overhead. The white disk flickered and trembled with black silhouettes as falcons beyond count came home to roost, their bellies full and their instincts already pulling them toward the next stop on a global journey that—at least here, at least now—is not as dangerous as it was just a few years before.

Scott Weidensaul is a naturalist and Pulitzer-nominated author of more than two dozen books about natural history.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you