This Could Be the Winter You Get Evening Grosbeaks at Your Feeder

By Marc Devokaitis

November 6, 2018

At the end of September, three birders in Cape May, New Jersey, got a preview of what’s shaping up to be one of this winter’s birding highlights. It took the form of 1,570 Red-breasted Nuthatches flying past the group during a single day—the highest single count for the little cinnamon-and-gray acrobats ever reported to eBird.

“I think we’re in store for our best widespread multi-finch invasion in several years” in eastern North America, says Matt Young, a finch expert and the collections management leader at the Cornell Lab’s Macaulay Library. (Young knows nuthatches aren’t finches, but says their movement patterns are so similar that he considers them “honorary finches.”)

“We’re already seeing Pine Siskins in a few spots along the Gulf Coast, and Red-breasted Nuthatches all the way into Florida,” he says. That’s well south of these two species’ typical ranges. Elsewhere, a birder in Long Island counted nearly 2,700 Pine Siskins and more than 2,200 Purple Finches on the move in a single morning in late October.

Following in the wake of these waves of early migrants could come Common Redpolls, Evening Grosbeaks, Bohemian Waxwings, and possibly even Pine Grosbeaks, according to Ontario-based ornithologist Ron Pittaway. For the last two decades, Pittaway has painstakingly compiled notes on crops of conifer seeds and berry-producing trees from around the boreal forest to produce a “winter finch forecast.” By surveying the food supplies in these birds’ normal winter range, he can detect years when food crops in eastern Canada fail (like this year) causing those northerly denizens to flood into forests farther south in a movement known as an irruption. Read Pittaway’s 2018-2019 Winter Finch Forecast. (Pittaway’s forecasts don’t apply to western North America, where many finch species have regular breeding and wintering populations, and irruptions are harder to predict.)

Next Up: Evening Grosbeaks

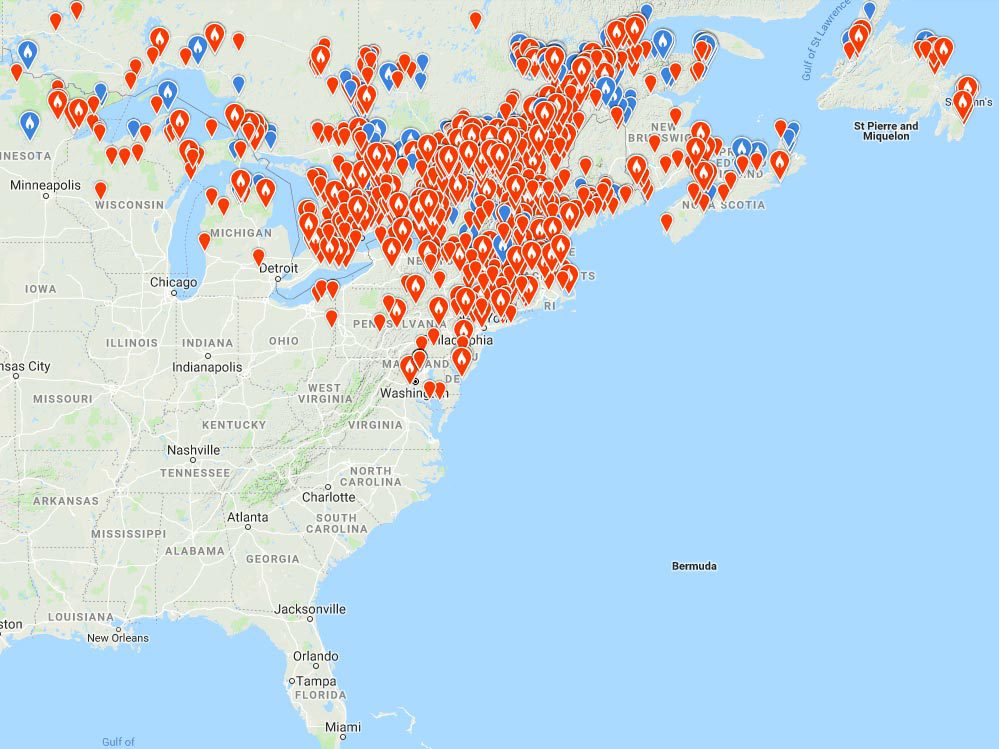

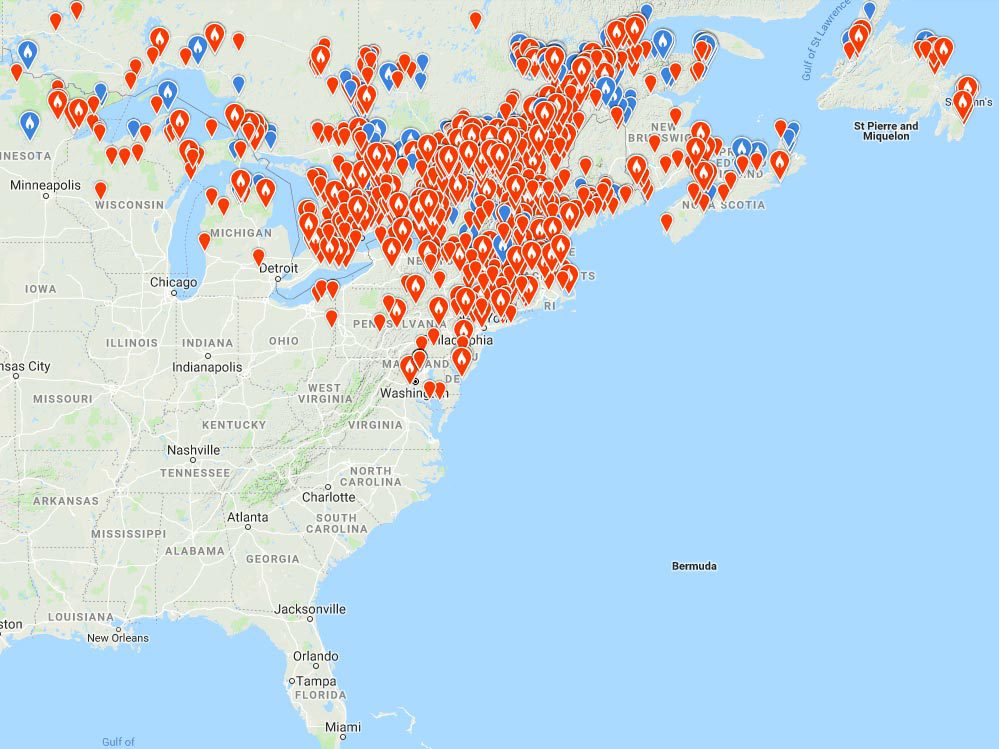

Siskins, Red-breasted Nuthatches, and Purple Finches are among the earliest movers of the winter, according to Young. He says that pulses of these species often show in early fall or even late summer—with more southerly breeding ranges, they don’t have as far to travel. But Young is also picking up signals from birds that breed farther north, and that normally don’t show up until late fall. For example, he says early eBird observations are hinting at the largest movement of Evening Grosbeaks in the Northeast in more than a decade.

“Evening Grosbeaks have a fascinating history,” says Young. “From the 1960s through much of the 1990s, they were one of the most common species seen at bird feeders across much of eastern North America in the winter. But in the past two-plus decades they’ve shown up less often and in fewer numbers. They are even listed as a species of special concern in Canada.”

Reports of the striking birds—males sporting the colors of summer sunflowers highlighted by a bold golden eyebrow, females a dusky gray with tinges of gold—have been lighting up online discussion groups of late, as birders in the East are eager catch a glimpse.

By October, Evening Grosbeaks had shown up in many spots in New York and southern New England, with a smattering of reports from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and even Maryland. Young had predicted that the Carolinas or even Georgia could see grosbeaks this year, and lo and behold: as of late December, birders in Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee had reported the species to eBird as well.

Common Redpolls are on their way too, in their biggest numbers since the “superflight” winter of 2012–13. Young says this could be one of the rare years where they travel as far south as the Carolinas. And as far south as Pennsylvania and southern New England, birders might even see a few Pine Grosbeaks—generally the rarest winter finch to reach the U.S. That sort of movement hasn’t happened since at least 2007-08 in the Northeast.

One species that Young doesn’t expect to make much of an appearance are Red Crossbills. Last year, they came south into coniferous forests in the Northeast, but he and Pittaway say good cone crops across Canada and the western U.S this year will keep many of them within their typical range. On the other hand, Young suspects moderate numbers of White-winged Crossbills and perhaps some type 10 Red Crossbills may show up in the Northeast.

How to Get Winter Finches Into Your Backyard

More on Winter Bird Feeding

Perhaps the best news is that it’s quite possible this year’s finch irruption could play out in your backyard (particularly if you live in the Northeast or Mid-Atlantic). Finches and Evening Grosbeaks flock to black-oil sunflower seeds. To attract grosbeaks, go big: while these large birds may be able to squeeze onto a tube feeder, you’ll have better results offering the seeds on a platform feeder. Common Redpolls and Pine Siskins also take sunflower seeds, but they frequent nyjer feeders too. These smaller species will feed from a variety of feeder types. Red-breasted Nuthatches are even more versatile, comfortable plucking a seed out of a hopper or hanging upside-down to work on a suet block.

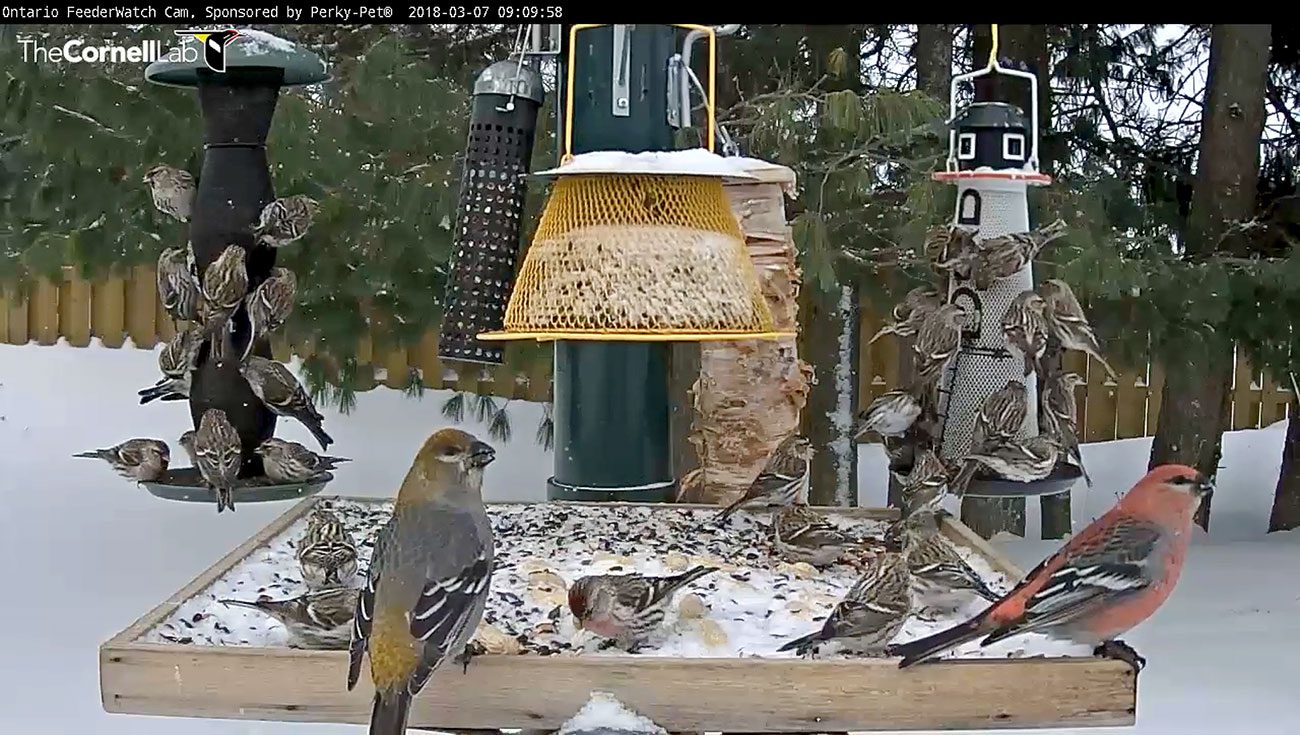

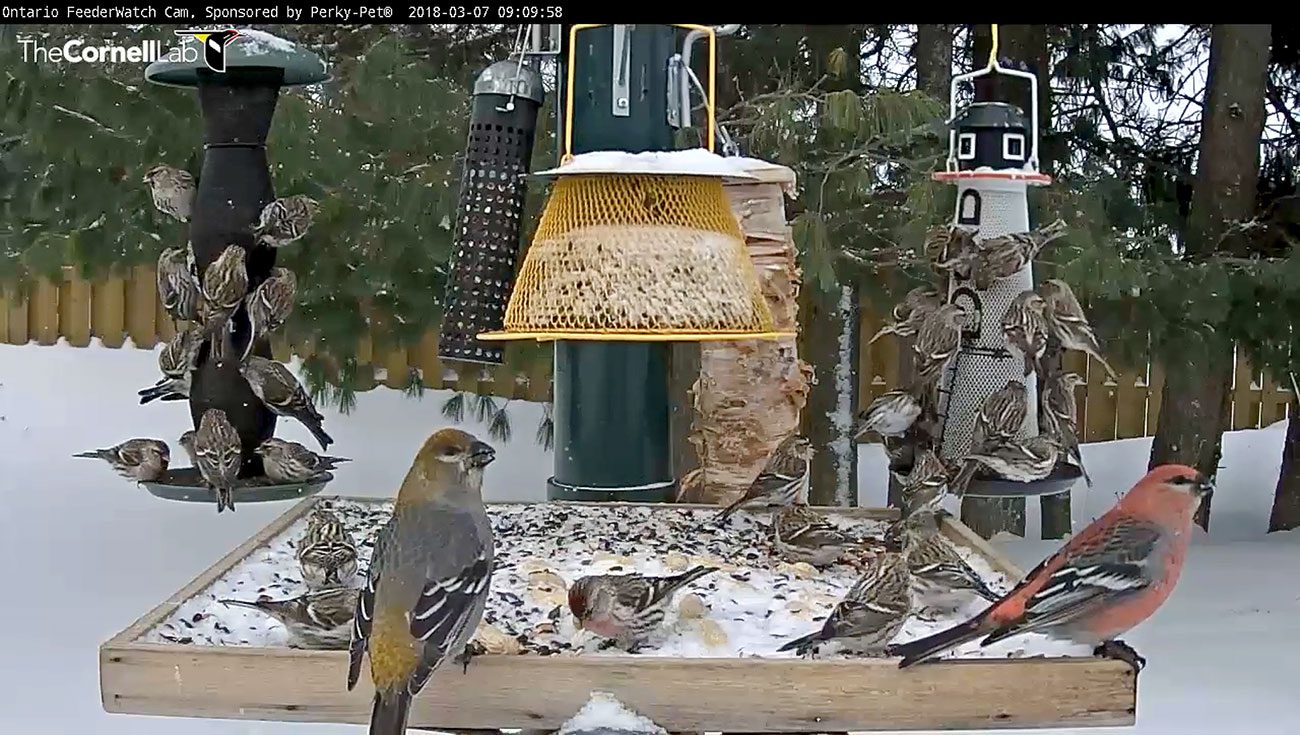

If you’re lucky enough to have Pine Grosbeaks visit your area, you may need to get out of your backyard to see them. These birds are regulars at the platform feeder on our live Ontario FeederWatch Cam—but farther south, according to Young, they don’t often visit feeders. Instead, look for them in residential areas with fruiting trees such as mountain-ash and crabapple (which are also good places to try for Bohemian Waxwings), and in forests with spruce trees, where they feed on the buds.

While you’re at it, why not join Project FeederWatch and keep track of visits from your winter birds? The data you record will help scientists keep track of bird populations, and most people find they start to notice more at their feeders than they ever did before.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you