Birding Gets the Fantasy Sports Treatment

By Marc Devokaitis

April 12, 2019

From the Summer 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Competitive “Big Years” stoke the imagination. Birder and author Noah Strycker crisscrossed the globe in 2015 and saw or heard an astounding 6,000 different species. He also shelled out $60,000 and logged over 100,000 miles in the process. But now anyone with the internet can compete in a Big Year without spending a dime or traveling a mile thanks to Fantasy Birding.

The new game, built by lifelong birder and web developer Matt Smith, pits players against each other to see who can tally the most bird species. Just like in fantasy football, players score by predicting real-world results. But in fantasy birding, the goal is to rack up the most species through virtual birding anywhere in the world.

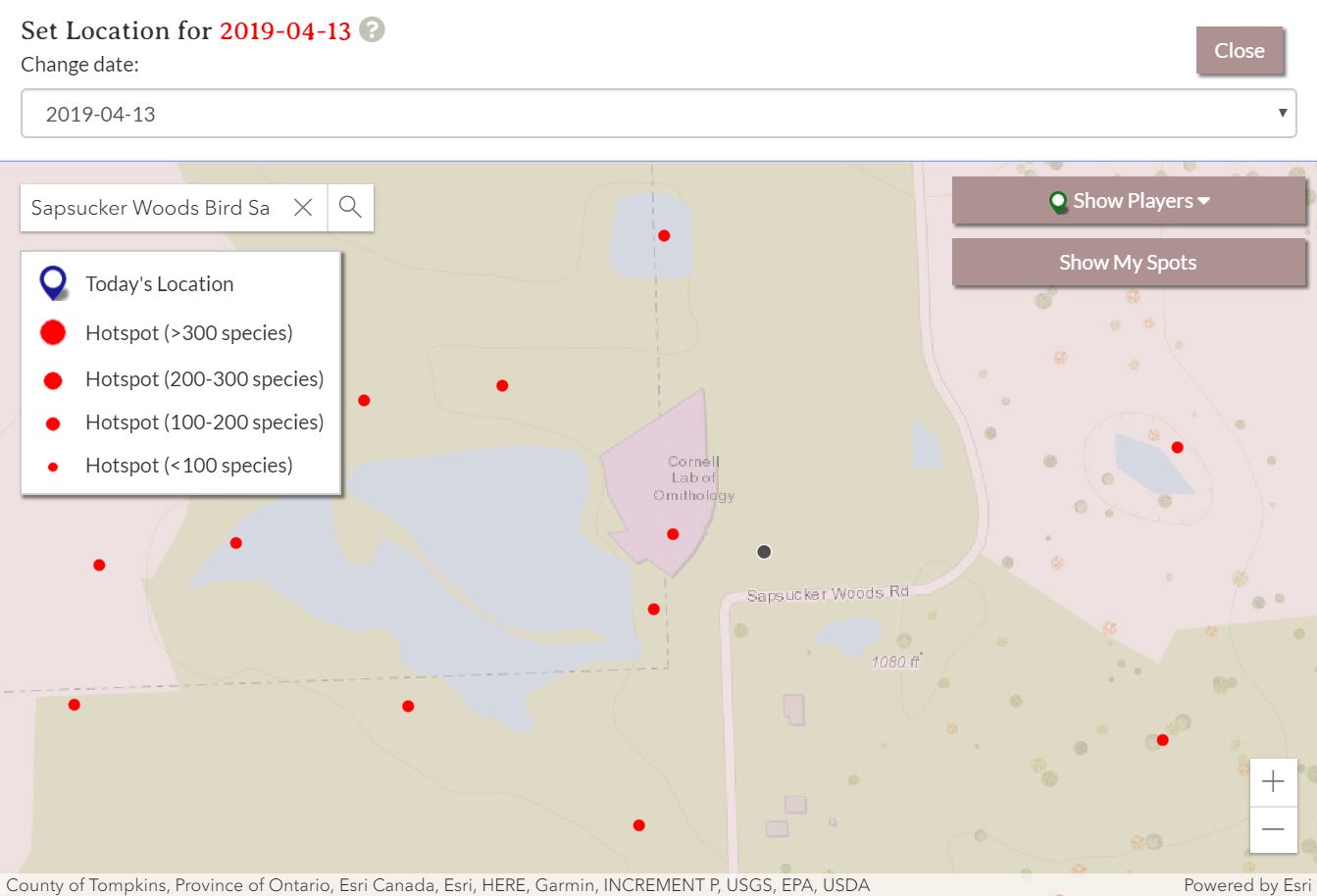

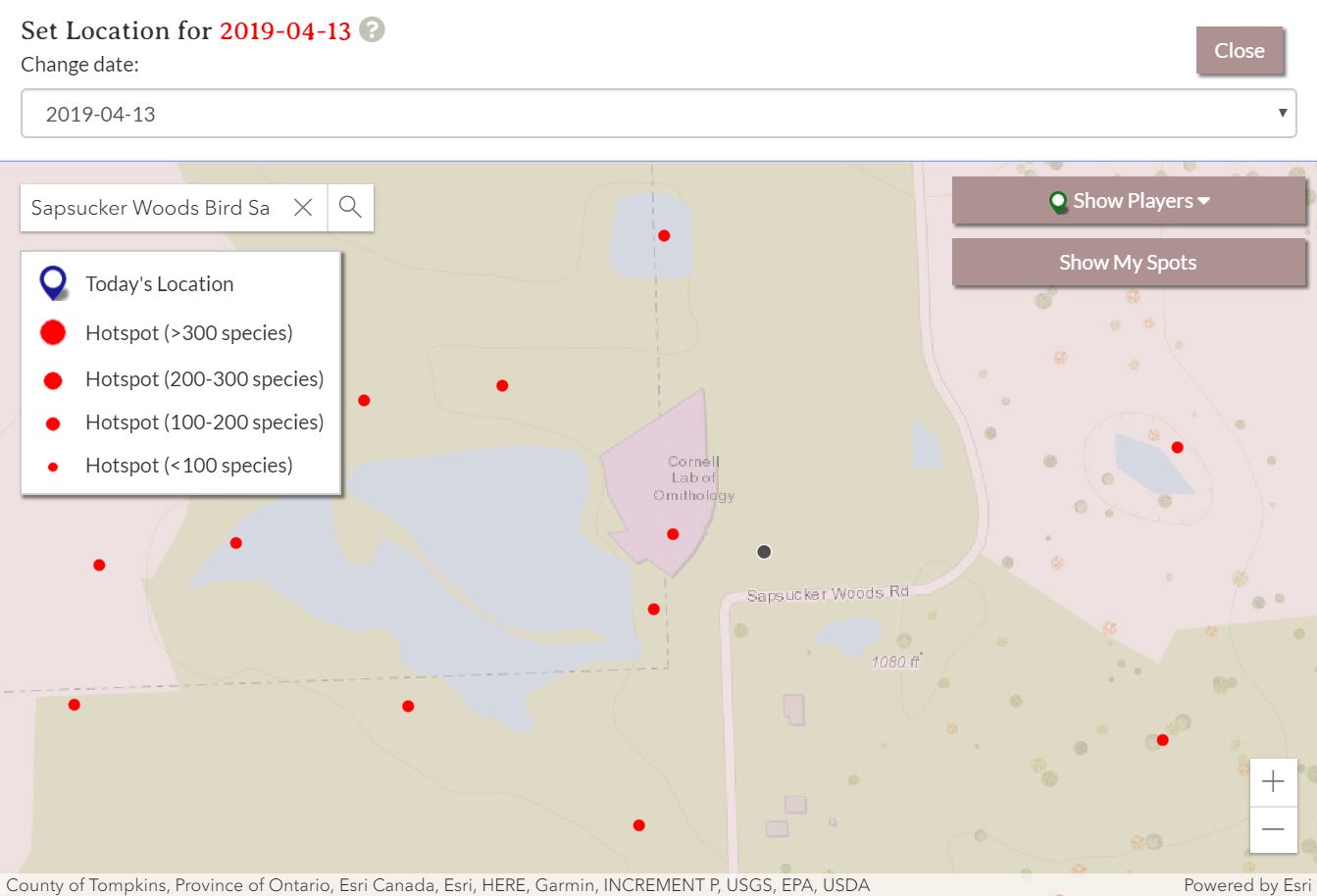

Players choose one locale per day by placing a 10-km circle on a map. Any species that an eBird user submits on a checklist from within that circle on the following day counts toward the player’s total (if that species isn’t already on their list.) Currently, there are two main competitions; one for a North American Big Year, and one for a Global Big Year.

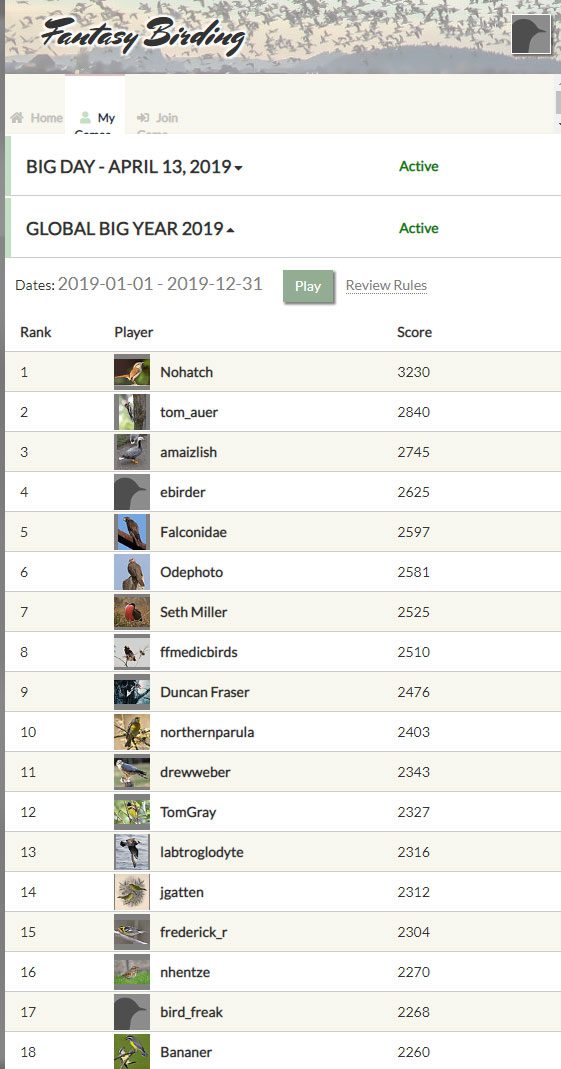

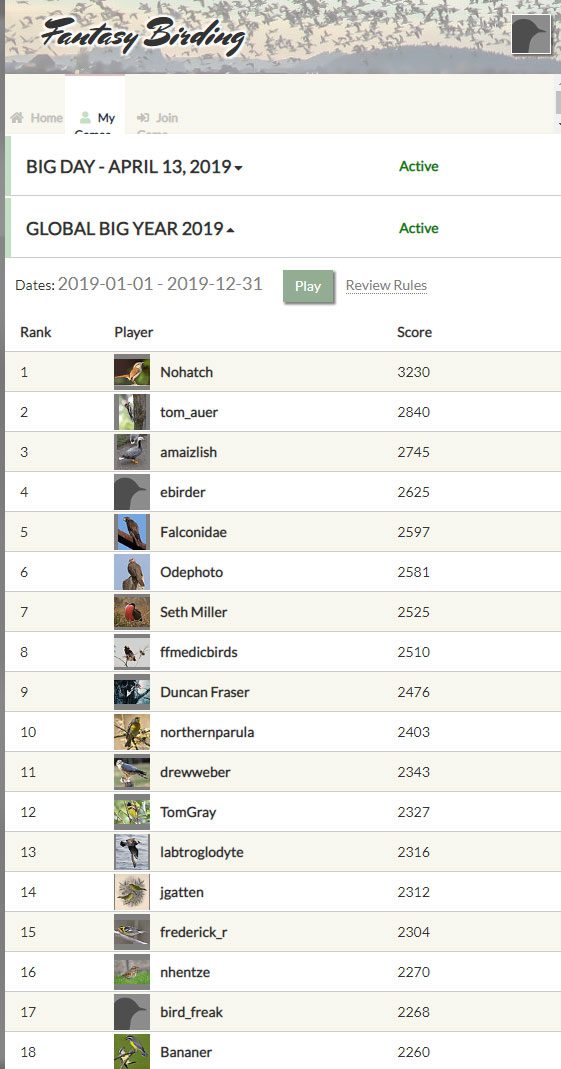

To see exactly how it worked, I set up an account for myself. I noticed a few familiar names on the leaderboard, including at least one coworker who was in the top 10. Before getting started, I paid the person a visit at their desk.

“I can’t talk too loudly about this, because I don’t want people nearby to know my strategy,” said “Ron” (not the person’s real name), an eBird team member who was in sixth place in the North American game as of this writing, with a total of 544 species.

In quieter tones the person revealed: “Right now, I’m in Alaska because my research has led me to believe there are a number of Code 2 birds west of Juneau.” Code 2 refers to the rarity designations used by the American Birding Association. Code 1 and Code 2 birds are the most common; codes 3, 4, and 5 represent increasing levels of rarity for a given location.

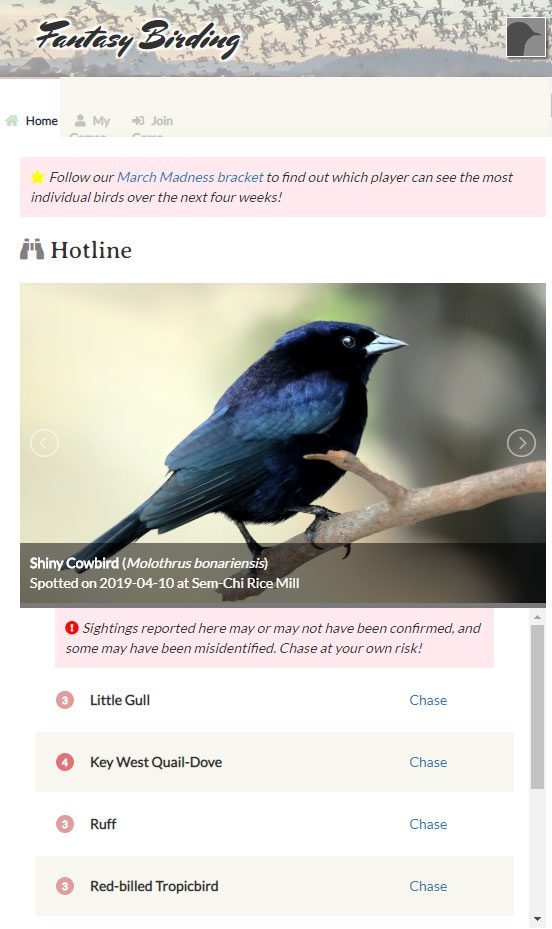

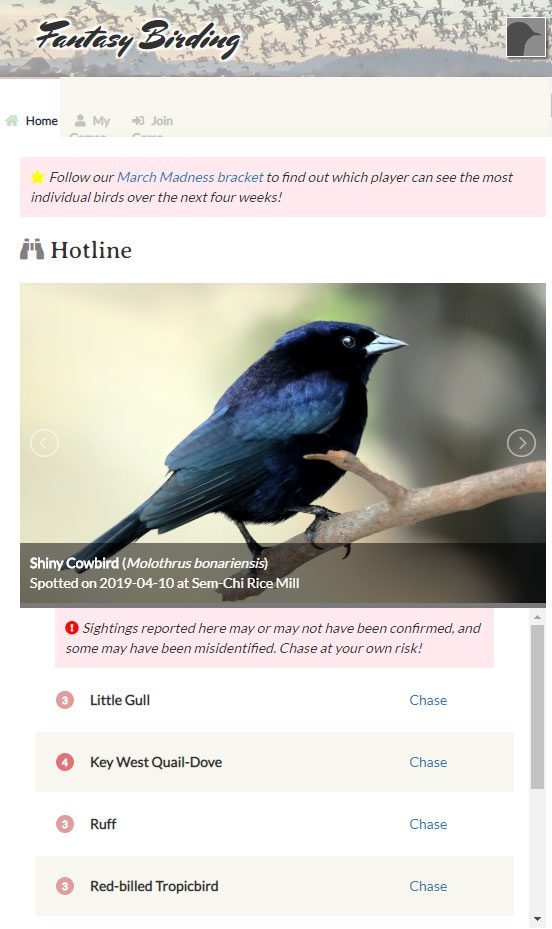

Since you can assume the serious competitors will all tick the most common species eventually, Ron says part of the challenge becomes putting yourself in the right place at the right time to capture the rarities. Players can sleuth out what rarities are being seen in different areas, set their locations, and hope that the target bird sticks around for someone to see the following day.

I’ve never been a rarity-chaser in real life, but the prospect of jumping from hotspot to hotspot, vicariously birding in sunny south Texas or southeastern Arizona during the waning days of an upstate New York winter, definitely got my birding juices flowing. I jumped into the North American Big Year game.

Even though the game has been going since January, and some folks have well over 500 species already, I figured I could quickly gain species by choosing a familiar top birding spot that I knew was frequented by eBirders: the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, in Ithaca, New York. With a couple of clicks I was set. All I had to do was wait until the next day for the birds to start rolling in—and if the mood struck, I could even duck away from my desk to do some real birding in Sapsucker Woods and help my own cause.

In my first 24 hours, my total jumped from zero to 69 species, vaulting me ahead of scores of competitors. Now I was #411 out of 588, and I had even scored a code 2 bird (a Eurasian Wigeon). For the next day, I moved my circle to the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge in south Texas. One click of the mouse and my itinerary was set—no plane tickets, accommodations, or rental vehicles needed. (After 3 weeks of play, I had moved up to #194 out of 1,000 players, with 357 species on my list.)

A few cool features elevate the game to more than just stat-watching. A satellite map of their current birding location greets players at login, along with the local time, weather conditions, and a list of recent notable birds reported from the area. Scrolling down reveals detailed descriptions of the plants, animals, and landscape features of the region. Players’ bird lists show a photo of each species and give a brief life history description, with the opportunity to click through to eBird for more information. A map shows the current birding location of every other player. If a player stays logged in, new species for their list will pop up as they are reported in nearly real-time.

eBird program coordinator Ian Davies says the game is a cool way to use the data that is constantly flowing into eBird.

“It’s a great way to get folks excited about birds,” says Davies. “It helps people think critically about where and when birds occur, and gets people excited about contributing to eBird since their fantasy lists rely on eBird checklists.”

Smith agrees, and adds that he’s also heard from multiple players who have taken up Fantasy Birding because they aren’t able to get out and bird in the real world for various reasons: “Some are raising kids…others are caring for older parents – and some are not of driving age yet! That’s what’s given me the most joy – giving folks like this a taste of the thrill of birding at the highest level.”

And while the majority of players are real-life birders, there are some who started playing out of sheer curiosity, without any prior bird knowledge.

“There’s a wholesale grocery business in New Hampshire where about a dozen people have created an informal Fantasy Birding league, and are trading trash-talk around the office about the birds they’ve ticked,” says Smith. “So I’m very hopeful about using this platform to spread the good news about birds, and to turn more people on to the value of this kind of data.”

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you