Celebrities, Strangers, and Friends: What Google Searches Tell Us About How People Relate to Birds

By Kathi Borgmann

April 15, 2019

From the Summer 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

“Wouldn’t it be cool to see what bird species people googled more often?”

That’s the question scientist Justin Schuetz posed to Alison Johnston, a researcher from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Curious about the answer, they decided to find out—by examining the past decade of Google Trends and eBird data. Their results, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, uncover four different ways that people relate to birds in North America—and may help with new approaches to conservation.

Google Trends data—the information Google tracks for every search word entered into its search bar—provides a fascinating look into people’s interests, and what’s popular. In 2018, World Cup was the number one search term on Google, followed by Hurricane Florence, YouTube personality Logan Paul, the Keto diet, and how to register to vote. All these words reveal a little bit about what’s on the minds of millions of people in the United States. When that analytical frame is applied to birds, Schuetz, the lead author of the study, says it “provides a snapshot of people’s interest in species.”

Johnston says their original goal “was to look at which species people googled, but we realized that people probably more often google birds that they encounter frequently.” To look beyond this basic pattern at what makes some birds especially interesting while others garner less interest, Schuetz and Johnston examined 10 years of Google Trends data and more than 15 million eBird checklists submitted by citizen scientists from 2008 through 2017.

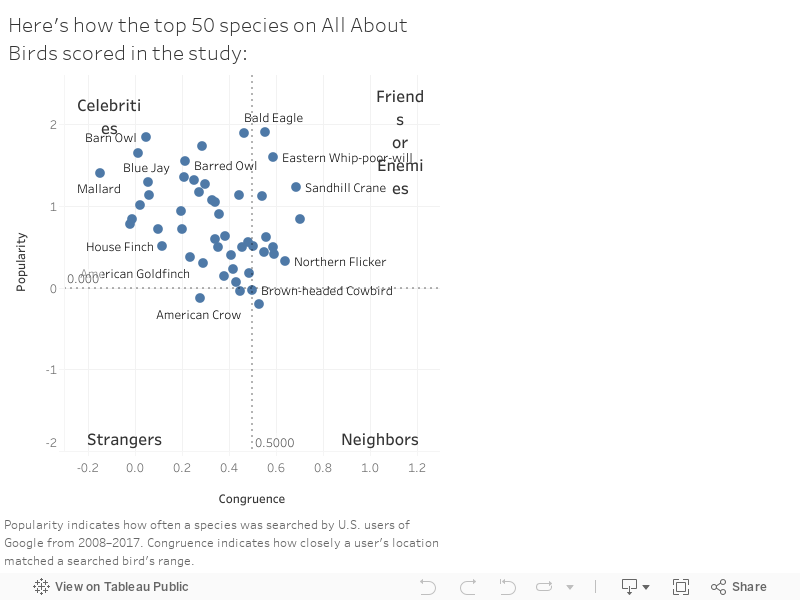

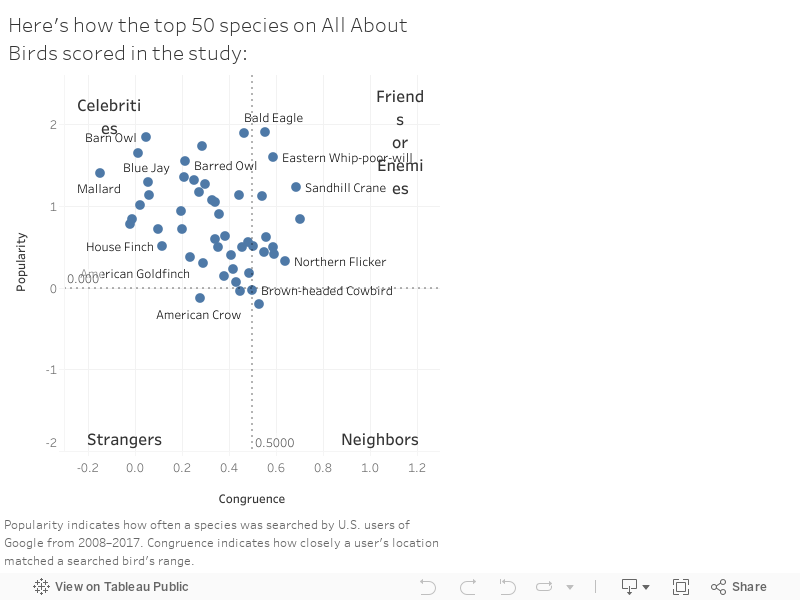

Their results grouped the most-googled birds into four categories, which the scientists called a “cultural niche space” based on how frequently people searched for the species relative to how often they might encounter the species near where they live:

- Celebrity Birds—The rock stars of the bird world that attract a lot of interest, and not just in their hometowns. Examples include owls (the most highly googled bird family of all), raptors, and sports mascots such as the Baltimore Oriole. Celebrities also tended to be bigger birds, such as the Great Blue Heron.

- Friends or Enemies—Birds that Americans google frequently, but only in areas where the species occurs. Examples include federally protected species, such as the California Condor and Greater Sage-Grouse, that catch the attention of locals. Why is this group called friends or enemies? “Trends data can only tell us what people are looking for; we can’t get at motivations,” Schuetz notes. Even so, Johnston says that from this pattern of local interest “we can start to understand why some species garner more attention than others … which will help us make stronger conservation decisions.”

- Neighbors—Birds that inspired search queries, but only from Americans that lived nearby. Examples include the Gila Woodpecker of Arizona and Black-crested Titmouse of Texas.

- Strangers—Birds that most Americans have yet to discover, such as shorebirds and “little brown birds” such as Lincoln’s Sparrow.

Beyond these categories, Schuetz and Johnston also noted that how often people searched for species varied by a bird’s family, size, migratory status, and association with feeders. The effect of size may be because larger species grab people’s attention, which could help explain why Great Blue Herons or Turkey Vultures are targets of searches more often than smaller species like Northern Mockingbirds or Brown Creepers.

Explore a graph of all 600+ species results at researcher Alison Johnston’s website.

When it comes to communicating the value of a species to the public, conservationists have previously focused on either a species’ intrinsic value (as a uniquely adapted organism), or its monetary value in terms of services the species provides to ecosystems or economies. Schuetz and Johnston took a different approach.

“Our motivation was to get outside the notion of monetary value,” which can be difficult to establish, Johnston says. But, she adds, conservation shouldn’t be a popularity contest, either. “Our research is not about who won or who lost, but about how people engage with the natural world.”

“It takes more creative messaging to get people to care about the poorly known species,” Schuetz says, but there are ways. For example, “local conservation groups might want to identify species that are regionally well known but don’t have a reputation beyond that region. These species could be good candidates [for] regional pride and stewardship programs.” It’s all a matter of staying relevant to an ever-changing audience, he says—perhaps another reason to pay attention to Google Trends.

Reference

Schuetz, J., and A. Johnston (2019). Characterizing the cultural niches of North American Birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1073/pnas.1820670116

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you