Are Woodpeckers Evolving to Look Like Each Other? A New Study Says Yes

By Marc Devokaitis

June 17, 2019

From the Summer 2019 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers are a classic case of confusing species. Both woodpeckers sport similar black-and-white plumages, males of both species don a red mark on the back of their heads, and the two species’ habitats and ranges overlap considerably.

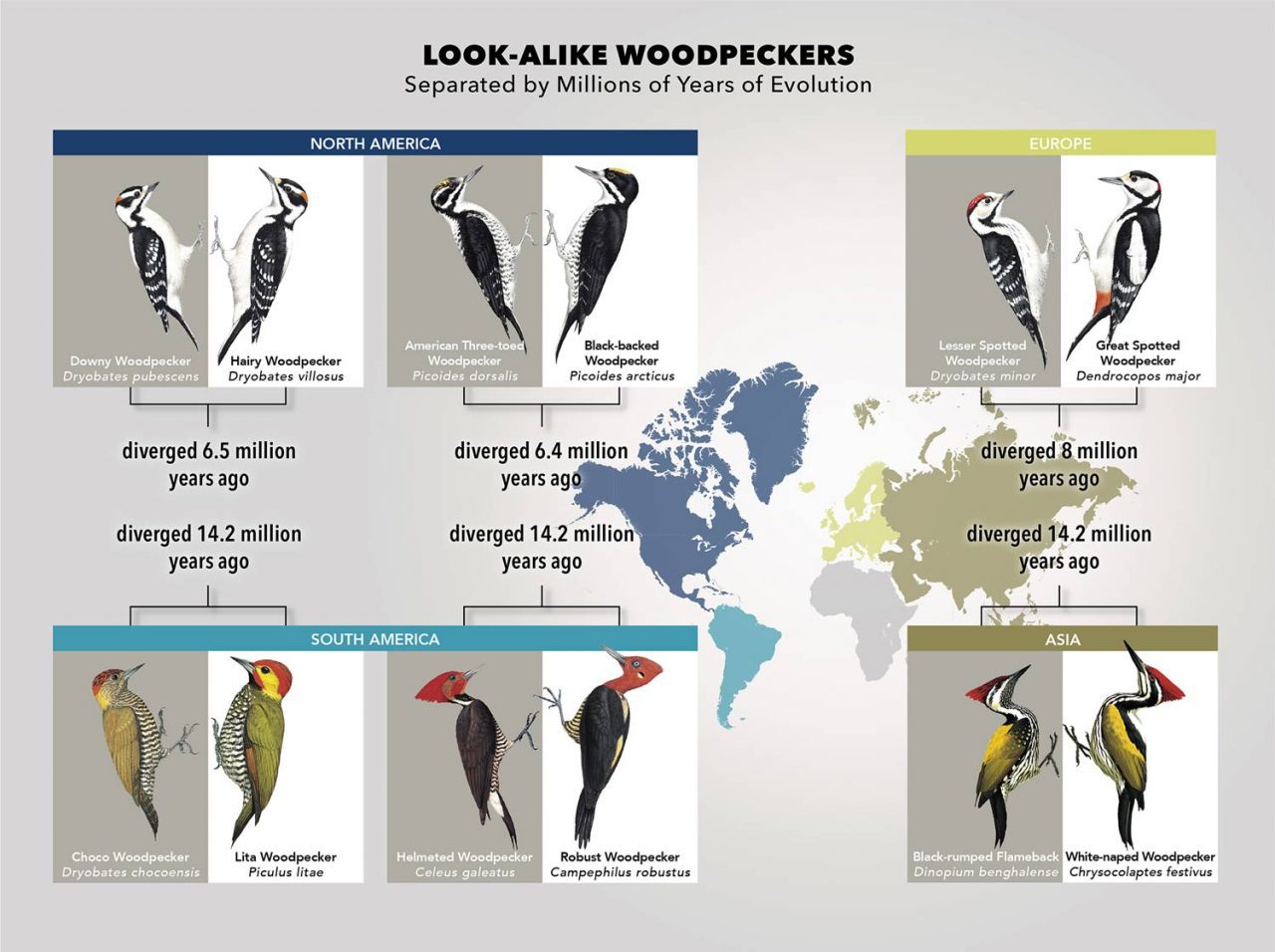

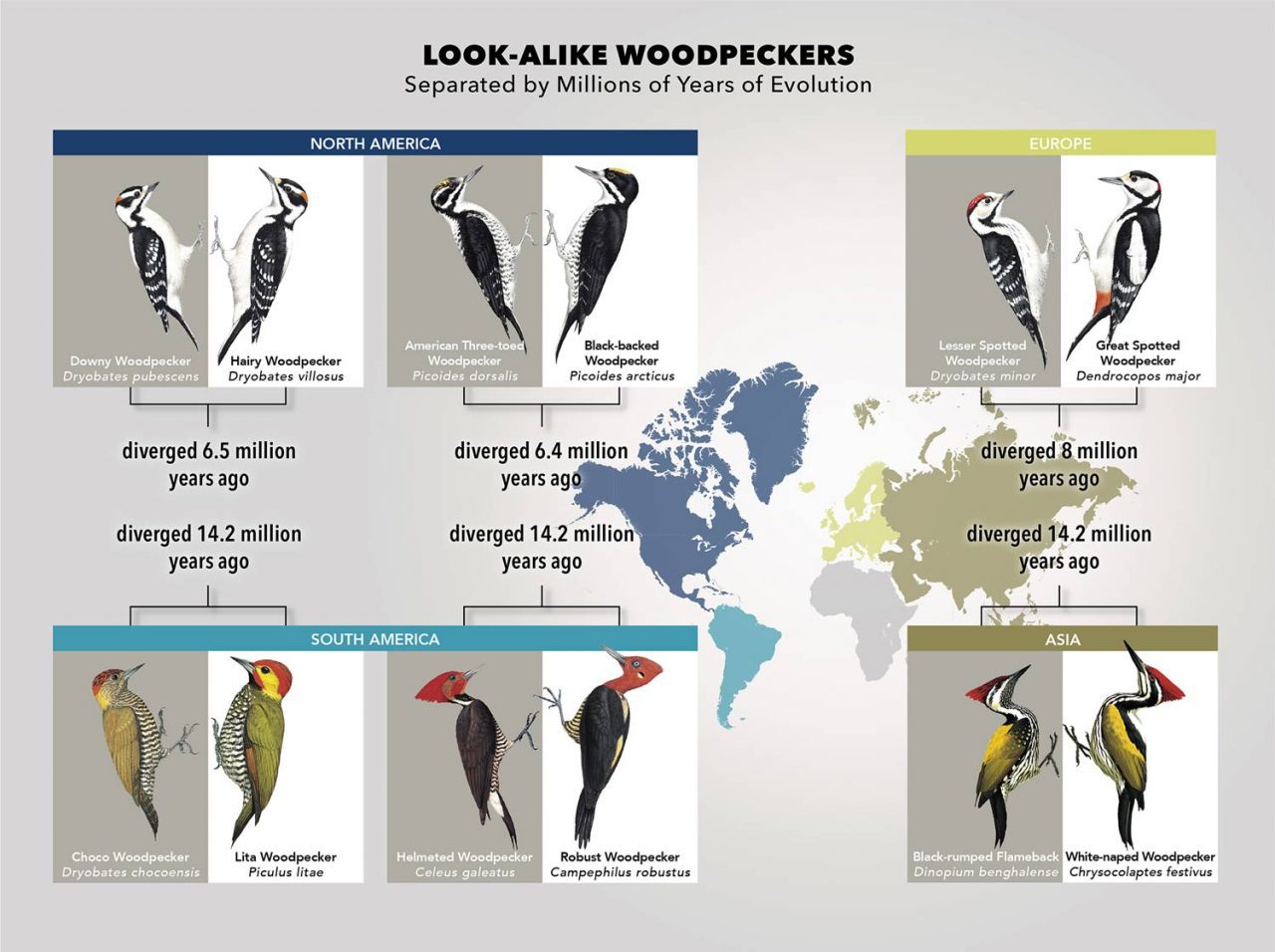

But despite being look-alikes, these two species are not that closely related. Their genetic lineages split off from a shared ancestor over 6 million years ago—about as far back as chimps and humans split. The Hairy Woodpecker is more closely related to the very different looking Red-cockaded Woodpecker, while the Downy is closer to Nuttall’s Woodpecker.

A new study published in April in the journal Nature Communications provides strong evidence that Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers are an example of “plumage mimicry”—one species of bird evolving to match the plumage patterns and colors of another. And the researchers found more instances of woodpecker doppelgangers all around the world, including Lesser Spotted Woodpeckers that look like Great Spotted Woodpeckers in Europe; and Cardinal Woodpeckers that look like Gabon Woodpeckers in Africa.

“Other researchers have noticed these pairings before, but this is the first time anyone has tried to conclusively demonstrate that these similarities are true mimicry,” says Eliot Miller, lead author of the study and collections development manager at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library.

The new study sought to explain how it is that the Downy and Hairy Woodpecker, or the White-naped Woodpecker and Black-rumped Flameback (two Asian species that resemble Pileated Woodpeckers painted with a strip of gold), can look nearly identical even though they have been evolving separately for millions of years. Miller and his colleagues compared 230 woodpecker species across the globe. For each woodpecker pairing, they tested how strongly genetics, habitat, climate conditions, and geographic proximity correlated to similarities in plumage patterns.

After comparing millions of eBird observations, satellite readings of habitats, and complex color and pattern measurements of the woodpeckers, their results showed that geographic overlap—sharing ranges—was a better predictor of look-alikes than genetics, habitat, or climate.

“The fact that the strongest correlation for these look-alikes was range overlap, rather than any of the other possibilities we looked at, strongly suggests there is mimicry happening,” says Miller.

Mimicry occurs when one species evolves to look like another species because of the social interactions between the two. In most cases, mimicry conveys some advantage to the species that is doing the mimicking. Classic examples include flies that evolved to look like stinging bees and nonpoisonous butterflies that evolved to look like toxic butterflies.

Miller’s study was focused on identifying whether (not why) plumage mimicry is occurring among woodpeckers. But he does have a theory on what’s driving these distant-cousin woodpeckers to look like identical twins. Miller suggests that the smaller, more passive of the pair might evolve to look like the larger, more aggressive bird to discourage predators, or to intimidate competition. A nuthatch or a titmouse might think twice about competing with a Downy Woodpecker at the bird feeder if it thinks it’s going up against the more formidable Hairy Woodpecker. (Previous research using Project FeederWatch data ranked Hairy Woodpeckers much higher than Downy Woodpeckers in terms of dominance.) Miller says field experiments would be needed to more conclusively test this hypothesis.

The data also turned up some other interesting connections between woodpecker appearance and habitat. Many tropical woodpeckers have darker feathers, adding evidence to support “Gloger’s rule,” the theory that animals in humid environments tend to be darker than their counterparts in drier climes. They also found that woodpecker species with red heads tend to live in forested habitats; black, white, or gray species tend to live in open habitats; woodpeckers with red on their bellies are most often found in forests; and woodpeckers with large patches of color on their bellies are most often found in open habitats.

“By looking at what drove these woodpeckers to look like one another, not only have we demonstrated mimicry in birds, but we have learned a great deal more about what’s behind the plumage patterns of some species,” said Miller.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you