How Ron Pittaway Developed His Acclaimed Winter Finch Forecast

By Hannah Hoag

January 9, 2020

From the Winter 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

In early February of 2019, WhatsApp birding groups in southern Ontario were firing off finch alerts. More than a dozen Pine Grosbeaks spotted in Durham, northwest of Toronto. Evening Grosbeaks at Long Point, on the northern shore of Lake Erie. A flock of redpolls around Point Pelee on Lake Erie.

Ron Pittaway was ready. In the yard of his home in the northeastern corner of Toronto, he had his feeders filled with oil-rich nyjer seed and a buffet of sunflower and safflower seed, peanut butter and suet spread across his tree-studded urban property.

“See those big conifers? That’s an important finch tree, especially for siskins, and we have a whole ravine full of them here. This forest over here is full of eastern hemlocks,” he said.

During short, cool days, the cheery jewel-toned winter finches are a welcome addition to a cold season that is often bleak and gray. But their winter whereabouts can be somewhat erratic. Some years there are few to no grosbeaks or siskins, crossbills or redpolls to be found. Other years, they descend en masse to bird feeders across southern Canada and the U.S., decorating wintry backyards like yellow and red ornaments flitting about the trees.

Pittaway is North America’s principal prognosticator of when and where—and importantly, if—these birds will arrive each winter. Birders eagerly anticipate the latest edition of his annual Winter Finch Forecast, released every autumn for the past 21 years. Last winter, he bolstered his winter-finch bona fides by predicting the waves of grosbeaks and redpolls descending south four months before those WhatsApp alerts.

Pittaway has made it his mission to lend some predictability to winter finch sightings by compiling intelligence from his network of naturalists across Canada and the U.S. and analyzing the data to reveal his predictions. The annual reports have made him a bit of a celebrity among eager winter birders.

“There’s an air and a mystique about it,” says Matt Young, a Cornell Lab of Ornithology scientist who studies crossbills and contributes to Pittaway’s data collection. Young is also an avid birder.

“Ron’s Winter Finch Forecast is one of the most eagerly anticipated events of the year, like Punxatawney Phil and his shadow. But better, because instead of shadows, Ron sees winter finches.”

Although he calls one of North America’s largest cities his home, Pittaway’s life is deeply immersed in the boreal forest and its birds. He worked for decades as an Algonquin Provincial Park naturalist and natural resources college instructor. Now retired and in his 70s, Pittaway lives in a modest split-level house on a street named after a complex forest organism (lichen) that he shares with his partner—and one of Ontario’s best-known birders—Jean Iron.

The house’s windows are freckled with shiny stickers and CDs to deter birds from flying into them. The rest of their home is stuffed with bird books, avian throw pillows, owl figurines, a framed print of a Great Horned Owl by Canadian artist-naturalist Robert Bateman, and two stuffed owls—a Great Horned Owl and a Great Gray Owl. In the kitchen is a collection of mugs decorated with illustrations of Black-headed Gulls and golden-plovers. Hundreds of books—such as Warblers, Birds of Ontario (vol. II), and The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior—line the shelves and lie stacked on flat surfaces. Binoculars rest near the windows.

Pittaway has been captivated by birds for as long as he can remember. He grew up in rural Aylmer, Quebec, a town about 10 miles west of Ottawa. In the 1950s, while other kids were chasing garter snakes, he and his brother would track birds.

“We would hear the bird or see the bird, let’s say the coo of the Mourning Dove, and look for it, and sooner or later find its nest,” said Pittaway. “We went crazy over it.”

Soon he was looking up birds in books. As a teenager, he joined the Ottawa Field-Naturalists’ Club and was reading birding columns in Ottawa’s two newspapers. He began to visit the old National Museum of Canada in Ottawa (now the Canadian Museum of Nature), where he would walk among the cases of bird specimens and eggs. There, he met Earl Godfrey, the head of ornithology and one of Canada’s foremost ornithologists of the 20th century. Godfrey, who wrote The Birds of Canada in 1966, and his colleagues took him “under their wings,” said Pittaway. “I could always consult them if I needed an expert opinion.”

Pittaway longed to become an ornithologist, and even studied Latin in high school to learn the species names. But he had a hard time academically.

“I wasn’t really a good student because I was more interested in roaming the woodlands,” said Pittaway. Instead he earned a technical diploma in forestry from a local college.

In 1970, when he was 23 years old, Pittaway went north to the Canadian Arctic to work on a Snow Goose research program. The two morphs of the species—white and blue—appeared to be interbreeding, and government biologists wanted to know the implications for the population. Pittaway was one of many temporary bird surveyors hired for the study, which involved living at the edge of the goose breeding colony and monitoring the mating patterns, measuring eggs, and marking the young after they’d hatched.

The group was soon joined by a British scientist, Ian Newton, whose real interest was finches.

“We were trying to figure out the morphs of the Snow Goose…but Ian was always asking me, ‘When you see a flock of Pine Grosbeaks, how many are there?’” recalled Pittaway. Two years later, Newton published his book, Finches.

“I got it immediately. It’s really detailed on irruptions and food types,” Pittaway said. “It’s a classic, and even though it was published in 1972, it’s totally relevant today.”

Pittaway returned to Ottawa where, during a Christmas Bird Count, he met Dan Strickland, then the chief naturalist at Ontario’s Algonquin Provincial Park. At the time, Strickland happened to be hiring to fill positions for the park interpreter program.

“I was always on the lookout for the best and the brightest, and Ron Pittaway certainly fit that bill,” says Strickland. He asked Pittaway if he had ever thought of applying for a job as a park naturalist, but Pittaway couldn’t see himself in the role.

“I was an introvert,” Pittaway said. “I didn’t think much about it until March the following year when a formal letter arrived.”

It was a job offer with an inquiry about his measurements so that the park could order him a sharp, crested, official park staff uniform. He started the following month.

“I was scared and didn’t want to do it,” Pittaway recalled. “But it was the best thing that I ever did.”

Pittaway worked in Algonquin Park for the better part of 10 years, living in the staff house. One winter, he rescued an injured adult male Pine Grosbeak. He named it Mope, the folk name for the bird in Newfoundland, and fed it sunflower seeds, tree buds, and mountain ash fruits. Mope lived with Pittaway at the staff house for several years. One winter Mope’s calls drew other Pine Grosbeaks to his enclosure. The bird stayed with Pittaway in Algonquin the rest of its life, and to this day, the Pine Grosbeak is Pittaway’s favorite winter finch species.

Each birch catkin contains hundreds of tiny winged seeds that are a winter feast for Common Redpolls. Photo by Marie Read.

Evening Grosbeak feeding on seeds of an ash tree. Photo by Marie Read.

While Pittaway lived in Algonquin Park, he noticed that winter finches were not in abundance at the park’s many bird feeders every winter.

“It can be a long, cabin-fever type of winter if you don’t have the colored finches,” he said.

It was at Algonquin that Pittaway first began making a connection between the summer cone crops of cedars, spruces, and pines and the abundance—or scarcity—of siskins, crossbills, and grosbeaks in the winter. If there were no cones on the trees, it was a quiet winter at the feeders. Gradually he started to make predictions about the winter finches based on what he saw during the summer on coniferous trees, and shared his observations in casual conversations among friends.

During this time, he was invited to give a talk on Algonquin Park’s wildlife to researchers at the nearby Leslie M. Frost Natural Resources Centre, part of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. After the talk, a professor from the University of Waterloo approached Pittaway and asked him where he had earned his master’s degree.

“I said, ‘Master’s? I only have a technical diploma from Algonquin College!’” Pittaway recalled. “Before I left that day, they said, if you ever wanted to go to university and complete a degree, we’d give you credit for the technical work you’ve done.”

Pittaway enrolled in the University of Waterloo in 1977 and graduated two years later. In 1981, Pittaway left Algonquin to work at the Frost Centre full time. He stayed for 23 years, teaching Ontario high school, college, and university students about conservation science. The experience also introduced him to more naturalists and other bird experts who would later become part of his finch network.

In the 1970s and early ’80s, the number of field ornithologists in Ontario was growing, but they lacked an organization to unite them. That changed in 1982, when dozens of birders met at a high school outside of Toronto for the first meeting of the Ontario Field Ornithologists. Pittaway became one of the founding members of the organization. In 2005, the Ontario Field Ornithologists honored Pittaway with its Distinguished Ornithologist Award for his decades of contributions to the organization, including serving as an editor of the Ontario Birds journal and studying the Loggerhead Shrike to support its recovery in the province.

But it was Pittaway’s experience with winter finches that gained him notoriety in the birding world. In the 1990s, a writer for the Globe and Mail newspaper, Peter Whelan, would call Pittaway and other bird experts across Canada for information for his Saturday column.

“One year, I said, ‘It’s gonna be a super year for finches,’” Pittaway recalled. “[Whelan] said he wanted to run it, but was afraid of getting burned. A year or two later he started to see that it was happening, and he became confident in what I was saying and started including some of my predictions into his column.”

Not long afterward in 1999, Pittaway self-published his first official Winter Finch Forecast, posting his predictions in an email to the Ontbirds and Birdchat listservs.

“How meager it was compared to the ones we have now,” he said.

In its early days, Pittaway’s list of contributors was small and the forecast focused on Algonquin Park and the surrounding region in Ontario. But birders in the northern U.S. who read the Ontbirds listerv soon discovered his winter-finch forecasts served well south of the border, too. Pittaway began to get emails from U.S. birders asking him if they could reprint the predictions in their club newsletter or forward it to their own local listserv. It was copied all over the place, Pittaway said, from New York to Ohio.

“Pittaway’s forecasts had a tremendous impact on me,” says Matt Young, the Cornell Lab scientist who was inspired to build his own career around studying Red Crossbills. Today Young manages audio collections in the Macaulay Library and is one of the foremost experts on the different types of call vocalizations among the various subspecies of Red Crossbills.

“Ron’s predictions helped me dial in my search for crossbills when I first started studying them in the Northeast 20 years ago,” Young says.

“I couldn’t believe how popular it was,” Pittaway said of those early forecasts. “There is something about the boreal finches that excites the birder, something about their unpredictable nomadic nature.”

Because online communication was still an evolving technology, Pittaway’s long emails would often get reformatted and broken up as they were forwarded from place to place to place, until they were almost illegible. So, Pittaway and his partner Jean Iron concluded it would be best to post the entire forecast to Iron’s website and email out a link.

Over the next few years, Pittaway’s online Winter Finch Forecast gained a loyal following from birders hungry to hear what the coming winter had in store.

“People would ask me for the prediction before I released it,” Pittaway recalled. “It was all over the world, especially in irruption years.”

Pine Grosbeak by Joshua Galicki.

A White-winged Crossbill gathers seeds with its specially shaped bill. Photo by Marie Read.

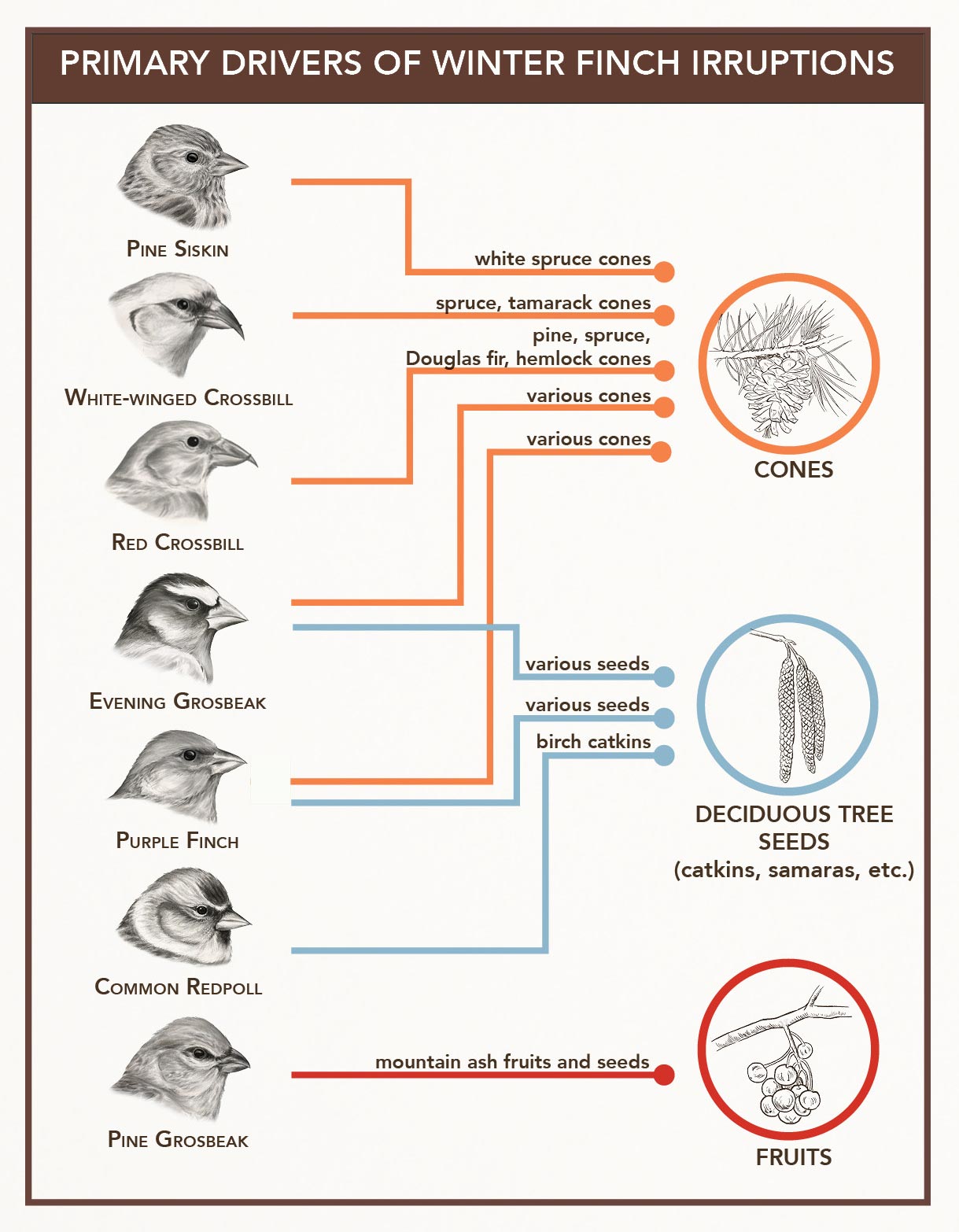

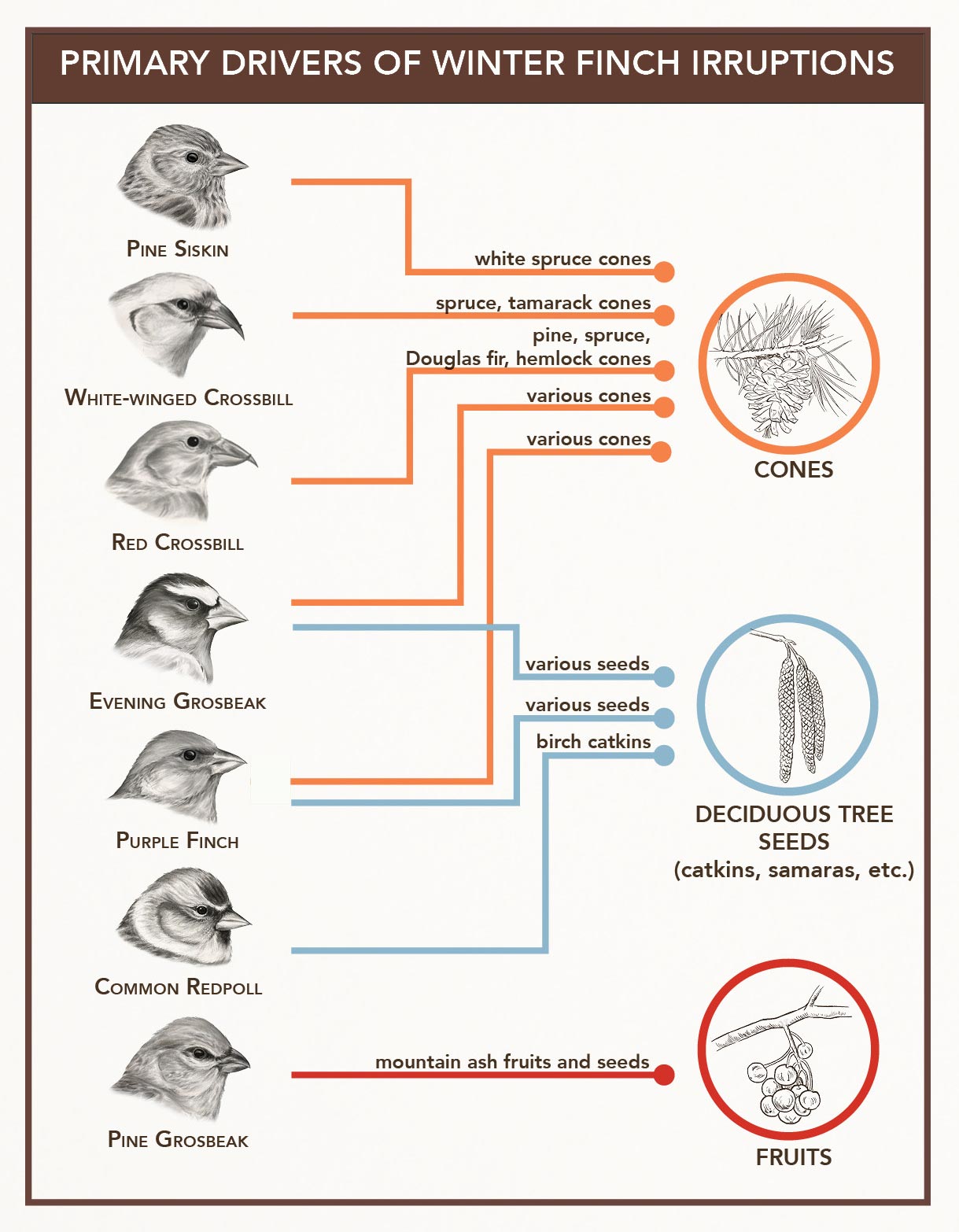

According to the Handbook of Bird Biology, an irruption occurs when large numbers of birds take flight and move beyond their typical range, usually in response to food supplies. The irregular, nomadic displacement of the boreal winter finches from year to year is closely tied to the summer production of seeds by trees.

Pittaway claims his forecast is an art rooted in science.

“When the conifer trees are bumper [crops] and the cones open, the birds just need to reach into them and pull the seeds out. There’s food everywhere,” said Pittaway. “When there is so much food of a bunch of varieties, the birds stay north.”

But if there’s a drought, or a frost in June, or other disruption that interferes with seed production, the seed crops fall below normal, and thousands of finches burst from the boreal forest and move south into the U.S. to search for food.

“My forecasts try to make sense of what might happen based on tree seed crops and knowledge of past irruptions,” said Pittaway. “Last year [a big irruption year] was easy, because there was no food. This year [a non-irruption year] was easy, because there was a superabundance of food. But there are lots of years that are in between. Those are the hardest years to predict.”

Different tree species produce bumper crops at varying frequencies. Eastern white pine, for example, will produce a bumper crop every three to five years, but rarely churn out two good years in a row. Eastern hemlock, on the other hand, will furnish a good crop every couple of years. The quality of the crop—good or bad—tends to be stretched out over hundreds or even thousands of miles of forest, forcing the birds to travel long distances to keep pace with the boom–bust cycle of food.

Pittaway’s forecasts are pretty simple in theory—a matter of knowing which crops are heavy in which places, and knowing which of those crops are prized by which finch species. The hard part is actually gathering and collating all that information from remote places in Canada. But over the years Pittaway has built up his connections with bird and tree experts who live in or travel to remote areas and feed him information. One contributor cuts a transect annually from southern Ontario to the edge of Hudson Bay, where she volunteers on a shorebird and goose study. She observes cone crops and other masting species while she travels north by car, train, and helicopter, and relays her observations to Pittaway back in Toronto.

Pittaway begins building his winter finch predictions in late summer, in his basement home office, which looks out over a wooded ravine. Over the years, he has amassed more than 30 trusted contacts—birders, government scientists, and other naturalists—spread across North America. In mid-August, he sends out a simple email asking each person to rate the seed crops for white spruce, black spruce, balsam fir, eastern hemlock, tamarack, white birch, yellow birch, alder, red oak, bur oak, mountain ash, and other food-bearing plants for birds, including hazelnuts, crabapples, and wild berries. Are they poor, fair, good, excellent, or bumper? He also asks, “Are you seeing finches?”

More on Winter Finches

The reports soon follow, pouring in from as far away as Alaska and Newfoundland, throughout Ontario and into Vermont, New Hampshire, and New York. Then to confirm reports or look in other areas, Pittaway does a little online surveillance, sometimes looking at photos people post to eBird, Facebook, and listservs to spy on trees in the background and look at the status of their masting.

Unusual weather for prolonged periods in the north helps shape the finches’ winter movements. Take 2012, for example. During the summer, much of North America found itself deep in a persistent drought. Corn crops withered and fruit wilted on trees as record-setting temperatures settled over much of the United States and Canada. By midsummer, the National Climatic Data Center was calling it the “largest moderate to extreme drought area since the 1950s.”

That year, as tree seed reports from Pittaway’s intelligence agents across the continent poured in, it became clear that a widespread crop failure was underway in the boreal forest, from northeastern Ontario through the Maritimes and into New York and New England. In September 2012, Pittaway wrote in that year’s forecast that “each finch species will use a different strategy to deal with the widespread tree seed crop failure.” He reported on the early signs of a Red Crossbill irruption and predicted a “good flight” of Pine Grosbeaks and “major southward irruptions” for Pine Siskins. Later that fall, a superflight of crossbills, redpolls, and grosbeaks flushed south. Minnesota’s Hawk Ridge recorded one of its largest Red Crossbill movements. In Pennsylvania, birders reported seeing clouds of Pine Siskins quivering over sunflower fields.

“The mystery behind winter finch irruptions is that we only see the seed crops in our area, but what determines the outcome is based on the collective,” says Marcel Gahbauer, a wildlife biologist with the Canadian Wildlife Service in Ottawa, who has been contributing tree seed information to Pittaway’s forecast for the past 12 years. For example, Gahbauer says, a good cone crop on white cedar in the Ottawa area might lead one to believe that winter finches would flock there. But if the crop is also healthy farther north in Ontario’s forests, the finches won’t come south.

“Even though there is a great crop here, there is no need for the birds to come to Ottawa, so it will remain largely uneaten,” Gahbauer says. That’s the genius of Pittaway’s forecasts, he says; they assemble all the pieces of a puzzle stretching across the boreal forest.

But Pittaway doesn’t use any sophisticated software, spreadsheets, or even a dry-erase mapping board. As his contacts reply to his email, Pittaway mulls over the reports: He weighs the seed crop abundance of one tree species against another, pinpoints their locations, compares them to previous years, and looks for backup food sources—such as berries or outbreaks of spruce budworms—that might allow the birds to stay put. As patterns begin to surface across Canada, Pittaway begins to anticipate what he might hear from other contacts farther to the east or north.

Over two or three weeks, the pieces fall into place until Pittaway has built a seed crop map of North America in his mind. He produces a first draft of the Winter Finch Forecast by late August, and updates it as more information rolls in, until he has heard from most contacts.

Usually by the third week of September, Pittaway and Iron post the forecast online. In September 2018, social media lit up with Pittaway’s forecast for a winter-finch irruption, in which he wrote: “Stock your bird feeders because many birds will have a difficult time finding natural foods this winter.”

“Holy cow people, this winter has PINE GROSBEAKS written all over it,” read one Tweet.

“‘On the edge of my seat’ would be an understatement. BRING IT! #birdnerd,” read another.

Sure enough, eBird maps show that Pine Grosbeaks swept south into New England and northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota during the winter of 2018–19. Pine Siskins flooded across the U.S. as far as Arizona, Texas, and Florida. There were reports of Evening Grosbeaks—the supersized flaming dandelions of winter finches—in downtown New York City. Reports of Purple Finches at backyard bird feeders blanketed the eastern U.S.

“I was confident, based on past experience, that we’d have a flight of purple finches,” Pittaway said as he sipped coffee in his dining room recently and reflected on last year’s irruption. Outside his window, a puffy Downy Woodpecker tottered on a branch. “You’d be hard-pressed to find a Purple Finch in Ontario right now.”

This winter is a different story. Pittaway’s 2019–2020 Winter Finch Forecast began with this sentence: “This is not an irruption (flight) year for winter finches in the East.” Abundant cone and seed crops across Canada will keep winter finches locked in the North, he predicted.

A collective sigh rippled across social media.

“Not good news for us in NYC,” tweeted one birder.

“You can’t take [winter] finches for granted, because you don’t know if they’re going to be around the next year,” says Gahbauer, the Canadian Wildlife Service bird specialist.

Pittaway said he understands the excitement, and disappointment, elicited by his forecasts.

“There’s something magical about winter finches, something mysterious about where they come from,” Pittaway said. “The fact that someone can tell [birders] that there are going to be some finches down in their neighborhood, I think they’re just mesmerized by that.”

As for the future, Pittaway hazards a guess that next year will be a better one for backyard birders who like to see winter finches, based on the fact that back-to-back bumper cone crops in the boreal forest are rare.

“It’s likely tree seed crops will be much lower next year,” Pittaway said, “and southern birders can expect some finches to irrupt.”

Hannah Hoag is a science and environmental journalist based in Toronto, where she is a deputy editor of The Conversation Canada. She has written for numerous publications including bioGraphic, Audubon, The New York Times, and The Atlantic.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you