Seven Sublime Birds From Around the World

By Marc Devokaitis

January 9, 2020From the Winter 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now. Content adapted from Birds of the World.

Birds were making a living on Earth more than 100 million years ago—that makes them 20 times older than the earliest upright-walking apes, and 400 times older than the earliest known Homo sapiens, modern humankind’s species. As two-legged, world-spanning, warm-blooded vertebrates that are mostly active by day (all traits they share with humans), birds’ long-term tenancy on Earth gives us food for thought: Why have birds been successful? What can they teach us?

Answering these questions is at the heart of the scientific study of birds. And because the more than 10,000 bird species around the world are a riot of colorful, complex, and occasionally kooky creatures that are relatively easy to observe, the body of scientific research on birds is immense. A Google search for the word “avian” in scholarly articles returns nearly 1.5 million results.

When Lynx Edicions published the Handbook of the Birds of the World in 2011, it was an ornithological landmark. After many millennia, the world finally had its first comprehensive scientific review of the Aves class in the animal kingdom, with 17 print volumes of species accounts and illustrations for every bird on the planet.

In early 2020, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology will release the next generation of this dynamic resource: Birds of the World. This expanded online version will be a living, scholarly publication that is regularly updated by global experts and enhanced by photos, videos, and audio recordings from the Cornell Lab’s Macaulay Library. It will also include data and analyses from the global community of eBird.

Hidden within the 10,721 species accounts of the new Birds of the World are some avian gems of planet Earth—a burrowing shorebird in the Middle East, a poisonous oriole in Southeast Asia, a South American waterbird with a spiny appendage atop its head. Every bird is amazing in its own way, but some stand out by virtue of beauty, exquisite adaptation, or flair for the bizarre.

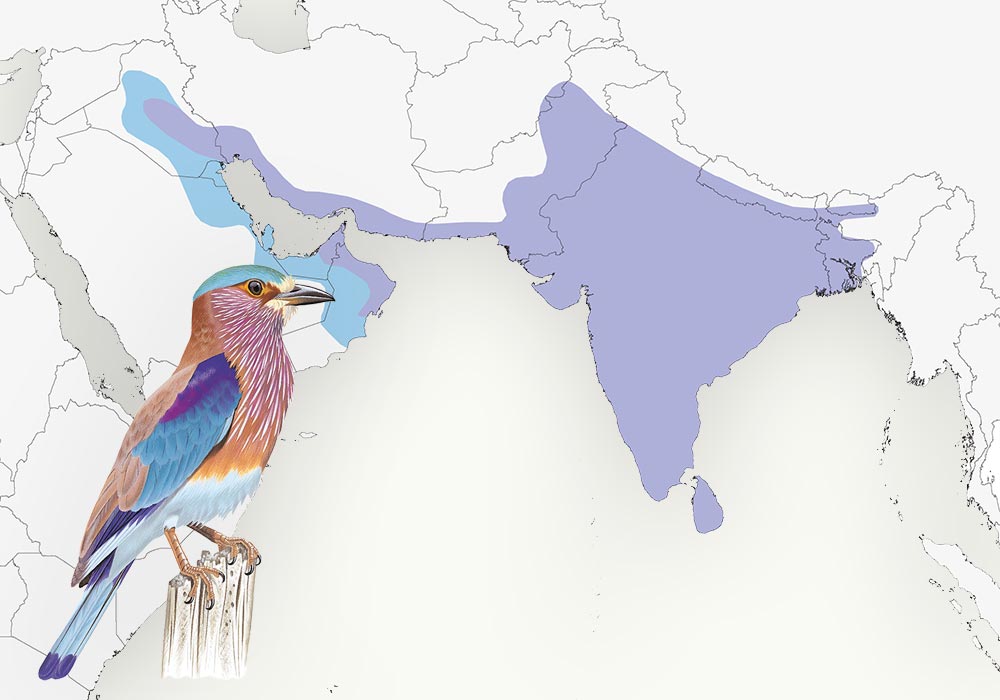

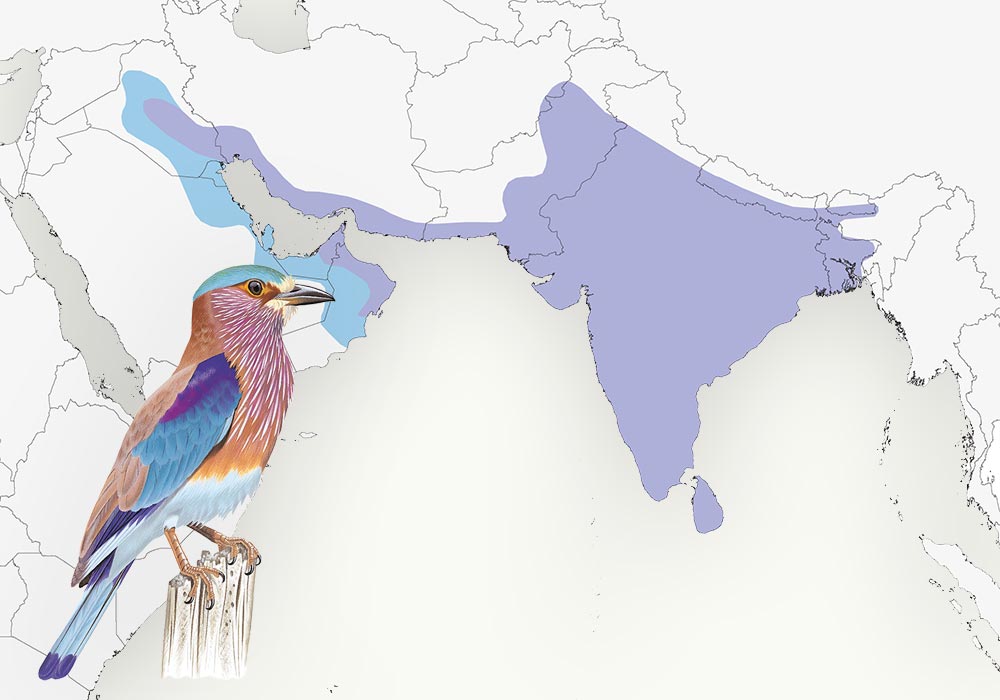

Indian Roller: Acrobat of the Indian Plains

In Sri Lanka, the Indian Roller (Coracias benghalensis) is colorfully known as “the one who inhales smoke” for its habit of hunting around bush fires. While the species occurs from Southeast Asia to the Arabian Peninsula, Indian Rollers are most common in the heavily populated plains of India, and as such figure prominently in local lore. One local name for the species is neelakant meaning “blue throat,” a name associated with the Indian deity Shiva, whose blue throat resulted from drinking poison. Other common colloquialisms are “blue crow” or “blue jay,” perhaps because rollers display several corvid-like attributes such as being noisy, comfortable around humans, and omnivorous.

Male rollers perform acrobatic aerial rolls during their courtship displays, and sometimes as a defensive tactic around their nests. These defensive flights are sometimes directed at nearby humans, but despite this occasional aggression, Indian Rollers are widely tolerated by people and welcomed as garden birds.

White-necked Rockfowl: The Perplexing Picathartes

Rockfowl (Picathartes species) are bizarre, beautiful songbirds that are hard to mistake for any other bird. They look like a cross between a gamebird and a crow, but the two rockfowl species—White-necked and Gray-necked—are the only members of their own family, Picathartidae, and not closely related to any other bird groups.

Rockfowl haunt rocky, hilly forests in parts of West Africa, where they build mud nests on rocky outcroppings. (Read this article on White-necked Rockfowl from our Summer 2013 issue.) When foraging, they move through the understory with slow, bounding hops, investigating the leaf litter for insects and occasionally following columns of army ants. While the White-necked Rockfowl can adapt to living in fragmented forests and is sometimes found close to humans, it is a species rated as vulnerable to extinction by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. There are fewer than 10,000 White-necked Rockfowl left in the world. Loss of forest habitat is considered the biggest threat to the species.

Spotted Pardalote: Jewel of the Eucalyptus Trees

Also known as peep-wrens, the pardalotes are one of many families of songbirds endemic to Australia. These kinglet-sized insectivores forage mostly in the canopies of eucalyptus trees. There are four species in the family, including the double-named Spotted Pardalote (Pardalotos is a Greek word meaning “spotted like a leopard”).

During breeding season Spotted Pardalotes (Pardalotus punctatus) may nest in urban and suburban areas. They typically build their nests inside horizontal tunnels that they dig into a roadside berm or an eroded streambank. But occasionally these jewel-like birds thrill Australian backyard birders by setting up in nest boxes, tree cavities, or roof eaves.

Hooded Pitohui: That Bird is Poison

The Hooded Pitohui (Pitohui dichrous) was the world’s first documented poisonous bird. A researcher with the Smithsonian Institution made the accidental discovery in the forests of New Guinea after being scratched by a Hooded Pitohui that he was removing from a mist net. After his hand began to go numb, he licked the cut and found his mouth starting to tingle as well.

Researchers eventually determined that the pitohui’s toxicity comes from a beetle that it eats. Along with its baneful constitution, this bird’s bright colors and strong, sour odor serve to ward off predators.

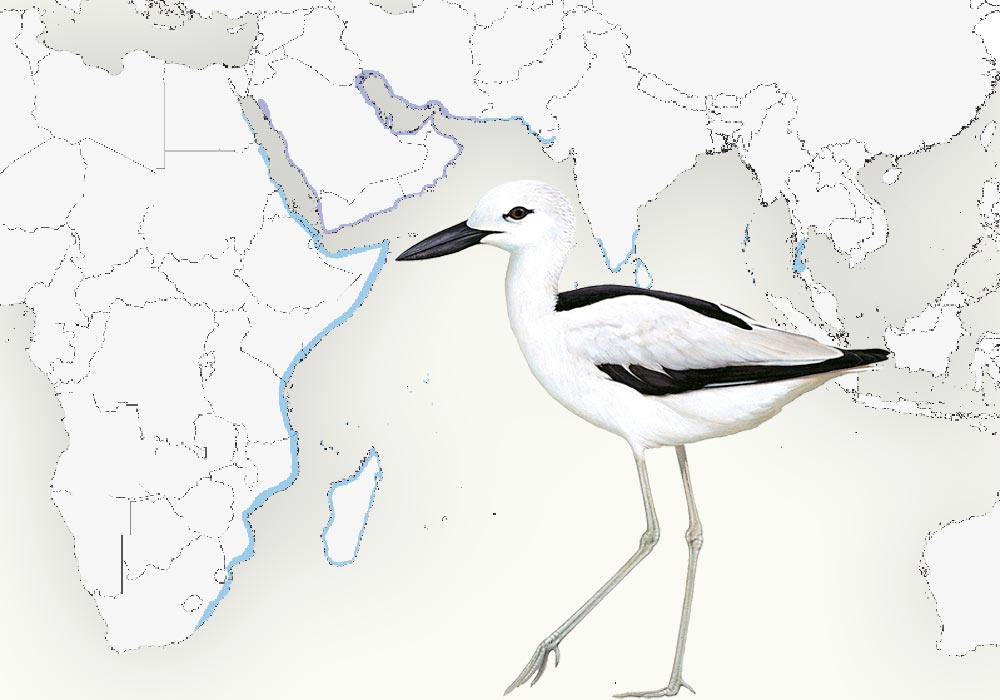

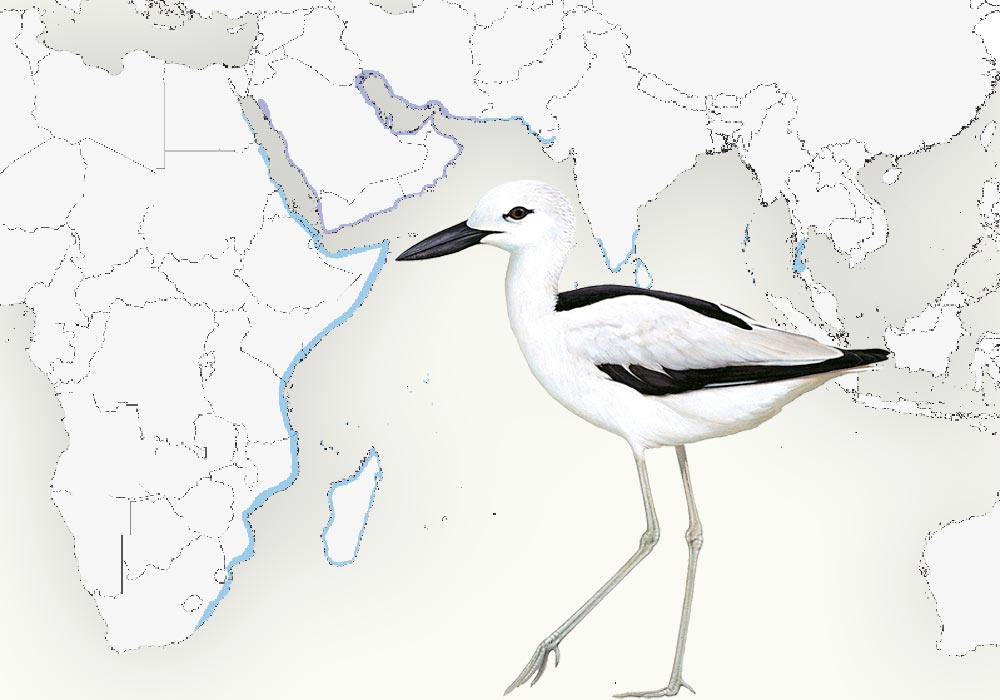

Crab-Plover: The Shorebird That Burrows

The slightly down-curving gape at the base of the Crab-Plover’s (Dromas ardeola) hefty bill give this unique wader a slightly sad expression. Happily, the global population of this species, which lives on beaches from East Africa to Southeast Asia, is stable and healthy. The Crab-Plover uses its daggerlike beak to stab and break open a variety of small-and medium-sized crab shells.

The Crab-Plover’s unique nesting behavior sets it apart from all other shorebirds, such as sandpipers. Crab-Plovers excavate burrows in coastal dunes. This strategy may hide the nest from predators, as well as provide protection from the intense solar radiation the chicks would otherwise experience on a sunny, sandy beach. As it happens, the Crab-Plover’s burrows tend to maintain an ideal temperature for incubation, so the parents often get some free time away from sitting on the eggs. A study found that Crab-Plover eggs in one population were attended for less than 30% of the time before hatching, with some adults staying off the nests for more than two days.

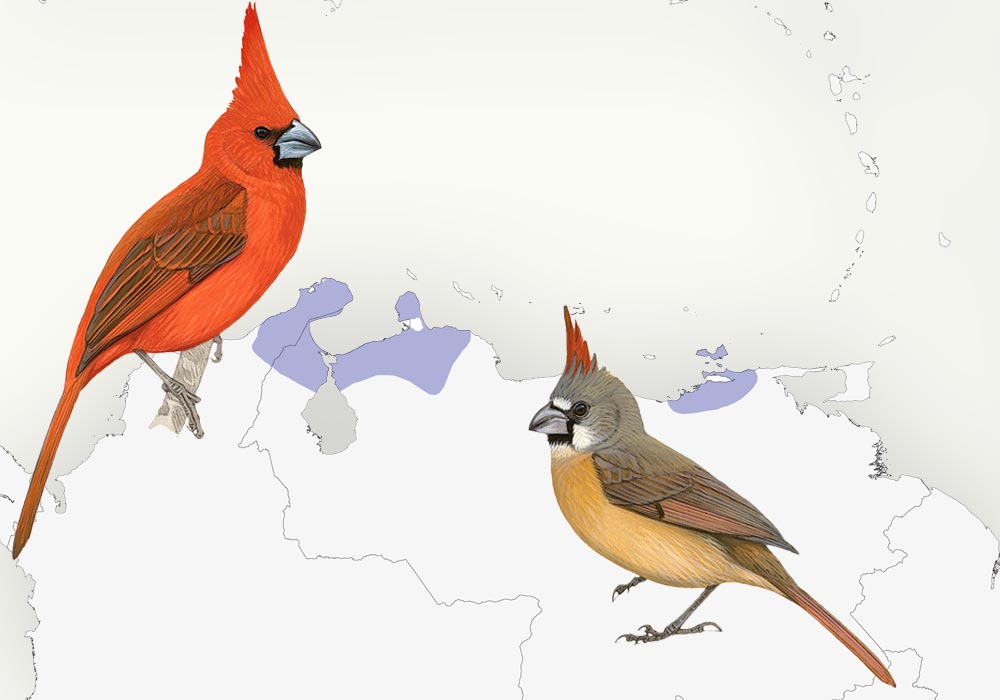

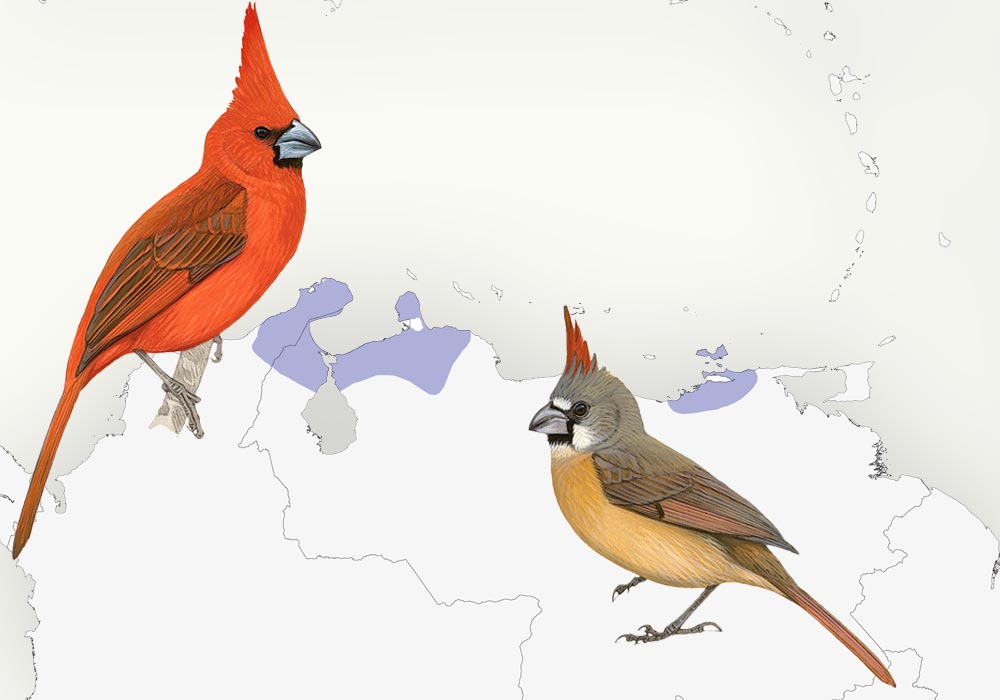

Vermilion Cardinal: Punk Rocker, Glowing Red

Think of the Vermilion Cardinal (Cardinalis phoeniceus) as the “Southern Cardinal”—it’s the most southerly member of the Cardinalis genus, which includes just two other species: the Northern Cardinal and the Pyrrhuloxia from North America. The glowing rose-red hues of the male Vermilion Cardinal outshine even the holiday-card scarlet of the Northern Cardinal. As if that were not enough to garner attention, the Vermilion Cardinal also has an elongated spikelike crest that is almost always held straight up.

Vermilion Cardinals live among the desert scrub and dense thickets along the Caribbean coasts of Venezuela and Colombia. Despite the small range of the species, these birds can be quite common in their preferred habitat. Birders look for Vermilion Cardinals in the cool of the early morning, when males perch conspicuously and announce themselves with clear, loud whistles strikingly similar to the cheery song of the Northern Cardinal.

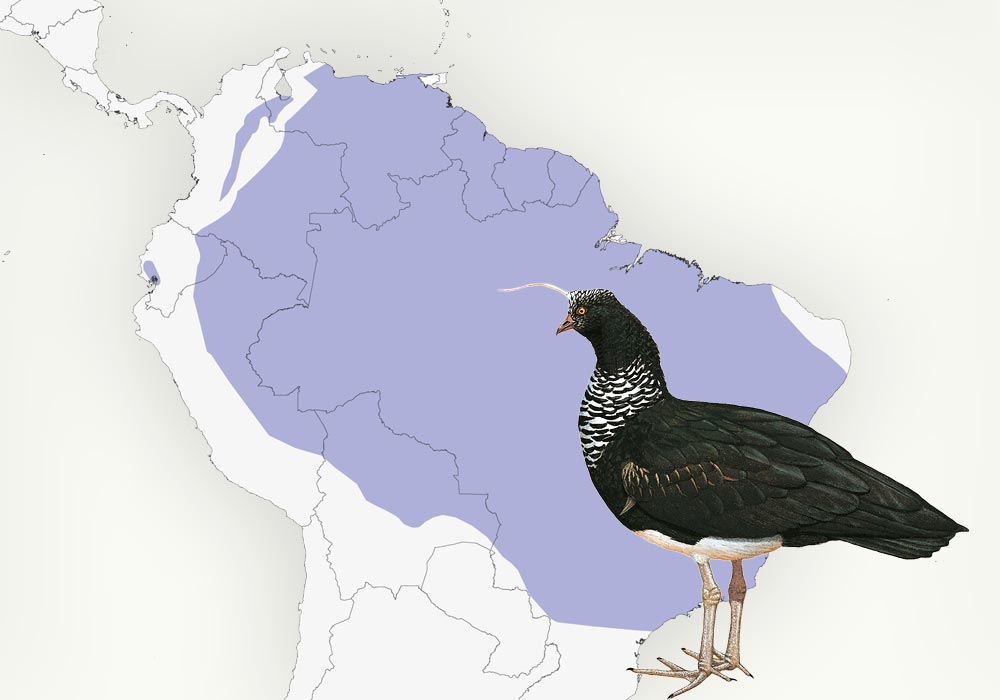

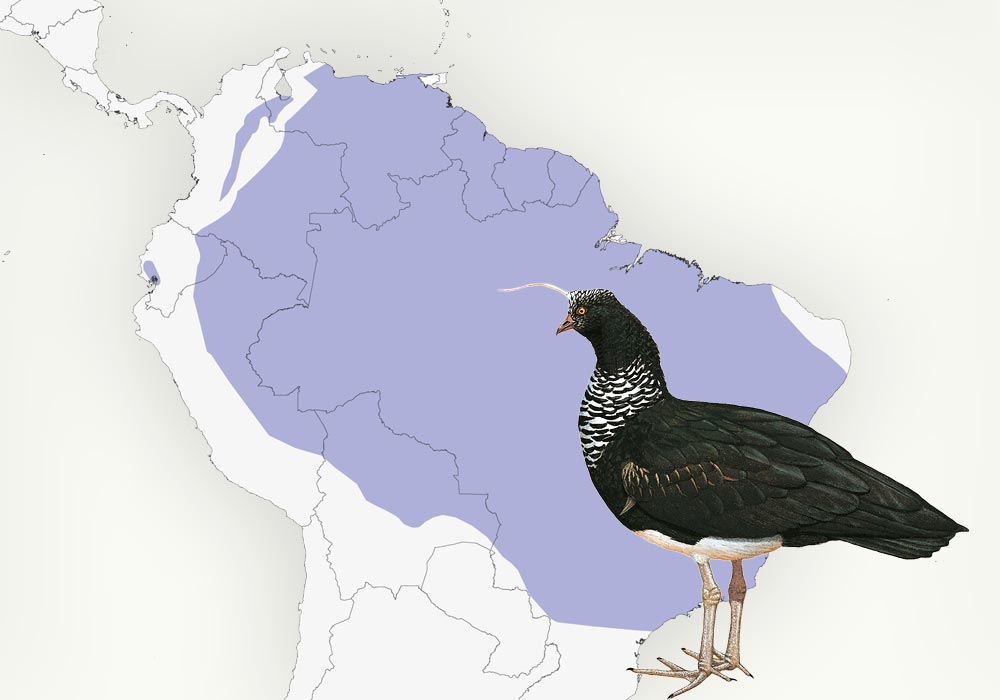

Horned Screamer: Unicorns Do Exist

Screamers are living specimens from the ancient past. They share a lineage with present-day geese, ducks, and swans, but they look more like misshapen gamebirds than waterbirds, thanks to their small chickenlike head and sharp, curved bill.

The enormous, ungainly Horned Screamer (Anhima cornuta) lives on open plains and wetlands throughout much of the Amazon Basin and eastern Brazil. Its horn is a long, thin piece of cartilage growing out of its forehead. Like the other screamer species, Horned Screamers also sport two extremely sharp, long, curved spurs that protrude menacingly from the bend of each wing. While the spurs are used in territorial fighting, the horn is probably used mostly in sexual signaling, as it is very brittle and prone to break off. (When it does, it grows back.)

As its name implies, the Horned Screamer’s voice is very loud and distinctive—a deep, reedy HA-MOO-CO often uttered in chorus with others of its kind. They can also make a distinctive cracking sound by collapsing a complicated system of air sacs just under their skin.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you