Analysis: Is It Possible to Have Wind Power While Keeping Birds Safe?

By Gustave Axelson

March 31, 2020From the Spring 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

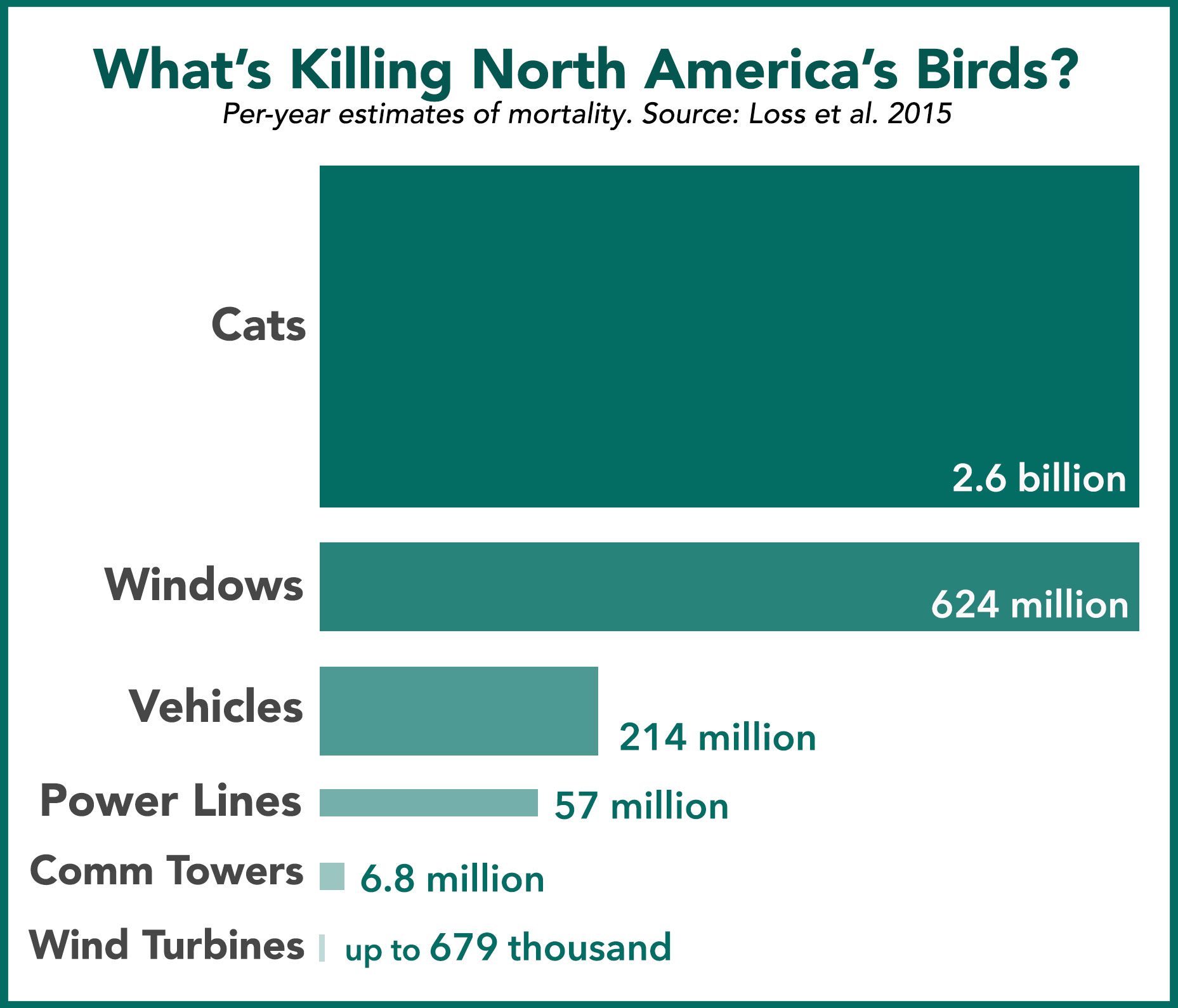

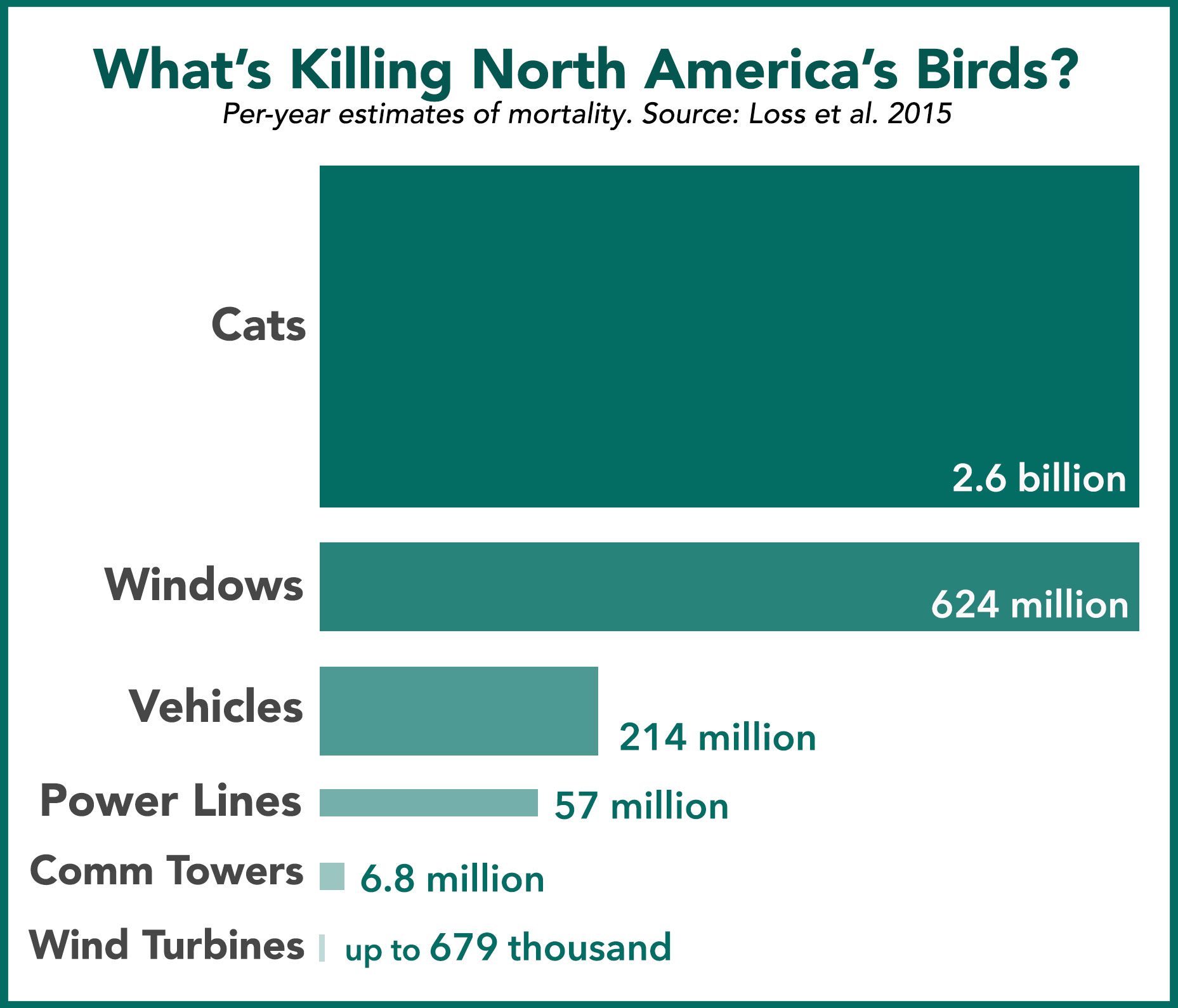

Wind turbines are not a major source of overall bird mortality, but they do kill birds in some areas.

According to research published in the journal Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics in 2015, an estimated 234,000 birds are killed annually in the U.S. from wind turbines. That’s well below other causes of direct bird mortality, including communication towers (6.6 million birds killed), building collisions (599 million), and cats (2.4 billion).

Yet there have definitely been some troubling instances of kills of some kinds of birds, especially raptors, at wind farms that were placed near bird breeding areas or migration corridors.

The Altamont Pass in northern California was home to one of the first big wind farms in the United States in the early 1980s, and unfortunately it was located, or sited, in an area frequented by hawks and Golden Eagles. At one time, more than 7,000 wind turbines were spinning along the mountain ridges at Altamont, and an estimated 1,300 raptors were killed per year there. In 2010, several local Audubon groups, along with the California attorney general, reached a settlement with wind-power operators to mitigate the bird kills at Altamont. The agreement aimed to reduce deaths of Golden Eagles, Red-tailed Hawks, Burrowing Owls, and bats by half. Since then, hundreds of wind turbines at Altamont have been powered down, and others have been replaced with next-generation turbines designed to be less lethal to raptors.

Read the Full Story

Yet the problems at Altamont still aren’t solved, says Pam Young, executive director of Golden Gate Audubon Society in Berkeley, California. Golden Gate Audubon is continuing to press for more bird-friendly measures at Altamont. Young says monitoring at just one site in the Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area documented kills of 32 Golden Eagles and 111 Red-tailed Hawks, and estimated kills of 49 Burrowing Owls and 1,742 bats over a recent three-year period. In a letter to the local county zoning board in February, Young wrote that bird mortalities still appear to be above the levels set in the mitigation agreement.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology scientist Orin Robinson worked with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Raptor Program to develop a wind-energy model that may help avoid future conflicts like the controversies that have plagued Altamont. Using eBird Status and Trends models, the team built a map that identifies low-risk areas where wind turbines pose the least danger to Bald and Golden Eagles—two species with special federal protections under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. USFWS is in the process of adopting the model to guide federal approvals for wind turbines.

According to the head of conservation science at the Cornell Lab, wind energy in general can be a good thing for birds, if it’s done right.

“We need to be mindful that generating energy in any manner will impact birds directly or indirectly. Bird mortality from wind turbines may be more obvious than from other sources, but the habitat loss, water contamination, pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions from other energy sources, especially coal, are far more detrimental to birds and other species, including humans,” says Amanda Rodewald, codirector of the Cornell Lab’s Center for Avian Population Studies. “Fortunately, the conservation community has a real opportunity to reduce negative impacts from wind energy by working with industry to properly site turbines and avoid important bird areas.”

That’s a position shared by many other bird groups. Joel Merriman, director of the Bird-Smart Wind Energy Campaign at the American Bird Conservancy, says, “Wind energy and birds can coexist, but only if turbines are sited and managed properly. Alternative energy is critically important to address climate change, but we strongly believe that renewable energy sources should not be embraced without question. It must be demonstrated that the benefits outweigh the impacts.”

ABC developed its own wind-risk assessment map to highlight areas important to birds, and the group has been involved in recent legal battles over what it considered to be poorly sited wind projects—including a lawsuit against the federal government on a proposed offshore wind project in Lake Erie near Cleveland that sits along a major bird migration corridor and wintering area.

Audubon also stresses the need for bird-friendly wind energy on its website, stating that the group “strongly supports properly sited wind power as a renewable energy source that helps reduce the threats posed to birds and people by climate change.” Last year, Audubon released a report estimating two-thirds of North American birds are at increasing risk of extinction from rising temperatures.

So while wind in the wrong places is definitely bad for birds, the Cornell Lab, American Bird Conservancy, and Audubon all agree that wind in the right places can help make the planet a better place for birds. Pam Young, the Golden Gate Audubon chapter executive director who’s fighting the Altamont wind farms, agrees on that point, too.

“More energy from wind, less from fossil fuels, is good news for birds,” Young says.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you