Power or Prairie: Can Wind Energy and Wildlife Coexist in the Flint Hills?

Story by Greg Breining; photography by Jonathan Fiely

Elk River wind farm near the Flint Hills, Kansas. April 3, 2020From the Spring 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

The photography for this story was made possible with support from the Robert F. Schumann Foundation, a charitable trust dedicated to improving the quality of life of both humans and animals by supporting environmental, educational, arts, and cultural organizations and agencies.

Kansas rancher Brian Obermeyer was driving across Iowa in 2001 when he spotted a wind farm for the very first time, the gleaming alabaster pillars shooting upward and graceful blades carving arcs in the sky.

“My first reaction was, ‘Cool, a wind farm!’” he recalls. Obermeyer had just started working for The Nature Conservancy, and he was headed to a meeting in Minneapolis. Then he had a startling thought—what if a wind farm like that sprouted up on the wind-blown prairie plains in eastern Kansas?

“It wasn’t just a few months later we found out about all these prospectors out here working the Flint Hills, leasing up land for wind farms,” he says.

Obermeyer, now director of land protection and stewardship for the Conservancy in Kansas, tells the story as he drives his truck along a gravel road snaking over the rolling hills of the Tallgrass National Prairie Preserve. The Flint Hills landscape is spectacular. Grasses blanket the hills to the horizon.

The Flint Hills, with 90 species of grasses and 600 wildflowers, is the largest unbroken remnant of the tallgrass prairie—an ecosystem dominated by big bluestem, Indiangrass, and switchgrass that can tower over the head of a person walking through them. Tallgrass once covered the midcontinent, approximately 170 million acres from Texas to Canada. Today bison graze on a section of the Tallgrass National Prairie Preserve in Kansas. In days gone by, we might have seen pronghorns, elk, wolves, and perhaps even a grizzly.

“Tallgrass prairie—it’s a pretty sad story when you think about it,” says Obermeyer. “Much of it was prime farmland that was just aching to be plowed by settlers. Historically Iowa had more tallgrass prairie than Kansas did.”

But today, “most of the tallgrass prairie in Iowa is growing corn and soybeans,” he says.

Only about 4% of tallgrass prairie remains, and two-thirds of that lies in the Flint Hills of eastern Kansas and Oklahoma (where the same formation is called the Osage Hills). The Flint Hills was saved by its thin, cherty soil. Nearly impossible to plow except in the fertile bottomlands, it was given to grazing, which perpetuated the native grass.

Obermeyer stops his truck atop a hill, affording a clear view of the far horizon in all directions: “From this vantage point here, there’s more tallgrass prairie within a 20-mile radius than all the other prairie states and provinces combined, not counting Oklahoma,” he says.

We jump from the truck and shift our gaze to the various species of grasses and forbs at our feet.

Greater Prairie-Chicken in the tallgrass. Photo by Jonathan Fiely.

The Elk River Wind Project near Beaumont, Kansas, was built right at the southern edge of the Flint Hills, home to the largest remnant of tallgrass prairie. Photo by Jonathan Fiely.

The rock-strewn rolling hills of the tallgrass prairie in the Flint Hills made most of the area inhospitable to crop agriculture, but perfect for grazing animals. Photo by Jonathan Fiely.

The Flint Hills tallgrass prairie is prime grazing grounds for bison. Photo by Jonathan Fiely.

“It’s a place where you can kind of hear yourself think,” Obermeyer continues. “You’ve got a clean horizon.”

But increasingly, wind turbines are popping up on horizons around the Flint Hills. While it isn’t the windiest spot in Kansas, it’s windy enough—and near enough to big markets such as Kansas City—to attract wind-energy developers. And wind power is booming in Kansas: The installed wind-generation capacity in the state has jumped 500% in the last decade.

That creates a dilemma for conservationists such as Obermeyer, who favor renewable energy to fight climate change but also treasure unbroken expanses of vanishing ecosystems such as the tallgrass prairie.

How to accommodate two competing views of what it means to conserve nature? Obermeyer and his colleagues at The Nature Conservancy have a plan.

A Haven for Grassland Birds and Shorebirds

As a large grassland, the Flint Hills are vital to ground-nesting birds such as meadowlarks, Henslow’s Sparrows, Grasshopper Sparrows, and Dickcissels. Prairie lakes and ephemeral ponds known locally as playas also attract waterfowl and shorebirds by the tens of thousands. As a natural north-south corridor, the Flint Hills are an important migration route for shorebirds, such as American Golden-Plovers and Killdeer. Even though it’s well over a thousand miles from the nearest coast, the Flint Hills is designated as a Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network site. It supports more than 30% of the world’s Buff-breasted Sandpipers during their migration.

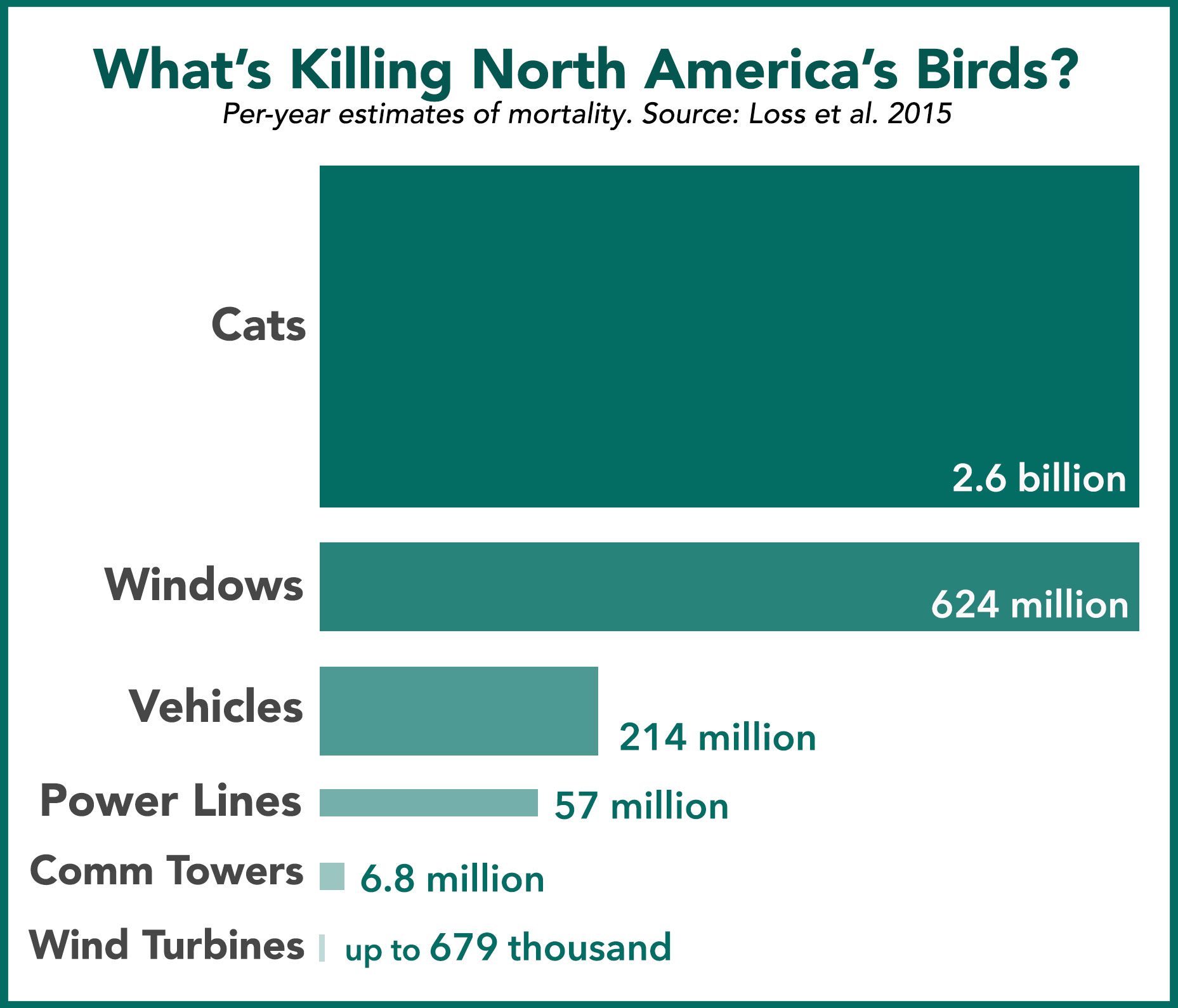

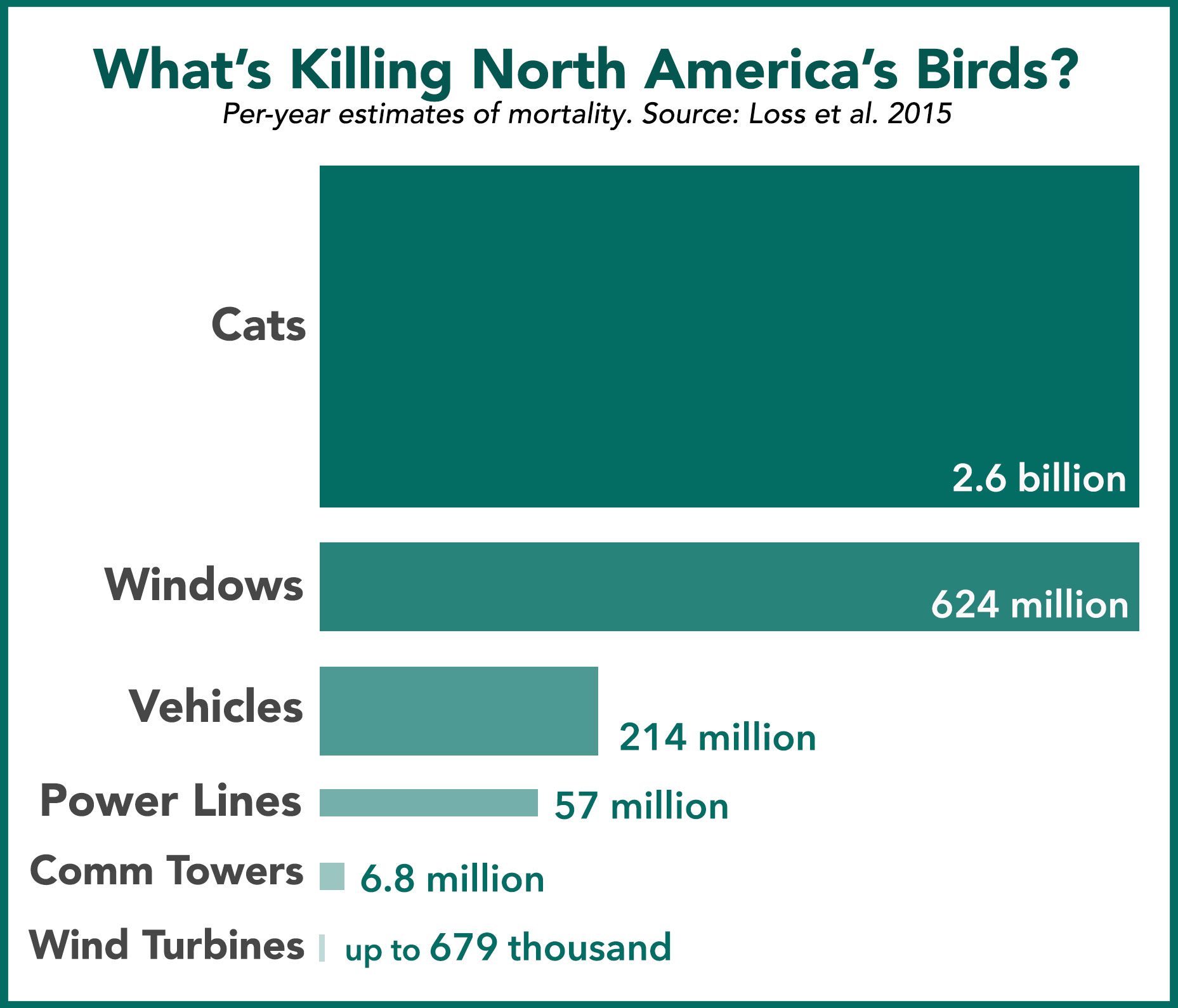

These are groups of birds that, by and large, are not doing well. According to research published in the journal Science last year, the grassland-breeding bird population across the U.S. and Canada has declined by more than 50% since 1970. Other research has depicted a migratory shorebird population that is down by more than 70% in that period.

The Elk River Wind Project was sited in the core of a key midcontinental region for bird habitat. Today wind turbines spin in the midst of a breeding area for grassland birds such as Eastern Meadowlarks. Photo by Matt Aeberhard.

American Golden-Plovers forage on farmland during a migration stopover on former prairie land. Photo by Matt Aeberhard.

If any bird is emblematic of the Flint Hills, it is the Greater Prairie-Chicken, regarded by local ranchers as a prized game bird and symbol of their big-sky homeland. During spring breeding season, male prairie-chickens gather on display grounds called leks, where they raise plumes on their heads and inflate bright orange air sacs on their necks while drumming their feet, whooping, and cackling to impress the onlooking hens.

Greater Prairie-Chickens once ranged across the grasslands of the eastern United States to the Front Range of the Rockies, but like the tallgrass itself, that range has shrunk to a sliver. Now, these prairie-chickens live in Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas, with scattered populations in neighboring states.

The Flint Hills is a prairie-chicken stronghold. Short grass, high ground, and hilltops provide the perfect lekking sites. Taller, thicker grass on the low ground provides nesting cover to hide eggs and newly hatched chicks from soaring hawks and prowling coyotes.

Greater Prairie-Chickens “need a lot of different kinds of habitat,” says Virginia Winder, associate professor of biology at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas. “When one of those things is missing, that causes a problem.”

Once upon a time, the Flint Hills provided these things in abundance.

Back in the middle of the 20th century, Jim Hoy grew up on a ranch near Cassoday, Kansas, where a sign (now gone) posted along the road into town proclaimed it to be the “Prairie Chicken Capital of the World.” Hoy’s family grew a little corn for the cows and tied the stalks into shocks before harvest.

“I’d drive out in the morning with a team of mules pulling a wagon,” recalls Hoy, “and there’d be 40, 50, 60 [prairie-chickens] sitting on those shocks eating the grain. Dad did not begrudge them, because a couple times a winter he’d take the .22 with him and we’d have prairie-chicken for dinner.”

Steve Sundgren also grew up on a ranch near Cassoday. Back in the late 1940s, his family would regularly invite a few friends to their ranch for a big feed and prairie-chicken hunt. The hunters would hide in fencerows and shoot birds as they crossed from grassy roosting spots to foraging spots among small fields of soybeans and sorghum.

“Oh, my gosh, it was just unbelievable when I was younger,” Sundgren says. The skies were filled with prairie-chickens—“hundreds and hundreds of them.”

The hunting was so good, local politicians began stopping by the family ranch and the crowd soon grew to 60 or 70 shooters.

“People from all over the United States would come here to hunt,” recalls Sundgren. “One Sunday morning, we killed 197 prairie-chickens.”

Sundgren just completed his 60th hunt.

“We shot 11. My wife and I have been wanting to quit and our friends won’t let us. It’s camaraderie now, it’s not the hunt,” he says. “The population is really down, it’s gone down tremendously.”

“Chicken populations in the Flint Hills have been declining for many decades,” confirms Jeff Prendergast, small game specialist for the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism. Yet it’s not hunting or even wind development that has driven the decline. Rather, it’s the changing patterns of grazing and the use of fire.

Ranchers used to burn their grasslands every three or four years to promote new growth and revitalize the forage for livestock. But about 30 years ago ranchers began “intensive early stocking,” says Obermeyer—loading the prairie with twice the number of cattle for half the season. Then they began burning more aggressively, almost yearly. According to Obermeyer, private ranchers burned 2.8 million acres of the 4.5 million–acre tallgrass landscape in Kansas and Oklahoma last year. Cattle grazing and annual burning can create terrific prairie-chicken leks, but too much grazing and burning destroys the grassy nesting cover needed to shelter eggs and hatchlings.

Elsewhere in the prairie-chicken’s range in Kansas, fires have been scarce and trees are encroaching on the prairie from the edges. Whether it’s too much disturbance, or too little, the overall problem of habitat degradation has hurt the birds, Prendergast says.

And if mega-wind farms sprout up on what remains of good prairie-chicken habitat, the problem could get worse.

A New Threat

As wind power takes off in Kansas (last year, the state ranked fourth nationally in installed wind capacity), Obermeyer and others worry about the effect of the turbines on prairie-chickens.

Unfortunately, prairie-chickens and wind turbines like the same habitat—high, windswept areas without trees. And there’s evidence they don’t coexist well.

“Chickens don’t seem to like vertical structures, whether it’s trees or transmission lines,” Obermeyer says. He says trees and power lines provide lookouts for the hunting raptors that prey on prairie-chickens. As well, the “shadow flicker” from the wind turbine’s sweeping rotors may stress hens and make them more likely to abandon the nest. “It kind of mimics a bird flying over.”

Some research backs up Obermeyer’s concerns. Winder, the biology professor from Benedictine College, studied the before-and-after effects of the Meridian Way Wind Power Facility in north-central Kansas, just outside of the Flint Hills. She found prairie-chickens showed a tendency to abandon leks near turbines. After construction, male prairie-chickens were three times more likely to abandon leks within five miles of a turbine than leks farther away.

“The most drastic effect is right next to the turbine,” says Winder.

Yet she found no evidence that turbines negatively affect nest selection, nest survival, or adult survival.

“If you’re looking for me to tie this all up into a neat story, there isn’t one,” she says. “I can’t say that wind energy is always good or it’s always bad.”

Larkin Powell, professor of conservation biology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, was a coauthor on Winder’s paper and has also studied prairie-chickens on a wind farm in Nebraska’s Sandhills. He concurs that the threat of wind power isn’t clear cut.

Natural gas and oil development, with more noise and traffic, seem to drive out prairie-chickens more than wind does, he says. But, he adds, wind power with its growing footprint on the landscape could be a bigger potential problem in the future.

“I would always say there’s still potential if in the future wind facilities are bigger and there’s more infrastructure,” Powell says.

Drought Strikes Fear

For some ranchers, concern for prairie-chickens competes with the need to diversify their sources of income.

When a wind developer first approached fourth-generation Flint Hills rancher Pete Ferrell in 1994, “my answer was no,” he says. But after researching wind development and talking to ranchers in California who had leased land for wind towers, Ferrell changed his mind.

The Elk River wind facility was completed in 2005 south of Beaumont, Kansas, on ranches belonging to Ferrell and two neighbors. On a sunny afternoon, 100 turbines—each reaching more than 30 stories high—spin on either side of Ferrell Ranch Road. The rotors, 250 feet across, whisper in the light breeze. Nearly 18 miles of heavy-duty service roads wind among the turbines.

Ferrell explains his change of heart: “Drought strikes fear into the heart of every rancher. What happens if I have to de-stock? How do I keep up my financial commitments in the face of drought?”

During the drought of 2010–13, he cut his cattle herd by 40% and his ranch survived, while others across the Great Plains folded.

“So the wind farm gave me latitude to survive drought,” he says. “I always say it’s my best crop because the wind always blows, even during the drought.”

Ferrell says he was also motivated by the threat of climate change: “At the time the wind farm was built, no one seemed to take this seriously. Many still don’t.

“I knew I was going to change the view-shed in the Flint Hills, but I thought that it’s more important to save all the birds and to be considerate of all the ecosystems on the planet. We have to get carbon out of our energy mix as quickly as possible. I’m painfully aware of the climate crisis that we’re facing.”

As he leased his land for turbines, Ferrell says, he fretted about the prairie-chickens on his property, including several active leks. A consulting firm mapped leks and counted birds two years before construction began.

“I was really concerned about the welfare of the Greater Prairie-Chicken. We went into it armed with the best knowledge at the time. You know, I would have been devastated if we couldn’t prove that the Greater Prairie-Chicken was going to be okay.”

After construction, Ferrell says, he invested some of his wind-farm money to improve prairie-chicken habitat.

“I cut down every tree on eight sections of ground where the wind farm was to make sure there was no perch for Red-tailed Hawks,” he says. “The second thing I did was I completely mitigated our burn policy so we were sure not to burn their house down every year.”

After construction, the number of prairie-chicken leks within a mile of the wind project plummeted, according to a survey commissioned by the developer, Iberdrola Renewables. But by 2011, the number of leks increased—mainly in the area just outside the project, suggesting that lekking birds were avoiding the area beneath the turbines. The total number of birds within a mile of the turbines returned to preconstruction levels.

The Elk River wind project proved controversial among landowners who didn’t like the look of towering turbines marching across the landscape. Yet that wasn’t the end of it. In 2012, the Caney River project—a third larger than Elk River—began operating 11 miles to the southeast. As more wind developers drew a bead on the Flint Hills, then-Gov. Kathleen Sebelius negotiated a voluntary deal with the wind industry to steer clear of the Flint Hills as far south as the Elk River project. The next governor, Sam Brownback, extended what had become known as the “governor’s box” south all the way to the Oklahoma border.

That voluntary agreement with the wind industry has held, though current Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly has been pressed by at least one county board to allow more wind projects into the Flint Hills.

“Every time we get a new governor the issue comes up again,” says Brad Loveless, Kansas secretary of parks, wildlife and tourism. “I can tell you that the [current] governor is supportive of protecting the Flint Hills.” Loveless acknowledges that the agreement could fall apart with a change in the political winds or the next election. Because nearly all the Flint Hills is privately owned, the deals are purely voluntary—and there are no proposals to ban development on private property. Says Loveless, “I don’t imagine there’s a lot of appetite on the part of the Legislature to legislate at protecting certain areas.”

As it stands now, the state has a limited official role in wind-power siting, or controlling where wind energy gets developed, Loveless says.

“All it takes to make a project work is a developer willing to site a project, a county that’s willing to accept it and approve it, and somebody that’s willing to buy the power,” Loveless says. “Given the right circumstances, all those things could come together and they could put wind power in a really bad spot.”

A Way of Life

In Oklahoma’s Osage Hills, which doesn’t have the protection of a “governor’s box” to advise where wind energy should or shouldn’t be developed, Ford Drummond woke up one morning to find a wind farm going up on a neighbor’s ranch. The turbines were erected by a Kansas company that avoided the Flint Hills, sure enough, but simply marched south across the state line.

Now the turbines are close enough that if a tower crashed it would take out Drummond’s fence.

“We still have beautiful tallgrass prairie landscapes, and that to me is one of the worst things about the wind farm,” says Drummond, who is also a board member of the Oklahoma Nature Conservancy. “I’m not anti–wind farm per se, but there are certain places where they belong and certain places where they don’t.”

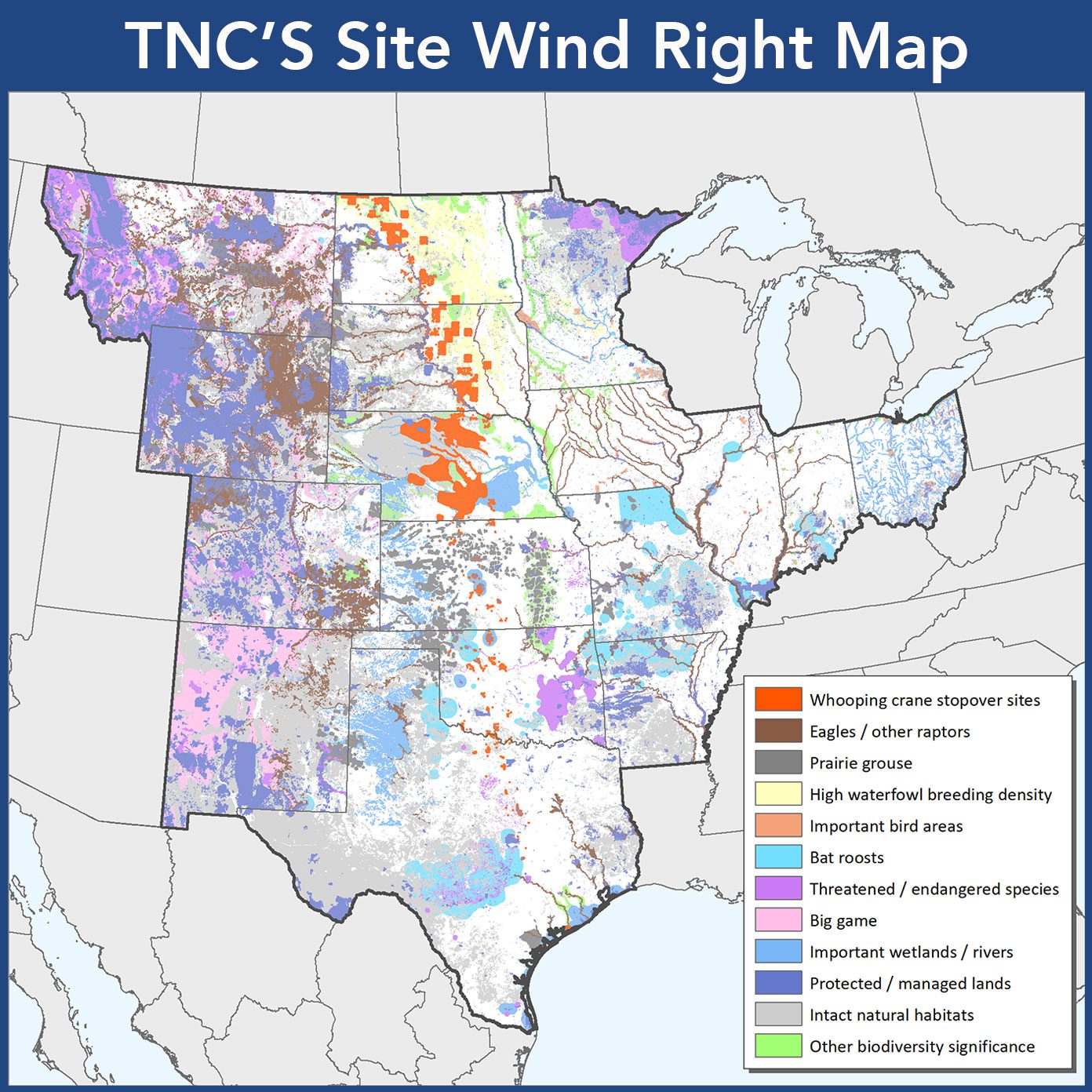

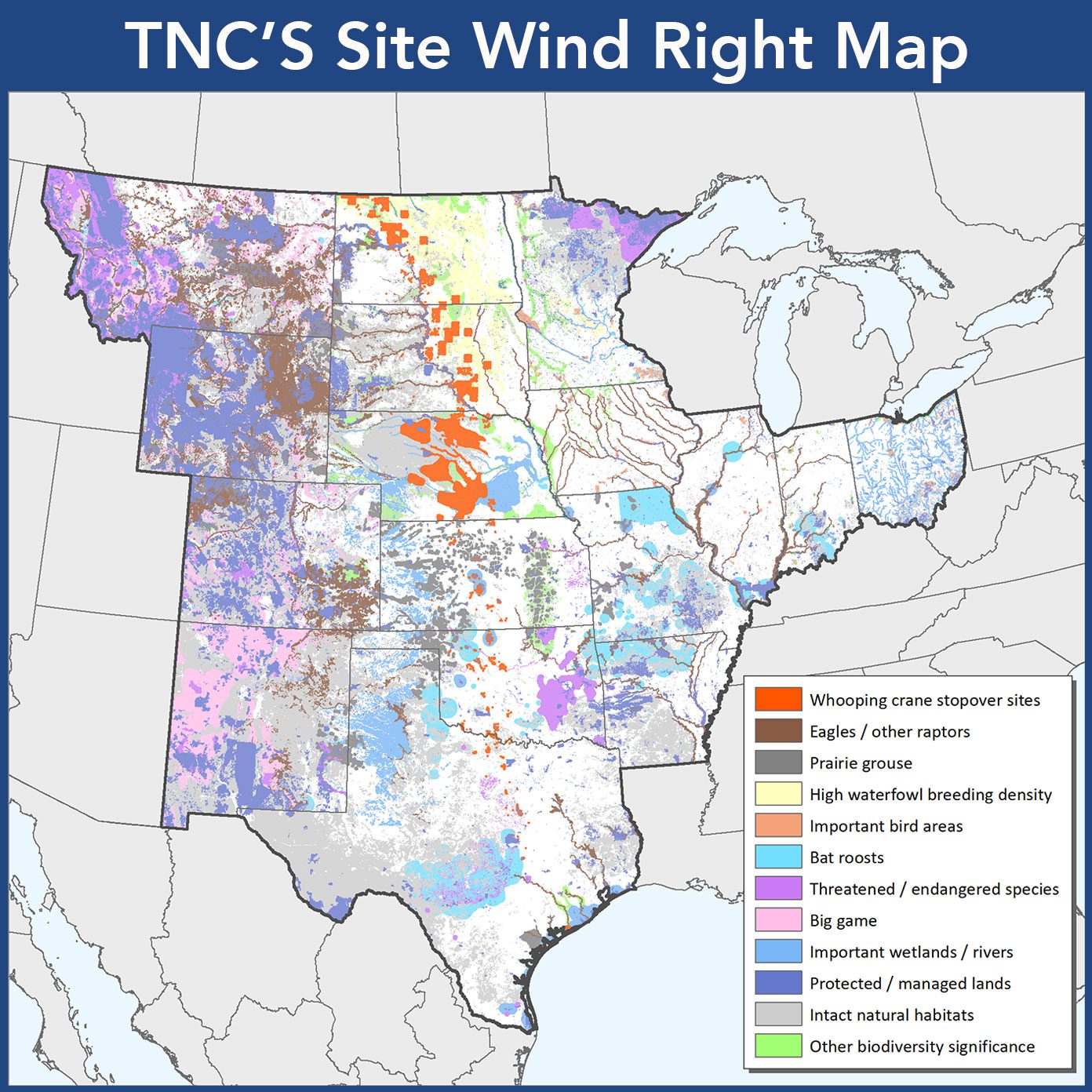

That is the idea behind a Nature Conservancy effort called Site Wind Right. It began nearly 10 years ago as Brian Obermeyer and colleagues were trying to respond to wind development.

“The Nature Conservancy, from the very beginning, made it very clear we were supportive of wind power,” says Obermeyer. “This is just an effort to help siting in a way that avoids key habitats.”

The Conservancy crew puzzled over how to mitigate the effects of wind farms on areas they identified as ecologically valuable, such as large tracts of native prairie or playas.

“What we found was that there are some places you just can’t [mitigate wind-farm effects]…they’re irreplaceable,” says Obermeyer. “You cannot recreate an intact native grassland. You just can’t mitigate that.”

But by looking at maps, they realized Kansas had more than 6 million acres of thoroughly roaded and plowed farmland, largely to the west of the Flint Hills where wind development would pose little additional threat to wildlife and rare ecosystems. That’s enough for 134 gigawatts of installed wind capacity, roughly equivalent to 100 conventional power plants—far more than even the most optimistic forecasts for state wind production.

“Nineteen percent of the state with viable wind resources wouldn’t require any [ecological] mitigation at all,” Obermeyer says. That’s an area larger than the Flint Hills.

Next, Obermeyer turned to Chris Hise, associate director of conservation for the Oklahoma Nature Conservancy chapter. Hise worked his GIS skills and expanded the Kansas Site Wind Right map to 17 states across the nation’s “wind belt,” from Ohio to Texas to Montana. In nearly all of those states there are vast areas with high wind-energy potential that don’t conflict with conservation goals.

Nathan Cummins, the Conservancy’s Great Plains renewable energy strategy director, says the organization is promoting Site Wind Right with states and wind developers through organizations such as the American Wind Energy Association and the American Wind Wildlife Institute. One power company—Evergy, which delivers electricity to more than 1.6 million customers in Kansas and Missouri—is directly using Site Wind Right maps in wind-siting decisions.

“On the whole, it’s a very positive message,” says Hise. “It looks like we have the potential to produce something like 1,000 gigawatts of wind capacity, plenty of room to develop wind without, hopefully, having negative impacts on wildlife.”

“The Only Way”

Some Flint Hills ranchers are taking their own actions to permanently protect their grasslands.

Josh Hoy (Jim Hoy’s son) has sold conservation easements covering almost half of his family’s 7,000-acre Flying W Ranch near the town of Clements in the heart of the Flint Hills. And within the next two years, “every acre will be protected,” says Hoy.

The concept behind a conservation easement is simple. The landowner sells development rights on property to a conservation organization and receives a payment. In return that land must be kept as it is in perpetuity. It’s an effective means to protect habitat in a landscape dominated by private property. So far Obermeyer says The Nature Conservancy and other partners have secured about 110,000 acres of conservation easements in the Flint Hills.

“It’s really the only way to protect rangeland and ranch land long term,” says Hoy. “No matter what our intentions are, our children’s, our grandchildren’s intentions are going to be different. If that property is protected and held together by an easement, then they can still get the benefits from it. They just can’t divide it up and break it up and turn it into housing tracts or put industrial parks on it or put in industrial wind or fracking or any of those things that degrade and destroy.”

Ultimately, the fight in the Flint Hills is a struggle over a near-pristine prairie remnant—the last 4% of the tallgrass—and a way of life.

Annie Wilson owns the 2,000-acre Five Oaks Ranch in the southern Flint Hills, most all of it native prairie. In college during the 1970s she was a huge proponent of wind power.

“I was sure that we all would be using wind and solar exclusively by the end of the century,” she says. But when she realized the scale of wind development, she began to fear its environmental impact.

“I don’t believe in the term ‘wind farm.’ I think that’s a really deceptive euphemism,” she says. “It seems to me that you would want to site these systems in places that do not contain the last few percent of a threatened ecosystem, as is the tallgrass prairie.”

Wilson is also a songwriter. Sometimes she sings about the prairie that surrounds her.

“One of my songs is ‘The Clean Curve of Hill Against Sky,’” she says. “The idea is that there are just so few places left on earth that you can see that, but you can see it here, where there are no trees, no towers, no buildings…just the prairie horizon.”

Freelance writer Greg Breining writes about wildlife, the environment, health, and science. His latest book, Wolf Island, describes the early days of the long-running wolf–moose research study on Isle Royale.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you