Deepwater Horizon: Ten Years After America’s Biggest Oil Spill Disaster

By Scott Weidensaul

Raccoon Island has been restored in the last ten years and pelicans are nesting there again. Photo by Amy Shutt. September 18, 2020From the Autumn 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Raccoon Island—about 160 acres of sand and marsh shaped like a scimitar blade—is the westernmost of the barrier chain known as Isles Dernieres, an hour’s boat ride from the nearest solid land in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana. Juita Martinez admits that Raccoon isn’t exactly the kind of island paradise that appeals to most people. “It smells like fish and pelican poop,” the 27-year-old doctoral student from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette says with a laugh.

But for Martinez, who walks the length of this remote island and four others off the Louisiana coast for her research on pelican nesting success, Raccoon is something special.

“It’s pretty much covered from east to west in pelican nests. There are 10,000 [pairs of] Brown Pelicans nesting on it, give or take,” she says. “As I’m walking through, I flush all the Laughing Gulls, I’m getting bombed with Laughing Gull poop, and on the dune areas of the island, you have your skimmers and terns dive-bombing you as you try to walk through and create the least amount of disturbance possible.”

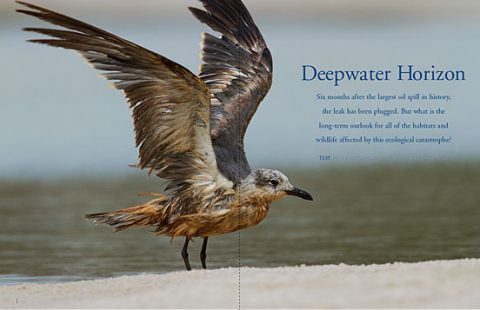

Ten years ago, the scene on Raccoon Island, and across the northern Gulf of Mexico, was very different. Oil from the April 20, 2010, explosion of the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig and subsequent well blowout washed across the Isles Dernieres and many of the other waterbird colonies Martinez now studies, fouling beaches and marshes from southern Louisiana to western Florida. As many as 1 million birds—and countless fish, marine invertebrates, sea turtles, marine mammals, and much more—perished in the disaster.

The Deepwater Horizon blowout, which gushed for 87 days and wasn’t declared fully sealed until September 2010, remains the most calamitous oil spill in American history—nearly 134 million gallons of oil, the equivalent (in terms of volume) to 12 Exxon Valdez-level catastrophes, creating a slick that eventually covered 15,300 square miles. (A recent study concluded that invisible yet toxic plumes of oil actually spread over a much larger area.) Some 1,300 miles of beach, from northwestern Florida to eastern Texas, were fouled by oil, much of which wound up trapped in sediments on the ocean floor and coastlines, stirred up by storms for years thereafter.

Scenes from 2010: the Deepwater Horizon oil rig on fire. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard.

Scenes from 2010: An oil-covered barrier island in Louisiana’s Barataria Bay. Photo by Gerrit Vyn, on assignment in 2010 documenting the Deepwater Horizon oil spill damage to birds and habitat for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s conservation media program.

Scenes from 2010: An oiled and emaciated young Brown Pelican on Raccoon Island. Photo by Gerrit Vyn, on assignment in 2010.

A sample of more than 2,000 Gulf fish of 91 species, collected across seven years following the spill, found the most toxic component of crude oil in all of them. After a decade, researchers and wildlife managers are still grappling with the spill’s long-term impact—trying to document its overt and insidious effects even as billions of dollars in fines and criminal and civil settlements are being spent on what is perhaps the most ambitious ecological restoration undertaking in history.

Martinez’s pelican colony visits are a small part of that process, as she compares nesting success on islands that have been enlarged and restored using Deepwater settlement funds with other islands that are quickly eroding into the sea. Perhaps not surprisingly, she has found that pelicans on the three restored islands she surveys have much better nesting success than on the two unrestored islands in her study.

Ten years ago, Royal Tern fledglings in a nesting colony on Queen Bess Island were too oiled to fly out to sea and search for food. Photo by Gerrit Vyn.

In June 2020, a new generation of Royal Terns on Raccoon Island successfully fledged, the beneficiaries of millions of dollars of restoration work to rebuild the sandy dunes. Photo by Amy Shutt.

And she’s not alone. Researchers, conservation organizations, and state and federal agencies across the northern Gulf are working with coastal engineers to create or restore habitat for beach-nesting birds such as Black Skimmers and Least Terns, colonial waterbirds like egrets and herons, secretive marsh-dwellers such as rails, and dozens of species of shorebirds. And because the Gulf is a hemispheric migratory nexus, drawing birds from thousands of miles away, biologists in Minnesota, the Dakotas, and the Canadian Maritimes are also working to understand and undo the damage to populations of birds such as Common Loon, Black Tern, and Northern Gannet—species that were killed by the thousands 10 years ago while overwintering in Gulf waters.

Losing Environmental Protections

Officially, a government assessment concluded that roughly 100,000 birds were directly killed by the spill, though independent scientists have estimated that the true number was 10 or 20 times higher. As a consequence of the spill, BP and its business partners paid billions of dollars in penalties, $16.67 billion of which is funding a comprehensive restoration of the northern Gulf of Mexico—a process that is just now gathering steam after years of litigation and planning. While biologists acknowledge a hard-edged fact—that most of the restoration focus is on bolstering coastal features like barrier islands to protect human infrastructure farther inland—the work is creating or improving tens of thousands of acres of critical bird habitat. The restoration is designed not only to mitigate the damage done 10 years ago in the BP spill, but to provide resiliency against rising sea levels and intensifying storms driven by climate change.

An Unknowable Death Toll for Birds

The Deepwater Horizon blowout produced searing images of oiled pelicans, gannets, egrets, and other large birds, but the true extent of the number of birds killed outright, sickened, or debilitated by exposure to petro-toxins and other contaminants, or driven from their nests, remains unknown. No one could tally, for example, how many pelagic seabirds far from shore, or marsh birds such as rails hidden in coastal wetlands, perished unseen and unseeable.

The disaster began in April 2010, when a mobile drilling rig at BP’s Macondo well, 49 miles off the Louisiana coast, exploded—killing 11 workers, catching fire, and sinking. Almost 5,000 feet below the surface, the well’s blowout preventer failed, and oil gushed unimpeded for months. Some 1.8 million gallons of dispersant chemicals, posing their own risks to Gulf ecosystems that were poorly understood, were released in attempts to break up slicks. In 2011, a year after the disaster, 490 miles of Gulf coastline were still contaminated by oil.

Quantifying the immediate avian death toll is a challenge in any oil spill. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which estimated bird mortality in order to determine the damages BP had to pay under the 1990 Oil Pollution Act, placed the total kill at between 63,000 and 102,000 birds of 93 species, but acknowledged that the figures “represent only a portion of the bird injury.” On the other hand, a trio of independent environmental researchers, including the chief scientist for Defenders of Wildlife and a marine chemist who spent most of his career with NOAA, used a suite of statistical models based on USFWS data to put the total number of dead birds at about 1 million, and possibly as high as 2.6 million. Four species—Laughing Gulls, Northern Gannets, Brown Pelicans, and Royal Terns—made up the majority of the dead, the team said, with nearly a third of the region’s Laughing Gulls dying, along with 13% of Royal Terns and 12% of Brown Pelicans. Yet even these scientists warned that their figures were still likely to be underestimates, especially with many of the same groups, like pelagics and marsh birds, that the USFWS had a hard time accounting for. (BP disputed those findings, noting that the research was paid for by law firms whose clients had claims against the company, but other scientists not involved in the study said they found many of its conclusions reasonable.)

Nearly a third of the Laughing Gulls in the oil-spill area were estimated to have died. Photo by Gerrit Vyn.

Today healthy Laughing Gulls are seen all along Gulf Coast beaches, another of the many bird species that benefit from the restoration work on Louisiana’s barrier islands. Photo by Van Remsen/Macaulay Library.

Regardless of methodology, in the case of Deepwater, coming up with a firm avian mortality figure was complicated by the fact that 80% of the spill remained more than 25 miles offshore, meaning that most of the oiled or dead birds never reached the beach. (Only about 3,000 carcasses were recovered.) Limited pre-spill surveys suggest that up to 60% of the birds inhabiting offshore waters were small, darker-plumaged species such as Black Terns and various storm-petrels that would be especially hard to spot in the slick, which may explain why only nine dead Black Terns were found. Intentionally burning off oil on the ocean’s surface likely destroyed many carcasses floating in the slick, scientists said. As high tides carried the oil deep into coastal marshes far from any road access, experts could only guess at the damage to secretive species such as rails and bitterns. Almost a year after the spill, researchers documented that nearly a quarter of Common Loons wintering in the disaster zone showed visible oiling, as did lesser numbers of White Pelicans and Northern Gannets, suggesting that oil was still very much a danger in the Gulf.

But in the wake of the spill, some population-level changes were obvious. Many major breeding colonies, such as the Brown Pelicans and Royal Terns on Queen Bess Island near Grand Isle, Louisiana, took a direct hit in the middle of the nesting season. While a handful of chicks fledged, most nests failed.

Then there are the more subtle effects that emerge over time, especially those involving environmental contaminants. A 2017 overview by academic and federal agency scientists, synthesizing dozens of studies focusing on the toxicity of oil and dispersant chemicals from the Deepwater spill on birds, concluded that “the combined effects of oil toxicity and feather effects in avian species, even in the case of relatively light oiling, can significantly affect the overall health of birds.” Beyond obvious problems to birds caused by oil exposure, like feather damage and loss of thermoregulation, the scientists pointed to such impacts as interference with fat deposition and metabolism; increased inflammatory responses and a suppression of the immune system; and hemolytic anemia, which causes irreversible and life-threatening damage to hemoglobin. This often-fatal form of anemia was detected in egrets, skimmers, pelicans, and rails with light or no feather oiling. Seaside Sparrows, collected a year after the spill, showed the isotopic signature of oil in their tissues and crop contents, and sparrows from oiled sites had lower reproductive success in the years after the spill.

Scientists also expressed concern about the long-term impact of toxins like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), considered the most toxic components of crude oil, which linger for decades after a spill and can cause cancer, muscle damage, metabolic problems, and much more. PAHs may be particularly harmful to shorebirds because their foraging behavior, probing in the sand and mud, is more likely to bring them into contact with weathered buried oil. One research team estimated that more than 1 million migrant shorebirds of 28 species, including many already in serious decline, were potentially exposed to Deepwater oil within a year of the spill. Both Sanderlings and Western Sandpipers showed losses in body mass—in the case of some Sanderlings, more than five times greater loss than control birds—when exposed to PAHs and weathered Deepwater oil; the researchers noted that this would be especially dangerous during spring migration, when time is of the essence and migrants are pushed to physiological limits. In a separate study, they found that Sanderlings feeding in areas with high PAH contamination fueled up less quickly than in uncontaminated areas. And the effects climb the food chain; other scientists found significant PAH levels in migrant Peregrine Falcons, which feed heavily on shorebirds, along the Gulf Coast in the autumn following the spill.

Much also remains unknown about the effects of the chemical dispersants, which were used in unprecedented quantities to break up oil slicks in the Gulf. Experiments with eggs of captive Mallards suggested that as deadly as weathered oil was to developing duck embryos, the combination of oil and dispersant chemicals was even more toxic, though dispersant alone could also kill or impair embryos.

The evidence for local population declines and health impacts to birds laid the groundwork for billions of dollars in settlement funds that have, in the past four years, begun to flow toward a breathtaking array of restoration projects to remediate the Deepwater Horizon oil spill’s damage and make the coast more resilient. Scientists say some of the early recovery work has been hamstrung by a lack of basic information about natural systems in the Gulf, and a lack of coordination in collecting data. But in response, scientists from Louisiana to Florida have rallied in common cause—a unified, first-of-its-kind effort to better monitor the region’s birdlife among various local, state, and federal agencies and nonprofit groups that don’t have a history of working together.

Closing the Gaps in Bird Surveys

From the Archive: Autumn 2010 Living Bird

In 2016 BP (along with rig owner TransOcean, well co-owner Anadarko, and Halliburton, which provided cementing services at the site) agreed to pay $20.8 billion to settle all civil and criminal claims under the Clean Water Act, the 1990 Oil Pollution Act, and other federal statutes—the largest environmental settlement in U.S. history. (That figure, eye-popping as it is, does not include another $500 million BP agreed to pay to fund a 10-year research initiative in the Gulf, or an estimated $14.8 billion in private claims. BP has pegged its total costs from the spill at more than $65 billion.) The fines included $100 million specifically designated for use in bird restoration, levied under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. (The Trump Administration is now attempting to change the MBTA in ways that would let future polluters off the hook for bird deaths.) Altogether, some $8.8 billion from the settlement funds was targeted for direct ecological restoration, unwinding damage from the spill, and improving Gulf ecosystems and wildlife populations.

But undoing the damage means knowing where things stood before the Deepwater Horizon gusher erupted—and scientists have only a sketchy idea. A research team studying Common Loons in the years after the spill found high levels of PAHs in the birds, but they concluded that “without pre-spill data, it is impossible to know the previous annual pattern of PAH contamination in top trophic predators … and therefore it is challenging to quantify how much oil (and PAHs) from the [Deepwater spill] influenced our results.”

That was a theme I heard again and again from the 18 scientists, agency biologists, conservation group leaders, coastal engineers, and others with whom I spoke for this article. A lack of pre-spill, baseline data, collected in easily comparable ways, has hobbled their ability to really understand the longterm impact of the Deepwater disaster on bird populations. Survey techniques varied so much from state to state that comparing, say, counts of colonial wading birds from Louisiana with those from Texas was like comparing apples to oranges.

“Although we had data [on bird populations], it was not coordinated, not any sort of collaborative effort, so that makes it really difficult to pin down a baseline from before the spill,” said Randy Wilson, station leader for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Mississippi Migratory Bird Field Station. “I don’t think anyone’s ever said, ‘Hey, can we get all the shorebird people to use the same protocol?’ ”

If there’s a silver lining, it’s that those gaps are beginning to close. Hundreds of collaborators from public and private entities have formed an immense cooperative venture, the Gulf of Mexico Avian Monitoring Network, chaired by Wilson, to get everyone in the five-state northern Gulf region pulling in the same direction, collecting data in comparable ways, and working in a coordinated fashion on monitoring strategies for 68 bird species of conservation concern.

These efforts began in 2014, but the ambitious, big-picture approach to bird monitoring is only now gathering steam—as is restoration work in the Gulf.

If You Build It, They Will Come

Even though the Deepwater Horizon oil spill happened a decade ago, the vast majority of habitat rebuilding in the Gulf is just getting underway.

“You can imagine that the bureaucratic process of just getting the anchors in place to disburse those funds took quite some time, so it’s really only been four years since big restoration started to happen,” said Kara Fox, director of Gulf restoration for the National Audubon Society. “But given all that, we’ve absolutely seen some restoration success stories. I’m always amazed doing this work, and especially since the BP oil spill, just how resilient the environment is.”

There’s a little of an “If you build it, they will come” vibe at work in Gulf restoration, where eroding coastal marshes and barrier islands—problems that were well underway years before the oil spill—meant that many birds were already short on real estate before the spill fouled what little was left.

By adding 3.3 million cubic yards of dredged sediment to Caminada Headland, a 14-mile-long beach southwest of Grand Isle that was retreating by 35 feet a year, engineers created 330 acres of habitat that was quickly occupied by nesting Least Terns when the project was completed in 2015, said John Tirpak, a USFWS biologist who coordinated early restoration efforts in the Gulf. Work at Caminada and nearby Whiskey Island—all part of the Caillou Lake Headlands project, the largest restoration attempt to date in Louisiana—was funded out of early settlement money that BP put up in 2011 to jump-start recovery operations.

“It’s a really important area for Wilson’s Plovers, Gull-billed Terns, Black Skimmers,” Tirpak said. “As soon as the equipment was coming off the island, they were taking up residence and breeding.”

Another restoration success story is Queen Bess Island on Barataria Bay in Louisiana, one of Juita Martinez’s prime pelican study sites. Queen Bess is where Brown Pelicans, extirpated from the state by DDT in the 1960s and listed under the federal Endangered Species Act, were reintroduced in 1968.

During the more than half-century since the reintroduction, Queen Bess Island became one of the most important pelican colonies on the Louisiana coast. In November 2009, thanks in significant measure to Queen Bess, the Brown Pelican population had recovered to the point where the species was formally delisted from ESA protection. Five months later, the Deepwater Horizon rig exploded.

“Queen Bess was kind of right in the crosshairs of the BP oil spill,” said Todd Baker, coastal resource scientist manager for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. Barataria Bay was among the most heavily oiled areas anywhere in the Gulf. Queen Bess Island—with more than 3,000 nesting pairs of pelicans, Louisiana’s third largest colony and up to 20% of the state’s population—was hit by slicks multiple times.

“It truly was ground zero in terms of a marsh and a wildlife impact,” said Baker.

Worse, the spill was bad luck piling on habitat loss that was already occurring. Despite their recovery success after ESA listing, pelicans have more recently suffered a multiplicity of problems, of which Deepwater was only the most dramatic. Pelicans only colonize a few islands in the northern Gulf, most of which are rapidly disappearing. (Pelicans prefer small islands that can’t support mammalian predators like raccoons and coyotes.) Massive alterations like dams in the Mississippi River system have dramatically reduced sediment flow into Louisiana’s delta, which now erodes far more quickly than new land can accrue. Sea-level rise further eats away at what remains. Once-extensive coastal marshes in the state have been chewed into millions of fragments by navigation channels, allowing wave action and ship wakes to penetrate deep into what had been contiguous marsh.

Pelican numbers plateaued in the early 2000s in Louisiana with about 19,000 breeding pairs, according to Rob Dobbs, LDWF’s nongame avian ecologist. Their numbers dropped after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, recovered, then fell again after the Deepwater blowout. Although the overall pelican population in the state bounced back to prespill levels within three years, Dobbs said, the number of colonies has fallen from 20 in the state to 15 because of coastal erosion, and the land available for the pelican colonies that remain has been shrinking rapidly. For instance, even after the spill cleanup, less than five acres of Queen Bess’s 36 acres were usable for nesting, with much of the rest eroded into the sea, leaving just the rocky rim of its former outline.

With almost $19 million in oil spill settlement funds, engineers at Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, working closely with Baker and LDWF biologists, redesigned the island for maximum avian benefit and long-term stability in the face of inevitable rising sea levels.

Beginning last September, just as the nesting season ended, crews barged in dredge sand to fill in the rock rim, creating 30 upland acres planted with matrimony vine, groundsel bush, and marsh alder as prime nesting habitat for pelicans. Another seven acres of dredge sand was left as bare, high dunes to provide habitat for beach-nesting Black Skimmers and Royal and Least Terns. Work finished in mid-February, as pelicans and other birds were already gathering around the island for the 2020 nesting season—and as soon as the workers left, Baker said, the birds moved in.

“The response in year one has just been off the charts,” Baker said. Compared with 2018, the last pre-restoration census taken on the island, Queen Bess had about 1,000 more pelican nests this spring (though Baker cautioned that the counts are not exactly comparable due to changes in survey protocols).

One of those new birds was A04—a banded male Brown Pelican found injured in Mississippi in August 2010 following the Deepwater spill, and then cleaned, rehabbed, and released. A04 was found this past spring nesting on Queen Bess, the first pelican there known to have survived the spill.

The restoration work further proved its value this past June, when tropical storm Cristobal hit Louisiana with powerful winds and high storm surges. Given the storm damage inflicted on levees and beaches in the area, some biologists feared the newly rebuilt island might be washed away entirely. Instead, Baker found it intact, and about 70% of the pelican chicks on it survived, thanks to its now-higher elevation. Black Skimmer, Laughing Gull, and tern nests closer to the water were destroyed, but those birds were already renesting by late June, Baker reported.

The next big bird-restoration project this autumn is Rabbit Island in southwestern Louisiana’s Cameron Parish, a key colony connecting pelican populations in Louisiana with Texas. Rabbit has lost more than a third of its once-300 acres to erosion, now lies barely a foot above the mean water level, and is often flooded by high tides.

“In many years, we have no successful nesting on that island due to inundation,” Baker said. Plans call for spending $16.4 million in spill settlement funds to restore about 88 of the remaining 200 acres, an ambitious step up from much smaller Queen Bess Island. By raising the elevation of the island within its existing footprint, planners say, the restoration will benefit a variety of colonial waterbirds and shorebirds, including Roseate Spoonbills, American Oystercatchers, Reddish Egrets, and Tricolored Herons, as well as pelicans.

Effects Far Beyond the Gulf

The Gulf of Mexico is one of the world’s great bird migration thoroughfares. An estimate by Cornell Lab of Ornithology scientists, using years of highly precise Doppler radar data, puts the annual spring migration through the region at more than 2 billion birds. As a result, the impact of the Deepwater Horizon tragedy was felt far beyond the five states that rim the Gulf—for example, among Black Terns from the prairie potholes of the Dakotas, Northern Gannets nesting on the cold cliffs of Newfoundland, and Common Loons in Minnesota.

Black Terns are among the most abundant offshore pelagic birds in the northern Gulf. No one is sure how many were lost in the spill; only a few Black Tern carcasses were recovered, but because they are small, dark-plumaged birds that stay far from land, finding dead Black Terns is unlikely. To make up for unknown tern losses from the Deepwater Horizon disaster, $6 million in settlement funds are being directed to voluntary wetland and grassland conservation easements in the Dakotas, where the terns nest. The Deepwater money should provide a tern-specific boost of thousands of acres to the roughly 3 million acres that are placed in conservation easements there. The easements are targeted toward protecting the larger, more hydrologically complex marshes the terns prefer, said Neal Niemuth of the USFWS office in Bismarck, North Dakota.

Much farther from the Gulf, one biologist shuddered when he saw images from the Deepwater Horizon spill. In 2010 William Montevecchi saw a news article with a picture of an oiled Northern Gannet—a species this New England native has been studying for years in Newfoundland, where he’s a professor at Memorial University in St. John’s.

“It was just a shocker, like, ‘Wow, we’re involved here,’ ” he said.

Gannets were one of the four most frequently oiled bird species found during the disaster, and subsequent tracking data now suggests that up to a quarter of North America’s gannets winter in the Gulf. Soon after the spill, Montevecchi found himself directly involved in assessing the impacts, conducting dozens of 25-mile-long transect surveys by boat off Louisiana to look for oiled gannets and other birds. As a result of that work, conducted as part of the federal natural resources damage assessment, Montevecchi and his colleagues estimated that about 2.5% of the gannets that were exposed to oil died; other researchers pegged the overall loss of wintering gannets in the Gulf at 8%.

Because the spill occurred in April, most of the gannets remaining there were immature birds, which means most breeding adults in the population likely weren’t impacted, Montevecchi said.

“If you were to look for a population effect, it would be a lagged one, a long-lagged one, maybe five years or more,” he said, because it takes five years for gannets to reach maturity and start breeding on their few colonies in Quebec and Newfoundland.

“I can honestly tell you, though, we haven’t seen any blip as a consequence of [the spill],” said Montevecchi. That’s not to say that gannets are doing fine, however. The species has suffered a succession of very poor breeding seasons in Canada since 2012, which are likely tied to warming sea temperatures and changes in forage species like mackerel. Teasing out the effects of the spill, in the face of so many other pressures, has been difficult, Montevecchi said.

Another hard-hit species was the Common Loon. NOAA’s mortality figures put the number killed in the spill between 600 and 1,000 loons. A more recent estimate suggests 11% of the wintering loon population may have died. Many of these loons were part of a population that nests in the western Great Lakes region. In Minnesota, wildlife biologist Carrol Henderson recalls hearing about the spill 10 years ago and thinking: “That’s really too bad. It’s a big disaster for the local wildlife of the Gulf.”

“Then the reality set in,” Henderson said. “Wait a minute, we [in Minnesota] have a lot of birds that migrate to the Gulf.”

In the years immediately after the spill, Henderson and his colleagues in the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources used satellite transmitters and geolocators to show that many of Minnesota’s loons were, in fact, spending the winter precisely in the disaster zone.

“The ones we had from Minnesota, they were right in the bullseye,” Henderson said. The tracking data also showed the loons were foraging up to 110 feet deep, feeding on benthic organisms where the oil had gathered on the bottom.

By connecting the oil spill to Great Lakes loons, Henderson was able to make the case for spending money on remediation work in Minnesota from the multi-billion-dollar settlement by BP and its business partners. The idea is to replace those loons lost to the spill by reducing mortality up north.

Henderson (now retired but still working with loons) and his colleagues are using a three-year, $7.7 million grant from the settlement fund on an effort with two aims. One is to reduce the significant rate of lead poisoning among loons through a “Get the Lead Out” educational campaign aimed at anglers. His team also hopes to boost loon productivity by working with lake associations across Minnesota to formulate site-specific loon management plans, and to purchase or otherwise protect lakeshore property from development. If the program is successful, the grant can be renewed for up to 15 years.

For Birds, a Brighter Day?

So, where do the Gulf’s birds stand, a decade after the spill?

It’s frustratingly hard to say. Pelicans, which are big and relatively easy to count, and which were the poster child for species impacted by the disaster, appear to have rebounded. For other species, like gannets, the picture is muddied by the multiple other threats they face. For still others, like Black Terns, we’ll simply never know how bad the losses were, and all conservationists can do is try to bolster breeding populations as best they can. And no one has a handle on the extent to which petro-toxins like PAHs, which are still circulating widely in the Gulf ecosystem, are affecting birds and other wildlife.

On the other hand, it’s clear that the billions now in the pipeline for restoration have the potential to make a historic difference for birds in the Gulf, and the bulk of the restoration money is going to work that ultimately protects human communities and infrastructure from storms and rising seas as well.

While scientists working on these projects lament that it took a disaster of such scope to make ecosystem-level restoration possible, many of them said the efforts are coming just in time for many species of birds. Louisiana state biologist Todd Baker concedes that it’s exciting and rewarding to see, for example, how rapidly pelicans and other nesting birds have crowded into restored islands like Queen Bess.

But, he said, “it’s also incredibly alarming that so many birds respond so strongly to that habitat. It really shows how limited that habitat is, and that a lot more work is needed.”

For Juita Martinez, sweaty from the heat and splattered with bird droppings after counting pelican babies on a newly restored island, her overwhelming takeaway is one of gratitude.

“It’s an honor to be able to work on these islands,” she says, “to see these birds doing their thing that they’ve done for hundreds of years, and which most people don’t get to experience up close. I always feel so lucky.”

Pulitzer-nominated Scott Weidensaul has written more than 30 books about birds and natural history. His next book, coming in March 2021, will explore global migratory bird conservation.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you