Special Section: Recent Environmental Rule Changes and Rollbacks

Text by Anil Oza and Gustave Axelson; artwork by Jillian Ditner

September 28, 2020From the Autumn 2020 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

One year ago, a landmark study published in the journal Science made headlines around the world. The most robust population assessment of North America’s birds ever conducted revealed a stunning 29% decline since 1970—or almost 3 billion birds lost from the continental bird population in just a few decades.

“We were stunned by the result—it’s just staggering,” the study’s lead author, Cornell Lab of Ornithology conservation scientist Ken Rosenberg, told The New York Times in a front-page story published on Sept. 20, 2019.

On May 10, 2020, The New York Times published a list of 100 federal environmental rules in the United States that the Administration has reversed or is in the process of reversing. The rollbacks range from granting federal permission for more air pollution and greenhouse-gas emissions to stripping protections for wildlife and waters. Bedrock American environmental policy dating back to the Nixon, Wilson, and even the Theodore Roosevelt Administrations have been chipped up and broken apart over the past four years.

The onslaught has included direct attacks on bird conservation policy, such as the crippling of the 102-year old Migratory Bird Treaty Act and weakening of the Endangered Species Act. Bird populations are also likely to be affected by the weakened protections for America’s lands and waters. Birds pay dearly when ecosystems are compromised and polluted.

The next four years present an opportunity to foster policies that rebuild and restore America’s bird populations, and avoid what Rosenberg and his study coauthors warned us about—a “collapse of the continental avifauna.”

Bedrock Environmental Policy Is Crumbling

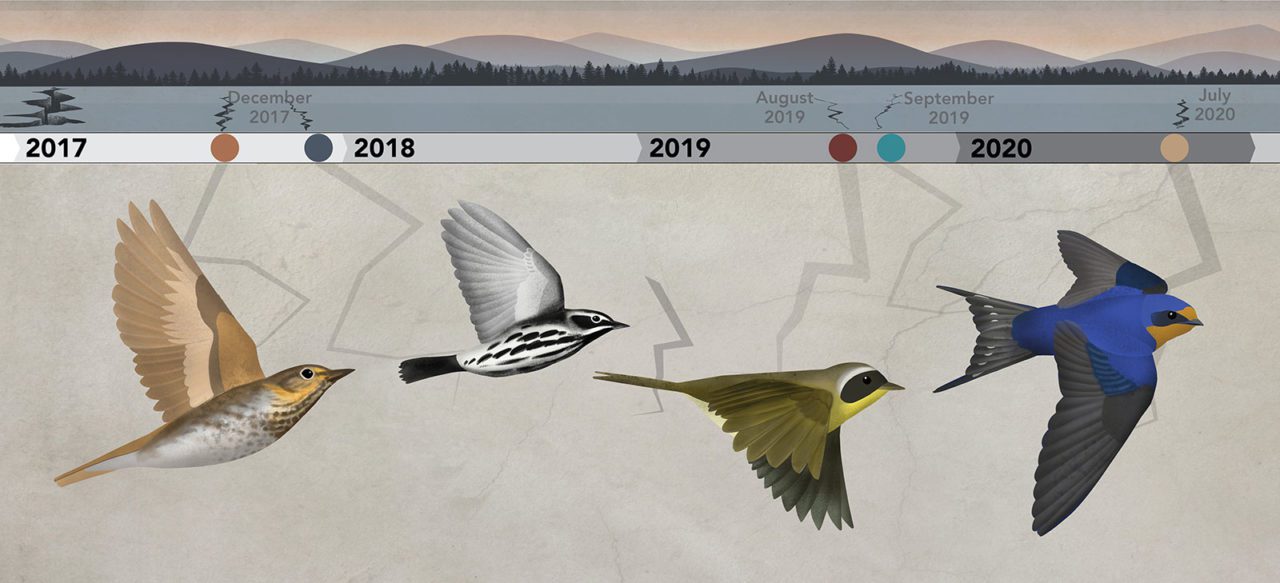

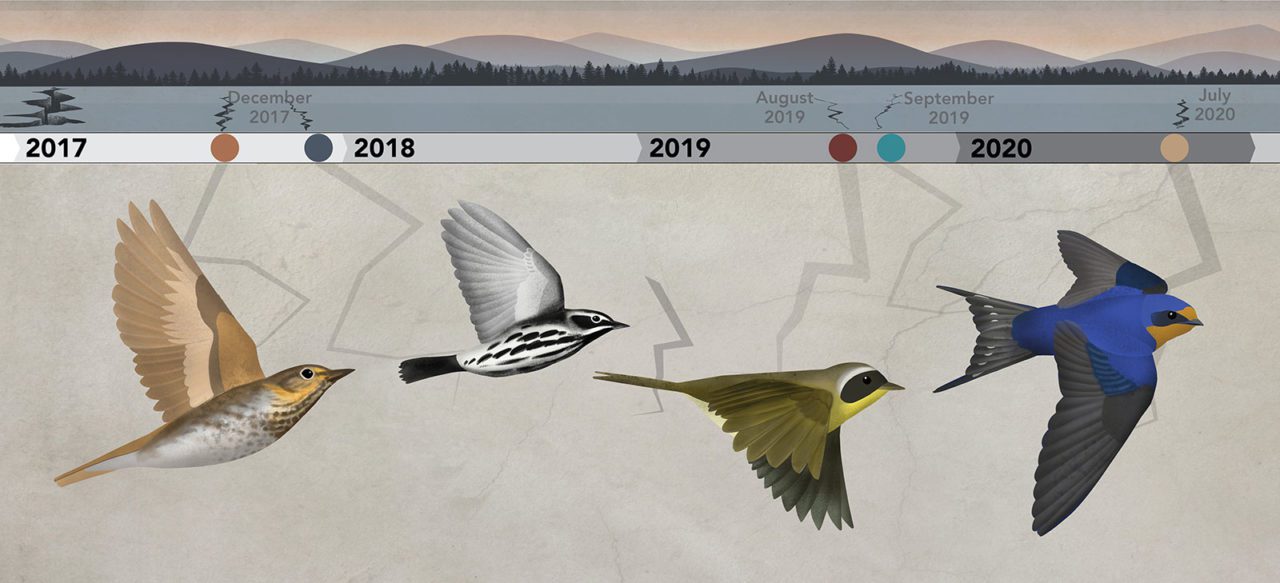

Among the 100 environmental rules rolled back over the past four years, there are several areas where weakened federal policy will exacerbate bird declines.

Weakening the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (December 2017)

More on Environmental Policy

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act was born with President Woodrow Wilson’s signature in 1916, a pledge between the U.S. and Canada to protect the migratory birds of North America from unregulated killing, or take. In a 2018 essay for Living Bird, Lynn Scarlett— former deputy secretary of the Interior under President George W. Bush—wrote about that long-standing definition of take: “For at least five decades, Republican and Democratic administrations alike have understood the Act to prohibit the ‘taking’ and ‘killing’ of birds … not just against hunting without permits, but also against ‘incidental take’ from foreseeable harms like oil spills, wind turbines, and transmission lines.” The MBTA triggered $100 million in penalties against the companies responsible for the Deepwater Horizon oil well blowout, which killed 1 million birds.

In December 2017, the Interior deputy solicitor issued a memorandum excluding incidental take from MBTA enforcement, meaning that industry would no longer face penalties for bird kills caused by negligence. In August 2020, a federal district court judge struck down the solicitor’s opinion. However, at press time, Interior appeared to be moving forward with a rule change to exclude incidental take from the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Analysis

“Roughly one billion birds are already killed by industry activities every year,” says Amanda Rodewald, conservation science director at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “By weakening the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, that death toll will likely rise.” Rodewald has submitted scientific comments and testified before a House committee on the removal of incidental take from the MBTA. She says that the industries that pose the greatest threats to birds will no longer have an incentive to take proactive steps to reduce those threats and avoid violating the Act. For example, she says, energy companies have covered oil pits to prevent flocks of birds from landing and getting stuck in the wastewater. But if that practice were to stop, there are 172 bird species susceptible to getting trapped in oil pits that would suffer higher mortality rates.”

Dropping Protection for Public Lands (December 2017)

The Presidential legacy of protecting America’s wildest lands goes back to President Lincoln (who protected Yosemite Valley) and President Grant (who established Yellowstone National Park). Since President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act of 1906, establishing the presidential power to protect lands as national monuments, every U.S. president has grown the area of America’s protected public lands—until now.

In December 2017, the Administration reduced the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monuments in Utah by 2 million acres to open up areas to oil and gas extraction and mining (the largest rollback of federal land protections in U.S. history). The next year, the Administration reinstated previously canceled federal leases for copper-nickel mining within the watershed of Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area.

Analysis

“Public lands provide more than half of the occupied habitat for 300 bird species, most of which are already declining,” says Cornell Lab senior conservation scientist Ken Rosenberg. “We need to protect more habitat for them, not less.” Rosenberg has been a lead author on eight State of the Birds reports presented to the Department of the Interior. He says the Administration’s rollbacks on protected lands to make way for drilling, mining, and forest clearing will be particularly harmful to birds out West. “Gunnison Sage-Grouse, Sagebrush Sparrow, LeConte’s Thrasher … these are species with over 75% of their populations living on public lands,” Rosenberg says. He cites Pinyon Jays—a species that has already declined by nearly 80% since 1970—as a bird that is clinging to habitats managed by the Bureau of Land Management. “A quarter of all Pinyon Jays live on BLM lands,” Rosenberg says. “But now with the recent federal land sell-offs and rule changes, the future for Pinyon Jays looks especially bleak.”

Diluting the Endangered Species Act (August 2019)

The Endangered Species Act was signed into law in 1973, committing the United States to protecting and restoring species at risk of extinction. “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed,” President Richard Nixon said at the Act’s signing. Nearly half of the species on the Endangered Species list at that time were birds, including Bald Eagle, Kirtland’s Warbler, and Brown Pelican—all three of which have since recovered and been delisted.

In August 2019, the Administration finalized a set of rule changes that weaken the Endangered Species Act by removing automatic protections against take for species listed as threatened under the ESA. The ESA rule changes also make it harder to hold federal agencies accountable for activities that threaten the continued existence of an endangered species, and downplay the role of climate change in designating critical habitat under the ESA.

Analysis

“Recent rollbacks on many of the ESA’s most potent provisions will cause substantial harm to North America’s most vulnerable birds,” says John Fitzpatrick, executive director of the Cornell Lab. Fitzpatrick has studied endangered species biology for 40 years and served on Endangered Species Recovery Teams for the Florida Scrub-Jay and Hawaiian Crow. He points out that eliminating habitat protection requirements for threatened ESA species such as Red Knot, Piping Plover, and Florida Scrub-Jay will hasten their declines. Fitzpatrick also says that to minimize the role of climate change in protecting critical habitat is to ignore one of the fastest-growing threats to declining species. A bedrock principle of the Endangered Species Act, he reminds government officials, is that decisions must be based strictly on the best-available science.

Stripping Clean Water Act Protections (September 2019)

The Clean Water Act became law in 1972, at a time when two-thirds of America’s lakes, rivers, and coastal waters were so polluted they were deemed unsafe for fishing or swimming. Congress took strong action—passing the Clean Water Act over the veto of President Nixon—to enact a law regulating the pollution of U.S. waters. Over its first four decades, the Clean Water Act was one of the nation’s most effective environmental laws, significantly decreasing pollutant discharges by industry and reducing the rate of wetlands loss.

Yet in the early 21st century, a third of U.S. waters were still not safe for fishing and swimming, and wetlands were still being lost. In 2015 the Obama Administration finalized the Waters of the U.S. rule to strengthen Clean Water Act protections for the feeder sources (wetlands, ephemeral waters, and streams) that are important to healthy bodies of water.

In September 2019, the Administration repealed the Waters of the U.S. rule. In early 2020 the Administration released its replacement Navigable Waters Protection Rule, which stripped Clean Water Act protections for more than half of wetlands and a fifth of streams nationwide.

Analysis

“The Administration’s new rule conflicts with the best-available science on aquatic ecosystems,” says Rodewald, “and the impacts stand to be devastating.” Under previous Administrations, Rodewald chaired a panel of the EPA Science Advisory Board that reviewed the science underlying Clean Water Act protections, including a report that synthesized more than 1,200 peer-reviewed studies. The science, Rodewald says, clearly demonstrates the importance of protecting many types of water bodies, including isolated wetlands and ephemeral waters that flow from rain and snowmelt. She says the Administration’s rollbacks will degrade important bird habitat, increase flood risks, and damage water quality due to increased pollutants and runoff.

Limiting the National Environmental Policy Act (July 2020)

The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 has been called an “environmental Bill of Rights” by The Wilderness Society because it requires public participation in the review of proposed projects by federal agencies, as well as the consideration of less environmentally damaging alternatives. The idea to conduct comprehensive environmental reviews of federal projects came out of a series of Senate hearings about Florida’s Everglades in the 1960s that revealed a government working at cross-purposes; while the Interior Department was seeking more land protections, the Army Corps of Engineers was planning dams and canals to drain water out of the Everglades.

NEPA declares a national policy that requires an environmental review of all federal projects and a public-comment period so that citizens have a voice in the process.

In July 2020, the Administration introduced a rule to limit environmental studies and public comments under NEPA. The proposed rule also allows agencies to designate more projects that do not require environmental assessments.

Analysis

“NEPA provides a critical mechanism to safeguard healthy environments,” says Rodewald. “Without a strong NEPA, ecosystems will be more vulnerable to harm from federal projects.” During her decade on the EPA Science Advisory Board, Rodewald saw firsthand how NEPA connects science, policy, and environmental protection. In many cases, NEPA reviews are instrumental in modifying federal projects to meet societal needs in ways that are less harmful to ecosystems, she says. But Rodewald warns that without a legal mandate to seriously consider environmental impacts, federal projects are more likely to damage bird habitats. “Erecting dams, building highways, even timber harvesting projects may be able to escape a thorough EIS,” she says. Just as important, Rodewald says marginalized communities could lose their voices in a limited public comment process, making them more vulnerable to negative impacts from federal projects.

Research and text by student editorial assistant Anil Oza and Gustave Axelson, with support from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Science Communication Fund. Artwork and design by Jillian Ditner. Reviews and input contributed by Lynn Scarlett, former deputy secretary of the interior under president George W. Bush; Jay Branegan, senior fellow at the Lugar Center, which was founded by former U.S. Senator Richard G. Lugar; and Ya-Wei Li, Director of Biodiversity at the Environmental Policy Innovation Center.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you