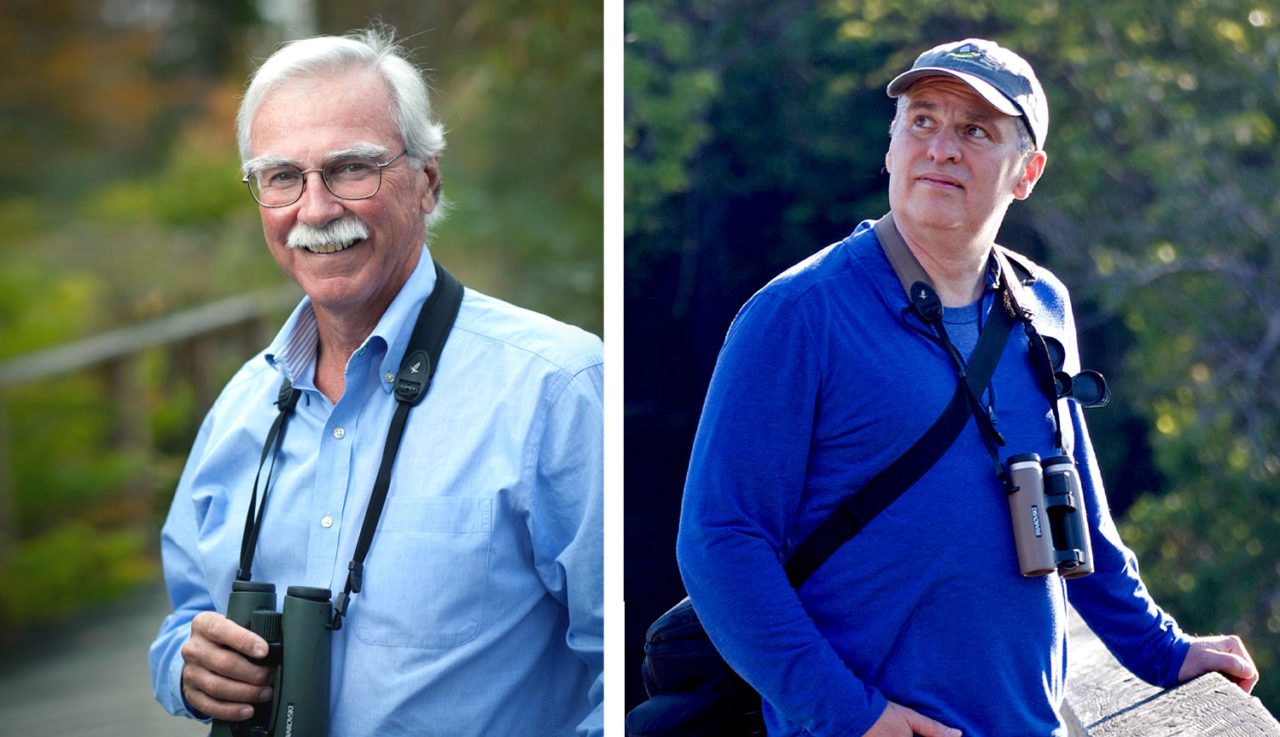

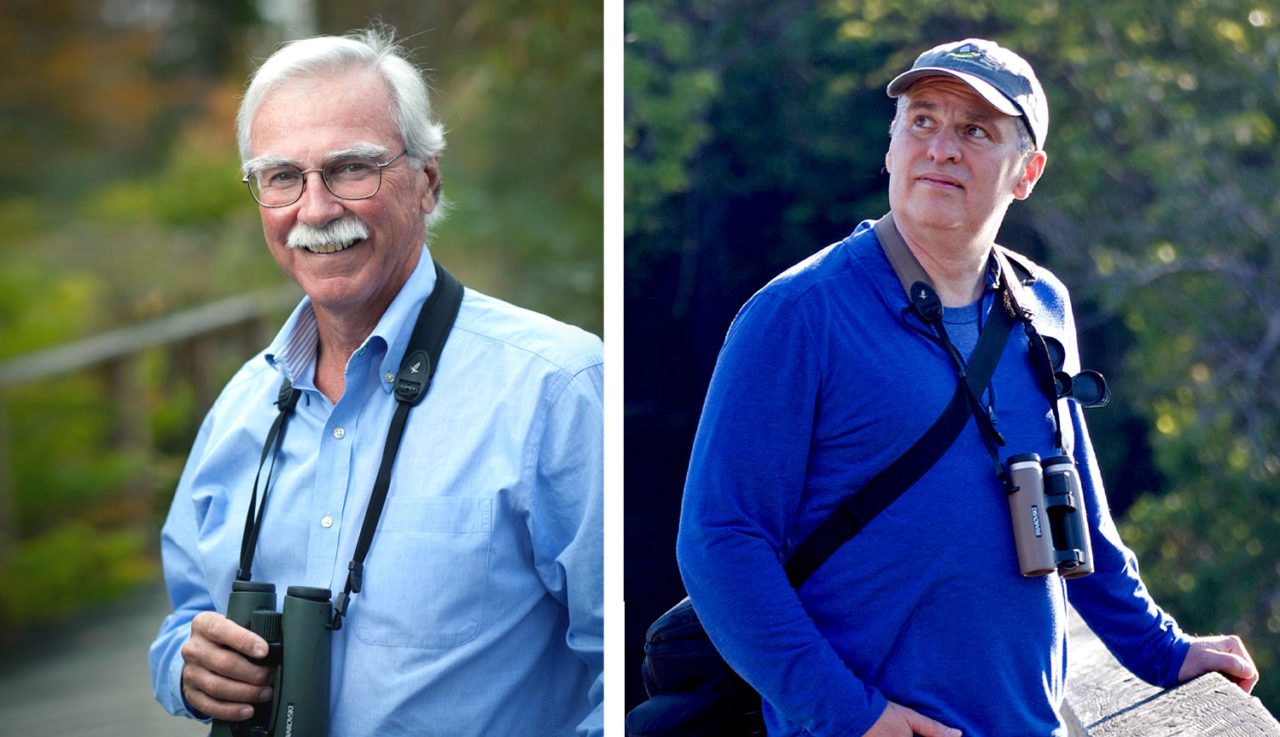

A Conversation with John Fitzpatrick and Ian Owens, the Lab’s Fifth and Sixth Directors

By Gustave Axelson

June 14, 2021

From the Summer 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

On July 1, 2021, John W. Fitzpatrick hands the reins of director at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology over to Ian Owens, who comes to Sapsucker Woods from the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. Living Bird editor Gus Axelson sat down with the outgoing fifth and incoming sixth directors in the 112-year history of the Cornell Lab for a conversation about the transition, the Lab’s future, and what it will take to bring birds back.

Q: Fitz, after everything you helped create at the Cornell Lab over the past two decades, I would imagine that you’ve got to feel like, in some respects, you’re handing over your baby to Ian.

Fitzpatrick: Honestly, I don’t regard the Lab as my baby. I regard it as one hell of a cool institution that we’ve been working to build. A lot of us. I’m certainly proud of what we’ve put together, absolutely. And, it meant a lot to me to make sure that we could find somebody very capable and very knowledgeable about birds, as well as about organizations, to take over as director. And we did that in Ian. So I couldn’t be more confident, nor more happy, about handing off the baton right now.

Q: So Ian, is there anything you’ve been saying to Fitz, any assurances you’re making to him, as you get ready to take the reins?

Owens: You’ve sometimes joked, Fitz, that leading the Lab is like holding a tiger by the tail. All the excitement. All of the danger that comes with that. And that’s what has struck me as I get to know the Lab. So I guess for me, probably the most important assurance as the new director is to keep carrying the flag for the kind of the idea that’s at the heart of the Lab. There’s a cultural part, the ambition. You’ve got to be ambitious. You can’t just say, ‘Let’s play it safe.’ You have to be entrepreneurial.

And then also the scope. The Lab was founded as this mixture between research and public outreach and conservation. As the wind blows in different directions, it’s pretty difficult to keep balance across those things. But there’s a special role in the director in holding that flag, knowing that direction, even when the wind is blowing in strange directions. I think it’s something that Fitz has done superbly well, growing all of those three things.

Q: Fitz, a couple of years ago, you spoke about what you said was one of the most important moments in the 100-year-plus history of the Lab, the publication of research in 2019 showing that North America has lost 3 billion birds in the last 50 years. I’m paraphrasing here, but you said there’s a new metric for the Lab going forward. If we’re doing our job, we’ll see that loss curve start to bend back upward. So how do we do that? How do we bring birds back?

Fitzpatrick: Bringing birds back is absolutely one of the flags that we have to have in front of us, that we have to be pursuing. It’s going to be absolutely impossible to do that by ourselves. It’s going to happen as a consequence of a bunch of organizations pitching in together, cooperating in the process, and also a change in the public attitudes. So we do work in the science arena, and in the public arena, to give it excitement and give it legs and give it momentum. Give it purpose, so that people begin to capture it themselves and start voting about it.

Because it’s going to be people that save birds. It’s not birds that save the birds.

Related Articles

Owens: I think that one of the things that we’ll see in the future is we are consciously trying to build a movement for birds. We have to avoid making it people against nature. So instead of talking about how to lock out all the people, lock out all the businesses, we have to make it so we’re trying to get to a sustainable future, for human activities and for nature.

Some of what we do at the moment is trying to make people aware of the scale and urgency of the crisis. That’s absolutely part of what we’re doing with the 3 billion birds lost. But we also need to show optimism. We need to share what works, or what could work. As conservationists, I think sometimes we can come across as we’re trying to get rid of everything except the nature. We have to change that narrative, so that it’s hopeful and optimistic. Because we have to bend that curve.

And it’s not just one silver bullet. It’s a combination. It’s changing gas emissions. It’s replanting trees…

Fitzpatrick:It’s almost certainly going to include changing insecticide habits. On the global scale.

Owens: Yeah. Big changes to agriculture. But again, I think our point is we’re not against agriculture. We see it as a key part of the environment. But we need to push towards a sustainable agriculture. For the industry. And for the birds, and the broader society.

Q: So how do we do that? How do we rally birders, and then build that out to the broader public, to bring birds back?

Owens: I’m very much a ‘think global, act local’ person. I think it’s going to be a lot of local actions. Some of that is for birders to share our enthusiasm and our vision with other people. Act on the land that you control, doing the right things there. Particularly around communal nature areas, think about them as an important part of our neighborhood. We’re not going to do it as individuals, we do it as a community.

I think we also have enormous power as consumers about how agriculture behaves. So I think we also need to be making smart choices. Bird-friendly coffees are a great example of that. The link between the coffee plantations and the birds that you see on migration. Again, we’re not against business. But we want sustainable businesses. As consumers, we have a lot of power.

Fitzpatrick: I totally agree with those points. I think one of the things that speaks to this local point that Ian has made is eBird. Our data analyst group has been able to look at extremely fine-scale, locally tailored studies of bird population trends that will allow us to start telling stories at very local scales.

Owens: That’s a really magic formula, science and storytelling. With so much urgency about taking action, sometimes people ask, ‘Do we need science anymore? Do we really need any more data to know what the problem is?’

But we need more science about why that is happening precisely, and what it’s going to take to turn that around. If we know some biology that is affecting the birth rates and death rates of these species, we then can begin to actually affect the birth rate or affect the death rates, whether it’s the juveniles or the adults.

I think our big opportunity is to couple public storytelling with scientific discoveries, so that we move those things out into the public discourse and find what resonates with the public as well.

Q: We talked about the decline, and we’ve talked about trying to rally people to bring birds back. But what makes you personally feel hopeful about the future for birds?

Fitzpatrick: I draw hope from the fact that birds are fundamentally resilient organisms. They do respond to management alterations. And there are lots of examples. Gus, we tell them a lot in this magazine. I mean the recent announcement that Bald Eagles are now, what, 10 times more common than they were 20 years ago? What birds tell us is that they will respond if we do our jobs right.

Owens: The environmental awareness amongst younger generations is my biggest hope. If I look back at myself in those days, you know I was a hardcore birder, but I didn’t have much broader environmental awareness.

I’ve got two boys in their 20s, and you can have a debate with them about global-level environmental issues, what the causes are, and what society needs to do. They have made personal choices about their diet and things like that. They are way ahead of my generation.

At the same time, I guess COVID has really emphasized that as well. You can already feel this building momentum towards appreciating nature, and particularly birds. When people come out of COVID lockdown, I think that appreciation for the local park, and for the cardinal singing, I don’t think that will go away. I think that will last.

Fitzpatrick: I’m going to mention one other thing that that has definitely become a source of optimism. The increasing capacity that we have to use technology to teach people in cool ways that they’ve never thought about before. The fact that there’s millions of people now who have this amazing little app called Merlin. Technology is allowing people to enjoy birds to a much greater degree, in every age class. So that’s pretty cool and that certainly gives us some hope.

Q: Well speaking of technology, we sourced a few questions from social media for you guys. There was a Twitter follower who read the piece about Ian in the spring Living Bird, in which he talked about Eurasian Marsh-Harrier as his spark bird to becoming a birder. They asked, Ian, if you had a spark bird for your career as a scientist?

Owens: For me, it would actually be a Sulphur-crested Cockatoo. When I was 26, I moved to Australia, first faculty job, and got a house near a park. Had two children. So we’d be out walking around with the kids early in the morning. And there was a playground we used to go to that had some huge eucalyptus trees. A local bunch of cockatoos used to do a kind of rain dance there, where they hang underneath the branch with their crest up, wings flapping, going “Raa-raa-raa!” displaying to each other. If you’ve got a couple of kids crying and you want them to stop? This was just an astounding thing to see.

And it couldn’t help but make you think, “What the heck is that about?” So I started thinking about these long-lived, incredibly social birds, these extraordinary displays, and the effects of deep evolutionary divergence. I started getting more interested in lineages, as well as individual species. So it was a very stimulating playground.

Q: One more question for both of you from a Facebook follower. Where’s your joy in birding?

Owens: That one’s easy for me. Coming to America at 55 years of age and discovering a new avifauna. Every day is just fantastic. On the way to the store I can kind of see a phoebe in a different way. The last couple of years, it’s been a renaissance for me, completely.

Fitzpatrick: That’s such a wonderful thing to hear. I’ll just say, Gus, my joy in birding is every single day. If I get to write a book someday, it’s going to be entitled, “The Woods Is My Church, and I Go Every Day.” I’ve known Ithaca for 26 years and I love birding there. I love finding out what’s going on today. Still trying to get that 200th species in my eBird yard list, but I’m up to 191 right now.

Owens: It never stops, does it? I can sit and watch a starling singing. It’s almost medicine. When you’ve got a busy job and you’re being pulled in lots of directions, birding gets you back in the zone, every single time. It’s no different for me than it was 35, 40 years ago. Same buzz.

Q: OK, last questions for you two. First Fitz. On July 1, your first day of semi-retirement, what do you do?

Fitzpatrick: I look at a calendar with no Zoom meetings on it. No more four and five Zoom meetings back-to-back!

Q: And Ian? Assuming employees are allowed back into Sapsucker Woods, back into the building this summer. What’s the first thing you plan to do on day one?

Owens: To be truthful, I have thought about Sapsucker Woods, one way or another, since I was a teenager. So I’d like to promise some sort of lofty activity. But I know I will walk over to the windows, pick up my binoculars, and look out over the woods.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you