Birds Need Clean Air Safeguards Just as Much as We Do. Here’s Why

By Ariel Wittenberg

Smokestack by darksoul72/Shutterstock. June 25, 2021Emerging research shows that birds provide another powerful reason for regulating air pollution.

From the Summer 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

For decades, songbirds were used to signal hazardous air.

Caged canaries brought deep underground into coal mines served as living, breathing carbon monoxide detectors for workers throughout the last century. Still today, the mention of “canaries in the coal mine” connotes a warning of imminent danger to humans.

But the reverse of that maxim is rarely considered: How does bad air that harms human health affect birds?

Two years ago, a landmark study published in the journal Science documented a staggering decline in North American breeding bird populations—nearly 3 billion birds lost since 1970. The declines occurred among birds in every biome, with more than 300 species suffering population losses. But the study did not examine what caused the declines. Lead author Ken Rosenberg, a conservation scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, said he and his coauthors figured the bird losses were driven by a number of overlapping causes, habitat loss chief among them.

Then he attended a Zoom presentation at the virtual North American Ornithological Conference last summer about increasing mercury levels in blood samples from birds, and he began to wonder: What role might air pollution have played in the bird declines?

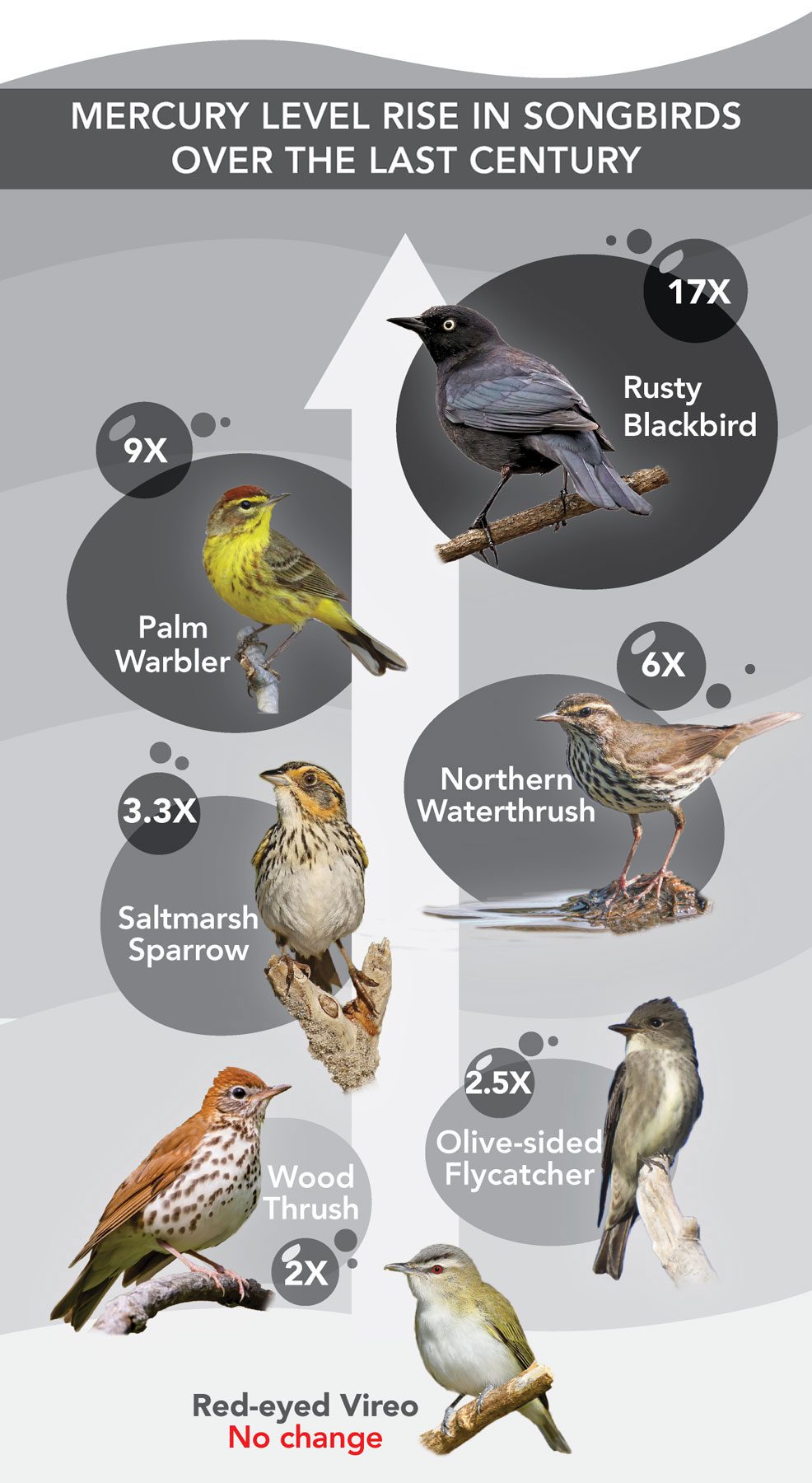

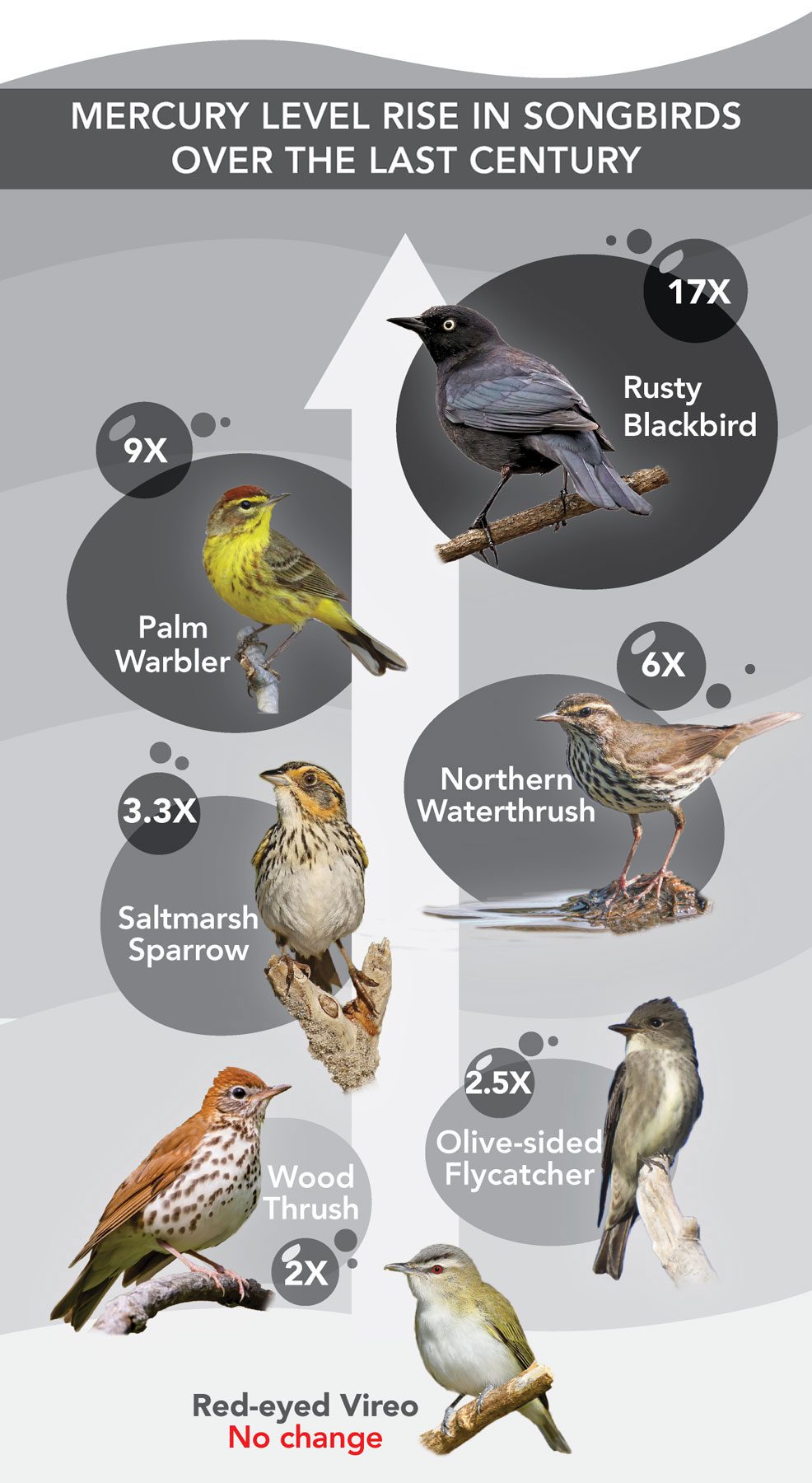

That presentation by Marie Perkins, assistant professor of wildlife ecology at University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point, described her research examining mercury levels in songbird feathers from seven species. She found that mercury increased over time in six of the seven bird species she studied, with samples collected after 2000 showing two to 17 times more mercury than historic samples. Air pollution was “the major source” of mercury contamination, according to Perkins. The greatest increase was in the Rusty Blackbird, a species that has declined by 90% since the 1960s.

But it was the Red-eyed Vireo that caught Rosenberg’s attention, as the lone species in the study without increased mercury levels.

“That happens to be one of the few songbirds in our big study whose population is increasing, not declining,” he said. “That did make me think, ‘Wow, maybe there is some relationship to mercury and this overall decline.’”

Other recently published research draws a more direct link between air pollution and birds, showing how government regulations aimed at making air cleaner for humans helped birds, too.

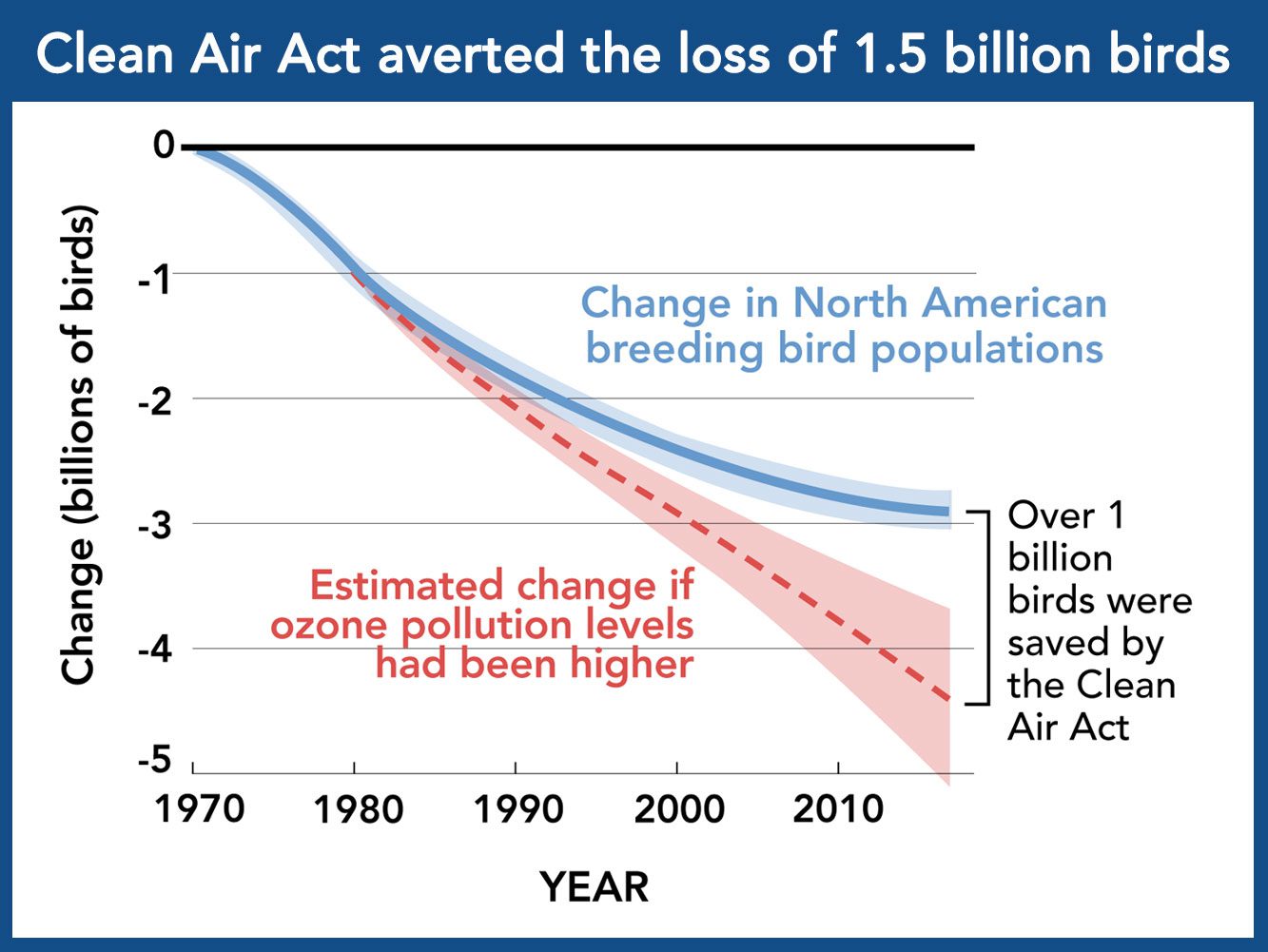

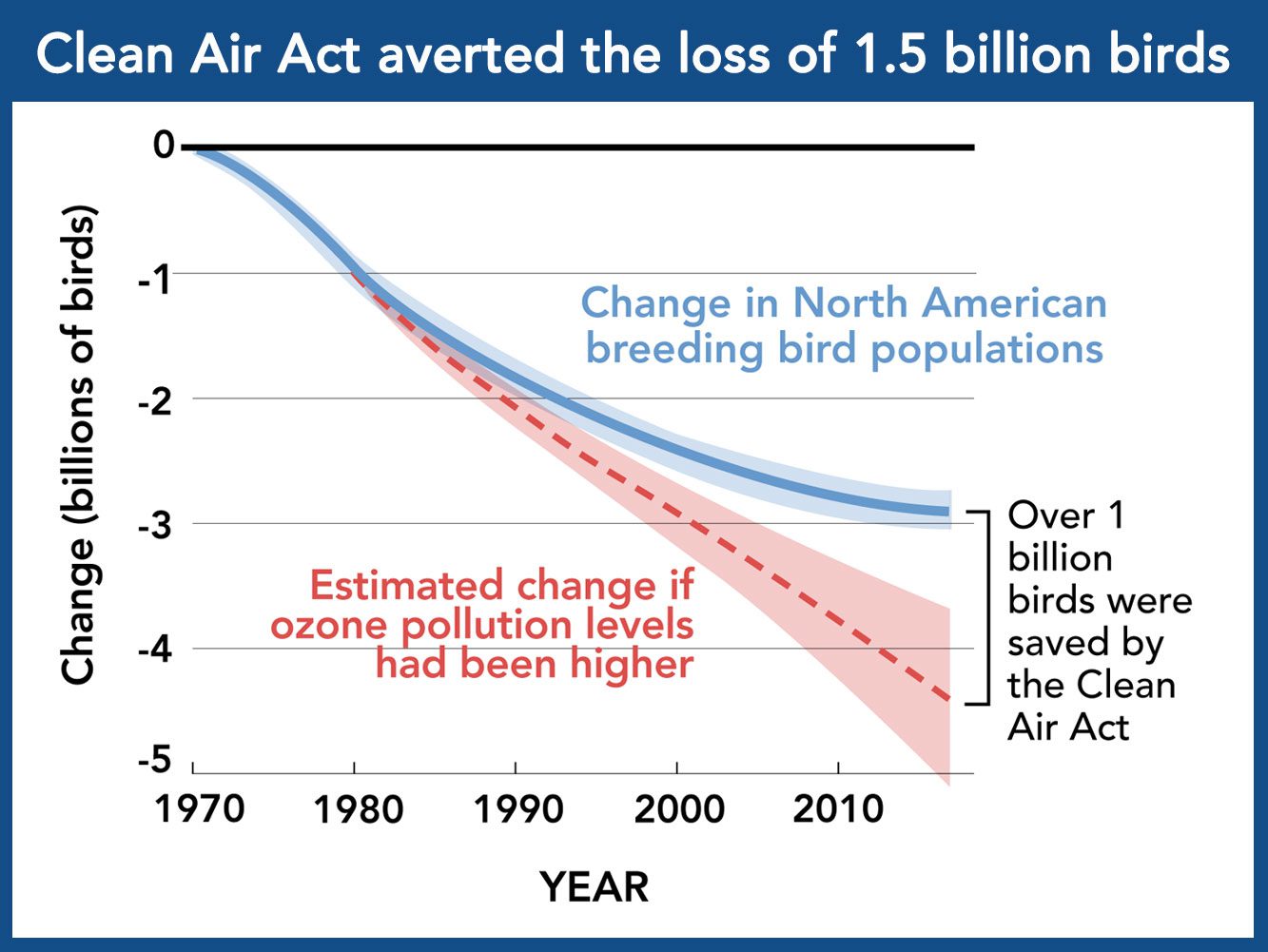

“The big take-home message is, what’s good for birds is good for people,” said Amanda Rodewald, senior director of the Center for Avian Population Studies at the Cornell Lab, and coauthor on a study published last December that showed the Clean Air Act helped save the lives of 1.5 billion birds.

According to Rodewald, the linkage between air pollution and birds is a ripe area of study that deserves more attention, especially because, with a new presidential administration, the time is right for gathering as much evidence as possible to support clean-air policy.

“We actually stand to gain multiple benefits—not only for human health, but for birds and conservation—when we control air pollution,” Rodewald said.

As a neurotoxin, mercury can harm the brain and nervous system. In humans, exposure to mercury has been linked to lower IQ and behavioral problems.

Mercury primarily gets into waterways by two methods: direct discharges of power-plant and factory wastewater to rivers and streams, and air emissions from power plants and mining operations. As for airborne mercury pollution, an estimated 2,220 metric tons of global annual air emissions are windswept across thousands of miles—even across oceans—before settling on rocks, soils, and surface waters. That means even seemingly isolated ecosystems without any nearby polluters can still have significant mercury contamination.

Once mercury gets into lakes and rivers, bacteria convert it to an even more toxic form—methylmercury—that is difficult for living organisms to process or get rid of. The methylmercury sticks to plankton, which are consumed by fish or insects, which are in turn eaten by progressively larger fish and insects, until finally they are eaten by humans or other animals. Each predator ingests not just its prey, but also any mercury that prey has consumed.

This biomagnification process of a neurotoxin is one reason pregnant women are warned against eating too many predator fish, like swordfish. Because fish are the largest source of mercury in human diets, much of the early research into bird exposure to mercury has been similarly focused on piscivores, or fish-eating birds. Studies have shown that loons with high mercury levels may not incubate their eggs properly.

“For the past several decades, this has always been considered a fish thing,” said David Evers, codirector for mercury studies at the Biodiversity Research Institute.

Evers got his start researching mercury in loons. But he “had a discovery” 20 years ago while conducting an environmental assessment at a Massachusetts Superfund site heavily contaminated with mercury. His team had been tasked with catching Belted Kingfishers at the site to test their blood, the thought being piscivore kingfishers would be a good indicator of mercury pollution in the environment. But when the mist nets accidentally caught a number of Red-winged Blackbirds, Evers’s team decided to sample their blood, too.

“The blackbird mercury levels were five to 10 times higher than the fish-eaters,” he said.

Since then, Evers’s research has found that mercury can impact insect-eating birds just as much, if not more, than piscivores. Songbirds eat insects that have previously ingested the compound, and because they generally have smaller bodies and higher metabolisms than fish-eating birds, songbirds tend to eat more food relative to their body weight.

Last fall, Evers was editor of an issue of Ecotoxicology devoted to mercury and birds. The special issue published 15 new studies, including Perkins’s, which together found that at least 58 migratory songbird species have demonstrated effects from mercury. The negative impacts include navigation, flight, and endurance, all of which, in turn, could be harming birds’ reproductive success.

Biomagnification in action: Carolina Wrens often eat spiders. Because spiders are themselves predators, they can contain relatively high levels of mercury which they pass along to the wrens that eat them. Photo by Ron Reuter.

Aquatic songbirds like Saltmarsh Sparrows are also prone to having high levels of mercury in their blood, because mercury is converted to more dangerous methylmercury in the water. Photo by Evan Lipton/Macaulay Library.

“I am convinced that mercury has population-level impacts on many bird species, not just in North America, but around the world,” Evers said.

One such species is the Carolina Wren, with one study finding that mercury impacts every aspect of their reproduction—from the number of eggs laid, to the mother’s ability to properly incubate, to the number of eggs hatched, to chicks’ success fledging from the nest. The food chain is to blame, specifically the link that Carolina Wrens typically eat a lot of spiders.

“Spiders eat spiders, spiders eat dragonflies, which eat other bugs,” Evers said. “Any time you eat a spider, you are eating all the mercury that was eaten by everything the spider ate. The mercury biomagnifies up the food chain.”

Wetland songbirds that eat aquatic bugs are also more at risk because mercury is converted to methylmercury in water. Fluctuating water levels can accelerate that conversion process, so birds living in tidal areas can be more exposed. A study at a single Maine wetland found that two declining wetland species—Saltmarsh and Nelson’s Sparrows—have high levels of mercury in their blood.

Saltmarsh Sparrows are a species in steep decline, with a 75% population loss since the 1990s. Rising sea levels and nest flooding have been implicated as a prime cause of their declines. But the Maine study showed another possible driver, as Saltmarsh Sparrows had higher mercury levels in their blood than Nelson’s Sparrows.

Evers said he thinks mercury could be a major driver in the declines, noting that Saltmarsh Sparrows also tend to eat bigger spiders than Nelson’s Sparrows.

Red-eyed Vireos are another species that could provide a clue to the link between mercury and birds. As an upland species, Red-eyed Vireos generally don’t forage in wet areas where mercury might be converted to methylmercury. That could explain why the vireo samples in Perkins’s analysis didn’t show increasing mercury levels, and perhaps, why the bird’s population is not declining.

“They could be eating more plants and fewer insects, and they could be just foraging in areas where mercury is not in the food chain,” she explained.

Olivia Sanderfoot, who works at the University of Washington’s Quantitative Ecology Lab, has spent a lot of time reviewing the available research on how air pollution impacts birds. Studies dating back to the 1960s have linked different pollutants in the air to birds’ respiratory illness, immunosuppression, and declines in breeding, she said.

“It is not surprising to me that if the air pollution we have been exposed to in the past 40 years has made people sick, it would make birds sick or affect them in a way that ultimately influences the number of birds in this country,” she said.

Many studies looking at air pollution in birds, including those published in Ecotoxicology’s special issue on mercury, focus on localized populations of specific species. There’s only limited research, Sanderfoot said, on how emissions might impact birds on a continental scale. But that’s starting to change.

Last December, researchers at Cornell University published a study showing 1.5 billion birds across North America may have been saved since 1970 thanks to government regulations aimed at preventing the creation of harmful ozone.

There are two types of ozone. Naturally occurring ozone in earth’s upper atmosphere is largely considered good for people and animals because it protects us from the sun’s ultraviolet rays. But ozone that forms at ground level is the main ingredient in smog and can worsen lung diseases like emphysema and asthma. Ground-level ozone is not natural and is created by chemical reactions between two air pollutants, nitrogen oxide and volatile organic compounds. Both are emitted by power plants, cars, and factories, and react with each other to create ozone when temperatures rise. In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency works to prevent ground-level ozone by regulating nitrogen oxide emissions. EPA data shows a 25% national reduction in ozone concentrations between 1990 and 2019, thanks largely to government regulations under the Clean Air Act.

The Cornell study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used computer models to combine bird observations logged in the Cornell Lab’s eBird program with ground-level pollution data for more than 3,000 U.S. counties over 15 years. The study tracked monthly changes in bird abundance via eBird and changes in air quality via the NOx (nitrogen oxide) Budget Trading Program implemented by the EPA. The study revealed that regulations that reduced nitrogen oxide levels helped preserve bird populations, saving the lives of 1.5 billion birds.

The findings also revealed that ground-level ozone is most harmful to small migratory birds like sparrows, warblers, and finches, which make up 86% of all North American landbird species. Rodewald, one of the Cornell Lab scientists who was a coauthor of the study, said that ozone pollution is likely to impact the respiratory systems of birds, much like it does in humans. But, she said, birds have a unique way of breathing that could make ozone’s impacts even more powerful.

Bird lungs use a system of air sacs that allow them to constantly inhale fresh air, even as they push air out. That’s different from humans, who take separate actions to inhale and exhale. Birds’ continual inhalation is necessary to obtain the oxygen necessary for long flights and migration, but it also means they could be more at risk from air pollution.

“There is a continuous air exchange, which means that their exposure would be much greater than a mammal of comparable size that breathes in and out separately,” Rodewald explained. Birds with lungs damaged by ozone may struggle to migrate or be less fit when they arrive at their breeding destinations, and therefore less attractive to prospective mates. Ozone can also damage vegetation, which in turn can impact food and nesting resources, creating an additional, indirect effect on birds.

“The declines we see in birds from ozone make sense given what we know about how ozone impacts birds and plants,” Rodewald said. She hopes the research looking at air pollution’s impact on birds can be used to inform conservation decisions.

That’s already happening at Kelly Slough National Wildlife Refuge in eastern North Dakota, thanks to a decade of research by Virginia Winder, a biology professor at Benedictine College. She stumbled upon high mercury levels at the refuge when conducting research for her doctorate, which focused on mercury concentrations in Nelson’s Sparrows.

After discovering that sparrows in North Dakota’s Red River Valley had higher mercury levels than sparrows elsewhere, Winder visited the refuge to investigate. She found a hotspot of pollution, with sparrows breeding there containing four to five times more mercury in their blood than those breeding at sites in Ontario, Canada, and elsewhere in North Dakota.

Read More

“I had no idea I’d be stumbling into the mercury exposure levels that I did,” Winder recalled. She published her findings in a paper that eventually caught the eye of refuge wildlife biologist Mark Fisher, who wondered whether the refuge’s water-management regime could be playing a role.

Located a few miles northwest of Grand Forks, North Dakota, Kelly Slough refuge contains thousands of acres of wetlands crossed by a stream. Since the 1990s, refuge staff had plugged that stream during the spring, summer, and fall to create pools as breeding habitat for sparrows and waterfowl. The pools would hold up to two meters of water for months at a time.

“But nobody ever thought about what the levels of mercury were going to be like, and could we be causing a spike in methylmercury—that was not on anybody’s radar screen,” Fisher said. Of course, refuge staff weren’t entirely to blame: No one was directly depositing mercury into the refuge or just upstream of it. Rather, mercury was traveling there in the atmosphere from faraway smokestacks. But the refuge’s water management regime was creating optimal conditions (stagnant pools) for the anaerobic bacteria that convert mercury into the more toxic methylmercury.

Refuge staff were horrified by Winder’s research. They decided to see whether allowing more water to flow through the system would help prevent the mercury falling from the sky from becoming methylated in the standing water of dammed-up pools.

“We did not want to be providing poisoned habitat,” Fisher said.

The experiment worked, and in 2017 the refuge permanently changed its water-management schedule. Now, staff only plug the stream long enough to create shallow pools of water six to 12 inches deep, which sit for only a few weeks before flowing out. The practice has considerably reduced methylmercury levels in the wetlands—and mercury levels in birds’ blood.

Winder’s most recent study found samples from songbirds and ducks living in wetlands with free-flowing water had 67% and 49% lower mercury concentrations, respectively, than birds in wetlands where water flow was restricted. The findings are a welcome change for Fisher.

“It’s like I’ve always been a jet fighter pilot, but I used to just fly the plane and now I actually know how the plane works,” he said. “Now I understand the function of the wetland.”

Unfortunately, mercury pollution in birds isn’t always so easy.

Allyson Jackson, an assistant professor of environmental studies at Purchase College, SUNY, has been researching how songbirds at Acadia National Park in Maine could be exposed to mercury through their food.

“It’s hard for the park because they do everything they can within their borders to keep mercury out, but they can’t stop it from coming in through the air,” she said.

Jackson has been looking at mercury levels in emerging aquatic insects like mayflies and stoneflies in different wetlands and streams throughout the national park, some of which are “degraded.” Though she has not yet published her research, Jackson believes differences in insect habitat quality could be influencing songbirds’ mercury exposure.

“There is a relationship between how good an environment is at producing emerging aquatic insects and how many get out of the water for birds to eat, which in turn impacts their mercury exposure,” she said. In other words, the wetland habitat at Acadia that’s great at producing lots of insects for birds to eat could, in turn, be leading to higher levels of mercury poisoning in birds.

Such findings would present a tricky dilemma, because wetlands that produce a lot of emergent insects are typically considered healthy habitats. As Jackson put it: “You can’t tell people, ‘Well, what you want is a body of water that doesn’t produce emerging insects’—that’s crazy.”

Instead, she hopes her work could provide “ammunition” to policymakers looking to regulate and limit mercury pollution: “The more information we can produce, the better we can explain why we should stop coal-fired power plants and stop emissions from our country and others, because once it’s out there, you can’t control where it goes or how it affects the environment.”

Rodewald, the Cornell Lab coauthor of the study that linked the Clean Air Act to saving a billion birds, likewise said she hopes her research supports a “more holistic approach to conservation.” She likened emerging research on air pollution and birds to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which 60 years ago investigated the harms pesticides like DDT were wreaking on birds and insects. The book helped jumpstart the national environmental movement that culminated in the creation of the EPA.

However, once the EPA banned DDT, Rodewald said, wildlife conservation paid less attention to pollution.

“The impact of pollutants hasn’t received as much attention until recently,” she said. “But [conservation] isn’t only about protecting habitat, it’s also about making sure we have the regulations and policies to keep those habitats clean.”

Policy watchers say they believe President Biden’s EPA will strengthen standards for air pollution. In particular, they cite remarks the president has made emphasizing the importance of addressing the outsized amounts of pollution seen in low-income communities and communities of color.

“Environmental justice will be at the center of all we do addressing the disproportionate health and environmental and economic impacts on communities of color,” President Biden said in January while signing an executive order on climate policies.

That could mean tighter restrictions specifically on nitrogen oxide, because ground-level ozone can cause significant respiratory health problems that are already prevalent in “environmental justice communities,” said Paul Billings, senior vice president for advocacy at the American Lung Association. Currently, power plants and factories are allowed to emit 70 parts per billion of nitrogen oxide over eight hours. The standard was first set by the Obama administration in 2015, but a federal court directed the EPA to review those levels after the agency was sued by environmental health groups, including the American Lung Association, arguing for stricter standards. The Trump administration ignored those concerns and finalized a new regulation maintaining the 70 parts per billion nitrogen oxide level last December.

While public health groups are now pressuring the Biden administration to lower the nitrogen oxide standards, the EPA was sued in February 2021 by a different kind of group—the Center for Biological Diversity. The Center argues the EPA should have consulted with the Fish and Wildlife Service about how air-pollution standards would impact endangered species like Whooping Cranes.

The Biden administration is also under pressure to strengthen mercury-pollution standards. At issue is a determination that mercury is, indeed, a hazardous air pollutant—a finding first issued by the Clinton administration, then used by the Obama EPA to set the first-ever limits on mercury emissions. EPA data shows those regulations are working, with emissions from power plants dropping by 19 tons annually between 2014 and 2017.

But under President Trump, the EPA withdrew the designation of mercury as an air-pollution hazard, prompting a coal-industry lawsuit arguing that mercury pollution could not be regulated if it was not considered hazardous.

“The Trump administration essentially gave the coal industry reason to sue,” explained Ellen Kurlansky, a former EPA policy analyst who worked on the mercury standards.

On President Biden’s first day in office, he signed an executive order directing federal agencies to review a slew of actions taken by the Trump administration that roll back public-health regulations, including Trump’s de-designation of mercury as an air pollutant. EPA spokeswoman Enesta Jones wrote in an email that, per President Biden’s executive orders, the agency is “reviewing recent air regulations to ensure that they protect public health and the environment.”

“I am optimistic about the words the president has said,” said the American Lung Association’s Billings. “Now comes the hard work where EPA and the rest of the administration has to make that vision a reality.”

Direct regulations on mercury and nitrogen oxide pollution aren’t the only means of curbing air pollutants and helping birds. For example, the Biden administration has also vowed to reinstate fuel economy standards for cars that will require automakers to manufacture cars that can travel farther on less fuel, which would ultimately reduce vehicles’ nitrogen oxide emissions as well. And, Biden’s Earth Day pledge to halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 would likely result in coal power plants shuttering sooner, reducing mercury emissions.

“That’s the nice thing about climate policy, it indirectly ends up being health policy, too,” said Ivan Rudik, a Cornell University economist who worked with Rodewald on the Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences study. “Almost anything they do to combat climate change, whether it’s incentivizing solar and wind power, or electrifying cars, all of that is going to reduce ozone.”

Similarly, the administration’s vows to work with international partners to stem climate change could have indirect impacts on reducing airborne mercury pollution from abroad that reaches the U.S. Developing countries like China and India still heavily rely on coal-fired power plants, and mercury emitted in those countries can travel in the atmosphere and settle on the ground and in waterways in North America.

According to Olivia Sanderfoot, the University of Washington quantitative ecologist, the multiple policy channels for making air cleaner will pay off in multiple ways for all living things.

“We know human health is impacted by these pollutants, so it’s going to be a double win if we can increase air quality because we will improve it for all air-breathing animals,” Sanderfoot said.s

“The same policies that make us safer keep birds safer, too.”

Ariel Wittenberg is the public health reporter at E&E News, an energy and environment news service based in Washington, D.C.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you