A Miracle of Abundance as 20,000 Whimbrel Take Refuge on a Tiny Island

Story by Scott Weidensaul; Photos by Andy Johnson

Whimbrels. pelicans, and more take to the sky at Deveaux Bank, South Carolina. October 13, 2021Vast flocks of Whimbrels were thought to be a thing of the past, until a wildlife biologist discovered nearly 20,000 of these declining shorebirds on a tiny South Carolina island.

From the Autumn 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

I am waiting on a sandy island along the South Carolina coast, on a late evening in May when the low light has gilded everything around me—the waving cordgrass where Marsh Wrens sing, the beach where plovers and sandpipers scurry, the flocks of Black Skimmers that row by with mothlike wingbeats and peevish calls. I have been told that if I wait here for dark, I will see a miracle…a word I use with careful deliberation.

With dusk, the miracle arrives.

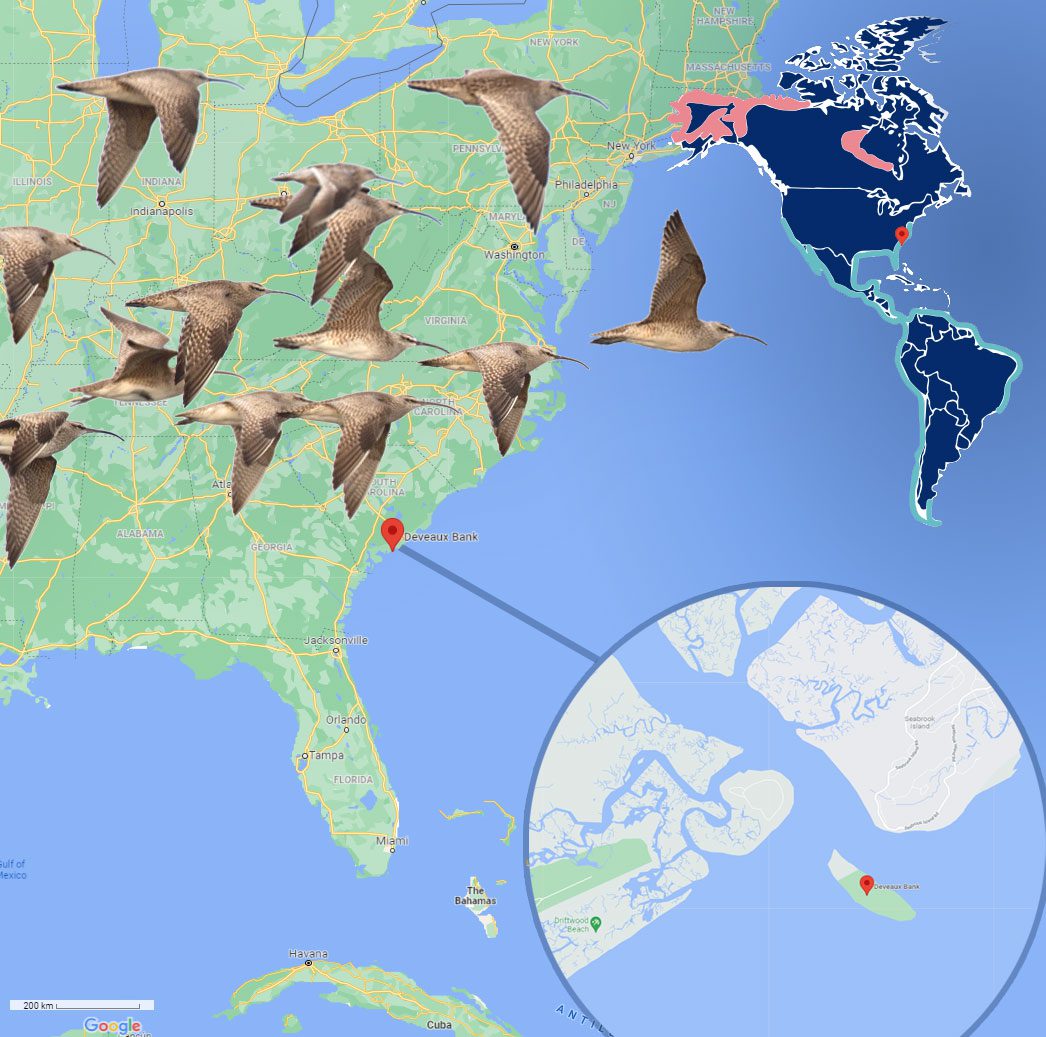

Flocks of Whimbrels appear, a few dozen at first, then by low hundreds, then in such numbers that I have a hard time keeping any sort of count. Drawn shoreward from the distant, marshy horizons, they fly in ragged lines and loose clusters, untidy chevrons of big, strong shorebirds, nut-brown bodies and long, flashing wings, beaks curved like the crescent moon that will appear in the black sky a few hours later. A few circle, calling, but most land without preamble on a wide, flat expanse of overwash beach on the edge of the island, facing into the wind in dense-packed ranks. More, and more, and still more.

SANDERS: Deveaux Bank is a large sandbar. It’s actually shaped like a horseshoe. In the interior are broad marshes and some dunes, some grasses, some low shrubs. It has wide, fairly exposed beaches. A couple years ago I was anchoring the boat on the back side and I just happened to be there right at dawn. I could just hear swirls of birds passing over my head. Thousands of Whimbrel came off the island. I was just amazed and I thought: “how had I never seen this before?” I realized it needed further investigation and documentation.

SANDERS: A Whimbrel is a type of curlew. It has a long decurved bill for probing in the sand for crabs and invertebrates, and it’s a long-distance migrant.

DR. NATHAN SENNER, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA :They are spending six, seven months of the year down on the northern coast of South America, and then they’re making this jump up to the Atlantic coast of the U.S. From there, they’re making flights up to their Arctic breeding grounds. We’re talking days, sometimes even a week, without stopping, without food, without sleep. What that means though is that the places that they do choose to stop are really critically important.

SANDERS: On the northern migration a lot of the whimbrels stop in South Carolina for a month, a month and a half. That whole system of marshes and undeveloped coastline is critical to the survival of this species. They spread out all across the coast throughout the day to forage in the mudflats and then they come together to spend the night. And in South Carolina, that’s at Deveaux Bank.

SANDERS: It’s May 16th, and it’s pretty close to a full moon so the tides are extreme and the Whimbrel will be concentrated at a few spots, so it’s a really great time to count them.

MAINA HANDMAKER, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA: So Abby’s stationed at the southwest point of Deveaux kind of on the sand spit, the very tip. We’re kind of right in the middle looking for the birds coming mostly from northeast. Here comes our first big group, maybe about 80 just came in.

DR. STERLING: These birds could theoretically be coming in from a tremendous distance away. As the tide rises and night falls, they’re leaving those foraging areas where they’ve been eating all day and coming out to these areas that are a little bit more remote where they’re safe from predators.That was another 40 that just came in.

DR. SENNER: Curlews worldwide are a group of birds that we know is prone to extinction, and whimbrel are among those.

DR. STERLING: So this group here is like 180 flying over us right now.

DR. SENNER: Somewhere around 40,000 Whimbrel use the Atlantic flyway of North America.

DR. STERLING: Hundreds and hundreds of Whimbrels over the marsh.

DR. SENNER: That population already represents a decline of about half from where they were 20 years ago.

DR. STERLING: By now there’s literally thousands of birds all around us. It’s the craziest thing I’ve ever seen. 207…We won’t be able to count them much longer because it’s just too hard to see them but you can hear them calling still as they’re coming in. There’s another group, and another group. Oh my gosh, the entire the entire point all the way to those signs is covered in birds now.

DR. SANDERS: We were all tallying our numbers and it took quite a while to go through our notes.

64. 175. I remember I wrote down the numbers from all the parties [DR. STERLING: 140…700…] And could not believe it. [DR. STERLING: 65…400…750…207.] [HANDMAKER: Holy Moly] [DR. STERLING: that’s a lot of birds…a lot of Whimbrel. SANDERS: Yeah. It was about 19,500 birds.

DR. SENNER: That blew my mind because that’s half—literally half of estimates of how many Whimbrel there are on the Atlantic coast. For all of them to be coming in to roost on this one tiny island that just…that blew my mind. We’ve never encountered this many Whimbrel in any one spot anywhere else in the world. That is unique. That means that Deveaux is a really special place.

SANDERS: A discovery of this size really seemed impossible. How could there be a half of the estimated population at one place and personally in my backyard in South Carolina.

CHIP CAMPSEN, SOUTH CAROLINA STATE SENATE: There are certain things that we should refuse to destroy and those things that we should refuse to destroy are those things that really define us, that make us unique, that bring us together. And in South Carolina, by preserving those places, we have refused to destroy the best part of us. We’ve created good habitat for Whimbrel to give them a chance and we just have a responsibility to do what we can to keep them from becoming extinct. Because we know that the future of that species is in our hands.

DR. SENNER: We know how the decline of Whimbrel potentially ends. We know how that story could end. But their population size is still large enough at this moment, that we have the time to do something before it’s too late.

SANDERS: Seeing thousands of Whimbrel come in to roost at night, it kind of just gives you hope that you know so many birds exist. It’s one of the most phenomenal sights I’ve ever seen in my life.

DR. J. DREW LANHAM, CLEMSON UNIVERSITY: I don’t think there is anybody that doesn’t love a beautiful thing. You don’t even have to know what they’re called, what the birds are, and you watch them come in on that sunset and you have to be amazed, you have to be astounded, and you have to be proud to know that that’s here.

TEXT ON SCREEN: Departure: 6:00 A.M.

End of Transcript

A little before eight o’clock, a huge flock sweeps toward me out of an orange sunset. They move in a wide sheet, high at first and then spilling toward the ground like water flowing down a low hill, bunching and veering en masse to their left, following the beach on which I stand. There are perhaps a thousand of them. Seven-whistle calls ring like old brass sleigh bells. They surge around me like river water parted by a rock; there is a moment of wild mayhem, the air churned by motion and wings, and they are gone.

Whimbrels have, to me, always been the big game of shorebirds—large, powerful, wary, usually in small and scattered numbers. Like all of the world’s seven remaining species of curlews, they are in serious decline. In my experience, a big flock is half a dozen or so; seeing 40 or 50 makes for a red-letter day. And when I do encounter a decent-sized flock, I can’t help but mourn the vanished legions of now-extinct Eskimo Curlews.

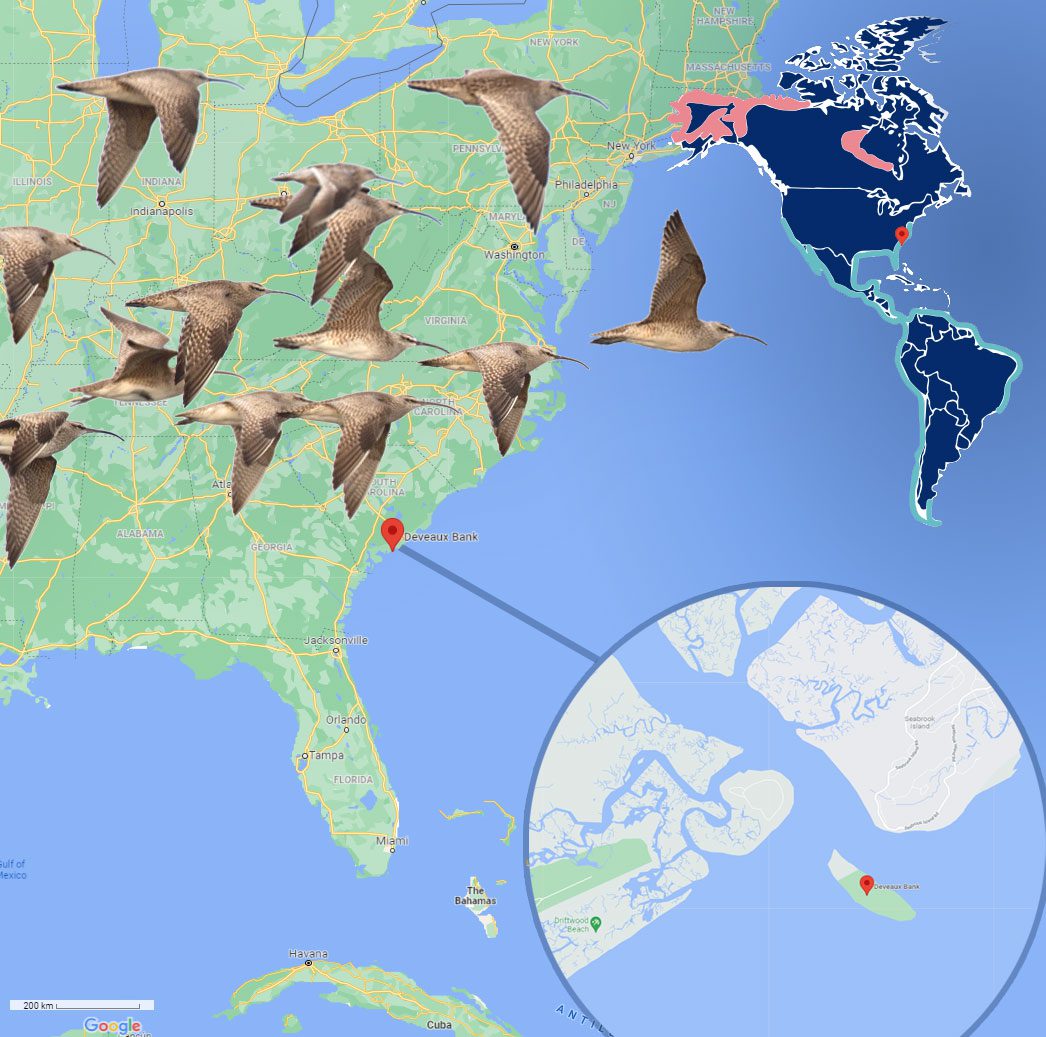

The Whimbrel spectacle I was experiencing on the coast of South Carolina in May 2021, on an ephemeral barrier island known as Deveaux Bank near Charleston, was something few people alive today have ever seen. Whimbrels congregate here for a month or more in spring, pausing in their migration between the coast of South America and the Canadian Arctic, to feed on fiddler crabs in the rich tidal marshes. Some 20,000 Whimbrels gather each night on Deveaux Bank during this migratory stopover, the largest such congregation known anywhere on the planet.

In this age of diminishment, when the rarest thing in nature today is sheer abundance, the Whimbrels of Deveaux seem like a glimpse of a vanished time when the continent surged with great shorebird flocks. This discovery, announced to much fanfare in June by a coalition of partners including the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is remarkably good news: a mother lode representing half of the Atlantic flyway population of Whimbrels and a quarter of all the Whimbrels in North America. That first night, I wept to see them—a reaction, I learned, which has been almost universal among those so privileged.

But think of those birds another way, and a panic may begin to rise. The discovery at Deveaux is a miracle, yes, but this is the eleventh hour for Whimbrels, a species that has declined by more than half since 1994 on a plummeting trend that shows no signs of reversing. The fact that so many birds gather on this one small island highlights a previously underappreciated facet of Whimbrel biology—and shorebird biology in general—that could reveal a key to any conservation strategy to save them: simply providing these birds a safe place to spend the night.

Deveaux Bank at sunrise with key points for the Whimbrels marked out. Tap or click through the slideshow for more details. Photo by Andy Johnson.

Foraging Travels. Deveaux Bank offers safe harbor at night, but Whimbrels must fly inland to marshes or river edges to find food. This area of coastal South Carolina serves as a migratory stopover complex of foraging and roosting areas. Photo (with Marbled Godwits) by Andy Johnson.

Prime Real Estate. Nearby Seabrook Island is a popular vacation spot that’s been heavily developed since the 1970s. But thanks to conservation efforts in South Carolina, Whimbrels can still find areas inland for foraging among some of the largest intact saltmarshes along the East Coast. Photo by Andy Johnson.

A Protected Cove. The inside rim of Deveaux Bank’s horseshoe offers a sheltered strip of marsh grasses and mudflats for shorebirds. Photo by Andy Johnson.

Whimbrels and More. Deveaux Bank is important habitat for more than 50 shorebird and seabird species, including one of the biggest Brown Pelican nesting colonies in the East. Photo by Andy Johnson.

Dunes Facing the Sea. On Deveaux Bank’s front beach, dunes of dry, high sand provide a barrier from the waves to protect the inland side of the island. Photo by Andy Johnson.

Devaux Bank is a giant horseshoe with its open end facing west, sitting in the mouth of the North Edisto River that nourishes it with sediment. Rimmed on three sides with sugar-sand beaches, the long fingers of cordgrass marsh all but bisect its middle. First noted on charts in the 1920s, it was used as a bombing range in World War II and then wiped out entirely by Hurricane David in 1979. Three years later it reemerged from the waves and began regrowing. Just how big it is today depends on the stage of the tide; figure 250 acres as a good average.

Long recognized as critical bird habitat, Deveaux Bank hosts nearly 3,000 nesting pairs of Brown Pelicans, as well as breeding Black Skimmers, American Oystercatchers, Royal and Sandwich Terns, Laughing Gulls, and several species of herons and egrets—the largest Atlantic Coast colonies for several of these birds. The island is a state bird sanctuary and designated Important Bird Area, with all but two small areas, mostly below the high tide line, closed to the public during the nesting season. It’s been a big part of Felicia Sanders’s professional life for more than 20 years.

Sanders, a lanky wildlife biologist with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources with sun-bleached hair and an easy smile, has worked on Deveaux Bank since 2001, monitoring the nesting seabirds as well as migrant shorebirds, including as many as 6,000 federally listed Red Knots. She’s intimately familiar with the marsh-rich coast near Charleston, with its seasons, its tides, and its rhythms. Yet for most of those years, she never suspected that Deveaux held another, blockbuster secret.

It started with an annoying mishap in the shallow, challenging waters around Deveaux.

“In 2014 I was taking some DNR videographers to film the pelican colony at dawn. So we got there in the dark, and we got the boat stuck on the back side of the island,” Sanders said. “I saw all these Whimbrel coming off the island, just thousands of them and thousands of other shorebirds, and I realized it was a nocturnal roost for a lot of migratory shorebirds.”

She filed away that surprising observation, too consumed with her other duties to pursue it, but a few years later she got back to the island at night and saw another immense dawn lift-off. She then realized what an extraordinary sight she was witnessing.

Maybe a little too extraordinary; Sanders could hardly believe she’d stumbled on thousands upon thousands of Whimbrels, and so perhaps it’s not surprising that she had a hard time convincing some of the experts she contacted that she had really found what she’d found.

“They honestly couldn’t believe the numbers,” she said. But then she reached out to Andy Johnson, a multimedia producer with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Sanders had met Johnson years earlier on a bird survey in Churchill, Manitoba, when he was researching a Cornell undergrad thesis on Whimbrels.

State wildlife biologist Felicia Sanders takes a special pride in the Whimbrel roost on Deveaux Bank, not for her discovery, but for her state. “It’s something special,” she says, “that is maybe nowhere else in the world.” Photo by Andy Johnson.

Andy Johnson met Sanders as a Cornell undergraduate when he was surveying Whimbrels in Churchill, Manitoba. Johnson is now a multimedia producer with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

“He rallied the Cornell troops. I took some cellphone videos, and he’s like, ‘Good enough for me, we’re coming down to document this amazing phenomenon,’” Sanders said. “He knew a lot more about Whimbrels than I did, and made me realize it’s something special that is maybe nowhere else in the world.”

In the spring of 2019, Johnson and wildlife cinematographer Matt Aeberhard spent almost a month at Deveaux, on night-long vigils in photo blinds surrounded by thousands of Whimbrels that they filmed with infrared cameras.

“I keep coming back to those moments when the light has fallen and you’re surrounded by these swirls of birds,” Johnson said. “It’s sensory overload because it’s dark and you can’t see what’s going on, but there’s that elemental sense of sharing that tiny spit of land with the Whimbrels in the middle of their journey, connecting these disparate parts of the hemisphere… it’s the sense that you’re connected to something cosmic and huge, very intimately and directly connected to it.”

There are two main populations of Whimbrels in North America. The western group breeds from the Northwest Territories along the Mackenzie River delta into western Alaska, while the eastern group nests south and west of Hudson Bay. It is these Hudsonian birds, which some experts consider a separate species, that are thought to make up the bulk of the Whimbrels passing through Deveaux in such great numbers each spring. Come autumn, they head south through the Great Lakes to the coast of South Carolina or Georgia, staging together in much smaller numbers than in spring, and then follow the arc of the Bahamas and Antilles to the northeastern coast of South America.

That means they’re flying right into the storm-raked region known as Hurricane Alley. A recent paper authored by Whimbrel expert Bryan Watts of the Center for Conservation Science showed that 13 of 18 tagged Whimbrels taking this route encountered tropical storms or powerful hurricanes. Many of them were forced to rest and recover on the islands of the Lesser Antilles, where they are vulnerable to hunting. In French-controlled overseas departments such as Guadeloupe and Martinique, the largely uncontrolled shooting of shorebirds remains legal; Guadeloupe is even advertised internationally for its shorebird “destination hunts.”

Watts and others have analyzed what’s known of the hunting mortality in the Caribbean and South America and conclude that it alone may account for much of the long decline of eastern Whimbrel numbers, which have dwindled steadily since at least the 1970s. The best benchmarks for the eastern population come from an annual Whimbrel count on the Delmarva Peninsula of Virginia every spring, where between 1994 and 2009 Watts and his colleagues documented a 50% decrease. They recently updated those figures through 2020, and found that the same rate of annual decline continues.

Read More

The discovery of the global importance of Deveaux Bank has sparked a belated focus on the importance of nocturnal roosts in general, which may be among the most important, rarest, and least-appreciated resources for long-distance shorebird migrants like Whimbrels. At night, these birds need safe places, far from land predators like raccoons and owls and high enough above the waves that even astronomical peak tides twice each month will not submerge them. Sandbars and newly accreted barrier islands serve perfectly, but they are often swept away by storms, and many dammed and altered river systems no longer provide the sediment to rebuild these ephemeral lands.

“There aren’t that many options for the Whimbrels,” Sanders said. “I go to places where I think Whimbrels would roost, and I realize this site’s got too many predators, that site’s got too many pelicans. A lot of the coast is armored, the rivers are dammed, there aren’t that many choices like there were historically for these birds to roost. I think nocturnal roosts are a really big limiting factor for shorebird distribution.”

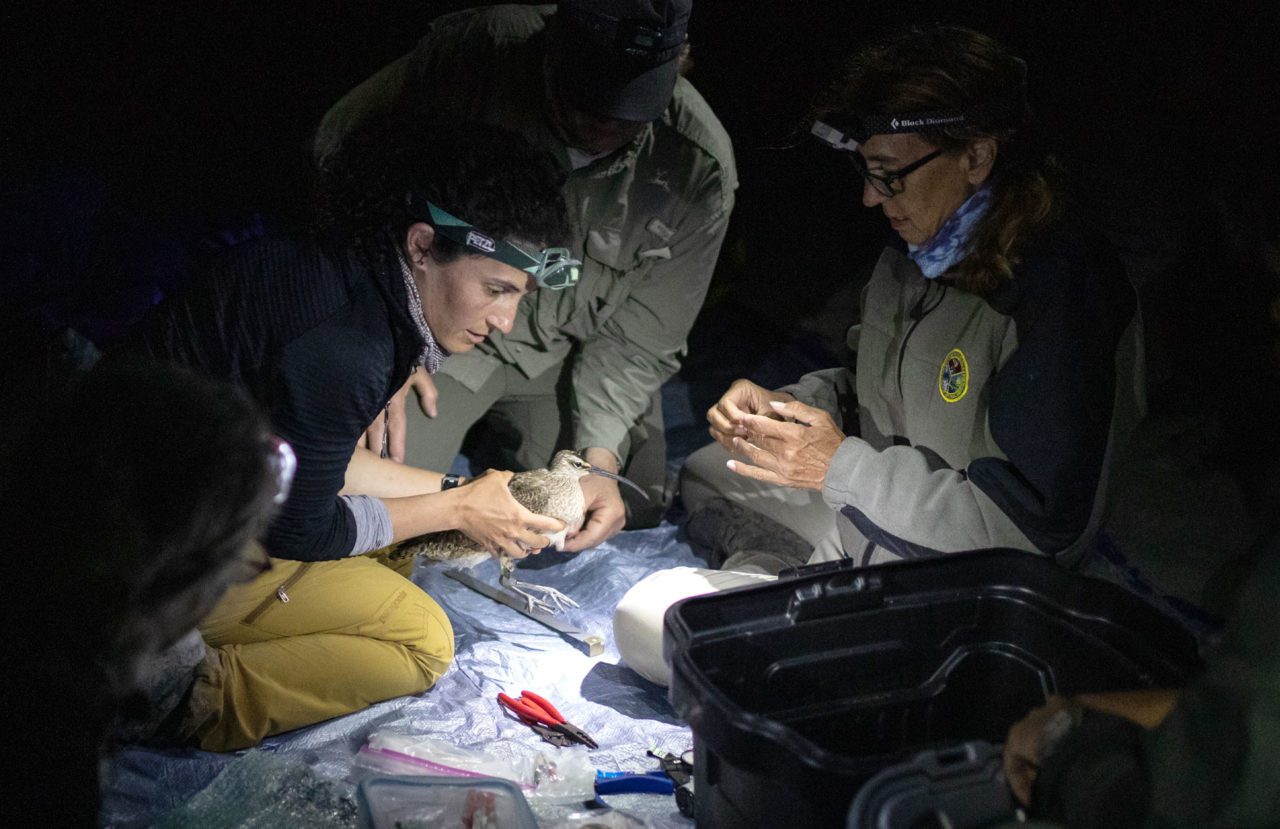

Adding to the complexity of the issue is the profound personality change, from irascible loners to amiable flockmates, that Whimbrels undergo from day to night. One evening on Deveaux—having just helped Sanders and her team set up a cannon net to catch Whimbrels for fitting with GPS tracking tags—I hunkered among the dune grass with Abby Sterling, the director of Manomet’s Georgia Bight Shorebird Conservation Initiative. Sterling, Johnson, Aeberhard, and others helped Sanders conduct the first rigorous counts of Whimbrels on Deveaux in 2019, tallying up to 19,485 birds gathered together in a single night.

But she and I watched one Whimbrel with no such desire for companionship. Instead, it fiercely defended a swath of mudflat pocked with the burrows of tasty fiddler crabs, much to my surprise driving away any other Whimbrel that landed there.

“They’re very territorial when they’re feeding, which is weird, because they’re so ridiculously social when they gather in these huge flocks to roost,” Sterling said.

That dichotomy has enormous ramifications for Whimbrel conservation. During the day, they spread out across an immense area to forage. Fortunately for the birds, the Carolinas and Georgia together have the largest expanse of saltmarsh on the Atlantic coast, nearly 1 million acres. Just south of Deveaux lies the 350,000-acre ACE Basin Project, a federal-state-private partnership that protects a vast stretch of especially pristine tidal estuary.

So the Whimbrels have plenty of places to hunt, Sterling explained. But come darkness, they have vanishingly few places where they can safely roost. Surveys along the Georgia and South Carolina coasts have revealed only two other such sites: Little Egg Island in Georgia, and Tomkins Island just across the state line in South Carolina, each holding only 1,000 or 2,000 Whimbrels. Deveaux is not only the largest night roost on the Southeast coast, it is by far the largest known in the world.

Preliminary tracking data, including that from several Whimbrels trapped at Deveaux during my time with the team last spring for research by University of South Carolina PhD student Maina Handmaker, show some birds may be commuting up to 30 miles each way between foraging areas and roost sites. That’s expensive travel. New research from Bryan Watts and his colleagues suggests such daily commutes may cost a Whimbrel up to 20% of its premigratory energetic budget, fat it needs for the next leg of its hemispheric journey.

Biologists often talk about the need to study the full-cycle biology of a migratory bird—their annual cycle from nesting to migration to nonbreeding grounds and back. But the Deveaux Whimbrels remind us that knowing a bird’s full daily cycle may be just as critical to saving it.

In a sense, the discovery at Deveaux was a rediscovery. More than a century ago, ornithologists and shorebird gunners recognized the huge numbers of Whimbrels passing north along the Southeast coast. In his Life Histories of North American Shorebirds, published in 1929, Arthur Cleveland Bent quoted an acquaintance who said that during peak migration, hundreds of thousands of Whimbrels could be seen in a day. Herbert K. Jobs, another of Bent’s correspondents, described exactly the sort of nocturnal roost as Sanders had found at Deveaux, occurring on “several little low islands—mere sand bars” off the South Carolina coast. “I hazard a guess that there are often 10,000 curlews at such a roost each night,” he noted in 1905. “At the first glimmer of day they are off again for the marshes.”

Where Jobs saw coastlines largely empty of people and awash with birds, today the reverse is true. We motored out to Deveaux on Mother’s Day afternoon, with hundreds of boats full of happy holiday-goers cruising the North Edisto and waters off nearby Seabrook Island. A dozen boats were pulled up along the two ends of Deveaux Bank open to the public, picnickers amid a backdrop of wheeling Brown Pelicans and Laughing Gulls nesting in the closed areas just beyond.

“Deveaux just feels like a place back in time, before we changed all these processes that make really important habitat for birds. It’s like this little piece of what it looks like when everything goes right,” Abby Sterling later told me. “But it’s a tricky place, right? There’s a history of people from Rockville using that spot, the local community values that place. It’s used by people and it’s critical for birds.

“[But] all these birds have nowhere else safe to go for the night. There is no other Deveaux Bank.”

Felicia Sanders has spent years cultivating local concern for, and pride in, the welter of nesting birds that populate Deveaux. I saw both emotions expressed repeatedly by area residents who chatted up Sanders when she was readying the DNR boats at the public launch, people telling her about nesting ospreys or oystercatcher sightings. When she explained to one fisherman how important Deveaux was for Whimbrels, he excitedly shared stories of seeing huge flocks come in at dusk.

But Sanders, Sterling, and the team of scientists admitted they have been nervous about making the news of the massive Whimbrel night roost public. Frankly, they seemed less concerned about additional pressure from area residents, who tend to use Deveaux and the waters around it during the day, than from birders and photographers.

“I’m a little more worried about people that may want to come out and see this incredible spectacle,” Sterling said. “The birds come here because it’s safe, it’s remote. If they’re flushed, they literally have no place else to go when the tide is high and it’s dark.”

South Carolina DNR officers patrol the area around Deveaux, but they can’t be there all the time.

Shorebirds and Seabirds of Deveaux.Whimbrels and Marbled Godwits stand at water's edge on Deveaux Bank. Marbled Godwits are on the Partners in Flight Yellow Watch List. Photos by Andy Johnson.

Deveaux Bank is also home to the largest Atlantic coast colony of breeding Brown Pelicans.

Laughing Gull populations are threatened by habitat development and disturbance to nesting beaches. They, too, use Deveaux Bank.

Whimbrels at their evening roost at Deveaux Bank.

There is no other Deveaux Bank; it’s a point Sanders, Maina Handmaker, Andy Johnson, Bryan Watts—almost everyone involved in Whimbrel research—made to me again and again. Roost sites safe from predators and disturbance, high enough to stay above the highest tides, are all but nonexistent along this part of the coast.

But what if there were more Deveaux Banks? Given the physical limits to how far a Whimbrel can commute in a day, is it possible to use spoil material from coastal dredging operations to create new roost sites, strategically placed to open up huge new areas for feeding? Some biologists think so.

“You can imagine that if 20,000 [Whimbrels] are focused there at Deveaux, and they have a limited sally distance each day, that we could support a lot more if we had another Deveaux in, say, south Georgia,” Watts said. “There’s a lot of available forage habitat down there that’s currently difficult for the birds to access because there’s no night roost.”

A group of Whimbrel experts headed by Sterling’s boss at Manomet, Brad Winn, is working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and agency partners on a plan to create more shorebird habitat when the Intracoastal Waterway is dredged or harbors are deepened, using the spoil material to create habitat for Whimbrels and other birds. Planning for such projects is time-consuming, Sterling cautioned.

“When they have that dredge material and it’s of sufficient quality, we need to have conversations well enough in advance so that material can be put to other uses, including building habitat,” she said.

Watts also stressed that limiting Whimbrels’ exposure to hunting should be a priority. Conservationists have made progress limiting illegal shooting in Atlantic Canada by the owners of commercial blueberry barrens, who get upset when Whimbrels feed on their crop. Guadeloupe suspended hunting of Whimbrels this year, and on Barbados, hunt clubs have voluntarily instituted no-hunting lists, while the island hunt committee and BirdLife International have established no-hunt preserves. On the other hand, the French-controlled island of Martinique has proposed a shorebird hunting season running nearly seven months and permitting gunners to kill up to 10 Whimbrels each (assuming such limits are even enforced). The research Watts and others have done on mortality rates makes it clear that Whimbrels are one of several species, along with Red Knots and Buff-breasted Sandpipers, that simply can’t withstand the added pressure of hunting.

“They just don’t have the population size or demography to sustain it,” he said, insisting that such species should be placed on no-hunt lists.

University of South Carolina graduate student Maina Handmaker (center) has been studying the stopover ecology and migratory performance of the Whimbrels that roost on Deveaux Bank. Photos by Andy Johnson.

After catching a Whimbrel, biologists take measurements and may attach tracking devices to study their movements.

Handmaker’s tracking of Whimbrels tagged on Deveaux Bank shows that some birds are flying 30 miles to feed in marshes farther inland and back every night to roost.

A transmitter is carefully attached to a Whimbrel.

With its transmitter securely attached, the Whimbrels is released on site to return to its normal activities.

My last night on Deveaux was a dramatic one. For seven weeks, Sanders and Handmaker had been struggling to catch Whimbrels to tag and track, but the birds—which are, after all, intensely hunted in many of their wintering areas—had proven almost supernaturally wary, avoiding the cannon nets and other traps. This night, though, high tide coincided with nightfall and a dark-moon period. There would be no wind and thus little surf, so it was a rare chance to safely land on a small sandbar beyond Deveaux where most of the Whimbrels had taken to roosting. The team set several mist nets there before sunset, waited for full dark, then managed to flush 14 Whimbrels into them.

For once, luck seemed to break Handmaker’s way—until the western horizon began flickering with lightning. The wind rose, the muggy air grew chilly, and radar images on our phones showed massive blobs of yellow, orange, and red moving relentlessly our way. A tiny, exposed sandbar miles out to sea seemed a very bad place to be in a thunderstorm, but the careful, fiddly work of fitting transmitters on shorebirds couldn’t be rushed. By midnight, having banded, processed, blood-sampled, and tagged just two of the Whimbrels with Handmaker’s GPS loggers, Sanders made the difficult call to release the rest of the birds unmarked. Ten of us rapidly and unceremoniously piled our gear into two open Boston Whalers and made a heart-stopping sprint for shore, the final few miles through lashing rain, wind, and thunder that boomed in endless percussion.

And yet for all that drama, the moments to which my mind mostly keeps returning occurred on my first evening at Deveaux. I stood alone then in the gathering darkness at a far corner of the island. Flat gray clouds clotted the faintly pink sky on the western horizon. Behind me the Earth’s shadow was rising, that half of the sky cold and blue-black, reflected in the blue-black ocean against breakers that smashed white. The Whimbrels still poured through, silhouettes coming from the west in jumbled flocks of a few dozen to maybe a hundred each, hugging the dunes, vanishing into the gloom as soon as they passed me.

In the last vestiges of twilight, a flock of a few dozen Whimbrels appeared right in front of me, at head height, only yards away. Without thinking—and not from any defensive instinct, really for no reason I can now imagine—I threw my left hand high into the air, fingers wide, just as they barreled around and past me in a great rush.

And I felt…something. Perhaps the brush of primary feathers on my fingertips. Maybe just a gust of the sea wind. Maybe a little of the urgency that carries tens of thousands of birds on slender wings from Venezuela to the Arctic and back, and on this night to a newborn spit of sand on the South Carolina coast.

Whatever it was, I stood, breathing hard, my arm still raised like a benediction, as the night swallowed them.

Writer and migration researcher Scott Weidensaul is the author, most recently, of the New York Times bestseller A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds (W.W. Norton).

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you