A Long-Awaited Homecoming for Peregrine Falcons in the Finger Lakes

Story and photos by Andy Johnson

Montage: a young Peregrine Falcon and Taughannock Falls. October 13, 2021A half-century after DDT put them on the Endangered Species List, Peregrine Falcons finally returned to their storied aerie at Taughannock Falls, New York. We were there to bear witness.

From the Autumn 2021 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

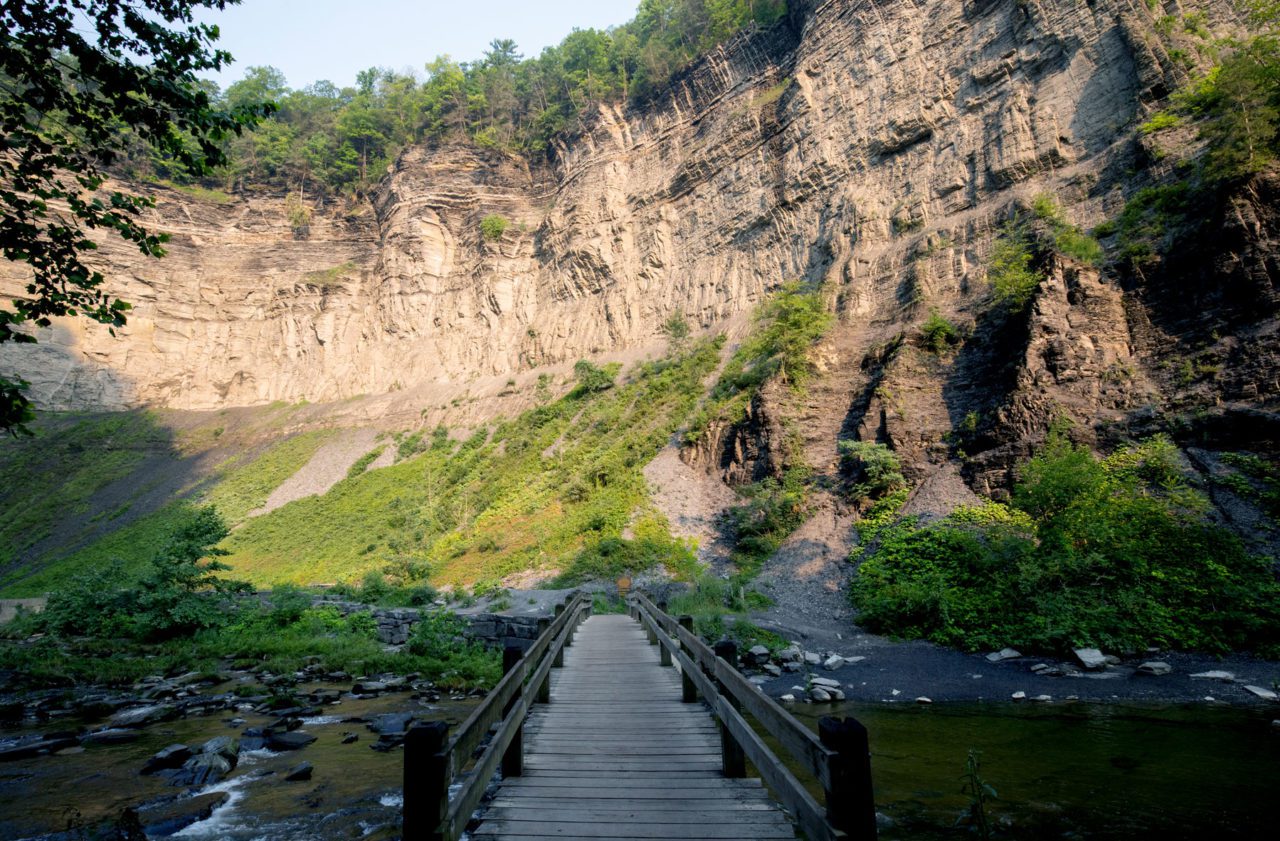

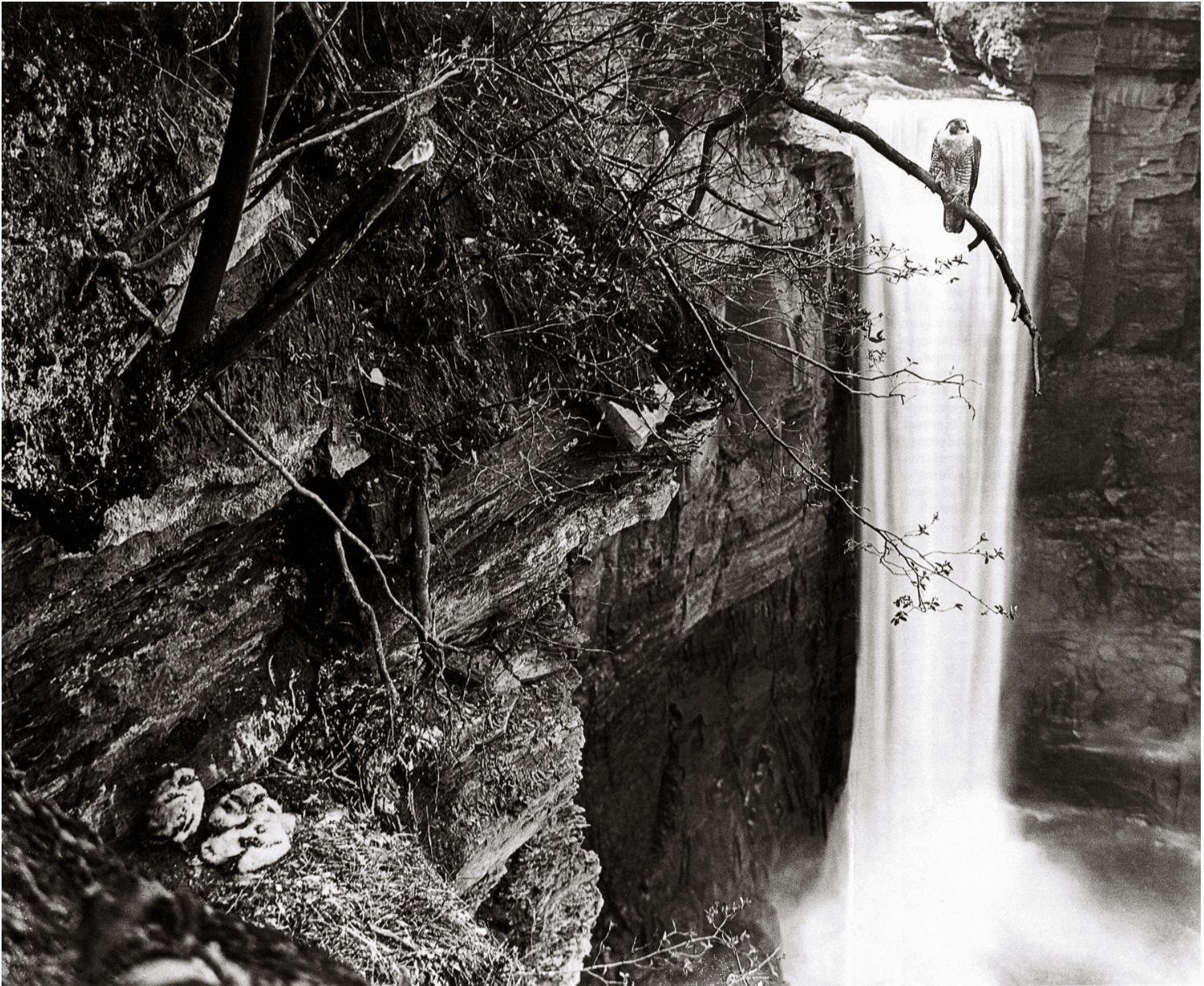

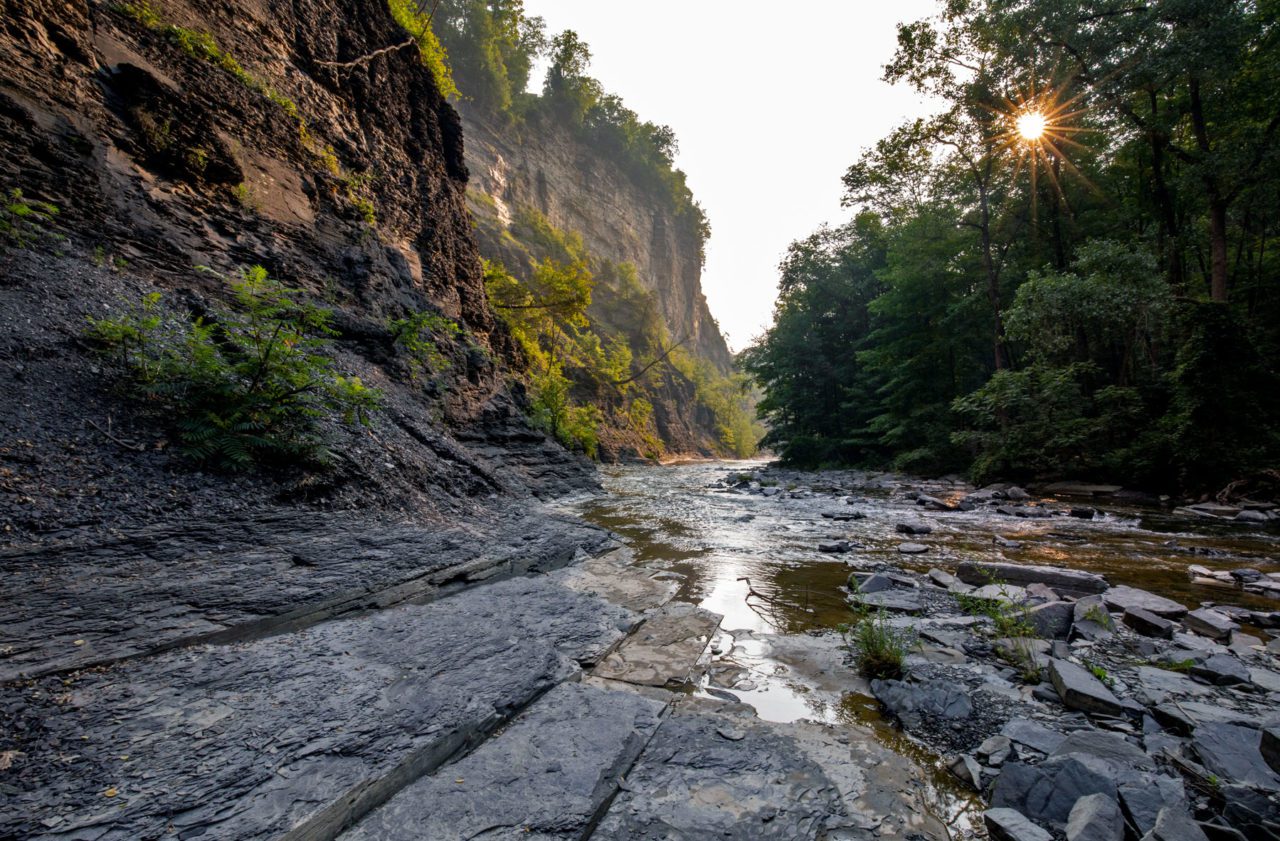

Just a few miles north of Ithaca, New York, Taughannock Creek (pronounced tuh-GAN-uck) carves between the sheer rock walls of a 400-foot gorge, dropping toward Cayuga Lake in a free-fall curtain of water taller than Niagara Falls. There’s a state park trail up this gorge, with a sun-faded sign at the trailhead that bears a monochrome photograph of a Peregrine Falcon perched by her cliffside nest, hulking protectively over three downy white chicks. Framed by the white waters of the Taughannock cataract, the peregrine mother is a picture of power: her velocity-hewn teardrop shape is steadfast, even as the film’s long exposure captures the water rushing by. Her gaze is transfixing, even through the sign’s grainy, faded ink and the century that now separates us.

The photograph was taken at Taughannock Falls in the 1930s by renowned Cornell University ornithologist and Cornell Lab of Ornithology founder Arthur Allen. A few short decades after that photo, however, the cliffs at Taughannock were empty—and Peregrine Falcons were nearly wiped from the continent altogether. A nationwide recovery effort, centered at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, ensued to deliver the Peregrine Falcon back to the wild later in the 20th century. But even after a remarkable population rebound in North America, and after peregrines were delisted from the Endangered Species Act, falcons were still missing from Taughannock on my early-morning walks there in the spring of 2020.

It was the early weeks of COVID’s sweep across the United States, in March 2020, and I sought respite on walks along Taughannock’s ice-chocked creek, passing that familiar trailhead sign as I went. Taughannock’s walls—with the slanting sun revealing their rugged contours and myriad ledges—practically begged for those cliff-dwellers from Allen’s photograph.

And then on one brisk afternoon walk, craning to peer up at the looming gorge overhead, I saw Peregrine Falcons again.

The waterfall at Taughannock gorge drops more than 200 feet, making it the tallest free-falling waterfall in the northeastern United States—even taller than Niagara Falls. Photo by Andy Johnson.

A mile long trail leads through the gorge to the waterfall. Photo by Andy Johnson.

The large creek running through the gorge can range from calm to fast depending on rainfall. Photo by Andy Johnson.

The gorge is hundreds of feet deep and often shrouded in mist, giving it an otherworldly feel. Photo by Andy Johnson.

A new day begins at Taughannock. Photo by Andy Johnson.

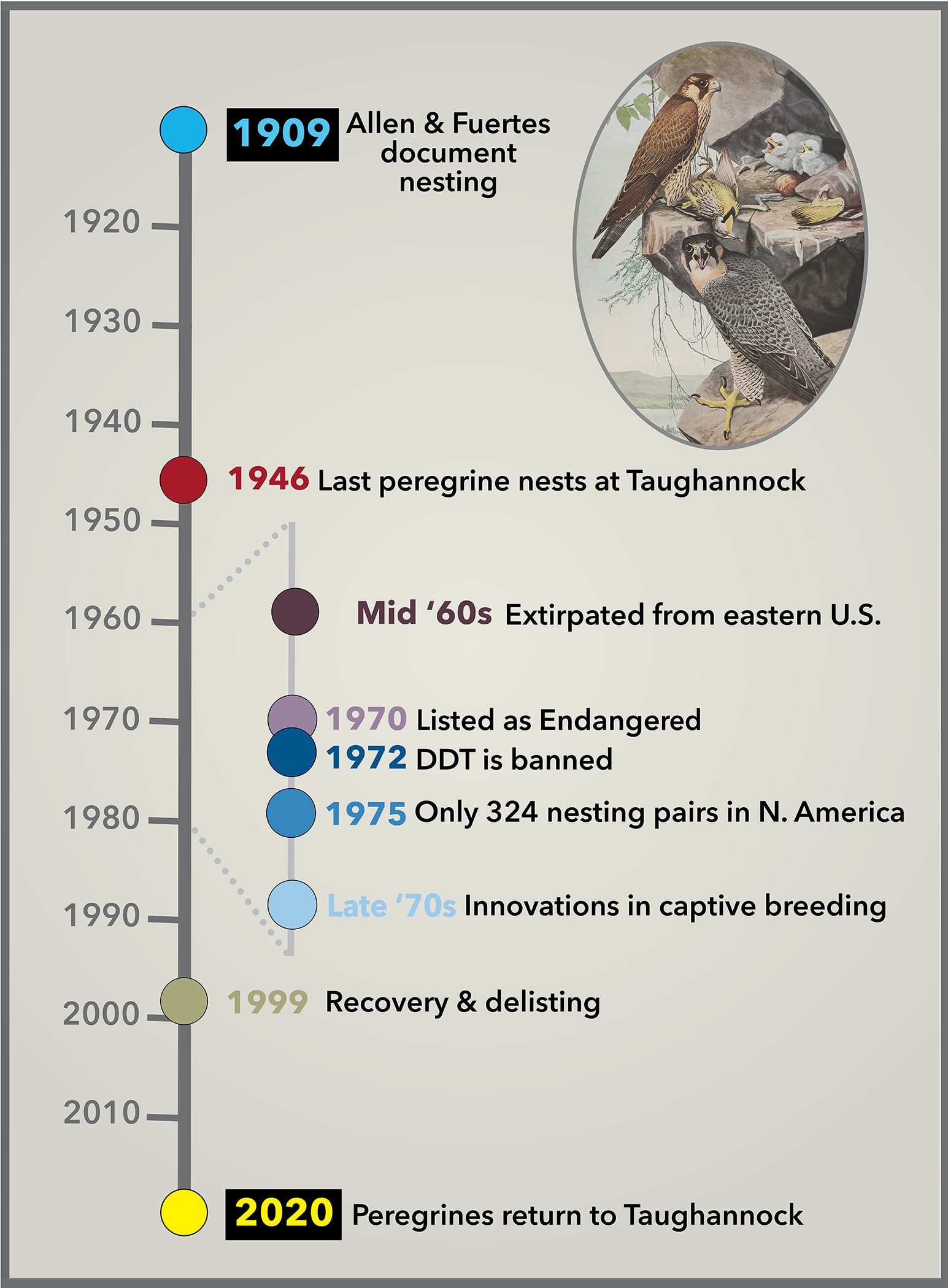

In the wake of receding glaciers some 10,000 years ago, Peregrine Falcons occupied cliffside aeries across northern latitudes. In eastern North America, home range of the anatum subspecies, the peregrine’s likeness was repeatedly invoked in the artwork and lore of the Mississippian civilization (which prospered for nearly a thousand pre-Columbian years). More than a century ago, in 1913, Arthur Allen penned a detailed account of a nesting pair at the Taughannock gorge for the academic magazine Bird-Lore, after “a Peregrine Falcon espied this cleft in the earth and chose it for his aerie.”

In the following decades, Allen and his friend and colleague, the eminent ornithological painter Louis Agassiz Fuertes, documented the falcons breeding at Taughannock in evocative writings, paintings, and photographs. Their depictions are definitive renderings of the species, capturing their kinship with the craggy ledges high above Cayuga Lake, and the echoing of their screams between canyon walls.

“One forgets everything in the excitement of that scream, which announces the return of the provider,” Allen wrote. “Every bird in the covert crouches and freezes immovable when he hears it.”

That unbroken line of anatum falcons, captured at their zenith in the family portrait on the park sign, unraveled in mere decades. In the late 1940s, as postwar America was beginning to boom, the nation’s agricultural engine boomed, too—and it began exhaling dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane: the notorious DDT.

After shielding millions of troops from mosquito-borne illness during the Second World War, DDT flourished commercially in the United States as a pesticide to protect gardens, pets, orchards, croplands, and livestock. Ironically, the new insect killer was canonized as a life-saving technological marvel, even earning its discoverer the 1948 Nobel Prize in medicine. But the poison entered soils, leached into waterways, and climbed up the food chain meal by meal. Upon reaching the tissues of apex birds of prey—Peregrine Falcons and Bald Eagles most prominent among them—DDT thinned the shells of the eggs they laid. Nests failed consistently, and populations fell precipitously.

The last nesting pair of Peregrine Falcons in Taughannock gorge was recorded in 1946. By the mid-1960s, there wasn’t a single nesting pair east of the Mississippi River. Another decade later, some 90% of peregrine aeries along the Pacific Coast also lay silent. By 1975, there were only 324 known nesting peregrine pairs across all of North America.

Rachel Carson spoke out about the lethal dangers of DDT. In a nationally broadcast television interview after the 1962 publication of her book Silent Spring, she said: “We have now acquired a fateful power to alter and destroy nature. But man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself.” If left unregulated, Carson warned, this chemical marvel DDT would become our undoing.

But it wasn’t too late. An environmental awakening quickly found traction, beginning with multiple Senate hearings on pesticides within a year of Silent Spring’s publication. The Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969, which paved the way for the present-day Endangered Species Act, listed the Peregrine Falcon in 1970. The Environmental Protection Agency, formed that same year, banned the use of DDT in 1972.

Meanwhile, in the quieter hills of Ithaca, New York, another movement was rallying in support of the dwindling falcons. A Cornell University expedition in 1967 ventured to the farthest corners of North America to find Peregrine Falcon aeries that still lay beyond the insidious reach of DDT. Near Alaska’s Colville River, on rocky tundra headlands, biologists collected young peregrines from healthy, wild nests. These birds, along with others contributed from around the world by a tight-knit and passionate network of falconers, were the beginning of an audacious effort to breed peregrines in captivity and reintroduce them to bolster wild populations.

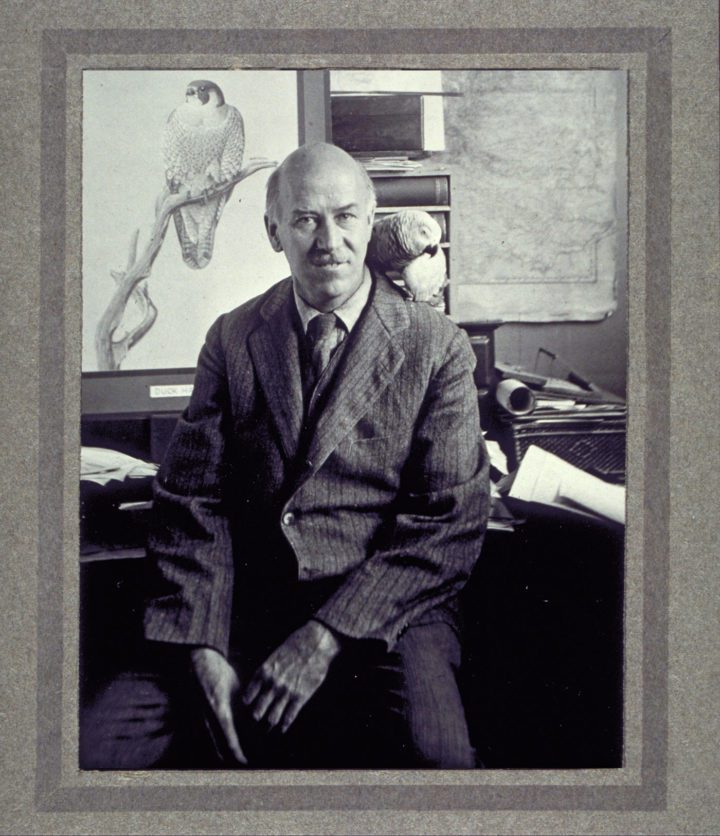

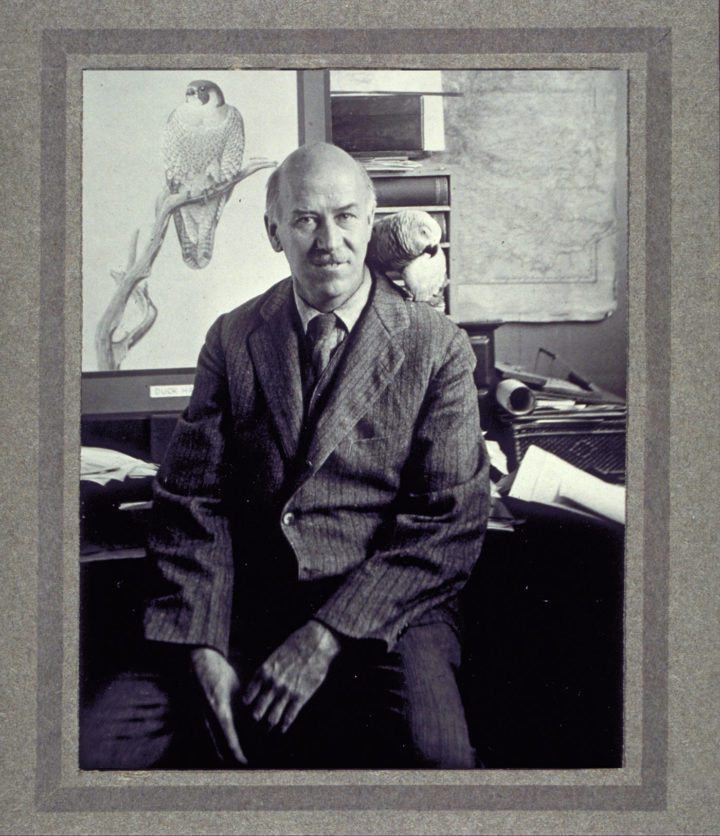

Louis Agassiz Fuertes in front of one of his peregrine drawings. Photo courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University.

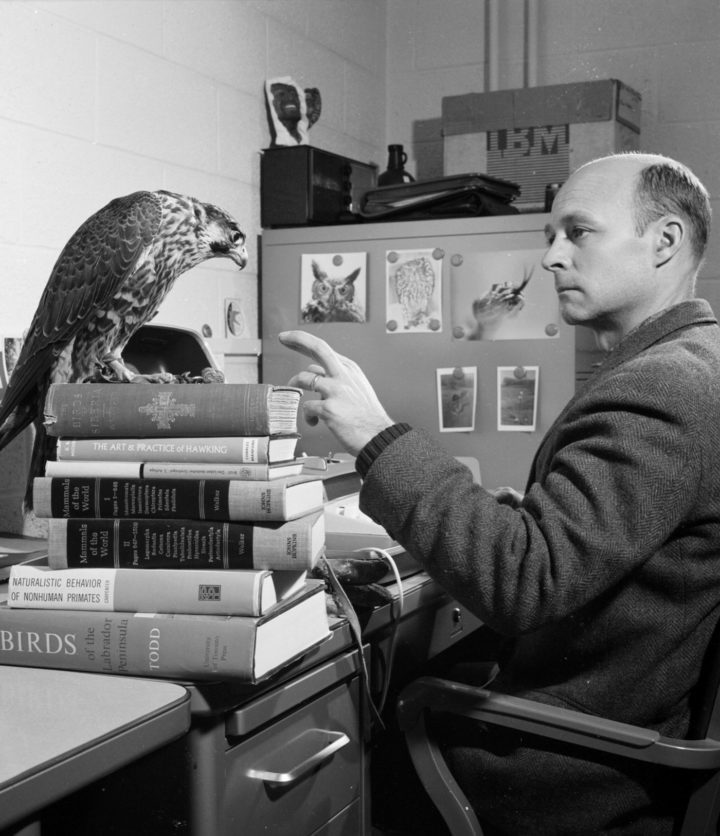

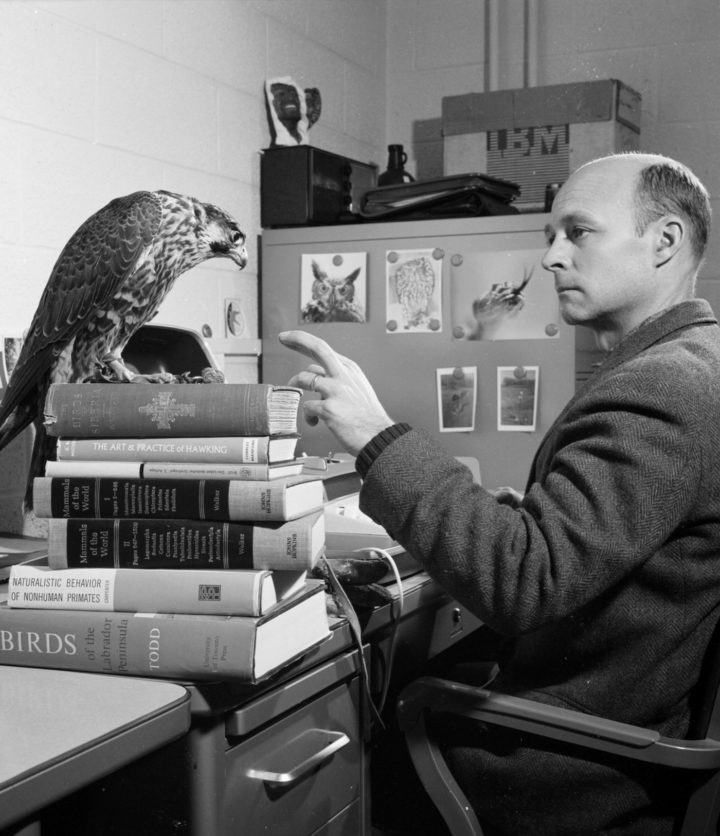

Dr. Tom Cade at work. Photo courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University.

Dr. Tom Cade, a zoology professor at Cornell University and research director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, cofounded what became The Peregrine Fund in 1970. The work of captive-rearing and wild reintroduction of falcons that Cade and his colleagues pioneered was widely thought to be impossible. But the team leaned on centuries of accrued knowledge from falconry, adapting old techniques to suit present needs. Hack towers—elevated platforms traditionally used to give young falcons flight experience before training with lures—were employed to give captive-bred falcons a jump start in the wider wild, once the time came to fledge.

In the 1970s, 50 captive-reared peregrines successfully fledged from hack sites across the Northeast. Over the next two decades that tally rose to 1,600. By the end of the 20th century, more than 6,000 young falcons had been released into the wild across North America by The Peregrine Fund and other academic and nonprofit groups, as well as state and federal agencies. The reintroduction efforts met with unexpected success and gained traction with proud local communities in metropolitan centers like New York City, Minneapolis, and Chicago where falcons took to the gravelly ledges of high-rise buildings and bridges.

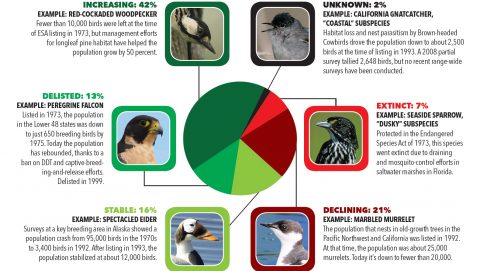

In 1999, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service press release heralded landmark news: “Today, the world’s fastest bird soars off of the Endangered Species list.” As one of the Endangered Species list’s inaugural members, the Peregrine Falcon’s removal from its ranks was an acknowledgment of an unprecedented recovery, and a culmination of the act’s grand experiment. Conservationists rang in the new millennium on a high note.

Two decades into the 21st century, however, the trailhead photograph at Taughannock Falls State Park still showed a relic of the past. But as I neared the falls on that afternoon walk in March 2020, I heard the same raking call that had first halted Arthur Allen here in 1909. It seemed an ancestral echo, carried across the lost decades, cutting through the din of water and reflecting off the gorge walls. I turned to see two Peregrine Falcons flying side by side, directly overhead, racing upstream. The male landed on the cliff and nearly vanished, a mere speck on the rock face. The female sped on, past the falls and out of sight.

It had been over a century since Arthur Allen chanced upon the same sight, nearly 75 years since Taughannock was last adorned by Peregrine Falcons in residence. And it had been exactly 50 years since The Peregrine Fund had begun its bold work to replenish the empty territories of North America with a new line of aerial monarchs.

Throughout that spring, I made frequent morning visits to Taughannock. On April 5, scanning the countless ledges and shadows from across the gorge, I finally caught sight of the female peregrine, hunkered low on a flat, sandy ledge near the top of the opposite cliff. She was incubating. She had chosen this ledge at Taughannock and found a mate to join her.

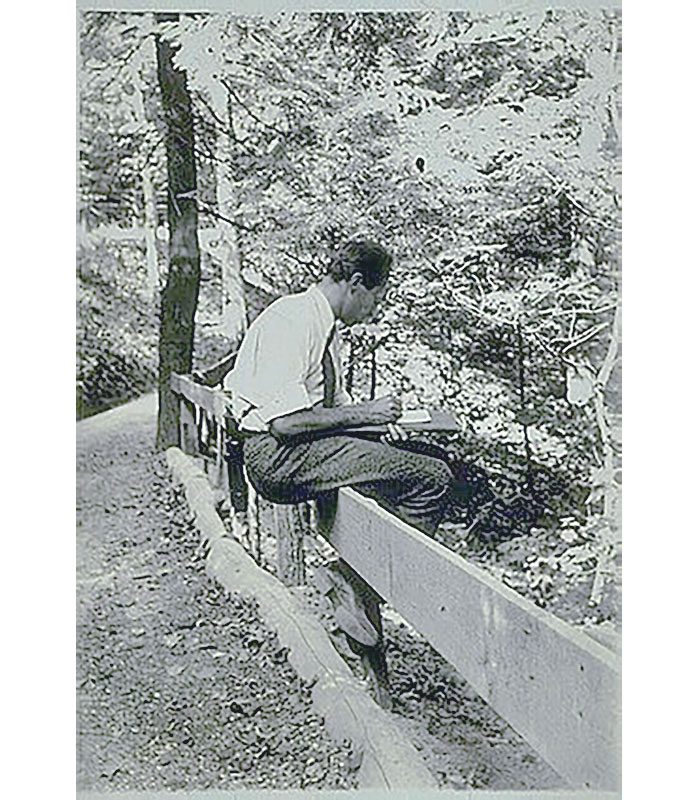

Louis Agassiz Fuertes sketching in Taughannock Falls. Fuertes and Arthur Allen first recorded peregrines at this site in 1909. Photo courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University.

After nearly 80 years absence, Andy Johnson recorded peregrines at Taughannock. Johnson is a multimedia producer for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

For me, a multimedia producer for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the potential to document peregrines rearing their young at Taughannock—so close to my own home, when other assignments were canceled by COVID lockdowns—was a small miracle. My job quickly pivoted to filming this historic nesting season. The Peregrine Falcon is still listed by the state of New York as an endangered species (this pair joined the growing ranks of more than 50 nesting pairs across the state), so we collaborated closely with biologists from the New York Department of Environmental Conservation and New York State Parks to secure permits and plan an unobtrusive—and secretive—approach to filming. Although peregrines are notoriously aggressive near their nests (unwilling to tolerate visitors, but by the same token, unlikely to abandon in the case of intrusions), my first priority was ensuring this nest would not be disturbed.

Read More

I walked the rim trail on the far side of the gorge with park biologists to find a clear vantage point, without trampling any rare or sensitive plant species. Options were few on such a steep slope, but eventually we settled on a small outcrop atop the precipice, opposite the falcon’s nest. It was accessible by a sliding scramble, with me harnessed into safety lines lashed around a sturdy hemlock. I gained new appreciation for Arthur Allen’s descriptions of navigating a treacherous slope for a hard-earned and intimate view of a peregrine nest a century earlier.

“One may clamber down the steep slope ending in the precipice, and make his way to the edge of the cliff,” wrote Allen. “Ten feet down the face of the cliff, an old gnarled cedar still clings with its tenacious roots…letting oneself down a rope to this swaying tree, an even better view can be secured. One occasionally came to his senses with a start, after reaching far out with the camera and temporarily forgetting his position astraddle the branch.”

Instead, we had a clear view with comfortable standing room, albeit nearly 500 feet from the nest. In those early morning hours of watching, the female tended more toward incubation duty, while her smaller mate tended to preen and sun himself on exposed snags partway down the cliff. Once in a while he seemed to suddenly have recollections of other duties, and would set off on stiff wings to make forays across the forest edges, farm fields, and lakeshores of their vast hunting range.

I stood holding my breath ready to film as the male returned with the telltale deep wingbeats of a prey-carrying flight. I glimpsed a large flash of yellow tucked beneath him, and immediately recalled a Fuertes painting of a falcon pinning a meadowlark against the shale ledge, its bright yellow breast turned to face the sky over Cayuga Lake. And now it seemed these very characters were converging again into a living diorama.

Or at least, that’s what I anticipated. The male peregrine wasn’t so swayed by any reverence for Fuertes and thought it better to take the meadowlark farther up the gorge and around the next bend to enjoy the meal in solitude. He returned empty-taloned about 10 minutes later to preen. The female, still incubating, glared—albeit with the same severe expression she always wore.

In the passing weeks, though, the male did share enough of his meals, and the female took her own breaks from incubation to preen and hunt, so that one day I arrived to a different view. In place of the rusty speckled arcs of eggs, I could just make out a compact mass of downy white. With great effort, three little bespectacled cotton balls rose briefly from the pile of down.

Through my spotting scope, that image seemed to distill a winding history into a single, concentrated moment. The three new lives, soft and bright white, were conspicuous and vulnerable against the hard shale cliff, resting just a few precarious inches from the precipice. Simply by hatching, by breaking out of strong, fully calcified eggshells, they had earned a chance to live. In their first hours of life, and in spite of myriad gauntlets yet to clear, they were pioneers and rightful inheritors of a new world, finally restored.

Five weeks later, the three growing falcons were absorbed in curiosity. While they exercised their wings or rested in the shade, they drank in the sights and sounds of their home gorge, studied the flight patterns of Rough-winged Swallows and Blue Jays below them, and watched each other for cues, missteps, and breakthroughs. When one hopped to a new ledge, their world expanded together. The others were rapt, tilting and bobbing their heads to take full measure of the new distances now within reach.

On June 9, 2020, the first of the young falcons leapt from the ledge, taking unsteady but successful flight across the gorge and alighting back on the cliff wall below the nest. The others hesitantly followed suit later that day. After fledging, the young would return to the nest ledge to roost at night, hunkering back into their familiar sanctuary after long days of exploration and learning. The venturing young birds soon discovered a dead hemlock trunk that reached out almost horizontally into the gorge, affording an expansive view from which to rest and preen.

As luck would have it, this newfound real estate was on my side of the gorge, jutting out just below my vantage point. As one of the fledglings took flight from the nest ledge, I watched it glide below eye-level straight toward me, crossing the creek far below, and swooping up to land on the near snag, backlit and radiant. The adults’ slaty plumage was dusty and worn by this point in the season, but the juvenile seen up close sported buff-colored banding and scalloping on its fresh new feathers, and even a little tuft of down still on its head. It turned on the perch, adjusting its clumsy-taloned grasp and beating its wings to regain tentative balance. While the young bird was still finding its footing, it was every inch a Peregrine Falcon.

By August, the gorge was quiet once again. The falcon family had departed on migration, streaks of white guano beneath the empty ledge the only sign left of their return. Months later, deep in the winter of 2021 and well before the first signs of a new spring, two svelte adult peregrines returned to the gorge and began their rituals anew, flying in unison, reorienting to the sensation of shale underfoot, and undertaking the serious work of growing their numbers, a few hard-shelled eggs at a time.

As of this printing in late summer 2021, Taughannock’s wild Peregrine Falcons have embarked on their next half-century with a resounding affirmation of past progress. This year they successfully fledged another four young.

To watch young falcons emerge from the mouth of Taughannock two years in a row, toward new gorges yet to be found, was thanks to a far-reaching and defiant vision. The decades-long recovery—a bold experiment to reel a species back from the brink of extinction with our own hands—was characterized by the uncompromising tenacity of a few people who had faith in the impossible, and a commitment to ends that might not be realized in the span of a human lifetime.

In February of 2019, at age 91, Dr. Tom Cade passed away, perhaps in the same moment that wild Peregrine Falcons first canvassed Taughannock gorge for nesting. He certainly would have loved to see Peregrine Falcons here in Taughannock, further culmination of a life’s work—a new line of peregrines completing a homecoming of their own accord, and a fully fledged testament to the long span of tireless work poured into recovering their forebears.

Andy Johnson, Cornell ‘14, is a producer in the Center for Conservation Media at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you