Tropical Birding Along Peru’s Famous Northern Route

By Tim Gallagher

April 15, 2008

Peru is a magical place—especially for birders. Boasting more than 1,800 species, it holds one-fifth of the world’s avifauna, a staggering amount for a single country. Last fall I was invited to take part in a tour of Peru’s northern birding route through the Andes, followed by a nature fair. The trip was set up by the national tourism bureau, PromPeru, to promote ecotourism in a part of the country that receives far fewer visitors than the popular Inca ruins of Machu Picchu and Cuzco to the south. The group invited journalists, prominent birders, and representatives from tour companies.

Of course, I jumped at the chance to visit Peru. It has been a dream destination of mine for years—for the birds, most of which I’d never seen before, but also for Peru’s rich history in ornithology. It was there that many of the most prominent ornithologists in the United States cut their teeth: people like John O’Neill of Louisiana State University; John Fitzpatrick, director of the Lab of Ornithology; and the legendary Ted Parker.

This would be a lightning-fast tour, five full days of hard-driving birding on a route most people take two or three weeks to cover. Still, I knew it would be well worth it. This was my first trip to South America, and almost every bird would be new to me. But the best part was that our group would be traveling with John O’Neill and visiting some of the very places where he had discovered new species of birds.

Most of the tour members arrived in Lima late on a Sunday night in September. I ran into our guide, Barry Walker, at the airport. Originally from Manchester, Walker is an expatriate Englishman who has lived in Peru for decades. Author of A Field Guide to the Birds of Machu Picchu and the Cuzco Area and Peruvian Wildlife: A Visitor’s Guide to the High Andes, Barry knows the area intimately and is a popular birding guide and owner of Manu Expeditions. He is also the British consul in Cuzco. But clad in baggy cargo pants with a sludge-colored birding vest and a sweat-stained leather hat, Walker seems more akin to Crocodile Dundee than to the stereotypical straitlaced British diplomat. His gregarious good humor and enthusiasm were infectious, and in the days ahead we willingly followed him through rugged mountains, parched desert habitats, and misty rainforests to look for birds.

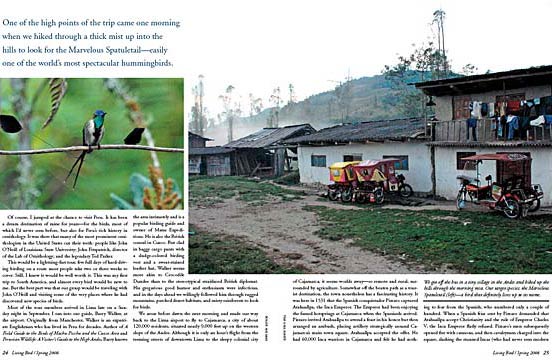

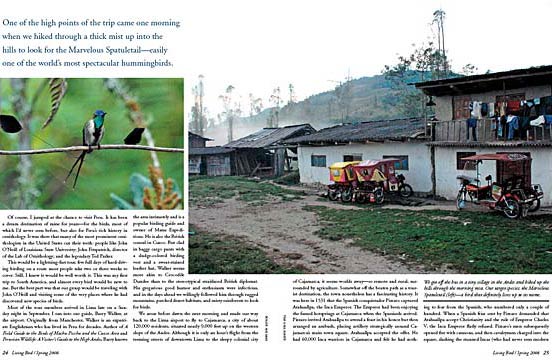

We arose before dawn the next morning and made our way back to the Lima airport to fly to Cajamarca, a city of about 120,000 residents, situated nearly 9,000 feet up on the western slope of the Andes. Although it is only an hour’s flight from the teeming streets of downtown Lima to the sleepy colonial city of Cajamarca, it seems worlds away—so remote and rural, surrounded by agriculture. Somewhat off the beaten path as a tourist destination, the town nonetheless has a fascinating history. It was here in 1531 that the Spanish conquistador Pizzaro captured Atahuallpa, the Inca Emperor. The Emperor had been enjoying the famed hotsprings at Cajamarca when the Spaniards arrived. Pizzaro invited Atahuallpa to attend a feast in his honor but then arranged an ambush, placing artillery strategically around Cajamarca’s main town square. Atahuallpa accepted the offer. He had 60,000 Inca warriors in Cajamarca and felt he had nothing to fear from the Spanish, who numbered only a couple of hundred. When a Spanish friar sent by Pizzaro demanded that Atahuallpa accept Christianity and the rule of Emperor Charles V, the Inca Emperor flatly refused. Pizzaro’s men subsequently opened fire with cannons, and then cavalrymen charged into the square, slashing the stunned Incas (who had never seen modern weaponry) with sabers from horseback. The battle was a complete rout, leaving some 7,000 Incas dead and their Emperor imprisoned.

Atahuallpa spent months locked in a room in Cajamarca as gold and silver were brought by the ton to Pizarro from throughout the Inca Empire to pay for his ransom. In the end, he was not released. Atahuallpa was executed by the Spanish on August 29, 1533, thus effectively ending 300 years of Inca rule in the area.

The Inca Baths, where Atahuallpa was bathing when the Spanish arrived, still remain, as does the “Ransom Room” where the Emperor was held prisoner and the town square, now called the Plaza de Armas (“Square of Weapons”). The people in Cajamarca tend to dress colorfully, the women in longish baggy skirts, often with a blanket wrapped around their shoulders, and many wear sombreros de paja—the traditional straw hats with a high, flat top.

Before we officially embarked on our birding journey, we were feted at a local resort, where a sumptuous brunch was served as a boy and girl performed a traditional Spanish dance and a rider with a high-stepping dark-brown horse pranced past. But most of us were too busy trying to watch the birds in the garden—such as the stunning long-tailed hummingbirds called Green-tailed Trainbearers—to give the performers the attention they deserved.

I sat with John O’Neill and his wife Letty and talked with him about his nearly lifelong infatuation with Peru. He spoke in a mild Texas drawl and seemed easygoing and friendly. His story is fascinating. In many ways, it was O’Neill who put Peru on the map birdwise. At the time he first visited the country in 1961, right after his freshman year at the University of Oklahoma, most people thought that the age of discovery in ornithology was long past.

“Birds are . . . the best studied of any class in the animal kingdom,” wrote Erwin Stresemann in 1951. “By now the number of bird species, and, for that matter, the number and distribution of the geographical races have been all but completely determined.” Peru proved him wrong—with a little help from John O’Neill.

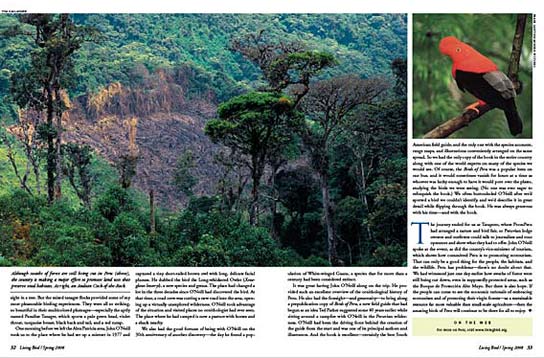

He returned to Peru many times after his initial trip. On his third visit, he was given several bird specimens that had been collected by Indians in the northern part of the country. One of them was a tanager unlike any he knew of, with a bright orange throat. The bird turned out not only to be a new species but a new genus as well—the Orange-throated Tanager (Wetmorethraupis sterrhopteron). So before he had even graduated from college, O’Neill had already described a bird that was previously unknown to science. And that was just the beginning. (To date, he has participated in describing 13 new species of birds and also finding many species that were not previously known to reside in Peru.)

Many more birders and ornithologists would follow in the late 1960s and ’70s in what would become a new age of discovery for Peruvian birds. Ted Parker, who made his first trip to Peru with John O’Neill in the early 1970s, became forever hooked and spent the rest of his life studying South American birds. (Ted died tragically at the age of 40 in a 1993 plane crash while working on an aerial bird survey in Ecuador.) John Fitzpatrick spent his formative years as a scientist studying Peruvian birds in the 1970s and himself described seven species of birds that were then unknown to science (see sidebar on page 30). Other prominent researchers who did pioneering fieldwork in Peru include Thomas S. Schulenberg, Douglas F. Stotz, and Daniel F. Lane, all of whom were coauthors with O’Neill of the recently released field guide, Birds of Peru; Gary Graves of the Smithsonian Institution; and Kenneth V. Rosenberg of the Lab of Ornithology.

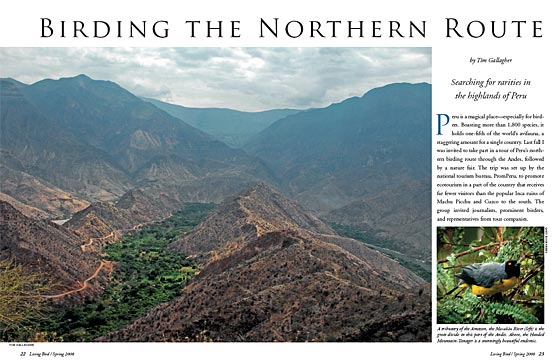

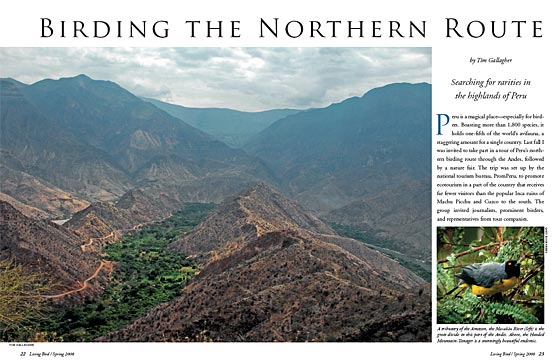

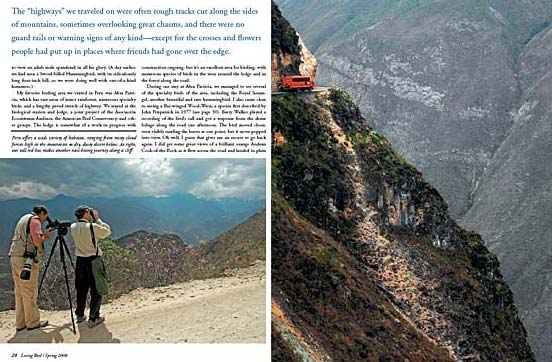

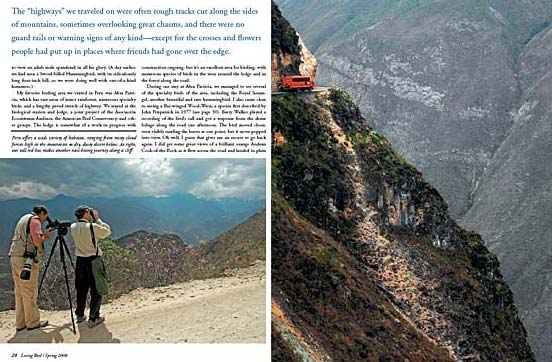

After lunch, we drove away in our tall, odd-looking red bus, heading eastward on a narrow dirt road. Paved roads would be a rarity for most of the rest of the trip. More often, the “highways” we traveled on were rough tracks cut along the sides of mountains, sometimes overlooking great chasms just inches from the bus’s tires, and there were no guard rails or warning signs of any kind—except for the crosses and flowers people had put up in places where friends or relatives had gone over the edge. And the tall, narrow design of our bright red tour bus only added to the queasy sense of uneasiness we all felt in the pit of our stomachs. Still, this is what adventure travel is all about, and we were rewarded with spectacular vistas at every turn, especially later as the great Marañón Basin opened up before us, wider than the Grand Canyon.

A tributary of the Amazon, the Marañón River is the great divide in this area. Driving into the valley, you descend rapidly, dropping from 10,000 feet above sea level to fewer than 3,000 feet at the river, and then back up to 10,000 on the other side. The change in habitats is astounding, with damp misty cloud forests on the higher elevations and desert habitats with cactuses below, in the rain shadow of the mountains, looking almost like Arizona in places. Over the millennia, distinctive species of birds have evolved on both sides of the divide as well as in the valley below, resulting in a staggering number of endemics.

As we dropped down to the river, shortly before crossing to the other side on a bridge, our bus hit a large rock and blew out a back tire, with a great boom that echoed across the canyon. Fortunately, we had dual tires in back, so we were able to limp along for a few miles to a place where we could get the outer left tire changed. The stop wasn’t wasted. We had a nice view of a Pearl Kite, which flew over the river, carrying a small prey item in its feet, and we also spotted a Peruvian Pigeon, an endemic species we had hoped to find.

One of the high points of the trip for me came one morning when we drove to Chachapoyas and hiked through a thick mist up into the hills to look for the Marvelous Spatuletail. To me, the spatuletail is easily the world’s most spectacular hummingbird. The adult male has a glittering blue crown and an emerald green gorget, but most remarkable are the bird’s two long, thin outer tail feathers tipped with large feathered racket shapes that sway in the breeze—the better to impress females. The species is a rare endemic, and we all desperately wanted to see one. We set ourselves up on a hillside overlooking an area of dense shrubbery that the birds were known to frequent, and trained our spotting scopes and binoculars on likely looking flowers. A beautiful vista opened up before us as the morning warmed up and the mist began to dissipate. Although we had to wait quite a while, we all got to view an adult male spatuletail in all his glory. (A day earlier, we had seen a Sword-billed Hummingbird, with its ridiculously long four-inch bill, so we were doing well with one-of-a-kind hummers.)

My favorite birding area we visited in Peru was Abra Patricia, which has vast areas of intact rainforest, numerous specialty birds, and a lengthy paved stretch of highway. We stayed at the biological station and lodge, a joint project of the Asociación Ecosistemas Andinos, the American Bird Conservancy, and other groups. The lodge is somewhat of a work in progress with construction ongoing, but it’s an excellent area for birding, with numerous species of birds in the trees around the lodge and in the forest along the road.

During our stay at Abra Patricia, we managed to see several of the specialty birds of the area, including the Royal Sunangel, another beautiful and rare hummingbird. I also came close to seeing a Bar-winged Wood-Wren, a species first described by John Fitzpatrick in 1977 (see Hooked on Peru). Barry Walker played a recording of the bird’s call and got a response from the dense foliage along the road one afternoon. The bird moved closer, even visibly rustling the leaves at one point, but it never popped into view. Oh well, I guess that gives me an excuse to go back again. I did get some great views of a brilliant orange Andean Cock-of-the-Rock as it flew across the road and landed in plain sight in a tree. But the mixed tanager flocks provided some of my most pleasurable birding experiences. They were all so striking, so beautiful in their multicolored plumages—especially the aptly named Paradise Tanager, which sports a pale green head, violet throat, turquoise breast, black back and tail, and a red rump.

One morning before we left the Abra Patricia area, John O’Neill took us to the place where he had set up a mistnet in 1977 and captured a tiny short-tailed brown owl with long, delicate facial plumes. He dubbed the bird the Long-whiskered Owlet (Xenoglaux loweryi), a new species and genus. The place had changed a lot in the three decades since O’Neill had discovered the bird. At that time, a road crew was cutting a new road into the area, opening up a virtually unexplored wilderness. O’Neill took advantage of the situation and visited places no ornithologist had ever seen. The place where he had camped is now a pasture with horses and a shack nearby.

We also had the good fortune of being with O’Neill on the 30th anniversary of another discovery—the day he found a population of White-winged Guans, a species that for more than a century had been considered extinct.

It was great having John O’Neill along on the trip. He provided such an excellent overview of the ornithological history of Peru. He also had the foresight—and generosity—to bring along a prepublication copy of Birds of Peru, a new field guide that had begun as an idea Ted Parker suggested some 40 years earlier while sitting around a campfire with O’Neill in the Peruvian wilderness. O’Neill had been the driving force behind the creation of the guide from the start and was one of its principal authors and illustrators. And the book is excellent—certainly the best South American field guide, and the only one with the species accounts, range maps, and illustrations conveniently arranged on the same spread. So we had the only copy of the book in the entire country along with one of the world experts on many of the species we would see. Of course, the Birds of Peru was a popular item on our bus, and it would sometimes vanish for hours at a time as whoever was lucky enough to have it would pore over the plates, studying the birds we were seeing. (No one was ever eager to relinquish the book.) We often buttonholed O’Neill after we’d spotted a bird we couldn’t identify, and we’d describe it in great detail while flipping through the book. He was always generous with his time—and with the book.

The journey ended for us at Tarapoto, where PromPeru had arranged a nature and bird fair, so Peruvian lodge owners and outfitters could talk to journalists and tour operators and show what they had to offer. John O’Neill spoke at the event, as did the county’s vice-minister of tourism, which shows how committed Peru is to promoting ecotourism. That can only be a good thing for the people, the habitats, and the wildlife. Peru has problems—there’s no doubt about that. We had witnessed just one day earlier how swaths of forest were still being cut down, even in supposedly protected areas, such as the Bosque de Protección Alto Mayo. But there is also hope. If the people can come to see the economic rationale of embracing ecotourism and of protecting their virgin forests—as a sustainable resource far more valuable than small-scale agriculture—then the amazing birds of Peru will continue to be there for all to enjoy.