Spirit of the North: the Common Loon

Text and photos by Marie Read April 15, 2008

Through the misty sunrise on a northern lake echoes a sound that stirs profound emotions in anyone who hears it: the haunting cry of the Common Loon. The loon symbolizes the wildness of the north—wildness that many of us, trapped in an ever-more-urbanized society, long for from the depths of our souls.

Since ancient times the loon has featured prominently in Native American mythology. In Sioux and Lakota legends it plays a role in recreating the post-diluvian world. An Ojibwa tale credits the loon’s voice as the inspiration for Native American flutes. And from Alaska, a Tsimshian story describes how a loon restores a blind man’s sight, for which it is rewarded with the gift of the beautiful necklace of white feathers adorning its neck.

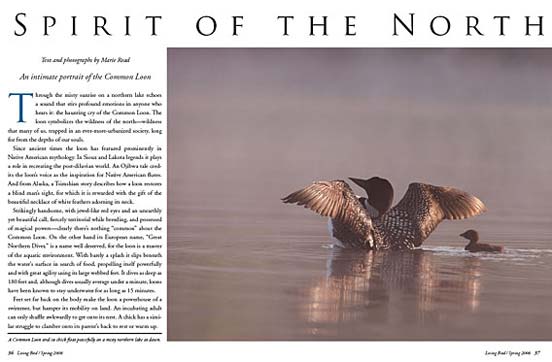

Strikingly handsome, with jewel-like red eyes and an unearthly yet beautiful call, fiercely territorial while breeding, and possessed of magical powers—clearly there’s nothing “common” about the Common Loon. On the other hand its European name, “Great Northern Diver,” is a name well deserved, for the loon is a master of the aquatic environment. With barely a splash it slips beneath the water’s surface in search of food, propelling itself powerfully and with great agility using its large webbed feet. It dives as deep as 180 feet and, although dives usually average under a minute, loons have been known to stay underwater for as long as 15 minutes.

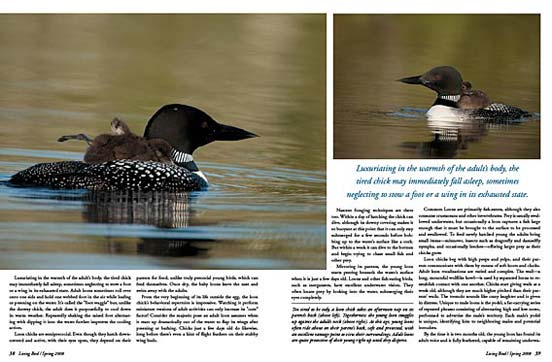

Feet set far back on the body make the loon a powerhouse of a swimmer, but hamper its mobility on land. An incubating adult can only shuffle awkwardly to get onto its nest. A chick has a similar struggle to clamber onto its parent’s back to rest or warm up.

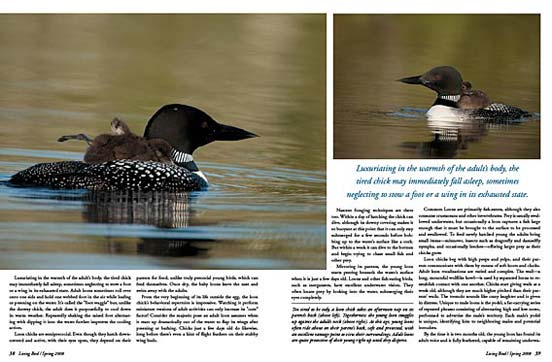

Luxuriating in the warmth of the adult’s body, the tired chick may immediately fall asleep, sometimes neglecting to stow a foot or a wing in its exhausted state. Adult loons sometimes roll over onto one side and hold one webbed foot in the air while loafing or preening on the water. It’s called the “foot waggle” but, unlike the drowsy chick, the adult does it purposefully, to cool down in warm weather. Repeatedly shaking the raised foot alternating with dipping it into the water further improves the cooling action.

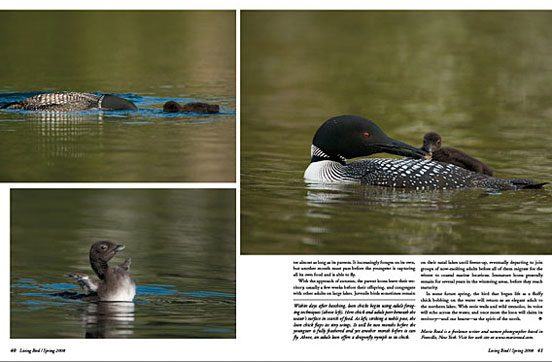

Loon chicks are semiprecocial. Even though they hatch down-covered and active, with their eyes open, they depend on their parents for food, unlike truly precocial young birds, which can feed themselves. Once dry, the baby loons leave the nest and swim away with the adults.

From the very beginning of its life outside the egg, the loon chick’s behavioral repertoire is impressive. Watching it perform miniature versions of adult activities can only increase its “cute” factor! Consider the majestic pose an adult loon assumes when it rears up dramatically out of the water to flap its wings after preening or bathing. Chicks just a few days old do likewise, long before there’s even a hint of flight feathers on their stubby wing buds.

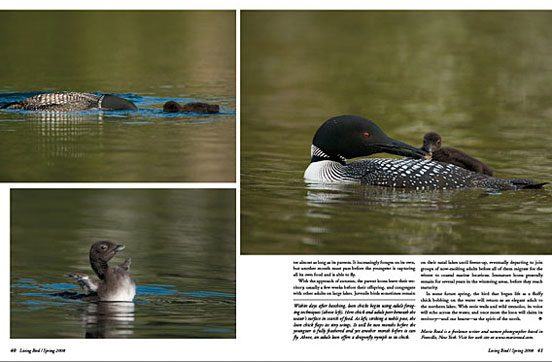

Nascent foraging techniques are there too. Within a day of hatching the chick can dive, although its downy covering makes it so buoyant at this point that it can only stay submerged for a few seconds before bobbing up to the water’s surface like a cork. But within a week it can dive to the bottom and begin trying to chase small fish and other prey.

Mirroring its parents, the young loon starts peering beneath the water’s surface when it is just a few days old. Loons and other fish-eating birds, such as mergansers, have excellent underwater vision. They often locate prey by looking into the water, submerging their eyes completely.

Common Loons are primarily fish-eaters, although they also consume crustaceans and other invertebrates. Prey is usually swallowed underwater, but occasionally a loon captures a fish large enough that it must be brought to the surface to be processed and swallowed. To feed newly hatched young the adults bring small items—minnows, insects such as dragonfly and damselfly nymphs, and occasionally leeches—offering larger prey as their chicks grow.

Loon chicks beg with high peeps and yelps, and their parents communicate with them by means of soft hoots and clucks. Adult loon vocalizations are varied and complex. The wail—a long, mournful wolflike howl—is used by separated loons to re-establish contact with one another. Chicks start giving wails at a week old, although they are much higher pitched than their parents’ wails. The tremolo sounds like crazy laughter and is given in distress. Unique to male loons is the yodel, a far-carrying series of repeated phrases consisting of alternating high and low notes, performed to advertise the male’s territory. Each male’s yodel is unique, identifying him to neighboring males and potential intruders.

By the time it is two months old, the young loon has found its adult voice and is fully feathered, capable of remaining underwater almost as long as its parents. It increasingly forages on its own, but another month must pass before the youngster is capturing all its own food and is able to fly.

With the approach of autumn, the parent loons leave their territory, usually a few weeks before their offspring, and congregate with other adults on large lakes. Juvenile birds sometimes remain on their natal lakes until freeze-up, eventually departing to join groups of now-molting adults before all of them migrate for the winter to coastal marine locations. Immature loons generally remain for several years in the wintering areas, before they reach maturity.

In some future spring, the bird that began life as a fluffy chick bobbing on the water will return as an elegant adult to the northern lakes. With eerie wails and wild tremolos, its voice will echo across the water, and once more the loon will claim its territory—and our hearts—as the spirit of the north.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you