The “Prairie Hens” of Illinois

By Andrew Beahrs July 15, 2008

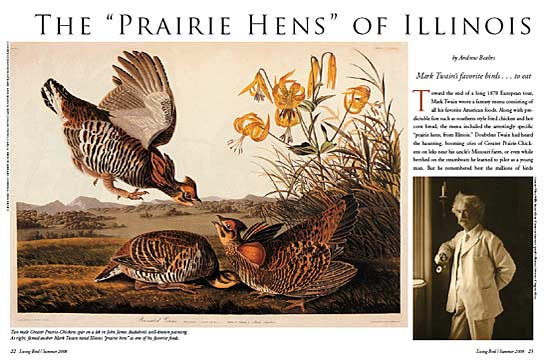

Toward the end of a long 1878 European tour, Mark Twain wrote a fantasy menu consisting of all his favorite American foods. Along with predictable fare such as southern-style fried chicken and hot corn bread, the menu included the arrestingly specific “prairie hens, from Illinois.” Doubtless Twain had heard the haunting, booming cries of Greater Prairie-Chickens on leks near his uncle’s Missouri farm, or even while berthed on the steamboats he learned to pilot as a young man. But he remembered best the millions of birds thriving in the Illinois prairies and cornfields just across the Mississippi River from his boyhood home. Today, Scott Simpson and the small but dedicated staff of the Prairie Ridge State Natural Area are working to preserve the last few hundred Greater Prairie-Chickens remaining in the state Twain associated most closely with them.

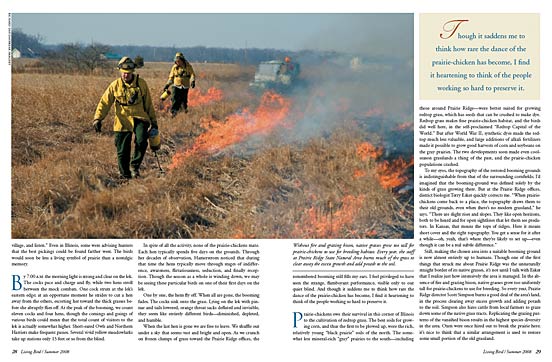

The story of prairie-chickens is inextricably tied to that of American grasslands. As I drive toward Prairie Ridge at 4:30 one frigid April morning, it’s easy to understand the birds’ near-disappearance: where could they find shelter among these vast, empty fields of corn stubble? But the landscape changes abruptly, as native grasses—brown, dry, dormant, but still strikingly wild—swell high and ragged alongside my headlights. Somewhere among them, I know, are the only prairie-chickens remaining in the state.

Soon I’m shivering, along with several dedicated birders and ornithology students, in a small plywood blind reserved several weeks in advance. The mating ground—also called a booming-ground, or lek—is immediately in front of us, perhaps 40 yards wide, a bit less than that deep. It was disked the previous autumn, and even by the spare moonlight I can see that its grass is short, as though mowed.

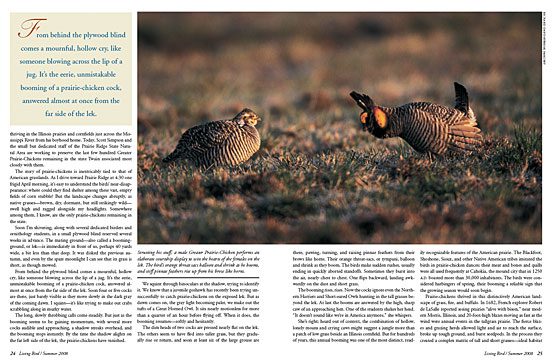

From behind the plywood blind comes a mournful, hollow cry, like someone blowing across the lip of a jug. It’s the eerie, unmistakable booming of a prairie-chicken cock, answered almost at once from the far side of the lek. Soon four or five cocks are there, just barely visible as they move slowly in the dark gray of the coming dawn. I squint—it’s like trying to make out crabs scrabbling along in murky water.

The long, slowly throbbing calls come steadily. But just as the booming seems to be gaining momentum, with several more cocks audible and approaching, a shadow streaks overhead, and the booming stops instantly. By the time the shadow alights on the far left side of the lek, the prairie-chickens have vanished.

We squint through binoculars at the shadow, trying to identify it. We know that a juvenile goshawk has recently been trying unsuccessfully to catch prairie-chickens on the exposed lek. But as dawn comes on, the gray light becoming paler, we make out the tufts of a Great Horned Owl. It sits nearly motionless for more than a quarter of an hour before flying off. When it does, the booming resumes—softly and hesitantly.

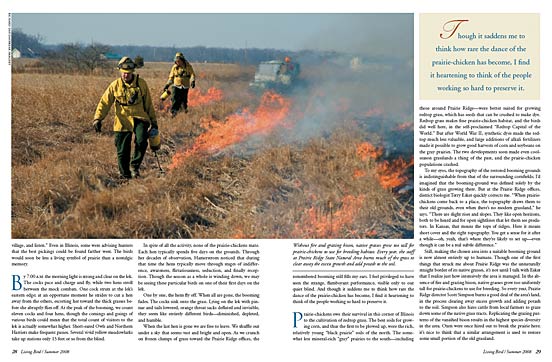

The dim heads of two cocks are pressed nearly flat on the lek. The others seem to have fled into taller grass, but they gradually rise or return, and soon at least six of the large grouse are there, pawing, turning, and raising pinnae feathers from their brows like horns. Their orange throat-sacs, or tympani, balloon and shrink as they boom. The birds make sudden rushes, usually ending in quickly aborted standoffs. Sometimes they burst into the air, nearly chest to chest. One flips backward, landing awkwardly on the dust and short grass.

The booming rises, rises. Now the cocks ignore even the Northern Harriers and Short-eared Owls hunting in the tall grasses beyond the lek. At last the booms are answered by the high, sharp caw of an approaching hen. One of the students shakes her head. “It doesn’t sound like we’re in America anymore,” she whispers.

She’s right; heard out of context, the combination of hollow, lonely moans and crying caws might suggest a jungle more than a patch of low grass beside an Illinois cornfield. But for hundreds of years, this annual booming was one of the most distinct, readily recognizable features of the American prairie. The Blackfoot, Shoshone, Sioux, and other Native American tribes imitated the birds in prairie-chicken dances; their meat and bones and quills were all used frequently at Cahokia, the mound city that in 1250 A.D. boasted more than 30,000 inhabitants. The birds were considered harbingers of spring, their booming a reliable sign that the growing season would soon begin.

Prairie-chickens thrived in this distinctively American landscape of grass, fire, and buffalo. In 1682, French explorer Robert de LaSalle reported seeing prairies “alive with bison,” near modern Morris, Illinois, and 20-foot-high blazes moving as fast as the wind were annual events in the tallgrass prairie. The fierce blazes and grazing herds allowed light and air to reach the surface, broke up tough ground, and burst seedpods. In the process they created a complex matrix of tall and short grasses—ideal habitat for the prairie-chickens. But by 1840, when Eliza R. Steele wrote of Illinois prairies as a “world of grass and flowers . . . animated with myriads of glittering birds and butterflies,” American settlers had already begun transforming the land by killing off bison and damping wildfires—and, most importantly of all, by plowing the prairie.

For decades, the incredibly tough roots of big bluestem and other grasses defied all plows but those drawn by powerful, and prohibitively expensive, teams of oxen. The 1833 invention of the steel plow, which broke the roots quickly and cheaply, finally led to the effective end of the Illinois prairie. But ironically, the destruction of the grasslands caused a short-term population explosion among the prairie-chickens that depended on them, because the patchwork of native grasses and croplands that accompanied the transition to agriculture provided an ideal combination of cover and food. By 1855, when 20-year-old Mark Twain was beginning his apprenticeship as a river pilot, the state prairie-chicken population was approaching an all-time peak, between 10 and 12 million birds.

By the time Twain traveled to Europe, where he would be tantalized by memories of roasted prairie hens, the birds were being hunted literally by the trainload. Chicago markets measured the birds by the cord and ton. More than 600,000 prairie-chickens were bought by the city’s markets every year, at a price of $3.75 per dozen. Frances Hamerstrom, who studied the birds in Wisconsin for decades, described the meat Twain longed for as rich and dark. In her memoir Strictly for the Chickens, she wrote that the birds should be “roasted for a short time in a hot oven and with the skin on” (she always resented having to give up most of the skins for use as research specimens). But many of the birds were prepared in fancier ways in restaurants as far away as New York’s renowned Delmonico’s, where chef Charles Ranhofer might jelly the breast meat before garnishing it with mushrooms, glazed truffles, and well-cooked cock’s-combs.

The birds were emblems of the time. Railroads ran specials for hunters. A monthly newspaper called The Prairie-Chicken declared itself “rich, spicy, popular, cheap, and wholesome” (and, the editors might have added, ominously transitory: the paper folded in a year). Market-hunting towns sprung up for the express purpose of providing the birds to urban sophisticates. They were carried to cities by modern refrigerator cars and served to people as far removed from their cries as typical modern Americans are from Nebraska feedlots. The prairie-chickens were being loved to death.

But what at last doomed prairie-chickens across most of their Illinois range was the very thing that had allowed their numbers to explode: the unsurpassed crops of corn that could be grown on broken prairies. By 1855, when Twain encountered an “untravelled native of the wilds of Illinois,” the “wilds” were well on their way to disappearing. The bare cornfields that replaced them provided no more winter cover than did the short, invasive, cool-season grasses that spread after farmers began damping down wildfires. The balance between native prairie and farmland that the birds had reveled in soon shifted decisively toward plowed fields.

As early as 1893, T. A. Bereman could write in Science that the birds he called “sun-worshippers” had undergone a steep decline in Iowa; he urged readers to wait for a spring morning when “the sun rises clear and the air is clear and frosty, [then] go out upon the suburbs of a prairie town, away from the usual noises of the village, and listen.” Even in Illinois, some were advising hunters that the best pickings could be found farther west. The birds would soon be less a living symbol of prairie than a nostalgic memory.

By 7:00 A.M. the morning light is strong and clear on the lek. The cocks pace and charge and fly, while two hens stroll between the mock combats. One cock struts at the lek’s eastern edge; at an opportune moment he strides to cut a hen away from the others, escorting her toward the thick grasses before she abruptly flies off. At the peak of the booming, we count eleven cocks and four hens, though the comings and goings of various birds could mean that the total count of visitors to the lek is actually somewhat higher. Short-eared Owls and Northern Harriers make frequent passes. Several vivid yellow meadowlarks take up stations only 15 feet or so from the blind.

In spite of all the activity, none of the prairie-chickens mate. Each hen typically spends five days on the grounds. Through her decades of observation, Hamerstrom noticed that during that time the hens typically move through stages of indifference, awareness, flirtatiousness, seduction, and finally reception. Though the season as a whole is winding down, we may be seeing these particular birds on one of their first days on the lek.

One by one, the hens fly off. When all are gone, the booming fades. The cocks sink onto the grass. Lying on the lek with pinnae and tails lowered, orange throat sacks deflated and invisible, they seem like entirely different birds—diminished, depleted, and humble.

When the last hen is gone we are free to leave. We shuffle out under a sky that seems vast and bright and open. As we crunch on frozen clumps of grass toward the Prairie Ridge offices, the remembered booming still fills my ears. I feel privileged to have seen the strange, flamboyant performance, visible only to our quiet blind. And though it saddens me to think how rare the dance of the prairie-chicken has become, I find it heartening to think of the people working so hard to preserve it.

Prairie-chickens owe their survival in this corner of Illinois to the cultivation of redtop grass. The best soils for growing corn, and thus the first to be plowed up, were the rich, relatively young “black prairie” soils of the north. The somewhat less mineral-rich “gray” prairies to the south—including those around Prairie Ridge—were better suited for growing redtop grass, which has seeds that can be crushed to make dye. Redtop grass makes fine prairie-chicken habitat, and the birds did well here, in the self-proclaimed “Redtop Capital of the World.” But after World War II, synthetic dyes made the redtop much less valuable, and large additions of alkali fertilizers made it possible to grow good harvests of corn and soybeans on the gray prairies. The two developments soon made even cool-season grasslands a thing of the past, and the prairie-chicken populations crashed.

To my eyes, the topography of the restored booming grounds is indistinguishable from that of the surrounding cornfields; I’d imagined that the booming-ground was defined solely by the kinds of grass growing there. But at the Prairie Ridge offices, district biologist Terry Esker quickly corrects me. “When prairie-chickens come back to a place, the topography draws them to their old grounds, even when there’s no modern grassland,” he says. “There are slight rises and slopes. They like open horizons, both to be heard and for open sightlines that let them see predators. In Kansas, that means the tops of ridges. Here it means short cover and the right topography. You get a sense for it after a while—oh, yeah, that’s where they’re likely to set up—even though it can be a real subtle difference.”

Still, making the chosen area into a suitable booming ground is now almost entirely up to humans. Though one of the first things that struck me about Prairie Ridge was the unnaturally straight border of its native grasses, it’s not until I talk with Esker that I realize just how intensively the area is managed. In the absence of fire and grazing bison, native grasses grow too uniformly tall for prairie-chickens to use for breeding. So every year, Prairie Ridge director Scott Simpson burns a good deal of the area’s land, in the process clearing away excess growth and adding potash to the soil. Simpson also hires cattle from local farmers to graze down some of the native grass tracts. Replicating the grazing patterns of the vanished bison results in the highest species diversity in the area. Oxen were once hired out to break the prairie here; it’s nice to think that a similar arrangement is used to restore some small portion of the old grassland.

Though the jobs of burning and grazing are complicated by the fact that Prairie Ridge’s 3,800 acres are broken into around a dozen unevenly sized tracts, all separated by private land, these divisions also allow for a complicated blend of habitats that make the area an invaluable refuge for grassland species. Esker points out that preserving natural, or even restored, prairie was never the ultimate goal here—as the peak numbers of prairie-chickens in the 1850s showed, a varied matrix of native grasses and croplands can support a higher population than an entirely natural ecosystem. So Simpson and his staff burn and graze, rip out fences and buildings to improve sightlines, and clear brush to cut down on predators. The result is a broken mosaic of remnant prairie, non-native grasses, wetlands, old pasture fields, and woods. Today, only about a quarter of the area is seeded with native grasses; if prairie-chickens prefer invasive cool-season grasses to native species during certain times of the year, the staff is more than happy to accommodate them.

In the early 1990s, Simpson says, surveys began showing a lack of egg success and fertility, both classic signs of a lack of genetic diversity. After a mere 46 birds were counted in 1994, the problem of a small gene pool appeared acute. Though hens can disperse over wide distances—one radio-collared bird made its way to the Marion County unit of Prairie Ridge, more than 50 miles away—it is not realistic to expect them to transverse 300 miles of cropland to mate with the prairie-chickens farther west.

The solution was to release birds trapped in Minnesota and Kansas, where large grasslands and solid conservation programs have helped to maintain solid prairie-chicken populations. The researchers hope that the addition of these birds will help to mimic some of the more organic genetic mixing once created through natural dispersal.

The result of the careful management is something close to the prairie-chicken ideal. There is a lek with short grasses and good sightlines, surrounded by taller grasses that give good brood cover, and, after the eggs hatch in May or June, a ready supply of insects. Surrounding cornfields provide waste grain after the harvest, and carefully selected birds from out of state help to mimic the natural migration of a larger population.

Admittedly, the small amount of available land is a lasting problem, one without a simple solution, as the advent of ethanol makes it increasingly expensive to acquire more land. The reality is that there are now probably about as many prairie-chickens in Illinois as there will ever be again. But thanks to the dedicated efforts of researchers at Prairie Ridge, the birds can go on booming, heralding spring with cries as haunting to listeners today as they once were to Mark Twain.

Andrew Beahrs is a freelance writer and novelist based in Berkeley, California. Visit his website at www.andrewbeahrs.com.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you