Birding California’s Central Coast

Text and photos by Brian Sullivan, co-project leader of eBird July 15, 2008

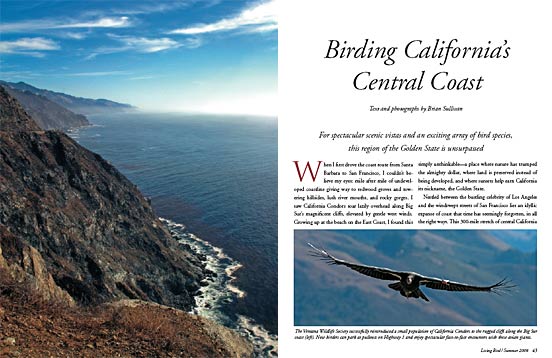

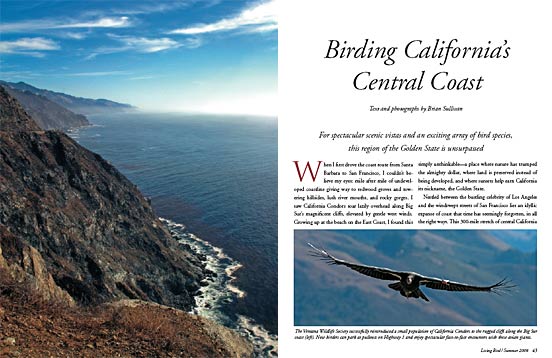

When I first drove the coast route from Santa Barbara to San Francisco, I couldn’t believe my eyes: mile after mile of undeveloped coastline giving way to redwood groves and towering hillsides, lush river mouths, and rocky gorges. I saw California Condors soar lazily overhead along Big Sur’s magnificent cliffs, elevated by gentle west winds. Growing up at the beach on the East Coast, I found this simply unthinkable—a place where nature has trumped the almighty dollar, where land is preserved instead of being developed, and where sunsets help earn California its nickname, the Golden State.

Nestled between the bustling celebrity of Los Angeles and the windswept streets of San Francisco lies an idyllic expanse of coast that time has seemingly forgotten, in all the right ways. This 300-mile stretch of central California is perhaps the most scenic coast in the United States. Many people visit this area simply to make the famous drive along Highway 1 in Big Sur, but there is much more to this area than scenic beauty. The region’s storied past is rich, spanning our imaginations from Zorro to Steinbeck, from Spanish missionaries to Russian fur-traders, from Cannery Row to fine wineries. Its biodiversity is no less complex. Hosting a remarkable variety of birds, Monterey is one of the most bird-rich counties in the United States, with 489 species recorded so far, and it provides some of the finest pelagic birding in North America.

Monterey Bay

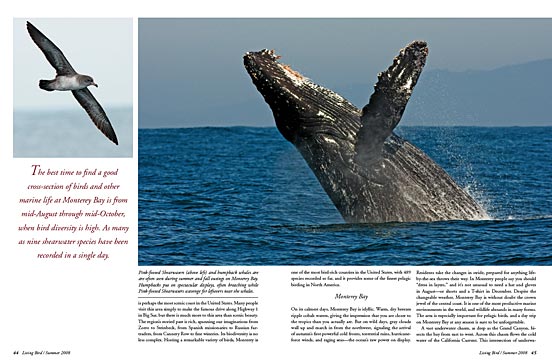

On its calmest days, Monterey Bay is idyllic. Warm, dry breezes ripple cobalt waters, giving the impression that you are closer to the tropics than you actually are. But on wild days, gray clouds wall up and march in from the northwest, signaling the arrival of autumn’s first powerful cold fronts, torrential rains, hurricane-force winds, and raging seas—the ocean’s raw power on display. Residents take the changes in stride, prepared for anything life-by-the-sea throws their way. In Monterey people say you should “dress in layers,” and it’s not unusual to need a hat and gloves in August—or shorts and a T-shirt in December. Despite the changeable weather, Monterey Bay is without doubt the crown jewel of the central coast. It is one of the most productive marine environments in the world, and wildlife abounds in many forms. The area is especially important for pelagic birds, and a day trip on Monterey Bay at any season is sure to be unforgettable.

A vast underwater chasm, as deep as the Grand Canyon, bisects the bay from east to west. Across this chasm flows the cold water of the California Current. This intersection of underwater topography and flowing water creates a phenomenon called upwelling, which brings nutrient-rich sediment and cold water close to the surface, creating a remarkable food source for marine life. Whales, seabirds, marine mammals, and a host of fish share this resource, creating a unique and spectacular ecosystem.

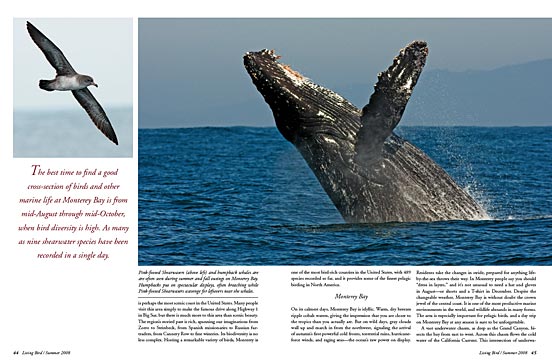

In summer, hundreds of thousands of Sooty Shearwaters use the bay as a staging ground. They hold the record for the world’s longest bird migration, leaving their nesting colonies off New Zealand and traversing the entire Pacific Ocean in a figure-eight pattern. After arriving in the bay, they feast on the abundant resources while they molt their feathers and prepare for the nearly 20,000-mile journey home. On midsummer days when the west wind blows, the beach can be littered with the feathers of Sooty Shearwaters, as swarms of the birds feed offshore.

The marine mammal show in the bay is no less spectacular. Gray, humpback, blue, and fin whales all converge on Monterey Bay during different times of the year. Orcas prowl the area year-round, and numerous dolphins and porpoises are easy to find offshore. The best time to find a good cross-section of birds and other marine life at Monterey Bay is from mid-August through mid-October, when bird diversity is high. As many as nine shearwater species have been recorded in a single day.

Coastal Estuaries

The central coast of California is dotted with several important coastal estuaries. Among the finest are Morro Bay and Elkhorn Slough. At low tide, broad expanses of mud flats become available for feeding, and these areas are packed with migrant and wintering shorebirds and waterfowl. A typical afternoon at either location often reveals tens of thousands of birds, ranging from Marbled Godwits and Western Sandpipers to Brant and Western Grebes. A kayak is an excellent way to view wildlife at either location.

You can find a large concentration of sea otters at Elkhorn Slough in Moss Landing most afternoons—as many as 75 of them congregate inside the breakwater, out of the rough ocean swell, to sleep and relax. The otters, which are spectacular enough, are joined by large numbers of harbor seals and California sea lions. Locals and visitors alike are well aware of how special these coastal estuaries are.

Rocky Shore

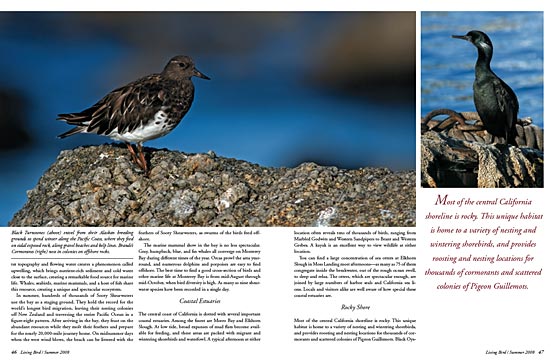

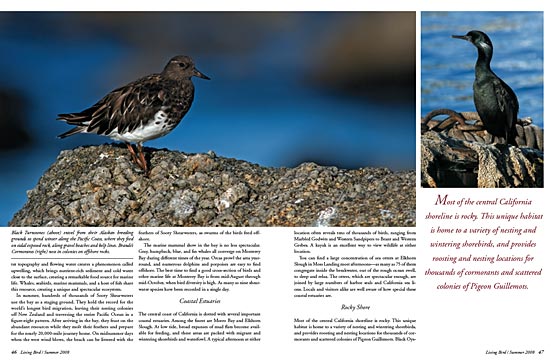

Most of the central California shoreline is rocky. This unique habitat is home to a variety of nesting and wintering shorebirds, and provides roosting and nesting locations for thousands of cormorants and scattered colonies of Pigeon Guillemots. Black Oystercatchers, which pry small mollusks off the rocks and adeptly open them with their chisel-like bills, are a representative bird of this habitat. They have one of the longest and narrowest ranges of any bird in the world, breeding from the Alaska Peninsula south through northern Baja California, but they typically aren’t found more than a few hundred meters from the shoreline. In addition to the resident Black Oystercatchers, these areas are favored by wintering shorebirds such as Black Turnstones and Surfbirds.

Big Sur

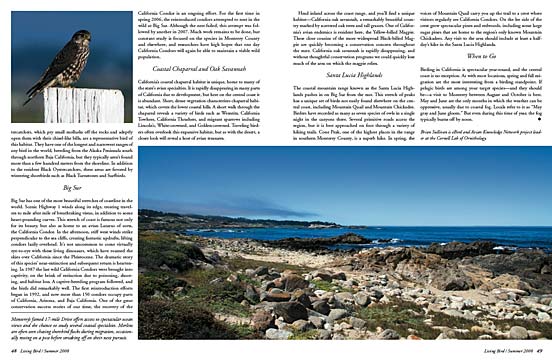

Big Sur has one of the most beautiful stretches of coastline in the world. Scenic Highway 1 winds along its edge, treating travelers to mile after mile of breathtaking vistas, in addition to some heart-pounding curves. This stretch of coast is famous not only for its beauty, but also as home to an avian Lazarus of sorts, the California Condor. In the afternoon, stiff west winds strike perpendicular to the sea cliffs, creating fantastic updrafts, lifting condors lazily overhead. It’s not uncommon to come virtually eye-to-eye with these living dinosaurs, which have roamed the skies over California since the Pleistocene. The dramatic story of this species’ near-extinction and subsequent return is heartening. In 1987 the last wild California Condors were brought into captivity, on the brink of extinction due to poisoning, shooting, and habitat loss. A captive-breeding program followed, and the birds did remarkably well. The first reintroduction efforts began in 1992, and now more than 150 condors occupy parts of California, Arizona, and Baja California. One of the great conservation success stories of our time, the recovery of the California Condor is an ongoing effort. For the first time in spring 2006, the reintroduced condors attempted to nest in the wild at Big Sur. Although the nest failed, this attempt was followed by another in 2007. Much work remains to be done, but constant study is focused on the species in Monterey County and elsewhere, and researchers have high hopes that one day California Condors will again be able to maintain a viable wild population.

Coastal Chaparral and Oak Savannah

California’s coastal chaparral habitat is unique, home to many of the state’s avian specialties. It is rapidly disappearing in many parts of California due to development, but here on the central coast it is abundant. Short, dense vegetation characterizes chaparral habitat, which covers the lower coastal hills. A short walk through the chaparral reveals a variety of birds such as Wrentits, California Towhees, California Thrashers, and migrant sparrows including Lincoln’s, White-crowned, and Golden-crowned. Traveling birders often overlook this expansive habitat, but as with the desert, a closer look will reveal a host of avian treasures.

Head inland across the coast range, and you’ll find a unique habitat—California oak savannah, a remarkably beautiful country marked by scattered oak trees and tall grasses. One of California’s avian endemics is resident here, the Yellow-billed Magpie. These close cousins of the more widespread Black-billed Magpie are quickly becoming a conservation concern throughout the state. California oak savannah is rapidly disappearing, and without thoughtful conservation programs we could quickly lose much of the area on which the magpie relies.

Santa Lucia Highlands

The coastal mountain range known as the Santa Lucia Highlands pushes in on Big Sur from the east. This stretch of peaks has a unique set of birds not easily found elsewhere on the central coast, including Mountain Quail and Mountain Chickadee. Birders have recorded as many as seven species of owls in a single night in the canyons there. Several primitive roads access the region, but it is best approached on foot through a variety of hiking trails. Cone Peak, one of the highest places in the range in southern Monterey County, is a superb hike. In spring, the voices of Mountain Quail carry you up the trail to a crest where visitors regularly see California Condors. On the lee side of the crest grow spectacular pines and redwoods, including some large sugar pines that are home to the region’s only known Mountain Chickadees. Any visit to the area should include at least a half-day’s hike in the Santa Lucia Highlands.

When to Go

Birding in California is spectacular year-round, and the central coast is no exception. As with most locations, spring and fall migration are the most interesting from a birding standpoint. If pelagic birds are among your target species—and they should be—a visit to Monterey between August and October is best. May and June are the only months in which the weather can be oppressive, usually due to coastal fog. Locals refer to it as “May gray and June gloom.” But even during this time of year, the fog typically burns off by noon.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you