The Deal of the Century? Conserving California’s Tejon Ranch

By Gary Langham October 15, 2008

A controversial agreement between the Tejon Ranch Company and five environmental organizations may be the last best hope for saving an irreplaceable wilderness in California

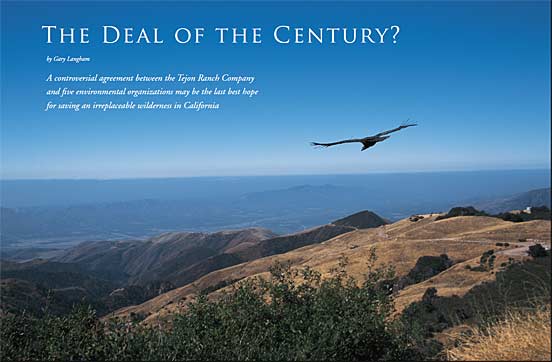

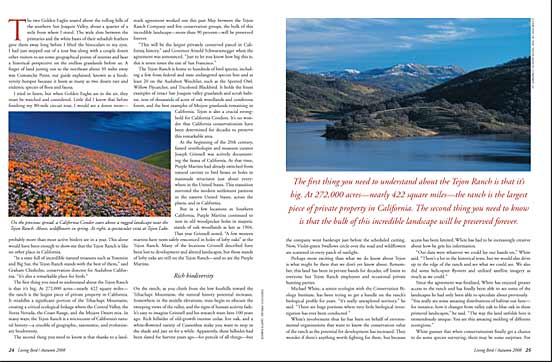

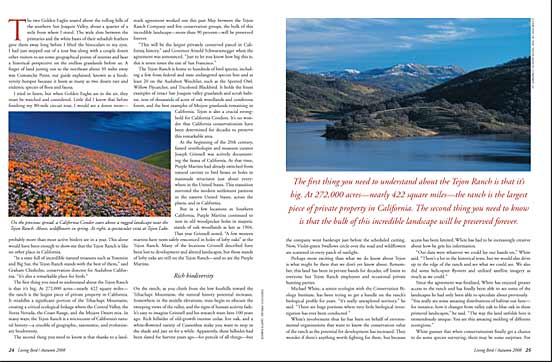

The two Golden Eagles soared above the rolling hills of the southern San Joaquin Valley, about a quarter of a mile from where I stood. The wide slots between the primaries and the white bases of their subadult feathers gave them away long before I lifted the binoculars to my eyes. I had just stepped out of a tour bus along with a couple dozen other visitors to see some geographical points of interest and hear a historical perspective on the endless grasslands before us. A finger of land jutting out to the northeast about 50 miles away was Comanche Point, our guide explained, known as a biodiversity hotspot because it hosts as many as two dozen rare and endemic species of flora and fauna.

I tried to listen, but when Golden Eagles are in the air, they must be watched and considered. Little did I know that before finishing my 80-mile circuit tour, I would see a dozen more—probably more than most active birders see in a year. This alone would have been enough to show me that the Tejon Ranch is like no other place in California.

“In a state full of incredible natural treasures such as Yosemite and Big Sur, the Tejon Ranch stands with the best of them,” said Graham Chisholm, conservation director for Audubon California. “It’s also a remarkable place for birds.”

The first thing you need to understand about the Tejon Ranch is that it’s big. At 272,000 acres—nearly 422 square miles—the ranch is the largest piece of private property in California. It straddles a significant portion of the Tehachapi Mountains, creating a critical ecological linkage where the Central Valley, the Sierra Nevada, the Coast Range, and the Mojave Desert mix. In many ways, the Tejon Ranch is a microcosm of California’s natural history—a crucible of geographic, taxonomic, and evolutionary biodiversity.

The second thing you need to know is that thanks to a landmark agreement worked out this past May between the Tejon Ranch Company and five conservation groups, the bulk of this incredible landscape—more than 90 percent—will be preserved forever.

“This will be the largest privately conserved parcel in California history,” said Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger when the agreement was announced. “Just to let you know how big this is, this is seven times the size of San Francisco.”

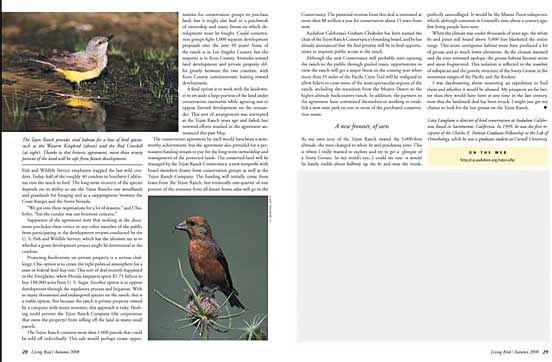

The Tejon Ranch is home to hundreds of bird species, including a few from federal and state endangered species lists and at least 20 on the Audubon Watchlist, such as the Spotted Owl, Willow Flycatcher, and Tricolored Blackbird. It holds the finest examples of intact San Joaquin valley grasslands and scrub habitat, tens of thousands of acres of oak woodlands and coniferous forest, and the best examples of Mojave grasslands remaining in California. Tejon is also a crucial stronghold for California Condors. It’s no wonder that California conservationists have been determined for decades to preserve this remarkable area.

At the beginning of the 20th century, famed ornithologist and museum curator Joseph Grinnell was actively documenting the fauna of California. At that time, Purple Martins had already switched from natural cavities to bird boxes or holes in manmade structures just about everywhere in the United States. This transition mirrored the modern settlement patterns in the eastern United States, across the plains, and in California.

But in a few locations in Southern California, Purple Martins continued to nest in old woodpecker holes in majestic stands of oak woodlands as late as 1904. That year Grinnell noted, “A few western martins have nests safely ensconced in holes of lofty oaks” at the Tejon Ranch. Many of the locations Grinnell described have been lost to development and altered landscapes, but those stands of lofty oaks are still on the Tejon Ranch—and so are the Purple Martins.

Rich biodiversity

On the ranch, as you climb from the low foothills toward the Tehachapi Mountains, the natural history potential increases. Somewhere in the middle elevations, trees begin to obscure the sweeping views of the valley, and the signs of human activity fade. It’s easy to imagine Grinnell and his research team here 100 years ago. Rich hillsides of old-growth incense cedar, live oak, and a white-flowered variety of Ceanothus make you want to stop in the shade and just sit for a while. Apparently, these hillsides had been slated for harvest years ago—for pencils of all things—but the company went bankrupt just before the scheduled cutting. Now, Violet-green Swallows circle over the road and wildflowers are scattered in every patch of sunlight.

Perhaps more exciting than what we do know about Tejon is what might be there that we don’t yet know about. Remember, this land has been in private hands for decades, off limits to everyone but Tejon Ranch employees and occasional private hunting parties.

Michael White, a senior ecologist with the Conservation Biology Institute, has been trying to get a handle on the ranch’s biological profile for years. “It’s really unexplored territory,” he said. “There are huge portions where very little biological investigation has ever been conducted.”

White’s involvement thus far has been on behalf of environmental organizations that want to know the conservation value of the ranch as the potential for development has increased. They wonder if there’s anything worth fighting for there, but because access has been limited, White has had to be increasingly creative about how he gets his information.

“Our data were whatever we could lay our hands on,” White said. “There’s a lot in the historical texts, but we would also drive up to the edge of the ranch and see what we could see. We also did some helicopter flyovers and utilized satellite imagery as much as we could.”

Since the agreement was finalized, White has enjoyed greater access to the ranch and has finally been able to see some of the landscapes he had only been able to speculate about previously.

“You really see some amazing distributions of habitat out here—for instance, how it changes from valley oak to blue oak in these primeval landscapes,” he said. “The way the land unfolds here is tremendously unique. You see this amazing melding of different ecoregions.”

White guesses that when conservationists finally get a chance to do some species surveying, there may be some surprises. For instance, given the amount of virgin fir forest on the ranch, he wouldn’t be surprised to find some Sooty Grouse, a species many biologists believe has been extirpated from Southern California. “If they were to be in this region, this would be the place, and I can’t imagine when people might have last looked for them on Tejon.”

But they’ll get their chance now, because the conservation agreement contains a number of provisions for public access to this landscape.

“Our agreement provides for unparalleled conservation and increased public access, all of which means birders will eventually have the opportunity to enjoy the natural beauty of Tejon Ranch while identifying the many bird species found here,” said Bob Stine, president and CEO of the Tejon Ranch Company.

The agreement

The Tejon Ranch conservation agreement locks in the protection of 178,000 acres, with an option to purchase another 62,000 acres during the next three years, and opens the land to the public for the first time. At the same time, with the deal in hand, the Tejon Ranch Company will now seek to develop about 10 percent of the ranch along the Interstate 5 corridor, including a planned community of 23,000 homes in Los Angeles County and a posh resort community in the mountains.

Negotiations on the agreement took nearly two years. On the conservation side were Audubon California, the Sierra Club, the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Endangered Habitats League, and the Planning and Conservation League.

For the conservation groups, the negotiations presented a unique opportunity to settle the ranch’s future and avoid decades of piecemeal legal wrangling with little likelihood of gaining the extensive habitat protection and funding for long-term restoration and management that this agreement represents.

“Of course, no development at all would have been preferable,” said Audubon California’s Graham Chisholm, who played a major role in the negotiations. “But all you have to do is look around Kern and Los Angeles counties and see what is happening on privately held land to understand that that outcome is just wishful thinking. To commit ourselves to years of fighting for that pipe dream would have been irresponsible gambling with California’s most biologically diverse property.”

Although the agreement is supported by most of the major conservation players in California, some conservationists feel that the agreement falls short of the complete protection that this land warrants.

“We know that the environmental groups who have negotiated the accord did so with the best of intentions, but we could not sign off on this highly flawed agreement,” said Peter Galvin, conservation director at the Center for Biological Diversity. “Virtually all of the areas to be acquired or managed under the conservation easement are undevelopable anyway.”

Critics of the agreement have also taken issue with the fact that the conservation groups have agreed not to oppose development in certain areas that are considered critical habitat for the California Condor. The Tejon Ranch has long been recognized as an important foraging site for California Condors, one of the word’s rarest birds. Although the species is also found in Arizona and Mexico, thanks to an aggressive captive-breeding and release program, the condor is a distinct part of California’s natural heritage, so much so that it was recently included on the state’s U.S. quarter. Down to just 23 birds in the world in the 1980s, captive breeding brought the species back from the brink of extinction to more than 300 today.

Audubon condor biologists worked on the ranch in the 1960s, and it was on the Tejon Ranch in 1987 that Audubon and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employees trapped the last wild condors. Today, half of the roughly 40 condors in Southern California visit the ranch to feed. The long-term recovery of the species depends on its ability to use the Tejon Ranch’s vast woodlands and grasslands for foraging and as a steppingstone between the Coast Ranges and the Sierra Nevada.

“We got into these negotiations for a lot of reasons,” said Chis-holm, “but the condor was our foremost concern.”

Supporters of the agreement note that nothing in the document precludes these critics or any other member of the public from participating in the development reviews conducted by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which has the ultimate say as to whether a given development project might be detrimental to the condors.

Protecting biodiversity on private property is a serious challenge. One option is to create the right political atmosphere for a state or federal land buy-out. This sort of deal recently happened in the Everglades, when Florida taxpayers spent $1.75 billion to buy 188,000 acres from U. S. Sugar. Another option is to oppose development through the regulatory process and litigation. With so many threatened and endangered species on the ranch, this is a viable option. But because the ranch is private property owned by a company with many investors, this approach is risky. Nothing could prevent the Tejon Ranch Company (the corporation that owns the property) from selling off the land in many small parcels.

The Tejon Ranch contains more than 1,000 parcels that could be sold off individually. This sale would perhaps create opportunities for conservation groups to purchase land, but it might also lead to a patchwork of ownership and many fronts on which development must be fought. Could conservation groups fight 1,000 separate development proposals over the next 50 years? Some of the ranch is in Los Angeles County, but the majority is in Kern County. Attitudes toward land development and private property differ greatly between the two counties, with Kern County commissioners leaning toward development.

A final option is to work with the landowner to set aside a large portion of the land under conservation easements while agreeing not to oppose limited development on the remainder. This sort of arrangement was attempted at the Tejon Ranch years ago and failed, but renewed efforts resulted in the agreement announced this past May.

The conservation agreement by itself would have been a noteworthy achievement, but the agreement also provided for a permanent funding stream to pay for the long-term stewardship and management of the protected lands. The conserved land will be managed by the Tejon Ranch Conservancy, a new nonprofit with board members drawn from conservation groups as well as the Tejon Ranch Company. The funding will initially come from loans from the Tejon Ranch, but eventually one-quarter of one percent of the revenues from all future home sales will go to the Conservancy. The potential revenue from this deal is estimated at more than $8 million a year for conservation about 15 years from now.

Audubon California’s Graham Chisholm has been named the chair of the Tejon Ranch Conservancy’s founding board, and he has already announced that the first priority will be to find opportunities to improve public access to the ranch.

Although the new Conservancy will probably start opening the ranch to the public through guided tours, opportunities to view the ranch will get a major boost in the coming year when more than 35 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail will be realigned to allow hikers to cross some of the most spectacular regions of the ranch, including the transition from the Mojave Desert to the higher-altitude backcountry ranch. In addition, the partners to the agreement have committed themselves to working to establish a new state park on one or more of the purchased conservation zones.

A new frontier, of sorts

As my own tour of the Tejon Ranch neared the 5,000-foot altitude, the trees changed to white fir and ponderosa pine. This is where I really wanted to explore and try to get a glimpse of a Sooty Grouse. In my mind’s eye, I could see one: it would be barely visible about halfway up the fir and near the trunk, perfectly camouflaged. It would be the Mount Pinos subspecies, which, although common in Grinnell’s time about a century ago, few living people have seen.

When the climate was cooler thousands of years ago, the white fir and pines still found above 5,000 feet blanketed the entire range. This more contiguous habitat must have produced a lot of grouse and at much lower elevations. As the climate warmed and the trees retreated upslope, the grouse habitat became more and more fragmented. This isolation is reflected in the number of subspecies and the genetic structure of the Sooty Grouse in the mountain ranges of the Pacific and the Rockies.

I was daydreaming about mounting an expedition to find them and whether it would be allowed. My prospects are far better than they would have been at any time in the last century, now that the landmark deal has been struck. I might just get my chance to look for the lost grouse on the Tejon Ranch.

Gary Langham is director of bird conservation at Audubon California, based in Sacramento, California. In 1999, he was the first recipient of the Charles E. Treman Graduate Fellowship at the Lab of Ornithology, while he was a graduate student at Cornell University.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you