Dr. Orbell’s Unlikely Quest: New Zealand’s Bush Moa

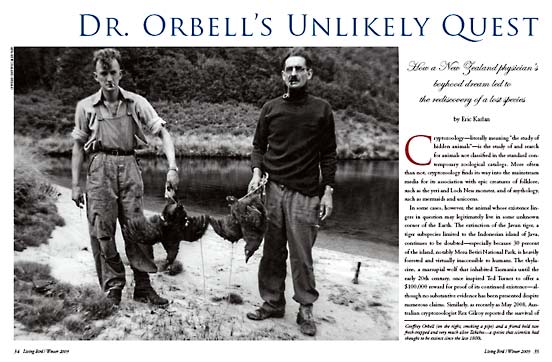

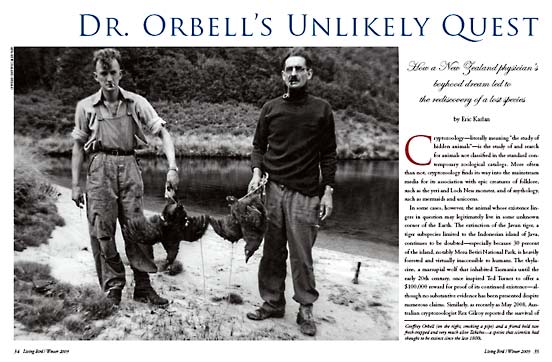

By Eric Karlan January 15, 2009

How a New Zealand physician’s boyhood dream led to the rediscovery of a lost species

Cryptozoology—literally meaning “the study of hidden animals”—is the study of and search for animals not classified in the standard contemporary zoological catalogs. More often than not, cryptozoology finds its way into the mainstream media for its association with epic creatures of folklore, such as the yeti and Loch Ness monster, and of mythology, such as mermaids and unicorns.

In some cases, however, the animal whose existence lingers in question may legitimately live in some unknown corner of the Earth. The extinction of the Javan tiger, a tiger subspecies limited to the Indonesian island of Java, continues to be doubted—especially because 30 percent of the island, notably Meru Betiri National Park, is heavily forested and virtually inaccessible to humans. The thylacine, a marsupial wolf that inhabited Tasmania until the early 20th century, once inspired Ted Turner to offer a $100,000 reward for proof of its continued existence—although no substantive evidence has been presented despite numerous claims. Similarly, as recently as May 2008, Australian cryptozoologist Rex Gilroy reported the survival of the Bush Moa (a supposedly extinct species of New Zealand bird that stood four feet tall) in dense bush near Hawke’s Bay, though the sighting has not been confirmed.

Although fantastic quests to find legendary animals give cryptozoologists as a whole a reputation for illegitimacy in the mainstream scientific community, there are many whose unwavering disbelief in the extinction of a species results in strategic searches for irrefutable cold, hard evidence. Success stories are rare, but any man, woman, or child set on rediscovering a Dodo or a dinosaur can find hope in the story of Geoffrey Orbell.

“On a beach at the bottom end of the lake we found fresh bird tracks,” said Orbell. “They were large enough for us to be quite certain that they were the tracks I had dreamed about . . . I measured the tracks as carefully as possible by scratching marks on the stem of my pipe—which is practically always in my mouth and therefore less likely to get lost.”

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) states that an animal cannot officially be classified as extinct until 50 years have passed since its last confirmed sighting in the wild. When Orbell discovered his fabled tracks in the Murchison Mountains of New Zealand’s South Island, it was the spring of 1948. No human had seen a wild Takahe—let alone a living Takahe—since 1898. So following that definition, Orbell was just barely a cryptozoologist.

Yet when Orbell first heard about the Takahe in 1919—after seeing its image printed on a poster insert in the Otago Witness—the world had already written it off as extinct, joining the ranks of the moa and the mammoth. When other children saw the same poster, they probably stared for a moment, and maybe had a fleeting daydream about what it would be like to see a real live Takahe.

The dream was anything but fleeting for 11-year-old Orbell. The idea of finding a Takahe would drive him on a supposed ghost chase for the next 30 years, culminating in a discovery that shocked the world and made Orbell a hero to cryptozoologists everywhere.

The story of the Takahe does not begin with a boy and a poster, however. It begins in the Miocene epoch, between five and twenty million years before Geoffrey Orbell was born. At some point for some reason during this era, a certain species of bird migrated from Australia to New Zealand. Traversing the expanse of water separating the two oceanic islands would have proved impossible for a modern-day Takahe, because it is virtually wingless and hence flightless. But like most organisms that have endured for several million years, the Takahe evolved in numerous ways from its earliest forms.

The ancient airborne ancestor probably bore more of a resemblance to the “Pukeko” or Purple Swamphen, the Takahe’s closest living relative. Like its cousin, the Pukeko made an identical migration to New Zealand, but only within the past millennium.

Observing the two species side-by-side, it is difficult to deny Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. At first glance, the Pukeko and Takahe appear similar: deep blue-purple plumage covering the face, chest, and underbelly; a scarlet red beak, the top half extending upward to the bird’s crown. However, after the Takahe’s ancestor migrated, the species adapted to fit its unthreatening environment.

New Zealand has always been a breeding ground for the strangest and most intriguing birds: the Kakapo, the world’s largest parrot, nocturnal and flightless; the moa, a wingless, flightless giant that stood 12 feet tall; and the Haast’s Eagle, the moa’s only known enemy. For millions of years, New Zealand provided a haven for all avian species—a group of islands free of natural predators until the 13th century.

For this reason, the Takahe lost what the Pukeko retained in Australia: wings, long legs, and an agile body—attributes essential for fleeing from hungry hunters. Over hundreds of thousands of years, the Takahe’s wings reduced significantly in size, rendering the bird essentially flightless. Long red legs ending in widespread claws became stocky. A lean and upright body became chubby and hunched over due to the Takahe’s exclusive concern with bending down to devour snow tussock grass roots, with no need to look out for danger.

Eating has always been the Takahe’s greatest focus and love. Generation after generation has passed down the nutrient-rich daily tradition of waking up, eating, eating, and eating some more, and finally resting in the bushes for the night. A methodical bird, the Takahe uses its claws to dig up grass stalks to feast on the soft, juicy bottoms filled with sugar and protein. When the Takahe’s three favorite flavors of snow tussock grass—broad-leafed, midribbed, and curled—are snowed under during winter, the bird resorts to ferns and herbs.

All that eating makes for one big bird. Weighing in at three kilograms (6.61 pounds) and standing as high as 63 centimeters (24.8 inches), the Takahe is the largest member of the Rallidae family, which includes numerous species of rails, crakes, and the Pukeko. What the bird boasts in size it certainly loses in gracefulness. With each disjointed step, the Takahe lifts its leg slowly, then carefully pads its feet back to the ground. Courting rituals are no prettier. To attract mates, the males employ their awkward excuses for wings.

Once a female falls for this seduction, Takahe love lasts a lifetime. As the winter snow melts in the New Zealand mountains with the coming of spring in October, the pair begins breeding. The female lays an average of two buff eggs soon after, alternating incubation duties with her mate. Takahe chicks are born with brown plumage and no capacity to do anything on their own. Imitating their parents’ lead, however, the kids can be independent soon after three months of care.

For millennia, the Takahe’s clowp call sounded uninterruptedly across alpine grasslands all over North and South Islands. Then, sometime in the late 13th century, the bird’s first threat to survival arrived in westbound canoes.

Hailing from the Polynesian islands, the Maori population feasted on New Zealand’s menu of unafraid prey. Within two centuries, the Maori had hunted all of the moas to extinction, which in turn led to the demise of the Haast’s Eagle. Countless other birds followed, unable to adapt to a world where they were not at the top of the food chain. Many species, including the Takahe, only survived as isolated colonies in remote regions with nearly impenetrable terrain.

By the time famed British explorer Captain James Cook first arrived at the shores of New Zealand in 1769, the Takahe was probably already a critically endangered species—although no one realized it at the time. On North Island, the Takahe (classified as a separate species from its South Island cousin, under the scientific name Porphyrio mantelli) was on the verge of extinction, if not already gone forever. On South Island, Porphyrio hochstetteri survived in small numbers. Between Cook’s arrival and the end of the 19th century, only four official Takahe sightings were recorded, none of them ending particularly well for the bird.

The initial discovery of the species by westerners in 1849 was made by a group of sealers on Resolution Island, when their dogs chased a Takahe into a ravine and dragged the screaming creature back to their masters. Gideon Mantell later recounted this first encounter to the Zoological Society in London:

“Perceiving the trail of a large and unknown bird on the snow with which the ground was covered, they followed the footprint till they obtained a sight of the Takahe, which their dogs instantly pursued, and after a long chase caught alive in the gully of a sound behind Resolution Island. It ran with great speed, and upon being captured uttered loud screams, and fought and struggled violently.”

The bird lived onboard the hunters’ schooner for several days before its meat was consumed and its skin sent to the British Museum.

After a second sighting (and prompt killing) in 1851, only two more Takahe were found before the end of the century. A rabbiter’s dog snatched a specimen in 1879 (nine miles south of Lake Te Anau, where Orbell found them more than half a century later) that was slaughtered soon after; the skeleton was sent to a museum.

The last sighting (before Orbell’s rediscovery a half-century later) came on August 7, 1898, when Donald and Jack Ross watched their dog leap into a bush and emerge clutching a blue-green bird in its teeth. This specimen was mounted by a taxidermist and placed on display at the Otago Museum in Dunedin. As far as the locals were concerned, it was the last Takahe in all of New Zealand.

By 1929, a decade after first learning about the Takahe, Geoffrey Orbell had graduated from Otago Medical School and was working in Invercargill as a specialist practitioner. To the chagrin of Orbell, and undoubtedly many others, cryptozoology does not pay the bills. So although medicine became his career, searching for the Takahe remained a lifelong hobby.

Orbell’s methods were anything but madness. He collected anecdotes and information from a wide variety of people, ranging from park rangers during deer-hunting excursions to patients in his office. He listened to stories of strange tracks and unknown calls and claims of large blue birds people had seen. He took copious notes and carefully analyzed his data. By 1945, he finished building a holiday getaway in Te Anau, not far from the Murchison Mountains and their surrounding valleys.

Aside from being a wholly uncharted region, the Murchisons seemed the most likely haven for any surviving Takahes making a last stand. For two years, Orbell and his friends explored the steep slopes and valleys bordering the shores of Lake Te Anau. And for two years, the search turned up nothing.

Left with only two anecdotal leads—no more substantial than sightings of the Loch Ness monster or Bigfoot—Orbell pondered his next step. In Morris and Smith’sWild South, Orbell recalled his thought process: “Studying the map and thinking about the stories, I began to realize they were all similar in one respect; all the birds were seen or caught on beaches below the bushline.”

In early April 1948, Orbell and his team ascended the terrain toward the western portion of Lake Te Anau. It was here that Orbell measured his first Takahe tracks, although he did not spot a bird during that excursion. Returning home empty-handed but rejuvenated, the doctor began plotting his next move.

In mid-November, however, a local newspaper printed rumors of another search party that would be heading toward the Murchisons by Christmastime. Not to be beaten, Orbell hastily reassembled his team for a trip that very weekend. The search did not last long.

“On November 20 we once more made the arduous climb back to the valley,” said Orbell. “We returned to where we had found the tracks on our last trip. Suddenly, quite near this spot, a large blue-green bird stepped out from amongst the snow tussock. And there . . . stood a living [Takahe], the bird that was ‘supposed’ to be extinct.”

Children, true to their naiveté, dream up the most fantastic ideas and adventures. And those dreams, true to their nature, are not supposed to come to physical fruition, but only exist in the imagination. Yet somehow, on that fateful spring day, with pipe in mouth and camera in hand, Orbell’s childhood dream came to life.

In that instant, the world did not grow any smaller. It just became less mysterious. It makes you wonder: How many more nooks and crannies of our planet remain unexplored or undetected? What else will we uncover with each new stone overturned?

Many people would feel overwhelmed by such grand questions. They are comfortable in their personal domain of familiarity. They might marvel at the unknown, but they will never go further than simply dreaming about a wonderful, mind-boggling expedition. But Geoffrey Orbell’s lifelong obsession—in the face of scientists and doubters—brought about the rediscovery of the Takahe, an animal that was “supposed” to be extinct.

Returning with almost two reels of color film footage, Orbell became an instant international hero. The story made headlines in newspapers from Wellington to London; it even attracted the attention of Time magazine, which described the rediscoverers as returning home in a “state of ornithological ecstasy.”

Despite only finding 250 Takahes along the shores of Lake Te Anau, conservationists took no proactive action to restore the species to a healthy population size. Panic only set in at the onset of the 1970s, when wildlife services noticed that number had dropped by half. This time, however, humans were not directly to blame. The primary animal responsible for the Takahe’s decline was the deer, an introduced species in New Zealand, which competed with the Takahes for tussock grass. As a conservation measure, the government not only allowed but encouraged heavy helicopter hunting to control the deer population.

This strategy, coupled with relocation and captive-breeding programs initiated during the following two decades, has finally restored the Takahe population to its numbers at the time of Orbell’s rediscovery 60 years ago.

The Takahe will now survive and endure in the realm of human consciousness. And as it does, cryptozoologists will continue to search for the Javan tiger and the thylacine and the Bush Moa. We should hope that somebody will achieve another miraculous rediscovery—not simply to confirm a species’ survival, but so that we can celebrate and foster its continued existence.

Eric Karlan is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This is his first article for this magazine.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you