The Snake that Ate Guam’s Birds

By Hugh Powell January 15, 2009

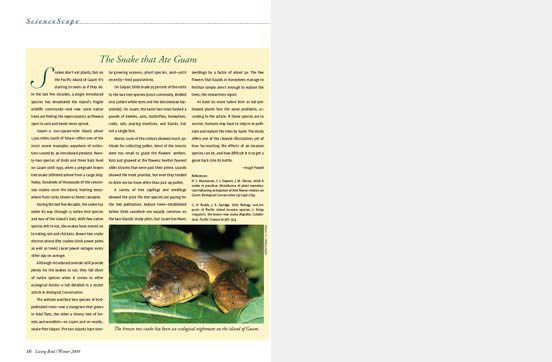

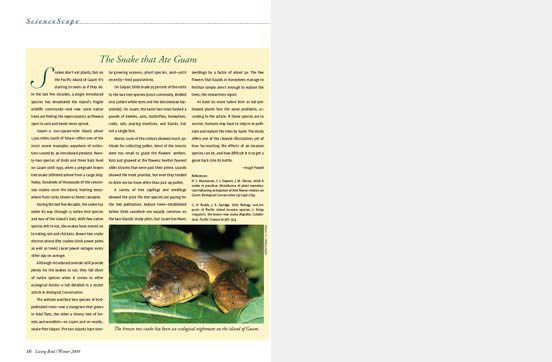

Snakes don’t eat plants, but on the Pacific island of Guam it’s starting to seem as if they do. In the last five decades, a single introduced species has devastated the island’s fragile wildlife community—and now some native trees are feeling the repercussions as flowers open in vain and seeds never sprout.

Guam—a 200-square-mile island about 1,500 miles south of Tokyo—offers one of the most severe examples anywhere of extinction caused by an introduced predator. Twenty-two species of birds and three bats lived on Guam until 1949, when a pregnant brown tree snake slithered ashore from a cargo ship. Today, hundreds of thousands of the venomous snakes cover the island, hunting everywhere from rocky shores to forest canopies.

During the last five decades, the snake has eaten its way through 13 native bird species and two of the island’s bats. With few native species left to eat, the snakes have moved on to eating rats and chickens. Brown tree snake electrocutions (the snakes climb power poles as well as trees) cause power outages every other day on average.

Although introduced animals still provide plenty for the snakes to eat, they fall short of native species when it comes to other ecological duties—a toll detailed in a recent article in Biological Conservation.

The authors watched two species of bird-pollinated trees—one a mangrove that grows in tidal flats, the other a thorny tree of forests and woodlots—on Guam and on nearby, snake-free Saipan. The two islands have similar growing seasons, plant species, and—until recently—bird populations.

On Saipan, birds made 95 percent of the visits to the two tree species (most commonly, Bridled and Golden white-eyes and the Micronesian Myzomela). On Guam, the same two trees hosted a parade of beetles, ants, butterflies, honeybees, crabs, rats, praying mantises, and lizards, but not a single bird.

Worse, none of the visitors showed much aptitude for collecting pollen. Most of the insects were too small to graze the flowers’ anthers. Rats just gnawed at the flowers; beetles favored older blooms that were past their prime. Lizards showed the most promise, but even they tended to drink nectar more often than pick up pollen.

A survey of tree saplings and seedlings showed the price the tree species are paying for the lost pollinators. Mature trees—established before birds vanished—are equally common on the two islands’ study plots, but Guam has fewer seedlings by a factor of about 50. The few flowers that lizards or honeybees manage to fertilize simply aren’t enough to replace the trees, the researchers report.

At least six more native bird- or bat-pollinated plants face the same problems, according to the article. If these species are to survive, humans may have to step in to pollinate and replant the trees by hand. The study offers one of the clearest illustrations yet of how far-reaching the effects of an invasive species can be, and how difficult it is to get a genie back into its bottle.

References:

H. S. Mortensen, Y. L. Dupont, J. M. Olesen. 2008. A snake in paradise: disturbance of plant reproduction following extirpation of bird flower-visitors on Guam. Biological Conservation 141:2146–2154.

G. H. Rodda, J. A. Savidge. 2007. Biology and impacts of Pacific island invasive species. 2. Boiga irregularis, the brown tree snake (Reptilia: Colubridae). Pacific Science 61:307–324.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you