View From Sapsucker Woods: A Fall-Migrant Golden Eagle

by John Fitzpatrick

January 15, 2010

A rare workday visit home for lunch this fall yielded a lucky double encounter with a phenomenon visible in eastern North America only a few days a year. Besides having simple, peaceful beauty in its own right, the experience reminded me how small the earth is, and how powerfully a migrating bird can connect us with real places thousands of miles away.

Just before noon on the second day of November I had begun to enjoy a hurriedly fixed sandwich on our north-facing deck, under a cloudless, crystalline blue sky. High over the distant ridge of hills I noticed a dark speck against the blue. Through binoculars I could see that it was a large raptor on fixed wings, lazily circling on thermals and drifting my way.

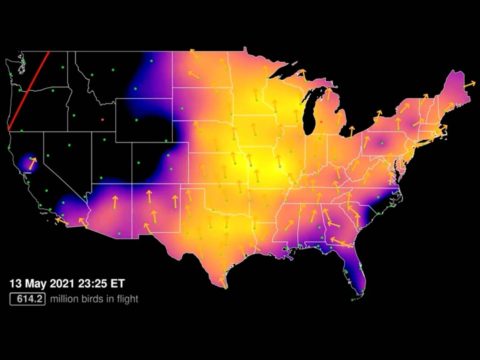

I love these fall days, when hawks of various sorts ride aloft amid pleasant northerly breezes, and make their way south over our heads. If watching for them is like hunting Easter eggs, then identifying them is like opening holiday presents. In this case, the present was extra special. As the raptor got closer, its huge size and long dark wings became apparent and my heart sped up. I hadn’t spotted one of these from my house in several years, so when it got close enough to reveal a white base of the tail and a gleaming golden collar during one of its shallow circles, I literally shouted with joy, “Golden Eagle! Coming right overhead!” My wife and her business partner scurried to join me, and we all quietly took in the spectacle as this big beauty continued its graceful north-to-south aerial tour of Upstate New York, eventually disappearing over the hills to our south. About five minutes later, an almost identical event occurred as a second eagle—this one a full adult, with an all-dark tail—made its silent, circling way southward over the house on the same trajectory as the first.

“Since man came up from barbarism the stately Golden Eagle has been considered the noblest of birds. He it is that typifies royalty among the feathered tribes, and has caused the eagle to be named the king of birds. . . . Comparing him with our national bird, the Bald Eagle, we find that he seems to be built of finer clay” (Edward H. Forbush. 1927. Birds of Massachusetts and Other New England States, Part II, p. 146).

In North America, we tend to picture Golden Eagles against grand western vistas, majestic peaks, high plains, and sagebrush deserts from Alaska to Mexico. In addition, however, a tiny population breeds east of Hudson Bay, mainly on cliffs along the north coast of Quebec and Labrador, and the Gaspé Peninsula.

These eagles migrate south in late October and November to winter as lone individuals along rivers and beaches from the Appalachians to the Gulf Coast. Ithaca, New York, lies under the annual migratory path of a few, and Hawk Mountain, in eastern Pennsylvania, logged 70 Golden Eagles this fall (a record 136 passed by in 2008). Numbers this low make every sighting of this magnificent bird meaningful when we’re lucky enough to spot one in the East. Knowing where a bird comes from as we watch it migrate helps us appreciate each of these creatures as an individual life, as a solitary world traveler on a unique journey across a tiny planet.

In reverie as two eagles soared southward over my head, neither one ever flapping its wings, I drifted north to shiver atop the lonely, wintry, storm-ravaged crags each had left behind just a few days before. Then, back home and warmed again by the midday sun and balmy breezes of Ithaca, I pictured these two drifters making their way back north over frozen landscapes just a few short months from now, in early March. Would they look down and see me marveling at them again? Could I be so lucky?

John Fitzpatrick

Louis Agassiz Fuertes Director

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you