How to record birds for fun and science

By Laura Erickson

April 15, 2010

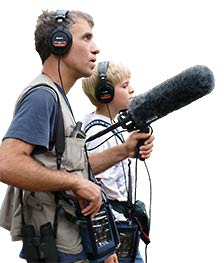

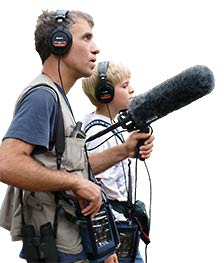

Making your own bird recordings can give you lasting mementos of wonderful birding experiences while providing valuable resources for scientists. And in the same way that binoculars and spotting scopes expand the reach of eyes, sound recording equipment expands the reach of ears, amplifying and homing in on hidden birds and distant sounds. Field trip leaders who hear a distant bird can hand over the headphones to participants and watch their faces light up as they pick up the sound loud and clear.

Macaulay Library Resources

You can teach yourself how to record bird sounds using the wealth of resources at the Macaulay Library website. For a hands-on experience under expert tutelage, the Macaulay Library also offers a week-long Sound Recording Workshop every summer where you can learn what noisy clothing to avoid; how to silently rotate your body to follow a moving sound without moving your feet; how to load your recordings onto a computer, edit them, and make them into CDs; and much more. If you want to borrow recording equipment to field-test it before buying your own, the workshop provides that opportunity as well. Learn more by visiting www.macaulaylibrary.org.

Recording Equipment

You can record birds with a simple digital camera that has a video function, but the tiny microphones pick up much more noise than targeted sounds. The microphone in cell phones is most useful and sensitive for sounds produced within inches of the device. High quality sound equipment is as expensive as high quality optics, and can provide as much satisfaction.

Recorders

Whether you’re using sound equipment to make permanent recordings or simply want to extend your ability to hear distant birds, you’ll need a recorder to plug your microphone and headphones into. There are many kinds of recorders, including cassette and digital tape recorders, minidisks, mp3 players, some iPods, and solid state recorders. Some equipment becomes obsolete very quickly, so it’s a good idea before investing to ask for advice from other recordists. If you’re planning to offer your recordings for scientific use or want the highest quality for your own playback, it’s best to record on tape or save as uncompressed digital files (wav files). After saving the original file for archiving, you can edit and save digital sounds as mp3 files.

Headphones

Headphones connected to recording equipment help you hear exactly what sounds the microphone is picking up. People can’t help but filter out a great many ambient sounds, making birders miss a lot of animal sounds as well. Headphones emphasize every sound, making them much harder to filter out.

Microphone Overview

Studio microphones designed to pick up nearby voices don’t work well outdoors. Two types of microphones are directional enough for recording natural sounds at a distance: the shotgun microphone and the parabolic reflector microphone. Macaulay Library curator Greg Budney says the choice between them depends on what you’re trying to record. Parabolic microphones selectively amplify sound waves entering directly into the parabola and reflected into the microphone, while a shotgun microphone records all the sounds in the general direction it’s pointed without amplifying them.

Parabolic Microphone

The parabolic microphone is a perfect tool for pulling one songbird voice out of the background sounds or from great distances, such as when the bird is in the canopy 200 feet above. A parabola can be ideal for recording wood warblers and other canopy species. When the parabola is properly pointed, the clarity of a single bird’s voice can be breathtaking, but it takes practice to get the sound accurately focused. Whenever the bird moves even slightly, the position of the parabola must follow it exactly.

If you’re trying to record low frequency sounds of owls, grouse, etc., the parabola needs to be quite large or the long wavelength will pass around the parabola rather than being reflected by it into the microphone. Greg Budney explains, “The diameter of a parabola determines the low frequency range of that microphone. Sounds have a physical wavelength, and low sounds have a long wave. If you’re using a 24-inch parabola, you’re not going to be able to capture a Great Horned Owl’s voice or a Ruffed Grouse’s drum. Those sounds wrap right around the parabola like it wasn’t even there. The Ruffed Grouse’s drum can propagate over great distances through forested habitat because the average tree isn’t an impediment for low frequency wavelengths.”

Shotgun Microphone

Shotgun microphones won’t boost the volume of sounds, but they can selectively capture the sounds of a singing bird along with other sounds coming from the same direction. The longer a shotgun microphone is, the narrower, and more precise, its directional properties will be. Shotgun mikes are more portable than parabolas, but may make capturing a single voice above all others more difficult. On the other hand, voices that reverberate will be picked up much better through a shotgun microphone. Greg Budney says, “Anyone who’s tried to track down a Wood Thrush by voice quickly realizes that there are reverberations taking place—elements in that song bounce off the foliage, creating some ventriloquistic effects. When I hear a Wood Thrush, I appreciate hearing that ethereal quality that seems to come from everywhere. A parabola is extremely directional. It actually rejects what we call off-axis sounds—sounds bouncing off vegetation—so you lose that reverberant quality when you use a parabola to record thrushes.”

For more information about sound recording equipment, visit the Macaulay Library’s online review at http://macaulaylibrary.org/documents/AudioEquipment.pdf.

Originally published in the Spring 2010 issue of BirdScope.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you