Crossley’s Influences: Mt. Everest to Michael Jackson

By Hugh Powell March 1, 2011

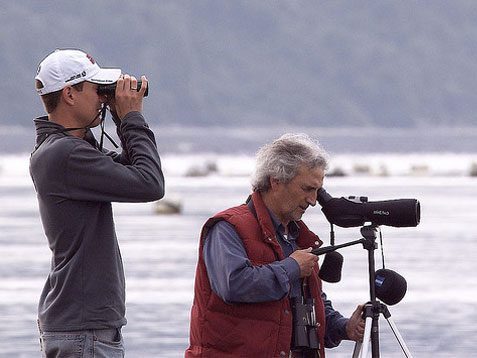

In a talk last night that began with a song and ended with a poem, Richard Crossley described how the innovative format in his new identification guide coalesced from pieces of a lifetime spent birding.

Crossley’s new guide has been called revolutionary and overwhelming (its pros and cons have been reviewed extensively). Each page bombards the reader with multiple poses, plumages, and sizes of a single species, all digitally blended into a photo of typical habitat.

I had been concerned the resulting plates would suffer from image overload. But in his talk Crossley tackled that criticism head on, suggesting that standard field guides might begin to look sterile and lack context by comparison.

He even sees the book’s bulk (more than 3 pounds, far too large for a pocket) as a benefit, because it will encourage birders to pay more attention to the birds themselves. “If I find out people are taking this into the field,” he said, “I’m making the next one heavier.” By the end of his talk his mixture of wisdom and exuberance had won me over.

“The past is what shapes us,” Crossley said as he described his boyhood in Yorkshire, learning egg-collecting from his father and absorbing his definition of art: “a pleasing arrangement of shapes and colors.”

A grammar-school teacher took the young Crossley to see Great Crested Grebes in the local gravel pits, and by 15 he was skipping school to “twitch” rare birds—braving the wrath of the school headmistress in exchange for the second European record of Hudsonian Godwit.

In the Himalaya, Crossley said, he saw a flock of dazzlingly blue Impeyan Pheasants against a backdrop of 6 of the world’s 10 highest peaks. Later, teaching English in Japan, he bought a field guide he couldn’t read. He loved the photos. They showed birds at all angles and in their natural habitat, instead of cut out and arranged at a single size against a white page.

Around that time he went to a Michael Jackson concert and saw the King of Pop moonwalk behind an immense shadow screen. The next time he went out bird watching, he paid attention to silhouettes.

A visit to North America led him to Cape May, where he saw 28 species of warblers in a beach parking lot. He bought some land, built a house (complete with a hawkwatching platform), and moved in. Now in his late 40s and with two kids of his own, his interest has turned to fanning the flames of bird watching in the next generation.

The Crossley ID Guide pulls on many of these threads. The in-your-face assortment of poses and sizes builds on the look of that Japanese field guide and tries to recreate the sense of being out in the field. Crossley champions an approach to identification that values close observation but doesn’t reduce birds to a collection of field marks (similar to our Building Skills tutorials and Inside Birding videos).

He looks at size and shape before he looks at color. In a mixed flock of shorebirds he sees his father’s “pleasing assortments of shapes and colors” and from those patterns draws identifications. He believes that field guides should be studied at home (and left there), so time in the field can be spent actually looking at birds.

He’s convinced that birds are waiting to be discovered anywhere we take the time to look, whether in Cape May or in the middle of nowhere—perhaps especially in the middle of nowhere. And he believes that the only obstacle to having a new generation of young, inspired bird watchers in our country is finding the people willing to teach them.

Apparently, all Crossley wants to do is to reshape bird identification, save American birding, and secure the future of conservation. The fact that it’s impossible to do that singlehandedly didn’t seem to deter him much. “There are other dreamers out there,” he reminded me.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you