Going Nutty for Acorn Woodpeckers

Text and photographs by Marie Read

July 15, 2011

Ask me to describe my perfect photographic subject and I’d probably say a bird that is colorful and attractive, with interesting behavior and predictable habits so you can find it fairly easily. Which bird has all these features? The Acorn Woodpecker—a creature that I’m just nuts about!

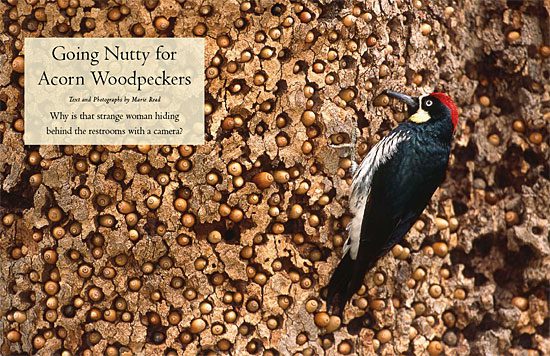

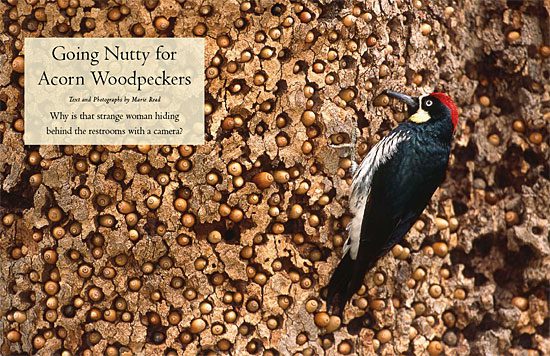

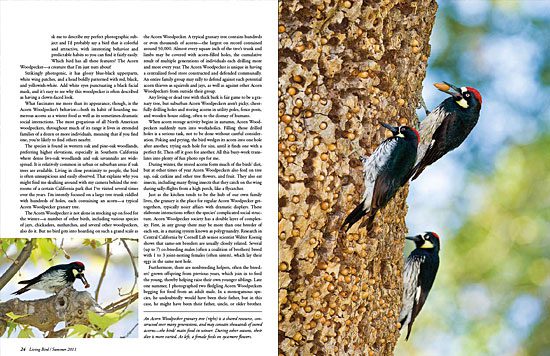

Strikingly photogenic, it has glossy blue-black upperparts, white wing patches, and a head boldly patterned with red, black, and yellowish-white. Add white eyes punctuating a black facial mask, and it’s easy to see why this woodpecker is often described as having a clown-faced look.

What fascinates me more than its appearance, though, is the Acorn Woodpecker’s behavior—both its habit of hoarding numerous acorns as a winter food as well as its sometimes-dramatic social interactions. The most gregarious of all North American woodpeckers, throughout much of its range it lives in extended families of a dozen or more individuals, meaning that if you find one, you’re likely to find others nearby.

The species is found in western oak and pine-oak woodlands, preferring higher elevations, especially in Southern California where dense live-oak woodlands and oak savannahs are widespread. It is relatively common in urban or suburban areas if oak trees are available. Living in close proximity to people, the bird is often unsuspicious and easily observed. That explains why you might find me skulking around with my camera behind the restrooms of a certain California park that I’ve visited several times over the years. I’m intently focused on a large tree trunk riddled with hundreds of holes, each containing an acorn—a typical Acorn Woodpecker granary tree.

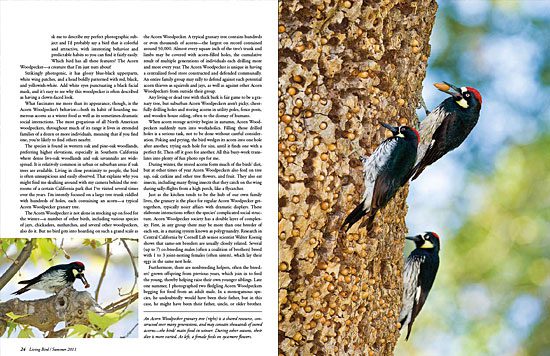

The Acorn Woodpecker is not alone in stocking up on food for the winter—a number of other birds, including various species of jays, chickadees, nuthatches, and several other woodpeckers, also do it. But no bird gets into hoarding on such a grand scale as the Acorn Woodpecker. A typical granary tree contains hundreds or even thousands of acorns—the largest on record contained around 50,000. Almost every square inch of the tree’s trunk and limbs may be covered with acorn-filled holes, the cumulative result of multiple generations of individuals each drilling more and more every year. The Acorn Woodpecker is unique in having a centralized food store constructed and defended communally. An entire family group may rally to defend against such potential acorn thieves as squirrels and jays, as well as against other Acorn Woodpeckers from outside their group.

Any living or dead tree with thick bark is fair game to be a granary tree, but suburban Acorn Woodpeckers aren’t picky, cheerfully drilling holes and storing acorns in utility poles, fence posts, and wooden house siding, often to the dismay of humans.

When acorn storage activity begins in autumn, Acorn Woodpeckers suddenly turn into workaholics. Filling those drilled holes is a serious task, not to be done without careful consideration. Poking and prying, the bird wedges its acorn into one hole after another, trying each hole for size, until it finds one with a perfect fit. Then off it goes for another. All this busy-work translates into plenty of fun photo ops for me.

During winter, the stored acorns form much of the birds’ diet, but at other times of year Acorn Woodpeckers also feed on tree sap, oak catkins and other tree flowers, and fruit. They also eat insects, including many flying insects that they catch on the wing during sally-flights from a high perch, like a flycatcher.

Just as the kitchen tends to be the hub of our own family lives, the granary is the place for regular Acorn Woodpecker get-togethers, typically noisy affairs with dramatic displays. These elaborate interactions reflect the species’ complicated social structure. Acorn Woodpecker society has a double layer of complexity. First, in any group there may be more than one breeder of each sex, in a mating system known as polygynandry. Research in Central California by Cornell Lab senior scientist Walter Koenig shows that same-sex breeders are usually closely related. Several (up to 7) co-breeding males (often a coalition of brothers) breed with 1 to 3 joint-nesting females (often sisters), which lay their eggs in the same nest hole.

Furthermore, there are nonbreeding helpers, often the breeders’ grown offspring from previous years, which join in to feed the young, thereby helping raise their own younger siblings. Late one summer, I photographed two fledgling Acorn Woodpeckers begging for food from an adult male. In a monogamous species, he undoubtedly would have been their father, but in this case, he might have been their father, uncle, or older brother. Furthermore, each youngster might have been related to him differently.

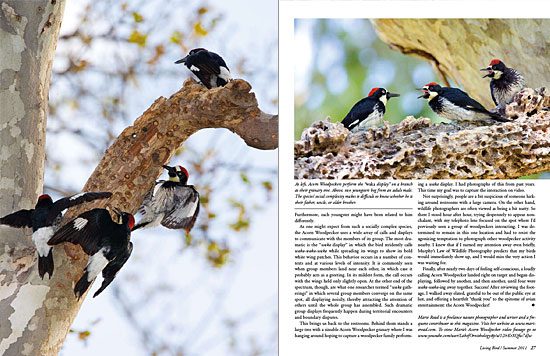

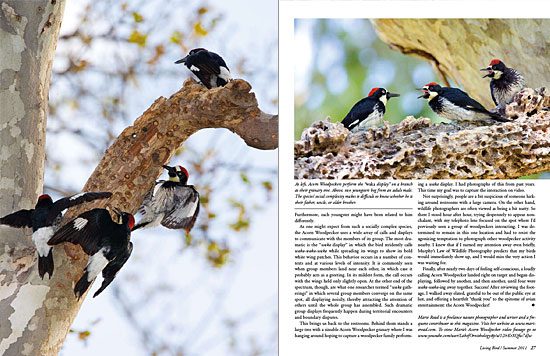

As one might expect from such a socially complex species, the Acorn Woodpecker uses a wide array of calls and displays to communicate with the members of its group. The most dramatic is the “waka display” in which the bird stridently calls waka-waka-waka while spreading its wings to show its bold white wing patches. This behavior occurs in a number of contexts and at various levels of intensity. It is commonly seen when group members land near each other, in which case it probably acts as a greeting. In its mildest form, the call occurs with the wings held only slightly open. At the other end of the spectrum, though, are what one researcher termed “waka gatherings” in which several group members converge on the same spot, all displaying noisily, thereby attracting the attention of others until the whole group has assembled. Such dramatic group displays frequently happen during territorial encounters and boundary disputes.

This brings us back to the restrooms. Behind them stands a large tree with a sizeable Acorn Woodpecker granary where I was hanging around hoping to capture a woodpecker family performing a waka display. I had photographs of this from past years. This time my goal was to capture the interaction on video.

Not surprisingly, people are a bit suspicious of someone lurking around restrooms with a large camera. On the other hand, wildlife photographers are often viewed as being a bit nutty. So there I stood hour after hour, trying desperately to appear nonchalant, with my telephoto lens focused on the spot where I’d previously seen a group of woodpeckers interacting. I was determined to remain in this one location and had to resist the agonizing temptation to photograph other woodpecker activity nearby. I knew that if I turned my attention away even briefly, Murphy’s Law of Wildlife Photography predicts that my birds would immediately show up, and I would miss the very action I was waiting for.

Finally, after nearly two days of feeling self-conscious, a loudly calling Acorn Woodpecker landed right on target and began displaying, followed by another, and then another, until four were waka-waka-ing away together. Success! After reviewing the footage, I walked away elated, grateful to be out of the public eye at last, and offering a heartfelt “thank you” to the epitome of avian entertainment: the Acorn Woodpecker!

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you