Ecuador’s Enchanted Galapagos Islands

Text and photographs by Gary Kramer

July 15, 2011

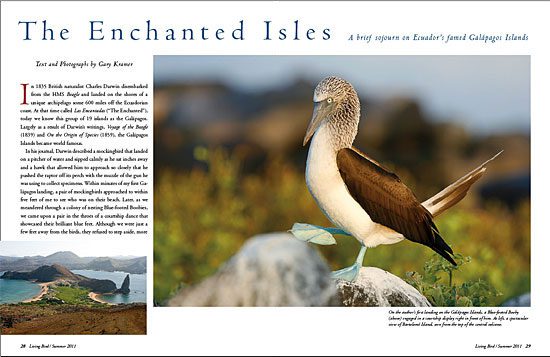

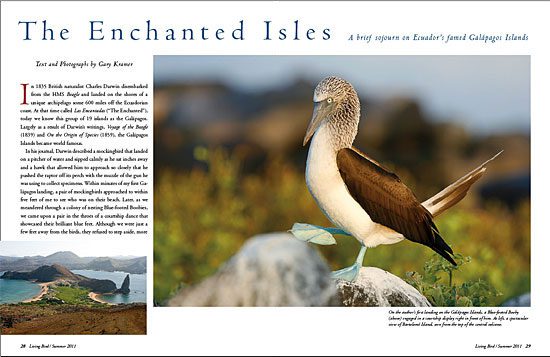

In 1835 British naturalist Charles Darwin disembarked from the HMS Beagle and landed on the shores of a unique archipelago some 600 miles off the Ecuadorian coast. At that time called Las Encantadas (“The Enchanted”), today we know this group of 19 islands as the Galápagos. Largely as a result of Darwin’s writings, Voyage of the Beagle (1839) and On the Origin of Species (1859), the Galápagos Islands became world famous.

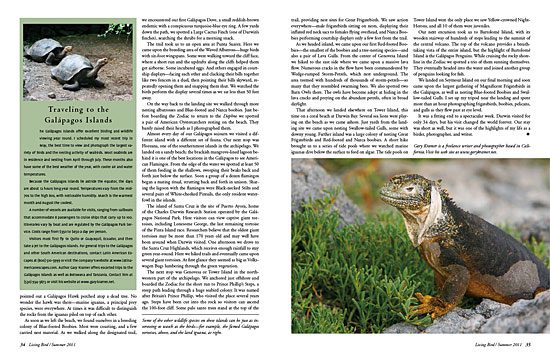

In his journal, Darwin described a mockingbird that landed on a pitcher of water and sipped calmly as he sat inches away and a hawk that allowed him to approach so closely that he pushed the raptor off its perch with the muzzle of the gun he was using to collect specimens. Within minutes of my first Galápagos landing, a pair of mockingbirds approached to within five feet of me to see who was on their beach. Later, as we meandered through a colony of nesting Blue-footed Boobies, we came upon a pair in the throes of a courtship dance that showcased their brilliant blue feet. Although we were just a few feet away from the birds, they refused to step aside, more intent on each other than on the tourists invading their domain. Now, more than 175 years after Darwin first set foot on these shores, the birds and other wildlife seem as unconcerned about humans as they were in his day.

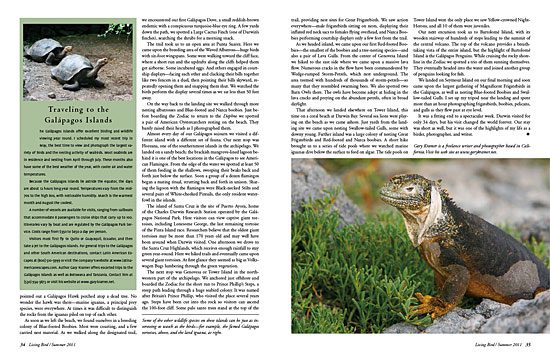

To travel to the Galápagos is to experience one of the world’s great wildlife spectacles. Although some of the bird species—such as frigatebirds, boobies, flamingos, and Great Blue Herons—are common elsewhere, nowhere else are they so relaxed and approachable. Visitors can watch male Great Frigatebirds displaying with their inflated red neck pouches as females fly past. Visitors can swim with Galápagos Penguins in the shallows as they chase small fish or watch a Galápagos Mockingbird pick parasites and dead skin from the back of a marine iguana, often from only a few feet away.

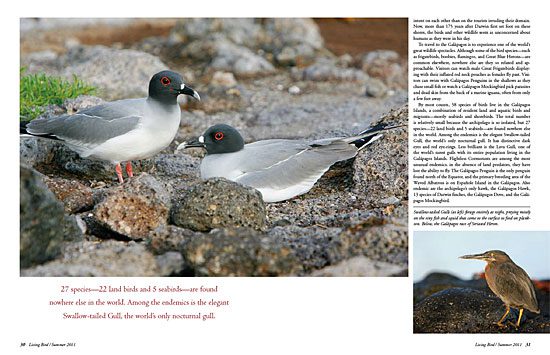

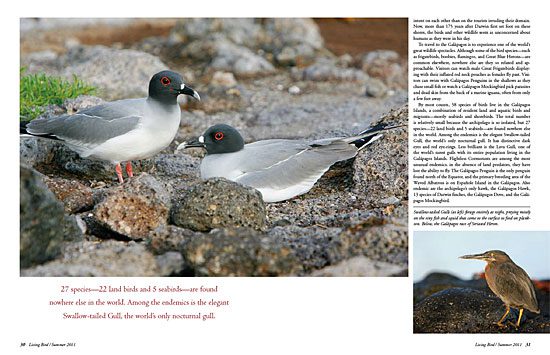

By most counts, 58 species of birds live in the Galápagos Islands, a combination of resident land and aquatic birds and migrants—mostly seabirds and shorebirds. The total number is relatively small because the archipelago is so isolated, but 27 species—22 land birds and 5 seabirds—are found nowhere else in the world. Among the endemics is the elegant Swallow-tailed Gull, the world’s only nocturnal gull. It has distinctive dark eyes and red eye-rings. Less brilliant is the Lava Gull, one of the world’s rarest gulls with its entire population living in the Galápagos Islands. Flightless Cormorants are among the most unusual endemics; in the absence of land predators, they have lost the ability to fly. The Galápagos Penguin is the only penguin found north of the Equator, and the primary breeding area of the Waved Albatross is on Españole Island in the Galápagos. Also endemic are the archipelago’s only hawk, the Galápagos Hawk, 13 species of Darwin finches, the Galápagos Dove, and the Galápagos Mockingbird.

As a travel guide, I had booked a one-week trip to the Galápagos for 16 passengers. National Park rules require that a park-certified guide must accompany visitors, and 16 is the largest group one guide can accompany. Visitors can reach the Galápagos by jet from either Quito or Guayaquil, Ecuador. From Guayaquil, the flight takes about 90 minutes. Most flights land at the Baltra Airport, a landing strip originally built by the United States military during World War II.

When we arrived, our guide Charlie greeted us at the airport, and after gathering our luggage, we boarded a bus for the 15-minute ride to Baltra Harbor. Here a Zodiac inflatable was waiting to ferry us to our mobile base of operations—the Daphne, a 70-foot motor yacht. For the most part, travelers visiting the Galápagos Islands stay on boats, although Puerto Ayora, the principal town, has some accommodations on land.

Our first full day dawned bright and clear, and after breakfast we boarded the Zodiac for the short run to South Plaza Island. Formed by an uplifted lava fault, this small island supports a variety of birds and other wildlife. Several sea lions lounged near the landing site, glancing up at us unconcernedly before resuming their naps. Almost immediately we spotted a Striated Heron, searching for prey along the shoreline. Nearby, a huge land iguana ate a fallen cactus pad.

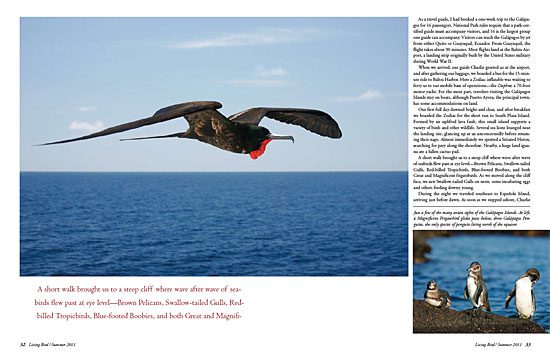

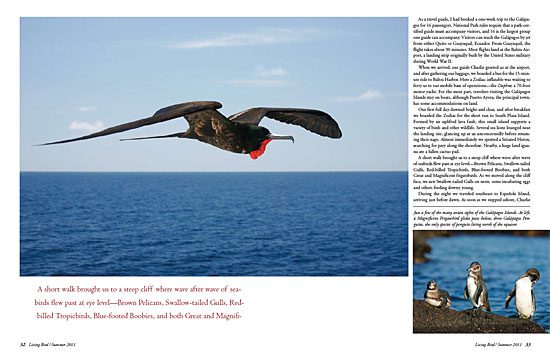

A short walk brought us to a steep cliff where wave after wave of seabirds flew past at eye level—Brown Pelicans, Swallow-tailed Gulls, Red-billed Tropicbirds, Blue-footed Boobies, and both Great and Magnificent frigatebirds. As we moved along the cliff face, we saw Swallow-tailed Gulls on nests, some incubating eggs and others feeding downy young.

During the night we traveled southeast to Españole Island, arriving just before dawn. As soon as we stepped ashore, Charlie pointed out a Galápagos Hawk perched atop a dead tree. No wonder the hawk was there—marine iguanas, a principal prey species, were everywhere. At times it was difficult to distinguish the rocks from the iguanas piled on top of each other.

As soon as we left the beach, we found ourselves in a breeding colony of Blue-footed Boobies. Most were courting, and a few carried nest material. As we walked along the designated trail, we encountered our first Galápagos Dove, a small reddish-brown endemic with a conspicuous turquoise-blue eye ring. A few yards down the path, we spotted a Large Cactus Finch (one of Darwin’s finches), searching the shrubs for a morning snack.

The trail took us to an open area at Punta Suarez. Here we came upon the breeding area of the Waved Albatross—huge birds with six-foot wingspans. Some were walking toward the cliff face, where a short run and the updrafts along the cliffs helped them get airborne. Some incubated eggs. And others engaged in courtship displays—facing each other and clacking their bills together like two fencers in a duel, then pointing their bills skyward, repeatedly opening them and snapping them shut. We watched the birds perform the display several times as we sat less than 50 feet away.

On the way back to the landing site we walked through more nesting albatrosses and Blue-footed and Nazca boobies. Just before boarding the Zodiac to return to the Daphne we spotted a pair of American Oystercatchers resting on the beach. They barely raised their heads as I photographed them.

Almost every day of our Galápagos sojourn we visited a different island with a different set of fauna. Our next stop was Floreana, one of the southernmost islands in the archipelago. We landed on a sandy beach; the brackish mangrove-lined lagoon behind it is one of the best locations in the Galápagos to see American Flamingos. From the edge of the water we spotted at least 50 of them feeding in the shallows, sweeping their beaks back and forth just below the surface. Soon a group of a dozen flamingos began a mating ritual, strutting back and forth in unison. Sharing the lagoon with the flamingos were Black-necked Stilts and several pairs of White-cheeked Pintails, the only resident waterfowl in the islands.

The island of Santa Cruz is the site of Puerto Ayora, home of the Charles Darwin Research Station operated by the Galápagos National Park. Here visitors can view captive giant tortoises, including Lonesome George, the last remaining tortoise of the Pinta Island race. Researchers believe that the oldest giant tortoises may be more than 170 years old and may well have been around when Darwin visited. One afternoon we drove to the Santa Cruz Highlands, which receives enough rainfall to stay green year-round. Here we hiked trails and eventually came upon several giant tortoises. At first glance they seemed as big as Volkswagen Bugs lumbering through the green vegetation.

The next stop was Genovesa or Tower Island in the northwestern part of the archipelago. We anchored just offshore and boarded the Zodiac for the short run to Prince Phillip’s Steps, a steep path leading through a huge seabird colony. It was named after Britain’s Prince Phillip, who visited the place several years ago. Steps have been cut into the rock so visitors can ascend the 100-foot cliff. Some palo santo trees stand at the top of the trail, providing nest sites for Great Frigatebirds. We saw action everywhere—male frigatebirds sitting on nests, displaying their inflated red neck sacs to females flying overhead, and Nazca Boobies performing courtship displays only a few feet from the trail.

As we headed inland, we came upon our first Red-footed Boobies—the smallest of the boobies and a tree-nesting species—and also a pair of Lava Gulls. From the center of Genovesa Island we hiked to the east side where we came upon a massive lava flow. Numerous cracks in the flow have been commandeered by Wedge-rumped Storm-Petrels, which nest underground. The area teemed with hundreds of thousands of storm-petrels—so many that they resembled swarming bees. We also spotted two Barn Owls there. The owls have become adept at hiding in the lava cracks and preying on the abundant petrels, often in broad daylight.

That afternoon we landed elsewhere on Tower Island, this time on a coral beach at Darwin Bay. Several sea lions were playing on the beach as we came ashore. Just yards from the landing site we came upon nesting Swallow-tailed Gulls, some with downy young. Farther inland was a large colony of nesting Great Frigatebirds and Red-footed and Nazca boobies. A short hike brought us to a series of tide pools where we watched marine iguanas dive below the surface to feed on algae. The tide pools on Tower Island were the only place we saw Yellow-crowned Night-Herons, and all 10 of them were juveniles.

Our next excursion took us to Bartolomé Island, with its wooden stairway of hundreds of steps leading to the summit of the central volcano. The top of the volcano provides a breathtaking vista of the entire island, but the highlight of Bartolomé Island is the Galápagos Penguins. While cruising the rocky shoreline in the Zodiac we spotted a trio of them sunning themselves. They eventually headed into the water and joined another group of penguins looking for fish.

We landed on Seymour Island on our final morning and soon came upon the largest gathering of Magnificent Frigatebirds in the Galápagos, as well as nesting Blue-footed Boobies and Swallow-tailed Gulls. I set up my tripod near the landing and spent more than an hour photographing frigatebirds, boobies, pelicans, and gulls as they flew past at eye level.

It was a fitting end to a spectacular week. Darwin visited for only 34 days, but his visit changed the world forever. Our stay was short as well, but it was one of the highlights of my life as a birder, photographer, and writer.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you