Whimbrel Survives Tropical Storm, Shot in Caribbean

September 13, 2011

A migrating Whimbrel named Machi has been shot on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, French West Indies. The bird (pictured at left) had likely landed to rest up after detouring around Tropical Storm Maria. Machi became one of thousands of shorebirds that are hunted for sport each fall—but she stood out from the flock because of a satellite tracking tag applied by scientists at the Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary. The hunter contacted a local wildlife biologist to report what he’d found.

Though Whimbrels (and most other North American birds) are protected in the U.S., Mexico, and Canada by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act it’s legal to hunt them on several Caribbean islands and there are no bag limits, said Lisa Sorenson of Boston University, who is president of the Society for the Conservation and Study of Caribbean Birds. Hunting has a strong tradition in the Caribbean, especially on Guadeloupe and nearby Martinique and Barbados. Guadeloupe has about 3,000 hunters, the most active of whom may take 500 to 1,000 shorebirds in a single season, according to a 2011 report. Precise figures are hard to come by, but frequently shot species likely include Lesser Yellowlegs, Pectoral Sandpiper, Stilt Sandpiper, Short-billed Dowitcher, Greater Yellowlegs, and American Golden-Plover, according to the report. Some Whimbrels visit during fall migration or winter, but many stop in the Caribbean only when forced down by bad weather—Machi had not visited Guadeloupe in previous years.

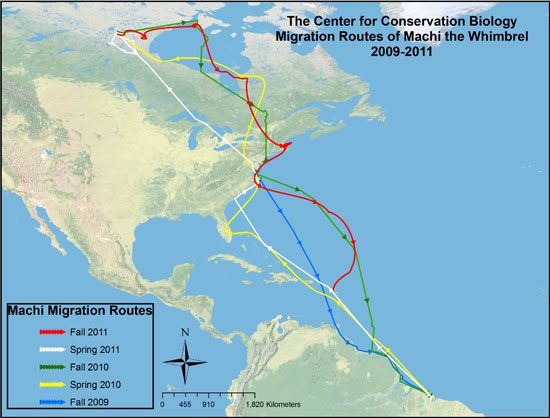

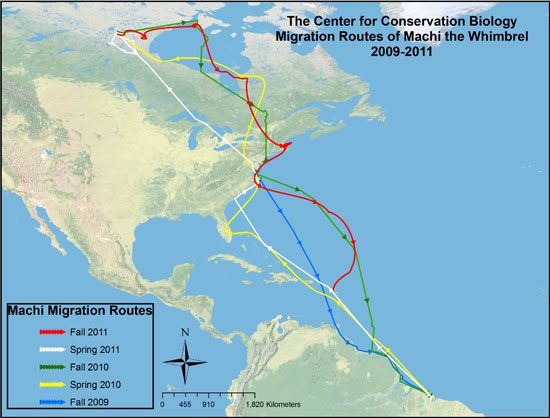

Machi was first caught and tagged in August, 2009, on a Nature Conservancy reserve in Virginia. Fletcher Smith, a biologist at the William and Mary center, applied the tag, and over the next two years Machi drew a detailed map of staggering athletic feats: more than 27,000 miles traveled; seven separate, nonstop flights of more than 2,000 miles; yearly trips between breeding grounds near Hudson Bay and wintering grounds in Sao Luis, Brazil. The red line in the map shows Machi’s last flights from Hudson Bay, including the long arc she made around Maria; the track ends in Guadeloupe (other colors show Machi’s routes in previous seasons).

The Center for Conservation Biology is still tracking four other Whimbrels and have tracked 13 others in previous years; you can see migration maps for them all on their site.

According to Sorenson, when the hunter returned Machi’s transmitter, the Guadeloupe wildlife biologist told him Machi’s history and the distances she had traveled. “He was amazed; he just had no idea what these birds are capable of,” Sorenson said. Though flocks of birds can blur into anonymity, knowing the name and history of a single individual can somehow resharpen the focus. Hunters who live on the islands, and who have hunted all their lives, must see the annual arrival of shorebirds as an abundance that returns undiminished every year. It’s traditional to go out hunting after hurricanes have passed, to shoot what the bad weather has brought in, Smith said.

The solution to the problem, Sorenson hopes, lies in raising awareness of shorebirds’ plight in the larger world—including population declines and habitat loss. “It’s important not to offend the hunters and shut down communications,” she said, “but hunting regulations need to be updated.” In the Bahamas hunting used to be unrestricted, but recent bag limits of 50 birds per day have been put in place, and hunter education, including involving hunters in banding and population counts, have helped raise awareness and develop a conservation ethic.

On Barbados, hunters have voluntarily agreed not to shoot American Golden-Plovers or Red Knots, birds of high conservation concern. “We want to have that approach in Guadeloupe and Martinique,” Sorenson said, “where we work with the hunters to find a solution. [Machi’s death] is a really, really sad event, but the reality is it’s happening to thousands of birds every fall. This is a good opportunity to encourage these governments to adopt more sustainable hunting regulations, such as bag limits, as well as protect some wetlands as refuges.”

(Map courtesy of the Center for Conservation Biology. The Whimbrel tracking project is a collaboration of the Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary, the Nature Conservancy, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program, and Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences.)

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you