Beyond the Empty Nest: Where Do Fledglings Go?

By Hugh Powell; Photograph by Tom Vezo/Vireo

October 15, 2011

As anyone who’s ever sent a son or daughter off to college knows, a safe departure from the nest may warrant a sigh of relief, but the worries aren’t over. Fortunately for humans, by the time our kids leave home they have an extremely good chance of survival.

For birds it’s not nearly so simple: a spate of recent research is beginning to show just how fraught with peril the life of a juvenile bird is. Aided by lightweight technology, researchers are following fledglings as they leave the nest, and finding they don’t always go where one might think.

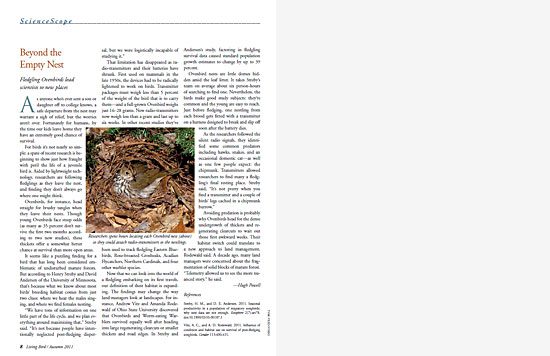

Ovenbirds, for instance, head straight for brushy tangles when they leave their nests. Though young Ovenbirds face steep odds (as many as 35 percent don’t survive the first two months according to two new studies), these thickets offer a somewhat better chance at survival than more open areas.

It seems like a puzzling finding for a bird that has long been considered emblematic of undisturbed mature forests. But according to Henry Streby and David Andersen of the University of Minnesota, that’s because what we know about most birds’ breeding habitat comes from just two clues: where we hear the males singing, and where we find females nesting.

“We have tons of information on one little part of the life cycle, and we plan everything around maximizing that,” Streby said. “It’s not because people have intentionally neglected post-fledging dispersal, but we were logistically incapable of studying it.”

That limitation has disappeared as radio-transmitters and their batteries have shrunk. First used on mammals in the late 1950s, the devices had to be radically lightened to work on birds. Transmitter packages must weigh less than 5 percent of the weight of the bird that is to carry them—and a full-grown Ovenbird weighs just 16–28 grams. New radio-transmitters now weigh less than a gram and last up to six weeks. In other recent studies they’ve been used to track fledgling Eastern Bluebirds, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, Acadian Flycatchers, Northern Cardinals, and four other warbler species.

Now that we can look into the world of a fledgling embarking on its first travels, our definition of their habitat is expanding. The findings may change the way land managers look at landscapes. For instance, Andrew Vitz and Amanda Rodewald of Ohio State University discovered that Ovenbirds and Worm-eating Warblers survived equally well after heading into large regenerating clearcuts or smaller thickets and road edges. In Streby and Andersen’s study, factoring in fledgling survival data caused standard population growth estimates to change by up to 39 percent.

Ovenbird nests are little domes hidden amid the leaf litter. It takes Streby’s team on average about six person-hours of searching to find one. Nevertheless, the birds make good study subjects: they’re common and the young are easy to reach. Just before fledging, one nestling from each brood gets fitted with a transmitter on a harness designed to break and slip off soon after the battery dies.

As the researchers followed the silent radio signals, they identified some common predators including hawks, snakes, and an occasional domestic cat—as well as one few people expect: the chipmunk. Transmitters allowed researchers to find many a fledgling’s final resting place. Streby said, “It’s not pretty when you find a transmitter and a couple of birds’ legs cached in a chipmunk burrow.”

Avoiding predation is probably why Ovenbirds head for the dense undergrowth of thickets and regenerating clearcuts to wait out those first awkward weeks. Their habitat switch could translate to a new approach to land management, Rodewald said. A decade ago, many land managers were concerned about the fragmentation of solid blocks of mature forest. “Telemetry allowed us to see the more nuanced story,” she said.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you