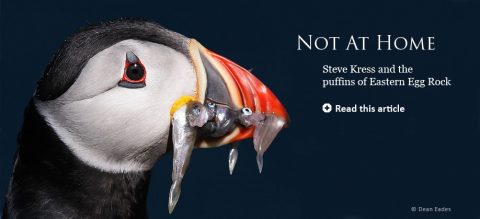

Not At Home: Stephen Kress and the Puffins of Eastern Egg Rock, Maine

By Peter Cashwell; Photographs by Arthur Morris and Bill Scholtz

October 15, 2011

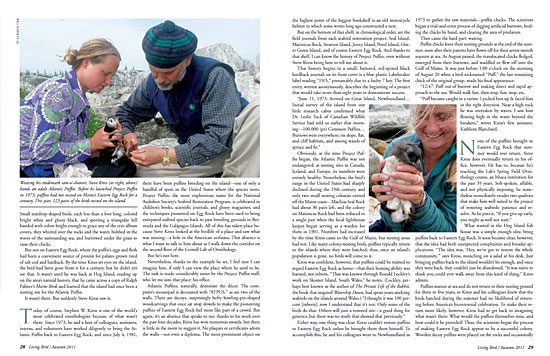

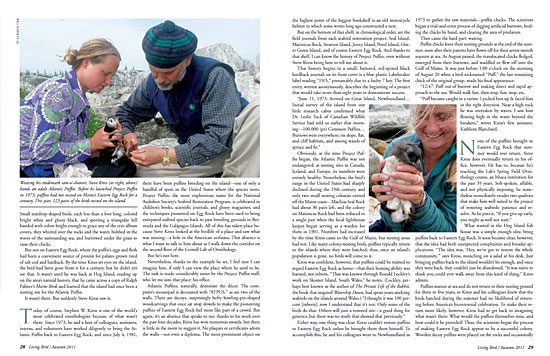

When Steve Kress first visited the place, there was something he didn’t see. It was the summer of 1969, and he had a job at the Audubon Society’s Hog Island Camp. As part of his duties, he traveled to a low, treeless island called Eastern Egg Rock, ringed with rocks and crowned with grass, squatting six miles off the coast of Maine. He could see that it was home to a variety of birds, including Herring Gulls and Great Black-backed Gulls, but because of the host of hungry fishermen and sailors who had once stopped at the island regularly, he couldn’t see the thing they had stopped for.

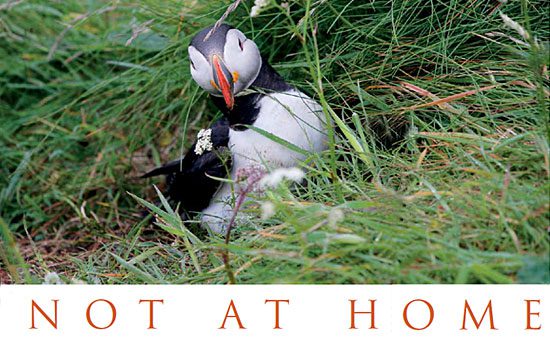

That thing was the Atlantic Puffin, a bird Kress had seen in 1967, on Machias Seal Island, during one of his previous summer jobs at the Sunbury Shores Arts and Nature Centre in New Brunswick, Canada. Small teardrop-shaped birds, each less than a foot long, colored bright white and glossy black, and sporting a triangular bill banded with colors bright enough to grace any of the era’s album covers, they whirred over the rocks and the water, bobbed in the waves of the surrounding sea, and burrowed under the grass to raise their chicks.

But not on Eastern Egg Rock, where the puffin’s eggs and flesh had been a convenient source of protein for palates grown tired of salt cod and hardtack. By the time Kress set eyes on the island, the bird had been gone from it for a century, but he didn’t yet see that. It wasn’t until he was back at Hog Island, reading up on the area’s natural history, that he came across a copy of Ralph Palmer’s Maine Birds and learned that the island had once been a nesting site for the Atlantic Puffin.

It wasn’t there. But suddenly Steve Kress saw it.

Today, of course, Stephen W. Kress is one of the world’s most celebrated ornithologists because of what wasn’t there. Since 1973, he and a host of colleagues, assistants, interns, and volunteers have worked diligently to bring the Atlantic Puffin back to Eastern Egg Rock, and since July 4, 1981, there have been puffins breeding on the island—one of only a handful of spots in the United States where the species nests. Project Puffin, the more euphonious name for the National Audubon Society’s Seabird Restoration Program, is celebrated in children’s books, scientific journals, and glossy magazines, and the techniques pioneered on Egg Rock have been used to bring extirpated seabird species back to past breeding grounds in Bermuda and the Galápagos Islands. All of this has taken place because Steve Kress looked at the birdlife of a place and saw what was missing—a hole in the American avifauna. That absence is what I want to talk to him about as I walk down the corridor on the second floor of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

But he’s not here.

Nevertheless, thanks to the example he set, I feel sure I can imagine him, if only I can view the place where he used to be. The task is made considerably easier by the Project Puffin staff, who let me into that place: his office.

Atlantic Puffins, naturally, dominate the décor. The computer’s mousepad is decorated with “ATPUS,” as are two of the walls. There are decoys, surprisingly hefty bowling-pin-shaped woodcarvings that once sat atop dowels to make the pioneering puffins of Eastern Egg Rock feel more like part of a crowd. But again, it’s an absence that speaks to me: thanks to his work over the past four decades, Kress has won numerous awards, but there is little in the room to suggest it. No plaques or certificates adorn the walls—not even a diploma. The most prominent object on the highest point of the biggest bookshelf is an old motorcycle helmet in which some wrens long ago constructed a nest.

But on the bottom of that shelf, in chronological order, are the field journals from each seabird restoration project: Seal Island, Matinicus Rock, Stratton Island, Jenny Island, Pond Island, Outer Green Island, and of course Eastern Egg Rock. And thanks to that shelf, I can know the history of Project Puffin, even without Steve Kress being here to tell me about it.

That history begins in a small, battered, red-spined black hardback journal; on its front cover is a blue plastic Labelmaker label reading “19/3,” presumably due to a faulty 7 key. The first entry, written anonymously, describes the beginning of a project that would take more than eight years to demonstrate success.

“June 11, 1973: Arrived on Great Island, Newfoundland… Initial survey of the island from our little research cabin confirmed what Dr. Leslie Tuck of Canadian Wildlife Service had told us earlier that morning—100,000 (pr) Common Puffins… Burrows were everywhere, on slope, flat, and cliff habitats, and among stands of spruce and fir.”

Obviously, at the time Project Puffin began, the Atlantic Puffin was not endangered; at nesting sites in Canada, Iceland, and Europe, its numbers were entirely healthy. Nonetheless, the bird’s range in the United States had sharply declined during the 19th century, and only two small nesting colonies existed off the Maine coast—Machias Seal Rock had about 30 pairs left, and the colony on Matinicus Rock had been reduced to a single pair when the local lighthouse keeper began serving as a warden for them in 1901. Numbers had increased by the time Kress came to the Gulf of Maine, but nesting areas had not. Like many colony-nesting birds, puffins typically return to the islands where they were hatched; thus, once an island’s population is gone, no birds will come to it.

Kress was confident, however, that puffins could be trained to regard Eastern Egg Rock as home—that their homing ability was learned, not inborn. “That was known through Ronald Lockley’s work on Skomer Island, South Wales,” he notes. (Lockley, perhaps best known as the author of The Private Life of the Rabbit, the book that inspired Watership Down, had spent years studying seabirds on the islands around Wales.) “I thought it was 100 percent[inborn]; now I understand that it’s not. Only some of the birds do that. Others will join a restored site—a good thing for genetics, but there was no study that showed that previously.”

Either way, one thing was clear: Kress couldn’t restore puffins to Eastern Egg Rock unless he brought them there himself. To accomplish this, he and his colleagues went to Newfoundland in 1973 to gather the raw materials—puffin chicks. The scientists began a trial-and-error process of digging artificial burrows, feeding the chicks by hand, and clearing the area of predators.

Then came the hard part: waiting.

Puffin chicks leave their nesting grounds at the end of the summer, soon after their parents have flown off for their seven-month sojourn at sea. As August passed, the translocated chicks fledged, emerged from their burrows, and waddled or flew off into the Gulf of Maine. It was just before 1:00 o’clock on the morning of August 20 when a bird nicknamed “Puff,” the last remaining chick of the original group, made his final appearance:

“12:47: Puff out of burrow and making direct and rapid approach to the sea. Would walk fast, then stop, fast, stop, etc.

“Puff became caught in a ravine. I picked him up & faced him in the right direction. Near a high rock he was overtaken by waves. I saw him floating high in the water beyond the breakers,” wrote Kress’s first assistant, Kathleen Blanchard.

None of the puffins brought to Eastern Egg Rock that summer would ever return. Steve Kress does eventually return to his office, however. He has to, because he’s teaching the Lab’s Spring Field Ornithology course, an Ithaca institution for the past 35 years. Soft-spoken, affable, and not physically imposing, he nonetheless immediately exudes two qualities that make him well suited to the project of restoring seabirds: patience and resolve. As he puts it, “If you give up early, you might as well not start.”

What started in the Hog Island fish house was a simple enough idea: bring puffins back to Eastern Egg Rock. It soon became clear, however, that the idea had both unexpected complexities and broader applications. “The idea was, ‘Hey, we’ve got to restore the whole community,’” says Kress, munching on a salad at his desk. Just bringing puffins back to the island wouldn’t be enough, and once they were back, they couldn’t just be abandoned. “It was naïve to think you could ever walk away from this kind of thing,” Kress admits.

Puffins mature at sea and do not return to their nesting ground for three to five years, so Kress and his colleagues knew that the birds hatched during the summer had no likelihood of returning before America’s bicentennial celebration. To make their return more likely, however, Kress had to get back to imagining what wasn’t there: What would the puffins themselves miss, and how could it be provided? Thus, the scientists began the process of making Eastern Egg Rock appear to be a successful colony. Wooden decoy puffins were placed on the rocks and occasionally set floating off the shoreline. Mirrors were set up to multiply the motions and appearances of the birds that might come to the island. And of course there was still the problem of what puffins need to be absent: gulls.

Herring and Great Black-backed gulls are notorious predators of eggs and chicks, and during the 100-year absence of puffins on Eastern Egg Rock, the gulls had thrived there, living on fish and fishermen’s garbage. Kress knew that the puffin colony would never survive the gulls so long as it depended on human beings for its defense.

“The whole ecosystem is so badly distorted by human pressure,” Kress points out. “At Western Egg Rock, for example, there is a colony of Great Black-backed and Herring gulls—they’re the steady state; they will eventually nest on former puffin and tern colonies. You can get other species to come back, but keeping them there is very unlikely.”

Luckily, there was a way to kill two birds with this particular stone, so to speak: if the scientists could persuade terns to nest near the puffins, the gulls might be kept at bay. Terns are relentless in defense of their nests—a trait that eventually led Kress to adopt a tam-o’-shanter as his standard headgear, because the birds would attack the tassel on the crown, rather than him—and with many of the same techniques they had used for puffins, a breeding population of terns was established on Egg Rock. “From the puffin’s point of view,” he says, “it’s an umbrella hanging over the colony.”

Still, it was a long wait. A puffin with a Project Puffin band was spotted at sea in 1977, and a few more turned up in the colony on Matinicus Rock, but Eastern Egg Rock remained puffinfree, except for the young birds Kress and his team translocated every May and watched vanish every August. Then a few banded birds began to appear—an encouraging development—but not to breed.

The volunteers maintained their sense of humor nonetheless. Richard Podolsky’s notes in the 1981 journal are filled with cracks about everything from the Spartan living arrangements on the Rock to the peanut butter-tomato-and-onion sandwiches constructed by Shad Northshield, and he dryly asks, when one of his colleagues moves from Eastern Egg Rock to Matinicus, “Will he just visit or stay to breed?”

But on July 4, the tone of the journal’s notes shifts abruptly. One of the team members spotted a puffin with fish in its bill. The fish in question were being carried to the island, rather than being consumed at sea—a development that could only mean one thing: somewhere on the island there was a chick to be fed. Steve Kress wrote that day: “It was the sight we had all done much watching for—but little talking…the best proof we will probably have that after 100 years of absence and nine years of working toward this goal, puffins are again nesting at Eastern Egg Rock—a Fourth of July celebration I’ll never forget.”

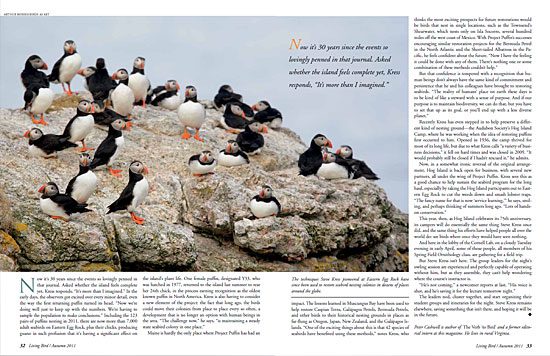

Now it’s 30 years since the events so lovingly penned in that journal. Asked whether the island feels complete yet, Kress responds, “It’s more than I imagined.” In the early days, the observers got excited over every minor detail, even the way the first returning puffin turned its head. “Now we’re doing well just to keep up with the numbers. We’re having to sample the population to make conclusions.” Including the 123 pairs of puffins nesting in 2011, there are now more than 7,000 adult seabirds on Eastern Egg Rock, plus their chicks, producing guano in such profusion that it’s having a significant effect on the island’s plant life. One female puffin, designated Y33, who was hatched in 1977, returned to the island last summer to rear her 24th chick, in the process earning recognition as the oldest known puffin in North America. Kress is also having to consider a new element of the project: the fact that long ago, the birds could move their colonies from place to place every so often, a development that is no longer an option with human beings in the area. “The challenge now,” he says, “is maintaining a steady state seabird colony in one place.”

Maine is hardly the only place where Project Puffin has had an impact. The lessons learned in Muscungus Bay have been used to help restore Caspian Terns, Galápagos Petrels, Bermuda Petrels, and other birds to their historical nesting grounds in places as far-flung as Oregon, Japan, New Zealand, and the Galápagos Islands. “One of the exciting things about this is that 42 species of seabirds have benefited using these methods,” notes Kress, who thinks the most exciting prospects for future restorations would be birds that nest in single locations, such as the Townsend’s Shearwater, which nests only on Isla Socorro, several hundred miles off the west coast of Mexico. With Project Puffin’s successes encouraging similar restoration projects for the Bermuda Petrel in the North Atlantic and the Short-tailed Albatross in the Pacific, he feels confident about the future. “Now I have the feeling it could be done with any of them. There’s nothing one or some combination of these methods couldn’t help.”

But that confidence is tempered with a recognition that human beings don’t always have the same kind of commitment and persistence that he and his colleagues have brought to restoring seabirds. “The reality of humans’ place on earth these days is to be kind of like a steward with a sense of purpose. And if our purpose is to maintain biodiversity, we can do that, but you have to set that up as its goal, or you’ll end up with a less diverse planet.”

Recently Kress has even stepped in to help preserve a different kind of nesting ground—the Audubon Society’s Hog Island Camp, where he was working when the idea of restoring puffins first occurred to him. Opened in 1936, the camp thrived for most of its long life, but due to what Kress calls “a variety of business decisions,” it fell on hard times and was closed in 2009. “It would probably still be closed if I hadn’t rescued it,” he admits.

Now, in a somewhat ironic reversal of the original arrangement, Hog Island is back open for business, with several new partners, all under the wing of Project Puffin. Kress sees this as a good chance to help sustain the seabird program for the long haul, especially by taking the Hog Island participants out to Eastern Egg Rock to cut the weeds down and smash lobster traps. “The fancy name for that is now ‘service learning,’” he says, smiling, and perhaps thinking of summers long ago. “Lots of hands-on conservation.”

This year, then, as Hog Island celebrates its 75th anniversary, its campers will do essentially the same thing Steve Kress once did, and the same thing his efforts have helped people all over the world do: see birds where once they would have seen nothing.

And here in the lobby of the Cornell Lab, on a cloudy Tuesday evening in early April, some of those people, all members of his Spring Field Ornithology class, are gathering for a field trip.

But Steve Kress isn’t here. The group leaders for the night’s owling session are experienced and perfectly capable of operating without him, but as they assemble, they can’t help wondering where the course’s instructor is.

“He’s not coming,” a newcomer reports at last. “His voice is shot, and he’s saving it for the lecture tomorrow night.”

The leaders nod, cluster together, and start organizing their student groups and itineraries for the night. Steve Kress remains elsewhere, saving something that isn’t there, and hoping it will be in the future.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you