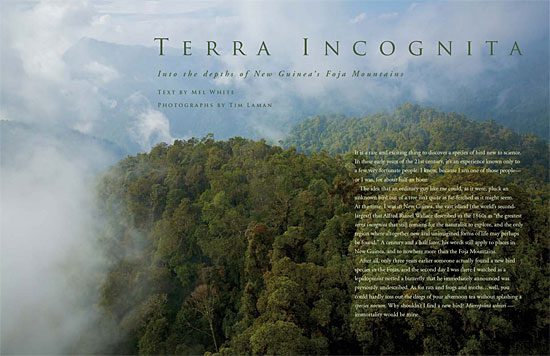

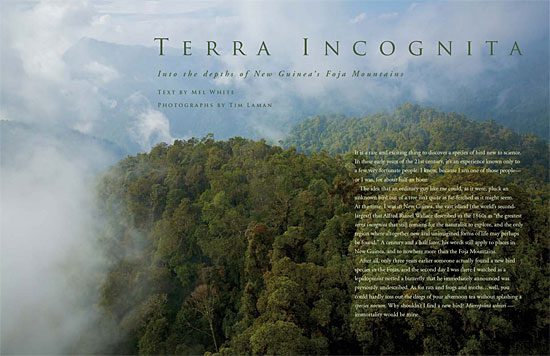

Terra Incognita: Into the Depths of New Guinea’s Foja Mountains

By Mel White; Photographs by Tim Laman

January 15, 2012

It is a rare and exciting thing to discover a species of bird new to science. In these early years of the 21st century, it’s an experience known only to a few very fortunate people. I know, because I am one of those people— or I was, for about half an hour.

The idea that an ordinary guy like me could, as it were, pluck an unknown bird out of a tree isn’t quite as far-fetched as it might seem. At the time, I was in New Guinea, the vast island (the world’s second largest) that Alfred Russel Wallace described in the 1860s as “the greatest terra incognita that still remains for the naturalist to explore, and the only region where altogether new and unimagined forms of life may perhaps be found.” A century and a half later, his words still apply to places in New Guinea, and to nowhere more than the Foja Mountains.

After all, only three years earlier someone actually found a new bird species in the Fojas, and the second day I was there I watched as a lepidopterist netted a butterfly that he immediately announced was previously undescribed. As for rats and frogs and moths…well, you could hardly toss out the dregs of your afternoon tea without splashing a species novum. Why shouldn’t I find a new bird? Micropsitta whitei — immortality would be mine.

Northern New Guinea is dotted with small mountain ranges rising like islands in a sea of lowland rainforest. In fact, these ranges once were islands. Over millions of years, as tectonic plates collided in slow motion, several island groups joined with—accreted to, as geologists say—the New Guinea mainland. Ecologically isolated, these highlands have seen the evolution of scores of endemic species; rugged and remote, many of them have resisted scientific exploration.

The Foja Mountains lie in the Indonesian province of Papua, which comprises most of the western half of New Guinea. (An independent nation, confusingly named Papua New Guinea, occupies the eastern half.) Covered in dense forest, with deep canyons, sheer cliffs, and knife-edge ridges, the Fojas remained unexplored by scientists until the 1980s, when biologist Jared Diamond made forays into the wilderness. His brief surveys were enough to reveal the potential wealth of new species in the Fojas. Diamond also was the first to find the breeding grounds of the Golden-fronted Bowerbird, a species previously known only from ancient museum skins.

It’s hardly surprising that the forbidding Fojas—more than 100 miles from any road, surrounded by lowlands that rank among the world’s top malarial hotspots—have been mostly a blank space on the scientific map. Far more astounding is the lack of evidence that humans have ever inhabited, or even hunted in, the Fojas. The indigenous people living nearby found it far easier to follow rivers or trails around the range rather than struggle across the harsh terrain, which rises to more than 7,400 feet. If any place deserves to be called virgin rainforest, it’s the Fojas.

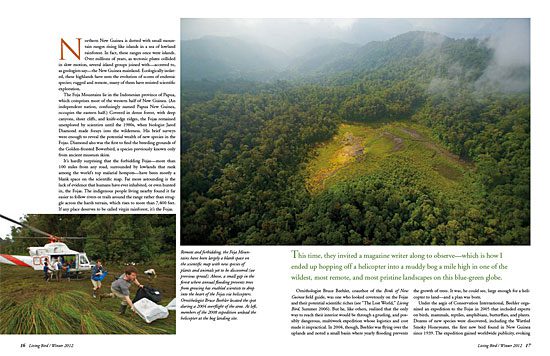

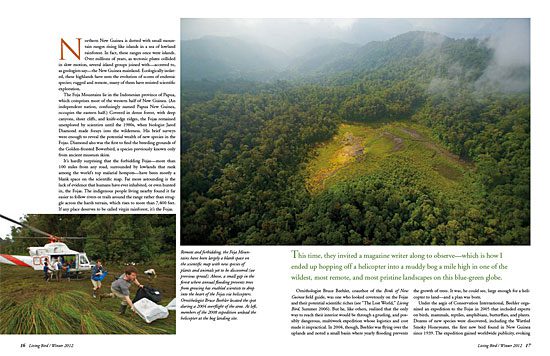

Ornithologist Bruce Beehler, coauthor of the Birds of New Guinea field guide, was one who looked covetously on the Fojas and their potential scientific riches (see “The Lost World,” Living Bird, Summer 2006). But he, like others, realized that the only way to reach their interior would be through a grueling, and possibly dangerous, multiweek expedition whose logistics and cost made it impractical. In 2004, though, Beehler was flying over the uplands and noted a small basin where yearly flooding prevents the growth of trees. It was, he could see, large enough for a helicopter to land—and a plan was born.

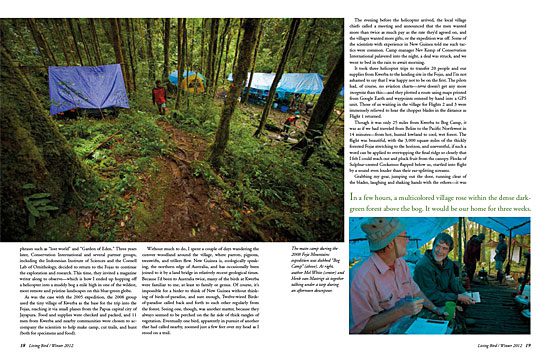

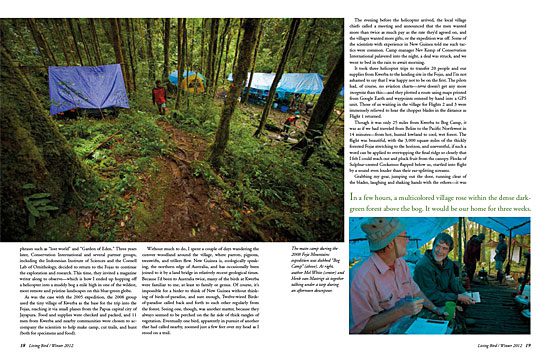

Under the aegis of Conservation International, Beehler organized an expedition to the Fojas in 2005 that included experts on birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, butterflies, and plants. Dozens of new species were discovered, including the Wattled Smoky Honeyeater, the first new bird found in New Guinea since 1939. The expedition gained worldwide publicity, evoking phrases such as “lost world” and “Garden of Eden.” Three years later, Conservation International and several partner groups, including the Indonesian Institute of Sciences and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, decided to return to the Fojas to continue the exploration and research. This time, they invited a magazine writer along to observe—which is how I ended up hopping off a helicopter into a muddy bog a mile high in one of the wildest, most remote and pristine landscapes on this blue-green globe.

As was the case with the 2005 expedition, the 2008 group used the tiny village of Kwerba as the base for the trip into the Fojas, reaching it via small planes from the Papua capital city of Jayapura. Food and supplies were checked and packed, and 11 men from Kwerba and nearby communities were chosen to accompany the scientists to help make camp, cut trails, and hunt (both for specimens and food).

Without much to do, I spent a couple of days wandering the cutover woodland around the village, where parrots, pigeons, treeswifts, and trillers flew. New Guinea is, ecologically speaking, the northern edge of Australia, and has occasionally been joined to it by a land bridge in relatively recent geological times. Because I’d been to Australia twice, many of the birds at Kwerba were familiar to me, at least to family or genus. Of course, it’s impossible for a birder to think of New Guinea without thinking of birds-of-paradise, and sure enough, Twelve-wired Birds-of-paradise called back and forth to each other regularly from the forest. Seeing one, though, was another matter, because they always seemed to be perched on the far side of thick tangles of vegetation. Eventually one bird, apparently in pursuit of another that had called nearby, zoomed just a few feet over my head as I stood on a trail.

The evening before the helicopter arrived, the local village chiefs called a meeting and announced that the men wanted more than twice as much pay as the rate they’d agreed on, and the villages wanted more gifts, or the expedition was off. Some of the scientists with experience in New Guinea told me such tactics were common. Camp manager Nev Kemp of Conservation International palavered into the night, a deal was struck, and we went to bed in the rain to await morning.

It took three helicopter trips to transfer 20 people and our supplies from Kwerba to the landing site in the Fojas, and I’m not ashamed to say that I was happy not to be on the first. The pilots had, of course, no aviation charts—terra doesn’t get any more incognita than this—and they plotted a route using maps printed from Google Earth and waypoints entered by hand into a GPS unit. Those of us waiting in the village for Flights 2 and 3 were immensely relieved to hear the chopper blades in the distance as Flight 1 returned.

Though it was only 25 miles from Kwerba to Bog Camp, it was as if we had traveled from Belize to the Pacific Northwest in 14 minutes—from hot, humid lowland to cool, wet forest. The flight was beautiful, with the 3,000 square miles of the thickly forested Fojas stretching to the horizon, and uneventful, if such a word can be applied to overtopping the final ridge so closely that I felt I could reach out and pluck fruit from the canopy. Flocks of Sulphur-crested Cockatoos flapped below us, startled into flight by a sound even louder than their ear-splitting screams.

Grabbing my gear, jumping out the door, running clear of the blades, laughing and shaking hands with the others—it was all a blur, and then the roar of the copter faded away, and there we were: 130 miles from a city with nice hotels and Wi-Fi and karaoke bars, and yet in practical terms in another world.

But maybe I exaggerate. We had two satellite phones that worked much of the time. We had two generators, electric lights, solar chargers, various electronic gadgets, a kerosene-powered cookstove, and sacks of food ranging from instant coffee to peanut butter to canned meat and vegetables to rice (and rice and rice). And we had the knowledge of the men from the local tribes, whose skills in the forest seemed supernatural, especially their ability to track animals and hunt with bow and arrow. Using only machetes, saplings, and vines, they quickly erected frameworks for sheltering tarps. In a few hours a multicolored village rose within the dense forest above the bog. It would be our home for three weeks.

New Guinea’s wet hill country is its center of bird species richness. At just over 5,400 feet in elevation, Bog Camp was above that zone. My list for the Fojas of birds I saw and satisfactorily identified totaled only 47—not including Kwerba, heard birds, birds found in mist nets, or birds I ate. The entire expedition list, including heard birds and species collected that no one saw except in hand, was only about 90. But what an odd and wonderful bunch they were.

Among the first birds I saw around camp were a pair of Black Pitohuis, members of a justly famed, or infamous, genus. In the 1990s, scientists discovered that some of the six species of Pitohui are poisonous, carrying in their feathers and skin the same deadly batrachotoxins found in some South American poison-dart frogs. Researchers believe that the poison derives from certain insects the pitohuis eat and that they somehow incorporate the toxins into their bodies without killing themselves in the process. The Black Pitohui isn’t known to be as poisonous as its cousins the Hooded and Variable; the degree of toxicity varies among individuals of all species depending on diet.

Okay, a poisonous bird. Not only are we not in Kansas anymore, we’re not even in Australia or Java or Borneo.

The Fojas being on the Australian side of Wallace’s Line, honeyeaters made up a significant part of the local avifauna. The loud, harsh calls of the big Cinnamon-browed Melidectes were a common sound around camp, and bright, beautiful Red-collared Myzomelas were constantly flitting and twittering overhead.

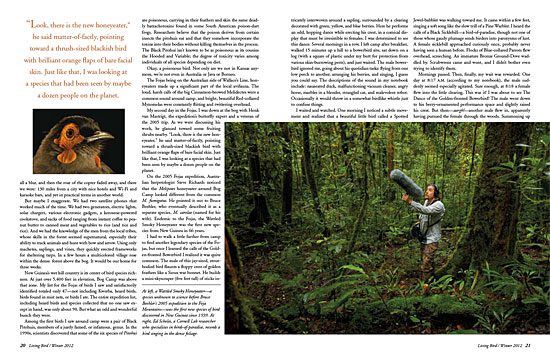

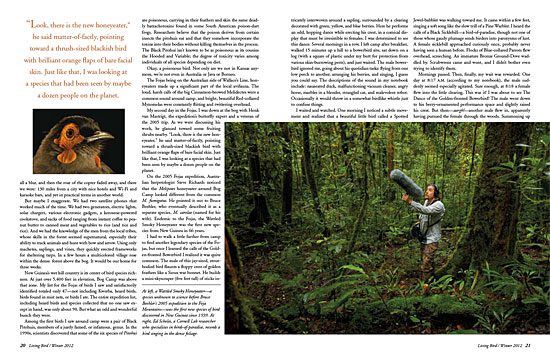

My second day in the Fojas, I was down at the bog with Henk van Mastrigt, the expedition’s butterfly expert and a veteran of the 2005 trip. As we were discussing his work, he glanced toward some fruiting shrubs nearby. “Look, there is the new honeyeater,” he said matter-of-factly, pointing toward a thrush-sized blackish bird with brilliant orange flaps of bare facial skin. Just like that, I was looking at a species that had been seen by maybe a dozen people on the planet.

On the 2005 Fojas expedition, Australian herpetologist Steve Richards noticed that the Melipotes honeyeater around Bog Camp looked different from the common M. fumigatus. He pointed it out to Bruce Beehler, who eventually described it as a separate species, M. carolae (named for his wife). Endemic to the Fojas, the Wattled Smoky Honeyeater was the first new species from New Guinea in 66 years.

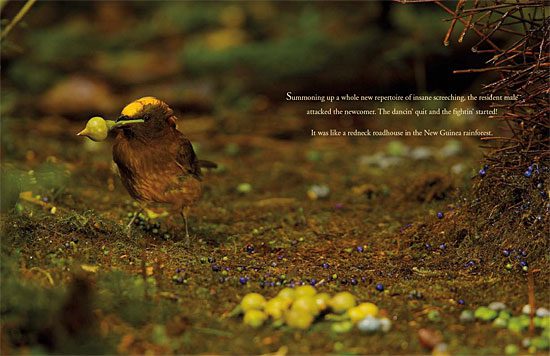

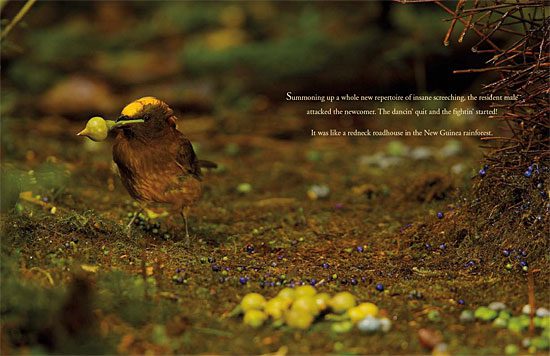

I had to walk a little farther from camp to find another legendary species of the Fojas, but once I learned the calls of the Golden- fronted Bowerbird I realized it was quite common. The male of this jay-sized, stout-bodied bird flaunts a floppy crest of golden feathers like a Sioux war bonnet. He builds a mini-skyscraper (five feet tall) of sticks intricately interwoven around a sapling, surrounded by a clearing decorated with green, yellow, and blue berries. Here he performs an odd, hopping dance while erecting his crest, in a comical display that must be irresistible to females. I was determined to see this dance. Several mornings in a row, I left camp after breakfast, walked 15 minutes up a hill to a bowerbird site, sat down on a log (with a square of plastic under my butt for protection from various skin-burrowing pests), and just waited. The male bowerbird ignored me, going about his quotidian tasks: flying from one low perch to another, arranging his berries, and singing, I guess you could say. The descriptions of the sound in my notebook include: nauseated duck, malfunctioning vacuum cleaner, angry horse, marbles in a blender, strangled cat, and malevolent robot. Occasionally it would throw in a somewhat birdlike whistle just to confuse things.

I waited and watched. One morning I noticed a subtle movement and realized that a beautiful little bird called a Spotted Jewel-babbler was walking toward me. It came within a few feet, singing a soft song like the slow trill of a Pine Warbler. I heard the calls of a Black Sicklebill—a bird-of-paradise, though not one of those whose gaudy plumage sends birders into paroxysms of lust. A female sicklebill approached curiously once, probably never having seen a human before. Flocks of Blue-collared Parrots flew overhead, screeching. An immature Bronze Ground-Dove waddled by. Scrubwrens came and went, and I didn’t bother even trying to identify them.

Mornings passed. Then, finally, my wait was rewarded. One day at 8:17 A.M. (according to my notebook), the male suddenly seemed especially agitated. Sure enough, at 8:18 a female flew into the little clearing. This was it! I was about to see The Dance of the Golden-fronted Bowerbird! The male went down to his berry-ornamented performance space and slightly raised his crest. But then—aargh!—another male flew in, apparently having pursued the female through the woods. Summoning up a whole new repertoire of insane screeching, the resident male attacked the newcomer. The dancin’ quit and the fightin’ started! It was like a redneck roadhouse in the New Guinea rainforest.

All three birds flew downhill and disappeared. Five minutes later the first male returned, before leaving again briefly to chase away the second male, which I could hear calling somewhere in the vicinity. By 8:43, the first male was back to his routine, arranging his sticks and berries and calling, romantically hopeful once again I suppose. And I said to heck with it, or words to that effect.

One day, three of the local men walked into camp carrying an immature Dwarf Cassowary, which they’d shot with a bow and arrow. Christopher Milensky, collecting birds for the Smithsonian Institution, was highly excited to have a specimen of this little-known species. As its name implies, it’s a smaller version of the Southern Cassowary, the flightless struthioniform (ostrich relative) found in New Guinea and in Queensland, Australia. Chris was eager to pickle the whole bird and try to get it back to the United States. The hunters had other ideas, though, and made it clear that while Chris could have the skeleton, the flesh was theirs.

“Here we see the dichotomy between scientists who want to preserve the specimen and guys who just want to eat it ASAP,” Chris said. We’d already learned that most of the local men classified animals into two categories, edible and inedible, and truly couldn’t imagine why anyone would care about the latter.

The night breeze was soon filled with the aroma of frying cassowary. I ate a couple of pieces, but “well-done” doesn’t begin to describe the locally preferred cooking method. I can, however, now casually drop “tastes like cassowary” into dinner talk when the conversation drags. How many people could dispute me?

I can’t put Dwarf Cassowary on my life list, though. I never saw one, despite hearing them crashing away through the bushes several times as I was walking trails. Their scat, filled with big forest fruits, was abundant. It looked like somebody had puked pink and purple Ping-Pong balls.

Did I mention it rained? Did I mention that after two initial days of misleadingly nice weather, the rainy season arrived November 8 with the subtlety of a dam bursting? It rained every day, hours and hours, torrentially, and just when you thought it couldn’t possibly rain any harder it did, so loud on the tarps you had to shout to make yourself heard at dinner.

The bad news was that the helicopter landing site in the bog was quickly under five feet of water. The men cleared a new site. Within days it, too, was submerged. The idea that we might be stuck here until, say, May, exhausting our food and forced to fight cassowaries for fruit, crossed my mind, when I wasn’t wondering whether there’s such a thing as a pontoon helicopter.

The good news was that a pair of Salvadori’s Teal, a rarish duck endemic to New Guinea, showed up in the newly created lake and stayed for the rest of our time there. We could admire their beauty as we sat on the bank, checking a marker stick to see how far the water had risen overnight.

People were doing actual work, of course, between and during the downpours. Ed Scholes of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, one of the world’s foremost experts on birds-of-paradise, was hoping to prove that the version of the Carola’s Parotia in the Fojas should be split as a separate species. I followed him a few times on his treks into the forest as he set up his high-definition cameras with motion-sensing triggers at courtship sites. No one could have worked harder than he did, yet the males hadn’t felt like performing their distinctive dance.

Toward the end of the trip he returned one evening and sat down dejectedly.

“I’m up to a ratio of four hundred to one,” he said. “Four hundred minutes of sitting in that mosquito-infested pigsty of a blind to one minute of seeing the bird. It’s definitely the longest I’ve ever spent in a blind for so little result.

“I got video of the male parotia, but I didn’t document the courtship behavior that would help confirm it’s a different species. And when you think about where this bird lives…” He shook his head. “The odds are I won’t have another chance, and neither will anyone else. It’s not going to happen in my lifetime.”

Ed was one to whom I had mentioned my sightings of a tiny parrot that I couldn’t match with anything in the Beehler field guide. The first time had been at a ridgetop overlook near my bowerbird vigil site, the only place near camp with a long-distance view over the Fojas. As I stood there, a pair of very small greenish parrots busied themselves feeding on the trunk of a tree just a few feet away. I made some quick notes. (I was also, as I recall, seeing my first Canary Flycatcher and Buff-faced Scrubwren at more or less the same time.) Later, I looked up the parrot—or tried to. It resembled a Red-breasted Pygmy-Parrot, but it had lots of yellow on the head. The birds I’d seen were very different from the illustration in the field guide.

Maybe I was hallucinating from tainted wallaby meat or something. But then a few days later, as I sat in a favorite little cove where I’d seen several good birds, I got a quick glimpse of what seemed to be the same diminutive parrot— with yellow on the head, no question.

Every birder has heard a beginner describe some unknown sighting, usually with the phrase, “It didn’t match anything in the book.” And we nod politely and refrain from saying, “It didn’t match anything in the book because you didn’t see what you think you did. There ain’t no such bird.”

Which is why I didn’t press my observations too strongly on Ed or Nev Kemp or Chris Milensky or whomever else I mentioned them to. I had no photographs; I’d been alone. No one else had seen this little bird. Who was I to claim there was an undescribed pygmy-parrot flying around the Fojas? But I knew what I had seen.

(Actually, Nev was in the same predicament. Several times he saw an unknown pigeon of the Ducula genus while out by himself, and he even carried the expedition’s air rifle for a couple of days with the intention of collecting one, to no avail.)

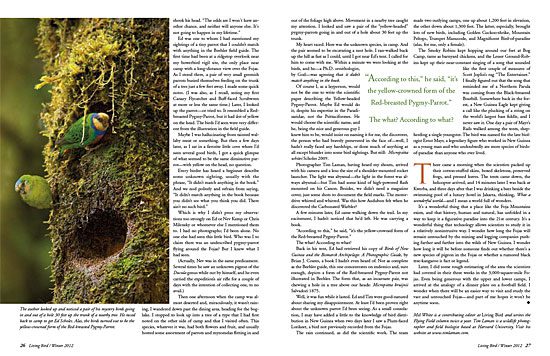

Then one afternoon when the camp was almost deserted and, miraculously, it wasn’t raining, I wandered down past the dining area, heading for the boglake. I stopped to look up into a tree of a type that I had first noted on the other side of camp and that I visited often. This species, whatever it was, had both flowers and fruit, and usually hosted some assortment of parrots and myzomelas flitting in and out of the foliage high above. Movement in a nearby tree caught my attention. I looked and saw a pair of the “yellow-headed” pygmy-parrots going in and out of a hole about 30 feet up the trunk.

My heart raced. Here was the unknown species, in camp. And the pair seemed to be excavating a nest hole. I ran-walked back up the hill as fast as I could, until I got near Ed’s tent. I called for him to come with me. Within a minute we were looking at the birds, and he—a Ph.D. ornithologist, by God—was agreeing that it didn’t match anything in the book.

Of course I, as a layperson, would not be the one to write the scientific paper describing the Yellow-headed Pygmy-Parrot. Maybe Ed would do it, despite his expertise in the Paradisaeidae, not the Psittaciformes. He would choose the scientific name, and he, being the nice and generous guy I knew him to be, would insist on naming it for me, the discoverer, the person who had bravely persevered in the face of—well, I hadn’t really faced any hardships, or done much of anything at all except blunder into some bird sightings. But still: Micropsitta whitei Scholes 2009.

Photographer Tim Laman, having heard my shouts, arrived with his camera and a lens the size of a shoulder-mounted rocket launcher. The light was abysmal—the light in the forest was always abysmal—but Tim had some kind of high-powered flash mounted on his Canon. Besides, we didn’t need a magazine cover, just some shots to document the field marks. The motordrive whirred and whirred. Was this how Audubon felt when he discovered the Carbonated Warbler?

A few minutes later, Ed came walking down the trail. In my excitement, I hadn’t noticed that he’d left. He was carrying a book.

“According to this,” he said, “it’s the yellow-crowned form of the Red-breasted Pygmy-Parrot.”

The what? According to what?

Back in his tent, Ed had retrieved his copy of Birds of New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago: A Photographic Guide, by Brian J. Coates, a book I hadn’t even heard of. Not as complete as the Beehler guide, this one concentrates on endemics and, sure enough, depicts a form of the Red-breasted Pygmy-Parrot not illustrated in Beehler. The form that, as an incarnate pair, was chewing a hole in a tree above our heads: Micropsitta bruijniiSalvadori 1875.

Well, it was fun while it lasted. Ed and Tim were good-natured about sharing my disappointment. At least I’d been proven right about the unknown parrot I’d been seeing. As a small consolation, I may have added a little to the knowledge of bird distribution in New Guinea when two days later I saw a Plum-faced Lorikeet, a bird not previously recorded from the Fojas.

The rain continued, as did the scientific work. The team made two outlying camps, one up about 1,200 feet in elevation, the other down about 1,300 feet. The latter, especially, brought lots of new birds, including Golden Cuckoo-shrike, Mountain Peltops, Trumpet Manucode, and Magnificent Bird-of-paradise (alas, for me, only a female).

The Smoky Robins kept hopping around our feet at Bog Camp, tame as barnyard chickens, and the Lesser Ground-Robins kept up their near-constant singing of a song that sounded like the first couple of measures of Scott Joplin’s rag “The Entertainer.” I finally figured out that the song that reminded me of a Northern Parula was coming from the Black-breasted Boatbill. Somewhere back in the forest, a New Guinea Eagle kept giving a call like the plucking of a string on the world’s largest bass fiddle, and I never saw it. One day a pair of Mayr’s Rails walked among the tents, shepherding a single youngster. The bird was named for the late biologist Ernst Mayr, a legendary figure who worked in New Guinea as a young man and who undoubtedly ate more species of birds-of- paradise than anyone who ever lived.

There came a morning when the scientists packed up their cotton-stuffed skins, boxed skeletons, preserved frogs, and pressed leaves. The tents came down, the helicopter arrived, and 14 minutes later I was back at Kwerba, and three days after that I was drinking a beer beside the swimming pool of a luxury hotel in Jakarta, thinking, What a wonderful world—and I mean a world full of wonders.

It’s a wonderful thing that a place like the Foja Mountains exists, and that history, human and natural, has unfolded in a way to keep it a figurative paradise into the 21st century. It’s a wonderful thing that technology allows scientists to study it in a relatively nonintrusive way. I wonder how long the Fojas will remain untouched by the mining and logging companies pushing farther and farther into the wilds of New Guinea. I wonder how long it will be before someone finds out whether there’s a new species of pigeon in the Fojas or whether a rumored black tree-kangaroo is fact or legend.

Later, I did some rough estimating of the area the scientists had covered in their three weeks in the 3,000-square-mile Fojas. Even being generous with the upper and lower camps, I arrived at the analogy of a dinner plate on a football field. I wonder when there will be an easier way to visit and study the vast and untouched Fojas—and part of me hopes it won’t be anytime soon.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you