You Must Believe in Spring, and Spring Field Ornithology

By Peter Cashwell; Photographs by Marie Read

January 15, 2012

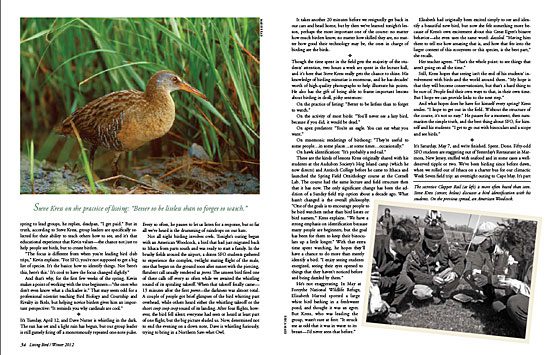

It is Saturday, March 26, 2011, nearly a week after the vernal equinox, and we’re freezing. Everyone’s hat is pulled low, and there’s a bit of dancing from foot to foot to generate warmth as Meena, the leader assigned to guide Group Three for the day, sets up her spotting scope on the roadside. With the sun barely over the horizon and a northerly wind howling at us over the open expanse of Ithaca Airport, not one among the six of us feels there is anything spring-like about this, the first outing of our Spring Field Ornithology (SFO) class.

First offered by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in 1976, this eight-week noncredit public education course has become an Ithaca institution. The other members of Group Three look as if they agree that anyone out on a morning like this belongs in an institution, but we are nonetheless gamely joining a cohort of considerable size and vintage. In this, the 35th SFO class (one spring was skipped several decades back), there are 137 students enrolled in the lecture and/or field trip sections. Counting the repeat customers—quite a few students migrate back after the first spring—SFO alumni now number well over 2,000. Perhaps even more remarkable is that the course has been taught every spring by the same person: Steve Kress.

Though famed as the founder of Project Puffin, the Audubon seabird restoration initiative, Kress may be best known in his hometown for bringing birds to the community every spring. On Wednesday nights he takes over the auditorium at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to share the fine points of ornithology with birders of every ability level. It’s something of a challenge to keep students of such varying experience interested in the same presentation, but Kress handles the job with a calm confidence and a dry sense of humor. Whether he’s demonstrating the irregular Morse-code-like tapping of a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker or showing the map of the astonishing trans-Pacific migrations of the Bar-tailed Godwit, he has the class in the palm of his hand.

On weekend field trips, though, he opens his hands, releasing the students into the care of his group leaders. Some of the leaders—such as the droll, patient sparrow expert Wes Hochachka— work at the Lab of Ornithology; others, such as the sagacious and relentless Dave Nutter, used to work at the Lab; still others—such as David Nicosia, a meteorologist by trade—are former SFO students. The students come from backgrounds as varied as their leaders: retirees, professors, merchants, scientists, homemakers, Ithaca natives, and commuters from more than an hour away, all eager to learn what the “field” in Spring Field Ornithology really means.

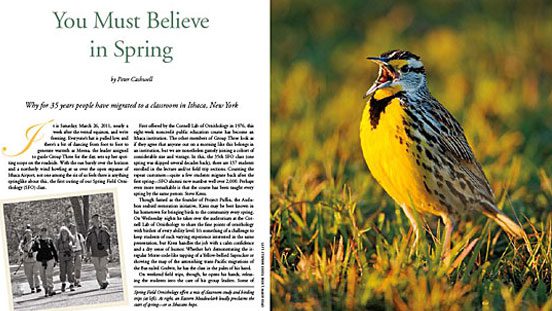

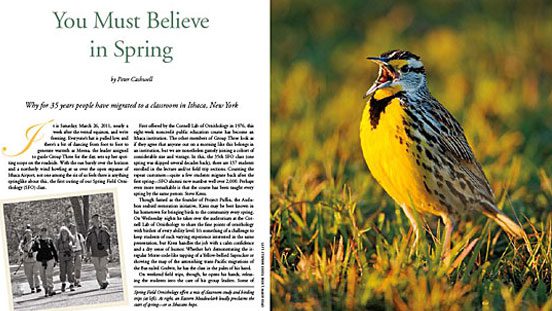

Out in the field where Group Three is standing, the temperature is hovering at about 20 degrees Fahrenheit, not counting the wind chill. Our purpose is to look for what we hope will be the first Eastern Meadowlark of 2011, but I can’t be the only person wondering, Why a meadowlark? Though handsome enough, it is in no way rare; people see meadowlarks in Ithaca every year, once they arrive from their wintering grounds.

The importance of this bird is twofold. First, it gives Meena a chance to demonstrate the importance of learning a bird’s song as well as its appearance. The Eastern Meadowlark’s slurred whistle is a distinctive one; to remember it, she uses the mnemonic, “Spring is here.”

And that’s the second reason for this bird’s importance. In the South, where I was born and raised, winter can be unpleasant or even dangerous, but its end is never in doubt. Though we may get a flurry in early March, the trees are always well on their way to full leafing by St. Patrick’s Day, and the arrival of spring migrants is viewed as a pleasant surprise—sure, we knew they were coming at some point, but we hadn’t really thought about the matter much.

Here in New York’s Finger Lakes region, they’ve thought about it. From the first meaningful snowfall in November through the grim darkness of December, through months of January and all the godforsaken days of February…oh, yes, they’ve thought about it. One document given to each student at the first SFO lecture is a document titled “Average Spring Arrival Dates.” It lists 72 migrant species and when to expect them in the area, starting on March 5 (Wood Duck) and ending on April 28 (Wood Thrush). An Ithaca birder needs this printed reinforcement, because here spring is a matter of belief: to get through the winter, you must keep your faith that it will end, the sun will come out again, and the bright birds of summer will return to the shores of Cayuga Lake.

That, in a nutshell, is what we are doing in this field: looking not just for a bird but for renewal. We can see new things, develop new skills, and experience new growth. And when Meena hears the slurred whistle that signals the meadowlark’s presence, you can see it in her eyes: this,this is what we’re here to learn.

Robyn Bailey hasn’t been in Ithaca long. An Alabama native with one degree in biology and another in fisheries and wildlife, she arrived here in the dead of winter. Despite the unfamiliar intensity and duration of the cold weather, however, she has good reasons for enrolling in the SFO course. One is professional; she works in the Cornell Lab and though she’s been birding for five or six years, she wants more experience. “It’s important to continue refining field skills, especially as an ornithologist,” she says. The most important piece of knowledge, in her estimation, has been the course’s discussion of sounds. “Steve’s coverage of woodpeckers, of vocalizations and drumming patterns, has cued me into several resources and mnemonics,” Robyn says. “It’s really the next level of birding as a hobby and a profession.”

At the same time, the course is also a social opportunity, helping her meet more people in the birding community of her new hometown, as well as learning about local hotspots she couldn’t find on her own. “The biggest draw is the field trips,” Robyn says. “I need that collective experience in which back road to take or which pond will have a special bird on it.”

With a new place, new birds, and new people, the course has definitely been a learning experience for Robyn. “Even though I work at the Lab,” she notes, “I’m taking the role of student— advanced intermediate student.”

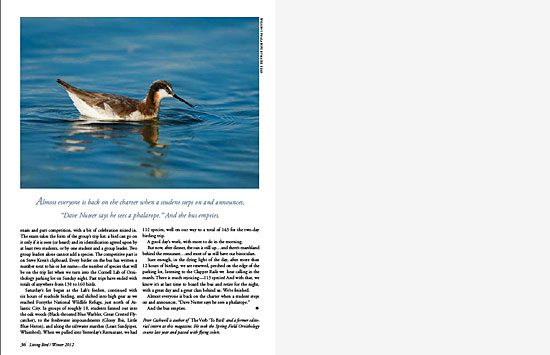

It’s Saturday, April 2, a much warmer and sunnier morning, and Bob McGuire has brought Group Three to Myers Point on Cayuga Lake to look for migratory waterfowl, which take up the majority of the class’s attention during the first few weeks. On our first approach to a local marina, we spotted a trio of Pied-billed Grebes, but they have now vanished into the shadows of the docks. We’ve begun the identification of a trio of Ring-necked Ducks at the far end when the full dozen of us are brought up short by a cry from the open water. It’s not exactly beautiful, not exactly raucous, but we jerk upright as though by reflex.

Bob knows perfectly well what it is, but he doesn’t say. He’s an instructor, determined to let us make the call based on our own observations. Anytime we get a bird in our binoculars, he demands that we call out field marks rather than species names. This practice allows us to assemble a lengthy list of traits before we attempt to identify a bird, and it also prevents us from making invalid assumptions just because someone has mentioned a particular species. He’s also particular about the use of size as a field mark, unless we have a clear standard of measurement visible.

The mirror-bright waters are covered with small diving ducks, mostly Buffleheads, but we’re all determined to spot the source of that call. And in a few moments, Bob has his scope on it, barreling northward only a few feet above the water. He calls out field marks, the way he’s taught us, rather than naming the species. “Dark bird, flying fast…I shouldn’t say this, but it’s a BIG bird… the feet are trailing behind.”

It’s the first time I’ve ever seen the Common Loon in its breeding plumage, but nothing is going to replace the memory of that call.

Kevin McGowan, like Bob, is a group leader. He is also a professional ornithologist and former Sapsucker (the Cornell Lab’s World Series of Birding team), who teaches several of the Lab’s home study courses. His passion is corvids, which to some degree limits his participation in the SFO course; after the first few weekends, he’s invested in his research on crows during their breeding season. When asked why he continues to make the time in the spring to lead groups, he replies, deadpan, “I get paid.” But in truth, according to Steve Kress, group leaders are specifically selected for their ability to teach others how to see, and it’s that educational experience that Kevin values—the chance not just to help people see birds, but to create birders.

“The focus is different from when you’re leading bird club trips,” Kevin explains. “For SFO, you’re not supposed to get a big list of species. It’s the basics: how to identify things. Not ‘here’s this, here’s this.’ It’s cool to have the focus changed slightly.” And that’s why, for the first few weeks of the spring, Kevin makes a point of working with the true beginners—“the ones who don’t even know what a chickadee is.” That may seem odd for a professional scientist teaching Bird Biology and Courtship and Rivalry in Birds, but helping novice birders gives him an important perspective: “It reminds you why cardinals are cool.”

It’s Tuesday, April 12, and Dave Nutter is whistling in the dark. The sun has set and a light rain has begun, but our group leader is still gamely firing off a monotonously repeated one-note pulse. Every so often, he pauses to let us listen for a response, but so far all we’ve heard is the drumming of raindrops on our hats.

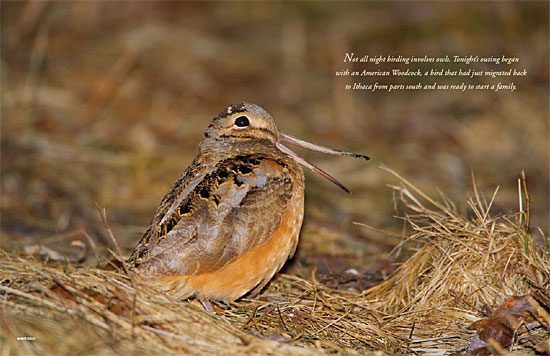

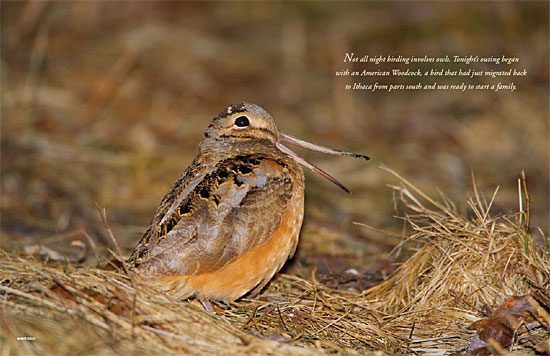

Not all night birding involves owls. Tonight’s outing began with an American Woodcock, a bird that had just migrated back to Ithaca from parts south and was ready to start a family. In the brushy fields around the airport, a dozen SFO students gathered to experience the complex, twilight mating flight of the male, one that began on the ground soon after sunset with the piercing, flatulent call usually rendered as peent. The unseen bird fired one of these calls off every so often while we awaited the whistling sound of its spiraling takeoff. When that takeoff finally came— 13 minutes after the first peent—the darkness was almost total. A couple of people got brief glimpses of the bird whirring past overhead, while others heard either the whistling takeoff or the short coop coop coop sound of its landing. After four flights, however, the bird fell silent; everyone had seen or heard at least part of one flight, but the big picture eluded us. Now, determined not to end the evening on a down note, Dave is whistling furiously, trying to bring in a Northern Saw-whet Owl.

It takes another 20 minutes before we resignedly get back in our cars and head home, but by then we’ve learned tonight’s lesson, perhaps the most important one of the course: no matter how much birders know, no matter how skilled they are, no matter how good their technology may be, the ones in charge of birding are the birds.

Though the time spent in the field gets the majority of the students’ attention, two hours a week are spent in the lecture hall, and it’s here that Steve Kress really gets the chance to shine. His knowledge of birding minutiae is enormous, and he has decades’ worth of high-quality photographs to help illustrate his points. He also has the gift of being able to frame important lessons about birding in droll, pithy sentences:

On the practice of listing: “Better to be listless than to forget to watch.”

On the activity of most birds: “You’ll never see a lazy bird, because if you did, it would be dead.”

On apex predators: “You’re an eagle. You can eat what you want.”

On mnemonic renderings of birdsong: “They’re useful to some people…in some places…at some times…occasionally.”

On hawk identification: “It’s probably a red-tail.”

These are the kinds of lessons Kress originally shared with his students at the Audubon Society’s Hog Island camp (which he now directs) and Antioch College before he came to Ithaca and launched the Spring Field Ornithology course at the Cornell Lab. The course had the same lecture and field structure then that it has now. The only significant change has been the addition of a Sunday field trip option about a decade ago. What hasn’t changed is the overall philosophy. “One of the goals is to encourage people to be bird watchers rather than bird listers or bird namers,” Kress explains. “We have a strong emphasis on identification because many people are beginners, but the goal has been for them to keep their binoculars up a little longer.” With that extra time spent watching, he hopes they’ll have a chance to do more than merely identify a bird. “I enjoy seeing students energized, seeing their eyes opened to things that they haven’t noticed before and being dazzled by them.”

He’s not exaggerating. In May at Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, Elisabeth Harrod spotted a large white bird bathing in a freshwater pond, and thought it was an egret. But Kress, who was leading the group, wasn’t sure at first: “It struck me as odd that it was in water to its breast—I’d never seen that before.”

Elisabeth had originally been excited simply to see and identify a beautiful new bird, but now she felt something more because of Kress’s own excitement about this Great Egret’s bizarre behavior—she even uses the same word: dazzled. “Having him there to tell me how amazing that is, and how that fits into the larger context of this ecosystem or this species, is the best part,” she recalls.

Her teacher agrees. “That’s the whole point: to see things that aren’t going on all the time.”

Still, Kress hopes that seeing isn’t the end of his students’ involvement with birds and the world around them. “My hope is that they will become conservationists, but that’s a hard thing to be sure of. People find their own ways to that, in their own time. But I hope we can provide links to the next step.”

And what hopes does he have for himself every spring? Kress smiles. “I hope to get out in the field. Without the structure of the course, it’s not so easy.” He pauses for a moment, then summarizes the simple truth, and the best thing about SFO, for himself and his students: “I get to go out with binoculars and a scope and see birds.”

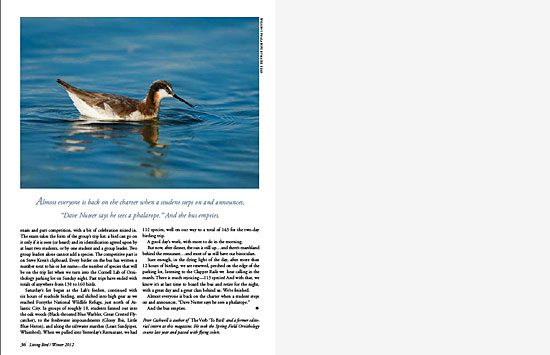

It’s Saturday, May 7, and we’re finished. Spent. Done. Fifty-odd SFO students are staggering out of Yesterday’s Restaurant in Marmora, New Jersey, stuffed with seafood and in some cases a well-deserved tipple or two. We’ve been birding since before dawn, when we rolled out of Ithaca on a charter bus for our climactic Week Seven field trip: an overnight outing to Cape May. It’s part exam and part competition, with a bit of celebration mixed in. The exam takes the form of the group’s trip list; a bird can go on it only if it is seen (or heard) and its identification agreed upon by at least two students, or by one student and a group leader. Two group leaders alone cannot add a species. The competitive part is on Steve Kress’s clipboard. Every birder on the bus has written a number next to his or her name—the number of species that will be on the trip list when we turn into the Cornell Lab of Ornithology parking lot on Sunday night. Past trips have ended with totals of anywhere from 130 to 160 birds.

Saturday’s list began at the Lab’s feeders, continued with six hours of roadside birding, and shifted into high gear as we reached Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, just north of Atlantic City. In groups of roughly 10, students fanned out into the oak woods (Black-throated Blue Warbler, Great Crested Flycatcher), to the freshwater impoundments (Glossy Ibis, Little Blue Heron), and along the saltwater marshes (Least Sandpiper, Whimbrel). When we pulled into Yesterday’s Restaurant, we had 112 species, well on our way to a total of 143 for the two-day birding trip.

A good day’s work, with more to do in the morning.

But now, after dinner, the sun is still up…and there’s marshland behind the restaurant…and most of us still have our binoculars.

Sure enough, in the dying light of the day, after more than 12 hours of birding, we are renewed, perched on the edge of the parking lot, listening to the Clapper Rails we hear calling in the marsh. There is much rejoicing—113 species! And with that, we know it’s at last time to board the bus and retire for the night, with a great day and a great class behind us. We’re finished.

Almost everyone is back on the charter when a student steps on and announces, “Dave Nutter says he sees a phalarope.”

And the bus empties.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you