Last Chance for the World’s Rarest Eagle: Philippine Eagle

Text and photographs by George Oxford Miller

April 15, 2012

Eleven hours of waiting, watching. Yesterday we sat for six hours on a bamboo bench in an intermittent drizzle and scanned a distant slope hoping for a glimpse of the largest, most endangered raptor on the planet, the Philippine Eagle, national bird of the Philippines. Today we’ve been scoping the mountain ridges intently for another five hours, this time in the blazing sun. Soaring Oriental Honey-buzzards and Philippine Serpent-Eagles temporarily get our adrenaline pumping, but they’re only diversions.

Finally, Pete, a fellow bird watcher, yells, “A big, white bird landed in the tree by the cliff.” We had studied the distant slopes for so long we had the landmarks memorized. I focus the scope to 50x and see the object of our quest perched regally in the distant tree about a mile away.

The eagle flies to another tree, and we spot an immature. The adult soon departs as the juvenile bends over and rips pieces from the prey its parent brought and eagerly gulps them down. After its meal, the juvenile flies a short distance to another tree, sits a while, then flies back as though practicing its flying. Transfixed, we spend the next two hours gazing at the bird.

After flying from Manila to Cagayan de Oro on the island of Mindanao, we drove for four hours on a narrow, winding mountain road through remote villages with thatched-roof, bamboo huts, then transferred ourselves and our gear to the back of a four-wheel-drive flatbed truck. Finally, at the end of the muddy road, villagers lashed our luggage onto the backs of some scrawny little horses. We pulled on rubber boots and started a one-hour ascent up a slippery trail, sometimes sloshing through ankle-deep slush, to reach our rustic bird-watching “ecolodge”—a decaying barn with a dormitory loft that had no beds or flush toilets, and only a plastic bucket for bathing.

At that point, we still had another two-hour, rubber-boot hike to reach the eagle-viewing site—a long bench made from split bamboo in a hacked-away clearing in an overgrown potato field that nature has reclaimed. But the view is spectacular, a deep gorge with a hidden river encompassing a long ridge and twin rounded mountains—perfect habitat for the soaring kings of the rainforest.

Nicky Icarangal, our guide with Birding Adventure Philippines, studies the eagle in the scope. “See the white spots on the wings?” he says. “It’s an immature. Philippine Eagles mate for life and take two years to raise a chick. The young take five to seven years to sexually mature. They live about 20 years in the wild. This pair nests up and down the river gorge, so this is one of the most reliable places to see the eagles in the wild. Plus we get a chance to see the mountain endemics that live at this elevation.”

During our hours of idle watching, flocks of small birds dash past to break the monotony. Sparrow-sized Chestnut Munias, a popular cage bird in the pet trade and former national bird of the Philippines, zip into the tall grass. Apo Mynas, black with a brilliant yellow patch of bare skin around their eyes and a fuzzy crest, perch and watch us watch them. The smaller birds are exciting, yet not the reason we flew 7,000 miles and tramped four miles up a muddy trail. But with the first sight of the magnificent eagle, we forget the hardships.

Besides seeing the endangered raptor, we came to plan a fundraiser for the Philippine Eagle Foundation. Located in Davao, the foundation is ground zero for efforts to breed the eagles in captivity and release them to the wild, and also to educate mountain villagers about the bird. A study published in the journal Ibis in 2003 reported that enough habitat exists to support 82 to 239 nesting territories— depending on how the remaining forest on Mindanao is analyzed—and concluded that “the Philippine Eagle probably remains the most important [avian] single-species conservation issue on the planet today.”

David Tomb, a wildlife artist who organized our group of four, previously created life-sized paintings of the Mexican Tufted Jay to raise funds for a wildlife preserve in the oak canyons near Mazatlán (see “A Canyon of Their Own,” Living Bird, Summer, 2009). For the current project, he is planning an exhibit at his San Francisco gallery featuring the Philippine Eagle and other birds of Mindanao to benefit the foundation and its education projects. So seeing the eagle fires our enthusiasm for better reasons than just achieving another check on our life lists.

After a few quick first views, we take turns at the scope for longer studies of the eagle. Then David shouts, “Look! A monkey! Climbing the limb above the eagle!” Again we rush to the scope. The 3-foot-tall raptor with a 7-foot wingspan was formerly known by the more sensational name of Philippine Monkey-eating Eagle, but the juvenile pays no attention to the foolhardy macaque perched above it in the canopy.

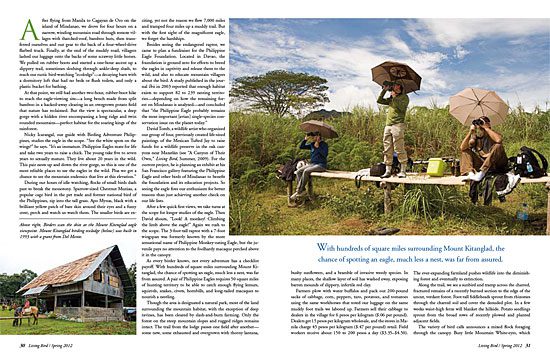

As every birder knows, not every adventure has a checklist payoff. With hundreds of square miles surrounding Mount Kitanglad, the chance of spotting an eagle, much less a nest, was far from assured. A pair of Philippine Eagles requires 50 square miles of hunting territory to be able to catch enough flying lemurs, squirrels, snakes, civets, hornbills, and long-tailed macaques to nourish a nestling.

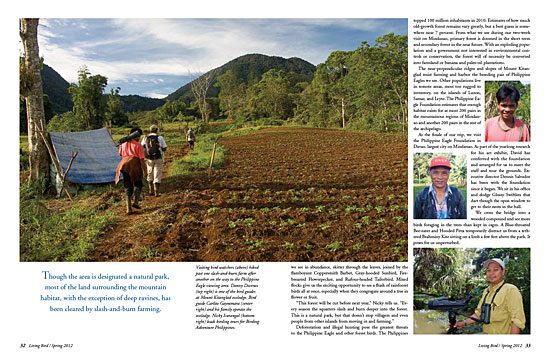

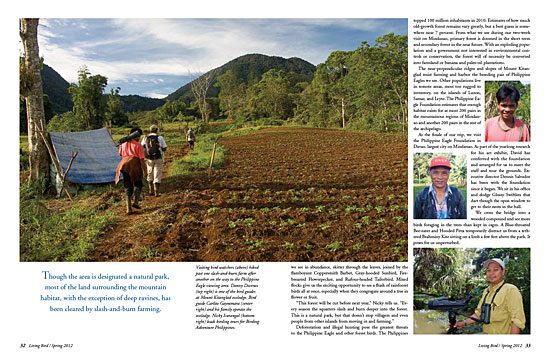

Though the area is designated a natural park, most of the land surrounding the mountain habitat, with the exception of deep ravines, has been cleared by slash-and-burn farming. Only the forest on the steep mountain slopes and rugged ridges remains intact. The trail from the lodge passes one field after another—some new, some exhausted and overgrown with thorny lantana, bushy sunflowers, and a bramble of invasive weedy species. In many places, the shallow layer of soil has washed away, exposing barren mounds of slippery, infertile red clay.

Farmers plow with water buffalos and pack out 200-pound sacks of cabbage, corn, peppers, taro, potatoes, and tomatoes using the same workhorses that toted our luggage on the same muddy foot trails we labored up. Farmers sell their cabbage to dealers in the village for 6 pesos per kilogram ($.06 per pound). Dealers get 15 pesos per kilogram wholesale, and the stores in Manila charge 45 pesos per kilogram ($.47 per pound) retail. Field workers receive about 150 to 200 pesos a day ($3.35–$4.50). The ever-expanding farmland pushes wildlife into the diminishing forest and eventually to extinction.

Along the trail, we see a sunbird and tramp across the charred, fractured remains of a recently burned section to the edge of the uncut, verdant forest. Foot-tall fiddleheads sprout from rhizomes through the charred soil and cover the denuded plot. In a few weeks waist-high ferns will blanket the hillside. Potato seedlings sprout from the broad rows of recently plowed and planted adjacent fields.

The variety of bird calls announces a mixed flock foraging through the canopy. Busy little Mountain White-eyes, which we see in abundance, skitter through the leaves, joined by the flamboyant Coppersmith Barbet, Gray-hooded Sunbird, Fire-breasted Flowerpecker, and Rufous-headed Tailorbird. Mixed flocks give us the exciting opportunity to see a flush of rainforest birds all at once, especially when they congregate around a tree in flower or fruit.

“This forest will be cut before next year,” Nicky tells us. “Every season the squatters slash and burn deeper into the forest. This is a natural park, but that doesn’t stop villagers and even people from other islands from moving in and farming.”

Deforestation and illegal hunting pose the greatest threats to the Philippine Eagle and other forest birds. The Philippines topped 100 million inhabitants in 2010. Estimates of how much old-growth forest remains vary greatly, but a best guess is somewhere near 7 percent. From what we see during our two-week visit on Mindanao, primary forest is doomed in the short term and secondary forest in the near future. With an exploding population and a government not interested in environmental controls or conservation, the forest will of necessity be converted into farmland or banana and palm-oil plantations.

The near-perpendicular ridges and slopes of Mount Kitanglad resist farming and harbor the breeding pair of Philippine Eagles we see. Other populations live in remote areas, most too rugged to inventory, on the islands of Luzon, Samar, and Leyte. The Philippine Eagle Foundation estimates that enough habitat exists for at most 200 pairs in the mountainous regions of Mindanao and another 200 pairs in the rest of the archipelago.

As the finale of our trip, we visit the Philippine Eagle Foundation in Davao, largest city on Mindanao. As part of the yearlong research for his art exhibit, David has conferred with the foundation and arranged for us to meet the staff and tour the grounds. Executive director Dennis Salvador has been with the foundation since it began. We sit in his office and dodge Glossy Swiftlets that dart though the open window to get to their nests in the hall.

We cross the bridge into a wooded compound and see more birds foraging in the trees than kept in cages. A Blue-throated Bee-eater and Hooded Pitta temporarily distract us from a tethered Brahminy Kite sitting on a limb a few feet above the path. It poses for us unperturbed.

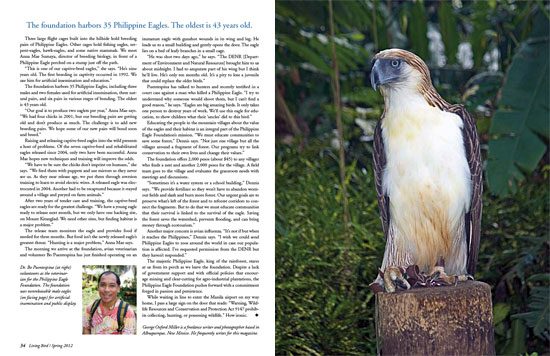

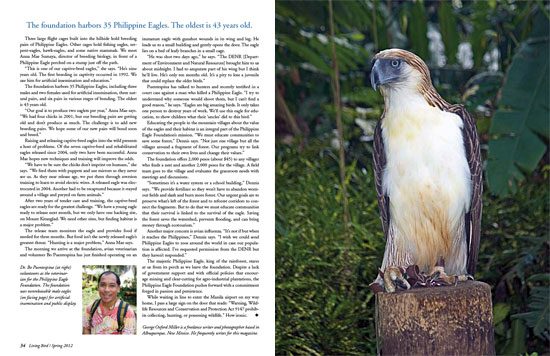

Three large flight cages built into the hillside hold breeding pairs of Philippine Eagles. Other cages hold fishing eagles, serpent- eagles, hawk-eagles, and some native mammals. We meet Anna Mae Sumaya, director of breeding biology, in front of a Philippine Eagle perched on a stump just off the path.

“This is one of our captive-bred eagles,” she says. “He’s nine years old. The first breeding in captivity occurred in 1992. We use him for artificial insemination and education.”

The foundation harbors 35 Philippine Eagles, including three males and two females used for artificial insemination, three natural pairs, and six pairs in various stages of bonding. The oldest is 43 years old.

“Our goal is to produce two eaglets per year,” Anna Mae says. “We had four chicks in 2001, but our breeding pairs are getting old and don’t produce as much. The challenge is to add new breeding pairs. We hope some of our new pairs will bond soon and breed.”

Raising and releasing captive-bred eagles into the wild presents a host of problems. Of the seven captive-bred and rehabilitated eagles released since 2004, only two have been successful. Anna Mae hopes new techniques and training will improve the odds.

“We have to be sure the chicks don’t imprint on humans,” she says. “We feed them with puppets and use mirrors so they never see us. As they near release age, we put them through aversion training to learn to avoid electric wires. A released eagle was electrocuted in 2004. Another had to be recaptured because it stayed around a village and preyed on farm animals.”

After two years of tender care and training, the captive-bred eagles are ready for the greatest challenge. “We have a young eagle ready to release next month, but we only have one hacking site, on Mount Kitanglad. We need other sites, but finding habitat is a major problem.”

The release team monitors the eagle and provides food if needed for three months. But food isn’t the newly released eagle’s greatest threat. “Hunting is a major problem,” Anna Mae says. The morning we arrive at the foundation, avian veterinarian and volunteer Bo Puentespina has just finished operating on an immature eagle with gunshot wounds in its wing and leg. He leads us to a small building and gently opens the door. The eagle lies on a bed of leafy branches in a small cage.

“He was shot two days ago,” he says. “The DENR [Department of Environment and Natural Resources] brought him to us about midnight. I had to amputate part of his wing but I think he’ll live. He’s only ten months old. It’s a pity to lose a juvenile that could replace the older birds.”

Puentespina has talked to hunters and recently testified in a court case against a man who killed a Philippine Eagle. “I try to understand why someone would shoot them, but I can’t find a good reason,” he says. “Eagles are big amazing birds. It only takes one person to destroy years of work. We’ll use this eagle for education, to show children what their ‘uncles’ did to this bird.”

Educating the people in the mountain villages about the value of the eagles and their habitat is an integral part of the Philippine Eagle Foundation’s mission. “We must educate communities to save some forest,” Dennis says. “Not just one village but all the villages around a fragment of forest. Our programs try to link conservation to their own lives and change their values.”

The foundation offers 2,000 pesos (about $45) to any villager who finds a nest and another 2,000 pesos for the village. A field team goes to the village and evaluates the grassroots needs with meetings and discussions.

“Sometimes it’s a water system or a school building,” Dennis says. “We provide fertilizer so they won’t have to abandon worn-out fields and slash and burn more forest. Our urgent goals are to preserve what’s left of the forest and to reforest corridors to connect the fragments. But to do that we must educate communities that their survival is linked to the survival of the eagle. Saving the forest saves the watershed, prevents flooding, and can bring money through ecotourism.”

Another major concern is avian influenza. “It’s not if but when it reaches the Philippines,” Dennis says. “I wish we could send Philippine Eagles to zoos around the world in case our population is affected. I’ve requested permission from the DENR but they haven’t responded.”

The majestic Philippine Eagle, king of the rainforest, stares at us from its perch as we leave the foundation. Despite a lack of government support and with official policies that encourage mining and clear-cutting for agro-industrial plantations, the Philippine Eagle Foundation pushes forward with a commitment forged in passion and persistence.

While waiting in line to enter the Manila airport on my way home, I pass a large sign on the door that reads: “Warning, Wildlife Resources and Conservation and Protection Act 9147 prohibits collecting, hunting, or possessing wildlife.” How ironic.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you